“I was at the Hard Rock Café in Tampa, Florida,” recollects Metal Blade Records founder, Brian Slagel, “and there was this really weird-looking guitar on the wall, with this really strange paint job, really crazy colours and it said that Kerry King had played it. I thought, ‘There’s no way Kerry ever played this thing!’ So I took a picture of it and texted it to him. His response summed everything up. He just said, ‘The 90s were weird…’”

Whichever way you slice it, the 90s were a turbulent time for heavy music. Thanks to mainstream metal’s global dominance during the 80s and the birth and blossoming of thrash and the metal underground, things could hardly have seemed healthier as the 90s dawned.

The decade began with the release of Megadeth’s Rust In Peace, Slayer’s Seasons In The Abyss and Kreator’s Extreme Aggression: all arguable high watermarks for thrash. Meanwhile, an unrelenting stream of classic albums kept the death metal scene vibrant and defiantly extreme.

As the years passed, however, that stream slowed to a trickle as both thrash and death metal succumbed to the law of diminishing returns. For the thrash scene in particular, the arrival of grunge, combined with Metallica’s radio-friendly upgrade for 1991’s Black Album, resulted in a lot of bewildered flailing around from previously reliable bands.

“Grunge started kicking everyone’s ass and a lot of bands were worried,” Brian Slagel remembers. “They were thinking, ‘What are we gonna do? Where can we go?’ A lot of people thought that metal was dead and over with at that point. Eventually, as we all know, there was a huge renaissance, but that period was definitely a downturn for all kinds of metal and there really wasn’t much going on at all.”

Whether it was Kreator’s dalliance with industrial-tinged alt-rock on 1992’s Renewal or Exodus’s misjudged shuffle into groove metal territory for the same year’s Force Of Habit, thrash underwent a public identity crisis as the 90s progressed. Death metal was heading for the buffers, too: the rise of grunge, the first rumblings of nu metal and black metal’s media-baiting notoriety all conspired to make the genre’s unpretentious take on musical hostility look and sound like yesterday’s news.

“In the late 80s and early 90s, the underground felt important,” says Karl Willetts, Memoriam frontman and ex-Bolt Thrower alumnus. “Bolt Thrower were really pro-active, doing loads of touring and making records. It was a real peak of creativity and everyone around us seemed to be in the same place. Then we got to the mid-90s and death metal just seemed to hit a wall.

"The next generation were listening to grunge instead of extreme metal. I was distracted by it myself, by bands like Soundgarden, and it took me on a different path, away from extreme music. That’s partly why I left Bolt Thrower in ’94.

"But alongside that, there were crossovers into rap, the Judgment Night soundtrack and so on, and then black metal happened. All of these things diluted what the scene was about and distracted people towards other avenues and different ways of doing things. Suddenly the scene didn’t belong to us anymore.”

