How The Beatles became the first band to make a stand for civil rights

In 1964, faced with playing segregated audiences in the southern United States, The Beatles took a stand

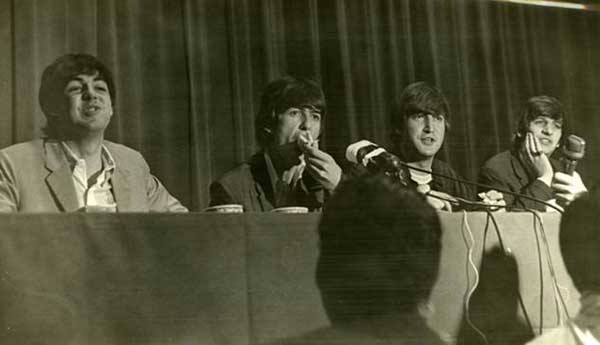

In 1964, pop groups in America didn't talk about politics or social issues. When they spoke to the press at all, it was about very superficial, Tiger Beat-style topics such as what they like to do in their dressing room before a show or whether they had favourite pets at home.

When The Beatles arrived on the scene in 1964, they changed all that. Their invasion of America was not just about music and fashion, but reshaping the very idea of a pop star into a thinking, feeling, three-dimensional human being with principles and opinions.

And all four Beatles were united in their opinion on the policies of racial segregation that were in practice through much of the southern United States. So much so that in the midst of their 23-city tour, they issued a brief, forceful press statement that said: “We will not appear unless Negroes are allowed to sit anywhere.” The Fabs were looking ahead to a date at the Gator Bowl Stadium in Jacksonville, FL, where they'd heard that blacks were confined to the upper tiers at public events.

In response, The Florida Times-Union, Jacksonville's paper, ran a disparaging editorial entitled “Beatlemania Is A Mark Of A Frenetic Era.” The group was called “a passing fad” and “hirsute scourges of Liverpool.” The underlying tone was basically “How dare these moptop Brits weigh in on matters of race."

John Lennon answered by saying, “We never play to segregated audiences. I'd sooner lose our appearance money.”

Though US President Johnson had signed the Civil Rights Act, banning discrimination “on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex, or national origin,” racial tensions ran high in 1964. Protests, riots and violence were happening everywhere, in northern and southern cities, Jacksonville included.

But two Jacksonville residents who attended The Beatles concert on September 11th say that the atmosphere was all about music and excitement.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Don Walton, then a 16-year old fan who was front row centre at the show, told me, “There were some problems in our city, but we were never hardcore like Mississippi or South Carolina. I know there were black kids at The Beatles' show. It was an open air concert too, which might've made it easier to have an integrated concert. With the size of the Gator Bowl, I don't think the authorities were worried about the small percentage that might’ve been interested that were black.”

Kitty Oliver was one of those black teenagers. “Where I sat, there were two other black kids,” she told me. “I ran into them accidentally as I found my seat. I went alone. No school friends would go. I remember that I sat in the high-up least expensive seats, because that is all my family could afford. It was scary in the sense that I didn't know what to expect.

"You develop a strong antenna for danger, watchful of any sudden movements or shift of mood in a crowd, and, at the same time, a shield that allows you to look straight ahead and seem impervious to the outside.”

Opening the show were The Exciters, a black R&B vocal quartet from New York, best known for their hit Tell Him. Though WAPE, the local radio station promoting the concert, chose the support act, The Beatles were most likely pleased. “I don’t think people connected The Beatles with their love of R & B, the way we all do now,” says Walton.

Once the Beatles started to play, Oliver forgot about any possible danger. “There were a lot of girls screaming, and I was screaming too,” she laughed. “And singing all the lyrics to the songs. I loved the Beatles, and had seen Hard Day’s Night seven times. I even won one of those short '___ is my favourite Beatle' contests and my name was called on the radio announcing that I had won a free signed album. I kept it for decades.”

In their 12-song set list, four were covers, originally by black artists – Long Tall Sally, Boys, Twist and Shout and Roll Over Beethoven. At all of the press conferences they did on the ‘64 tour, they were equally vocal about their reverence for black artists. When asked what they enjoyed listening to, they regularly answered, "American soul music, Marvin Gaye, The Miracles . . ." And later the same year, they invited Mary Wells to join them for a UK tour.

Smokey Robinson said, “The Beatles were the first white artists to ever admit that they grew up and honed themselves on black music.”

The Beatles’ human rights crusading would continue until the group’s end (if there was ever a true Fifth Beatle, it was keyboardist Billy Preston), and right on through their solo careers. Paul McCartney summed up their position when he told a reporter in 1966, "We weren't into prejudice. We were always very keen on mixed-race audiences. With that being our attitude, shared by all the group, we never wanted to play South Africa or any places where blacks would be separated. We just thought, 'Why should you separate black people from white? That's stupid, isn't it?'"

Bill DeMain is a correspondent for BBC Glasgow, a regular contributor to MOJO, Classic Rock and Mental Floss, and the author of six books, including the best-selling Sgt. Pepper At 50. He is also an acclaimed musician and songwriter who's written for artists including Marshall Crenshaw, Teddy Thompson and Kim Richey. His songs have appeared in TV shows such as Private Practice and Sons of Anarchy. In 2013, he started Walkin' Nashville, a music history tour that's been the #1 rated activity on Trip Advisor. An avid bird-watcher, he also makes bird cards and prints.