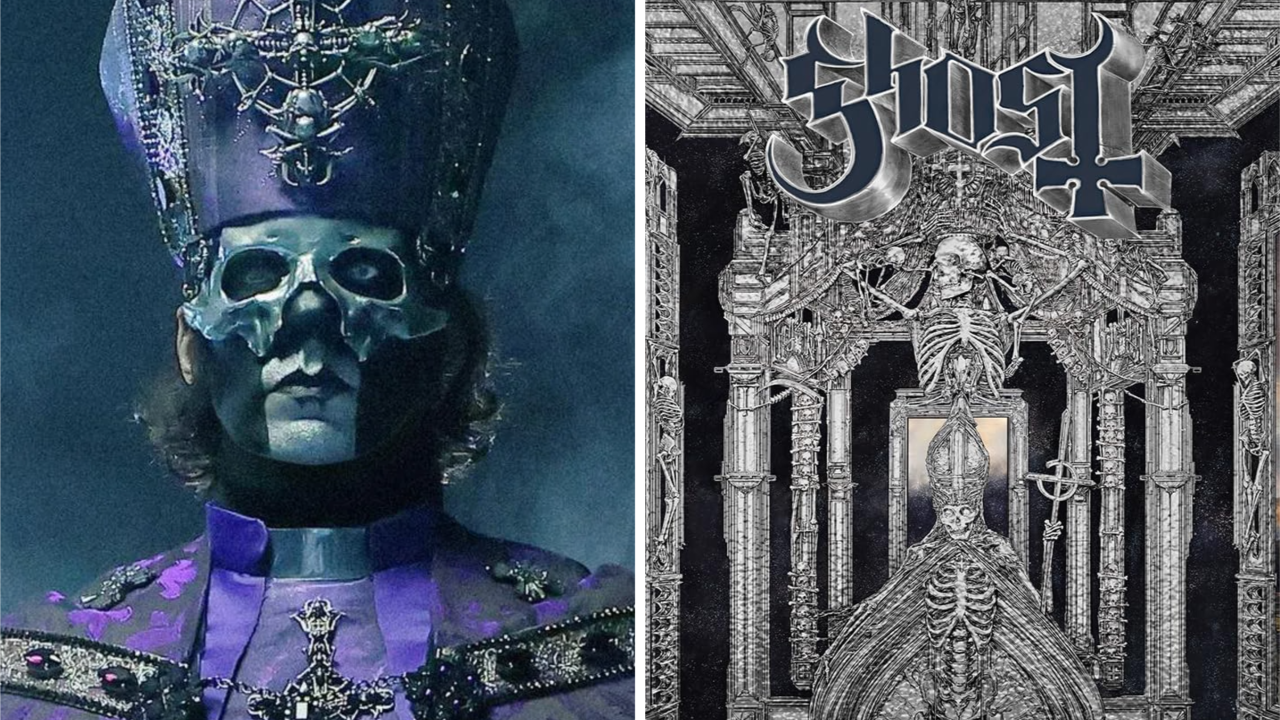

Black metal’s impact on the underground in the 90s was undeniably huge. While death metal bands turned up wearing band shirts and baggy shorts, generally with no specific philosophical agenda to propagate, the (primarily Norwegian) black metal scene offered a visually and conceptually startling alternative that dominated column inches and simply seemed more exciting to kids with a taste for the extreme.

“The black metal thing had a massive impact on me,” Karl sighs. “I hated it. It was all about image, trying to look evil, burning down churches, right-wing ideology… the complete polar opposite to where I was coming from.

"But it was another generation of people coming along and forging their own identity, something that was theirs and not mine. That’s why I didn’t like it. I understand it now. That’s the simple reason why there was a dip in the mid-to-late 90s: things change.”

It’s not just musical tastes and subcultural tropes that wrenched the rug from under extreme metal’s feet in the 90s. Karl suggests that a lack of political fury also contributed to thrash and death metal’s deterioration, as the lack of a common philosophy undermined the unity of old.

“The socio-political aspect is really important,” says Karl. “It was really strong in the late 80s, the end of the Thatcher era and the nuclear threat, and that’s where we came from, that political punk influence.

"But years of conservatism and global capitalism filtered all that out and somehow it depoliticised people. We lost that angle in the music. When people get into music and there’s a political dimension, there’s a lot of passion involved, and that was lacking as the 90s progressed.”

The underground’s state of flux continued until the fag-end of the decade, at which point there was a very noticeable and welcome sea-change in fortunes, particularly for death metal.

Albums like Gorguts’ Obscura and Nile’s Amongst The Catacombs Of Nephren-Ka (both 1998) and Cryptopsy’s …And Then You’ll Beg (2000) breathed new life into an ailing scene, while the death metal influence in revolutionary records like The Dillinger Escape Plan’s Calculating Infinity and Slipknot’s globe-battering eponymous debut (both 1999) was more than apparent to anyone who had spent the early 90s listening to Deicide and Suffocation.

Even Napalm Death, who had spent part of the 90s in a state of cross-pollinated, alt-rock confusion, made a resolute return to flat-out, ultra-intense grindcore for 2000’s Enemy Of The Music Business and have barely paused for breath since.

Meanwhile, thrash was given a ferocious, rejuvenating kick up the arse via The Haunted’s self-titled debut album in 1998 and has been motoring along nicely ever since, not least due to the mid-00s old-school thrash revival that brought us Municipal Waste.

It is arguably due to the dogged, non-careerist nature of most extreme metal musicians that both thrash and death metal survived the 90s at all. As far as Brian Slagel is concerned, getting through metal’s weirdest decade was a straightforward matter of keeping the faith and not being distracted by transient trends.

“I guess I’m just stubborn!” he laughs. “For instance, I’m very proud to say that we’ve never signed any nu metal bands, ha ha ha! We also had some of our biggest success in the 90s, with Six Feet Under, for example, but it was definitely a difficult time for everybody and I did feel, when it got towards 1998 and 1999, that stuff was starting to happen again.

"New bands were coming out and a scene was starting to happen and I felt pretty excited going into the new decade. Surviving the 90s was good, but there was an upswing of stuff happening right after that.”

“In a way it all went full circle,” concludes Karl. “There’s been a big renaissance for death metal and all kind of underground music and it hasn’t stopped since the early 2000s, which is when I re-joined Bolt Thrower… so it’s all down to me, ha ha!

"The thing is, the underground is such a wide-ranging global thing that there’s room for everything now. That’s what’s given it its longevity. I can’t imagine a time in the future where there’ll be no such thing as extreme metal. Not in my lifetime anyway!”