November 1970. Sunset Sound, 6650 Sunset Boulevard. Jim Morrison, Robby Krieger, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, engineer Bruce Botnick and producer Paul A. Rothchild are staggering through rehearsals for The Doors’ sixth studio recording. Even though they are back where The Doors made their first two albums, the mood is deadly.

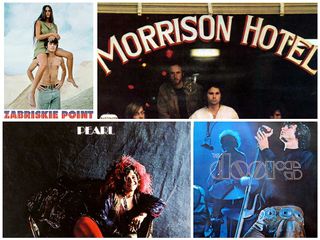

The band have busked through a meagre collection of material, including the germ of L.A. Woman, basic chords for Riders On The Storm, some blues jams and a couple of discards, namely the demo for Hyacinth House, and one track they’ve already finished. Tentatively called Latin America, it’s been offered up for Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Zabriskie Point. The director rejected the song after The Doors played it live for him.

“We played it so loud we blew his ears out,” says Doors drummer John Densmore.

Equally unimpressed, Rothchild slumps over the console.

“You know what? I can’t do this anymore. This isn’t working. This music is like cocktail jazz. It’s awful. You produce it. I can’t”.

Bombshell dropped, Rothchild sweeps up his belongings, including a bag of grass he calls his ‘Killer Destroyer’ stash, gives everyone a brief hug, and exits to stunned silence.

Ray Manzarek recalls the day. “We were giving Paul a preview and he was bored. We played the songs very badly – with Jim – but there was no chi, no energy. We didn’t want to be back in Sunset, and Paul couldn’t bring us back to life. In that instant he was right. As soon as he left the room, that’s when L.A. Woman started.”

Rothchild’s lethargy was understandable. The Elektra Records soundman had fallen out with label boss Jac Holzman and gone freelance. The Doors felt like old ground. He’d spent a fractious time in 1970 producing Morrison Hotel and then sifted through hours of stage tapes for Absolutely Live. He’d also endured the trauma of producing Janis Joplin’s Pearl album. Joplin died before its completion – aged 27, like Brian Jones. Carousing with Jim one night the singer had mumbled, “Brian, Janis, Jimi – you’re drinkin’ with number four”. It was the last straw.

By 1970, the people prepared to buy Morrison’s antics, and those who weren’t, were divided into two camps. Paul Rothchild was now in the latter group.

“Morrison looked ugly,” he said. “He was unhappy with his role as a national sex symbol , and after the Miami obscenity trial [August 1970] he did everything in his power to obliterate that, He gained enormous weight, he grew a beard. I quit because I’d grown tired of dragging The Doors from one album to another, especially an unwilling Jim, and he had virtually dried up. Two out of three times, Jim would either not want to work, or would go into the studio drunk. He would intentionally disrupt things… never fruitfully. Most of my energies were spent trying to co-ordinate Jim with the group.”

Doors manager Bill Siddons, who was virtually inured to Morrison’s excesses with booze, cocaine, no-shows, hangers on and the endless liabilities of the band’s live act before, during and after Miami, remembered one afternoon “when Jim came into rehearsals and drank 36 beers”.

Ever loyal to an old friend, even Manzarek agrees – the situation was dire.

“Jim was an alcoholic. A genetic predisposition to alcoholism ran in his family. It was hard to tell him to clean up his act. One day, around the Morrison Hotel sessions, John and Robby sat him down at Robby’s dad’s house by the pool, and told him, ‘This is seriously affecting us all now as a group, and you physically’.

"Jim says, ‘I know. I drink too much and I’m trying to quit’. Which was a rare admission. We told him we’d help. Jim said, ‘Thanks. Now let’s go get some lunch at the Lucky-U. I want some funky Mexican food and a drink’. That was Morrison. The romantic poet who wrote ‘I woke up this morning, got myself a beer’. A real ‘Fuck you!’ line. Unfortunately, that was the reality. Jim’s attitude was always, ‘Look out man, I’m hell bent on destruction’.

"We couldn’t moralise. We figured he might emerge from the spiral, but working with Jim in the studio was the only way we knew how to transcend his problem.”

After Rothchild’s departure The Doors went to the Moo-Ling restaurant and considered their options. Sunset was out; likewise a return to Elektra’s own studio. Krieger offered to produce but Morrison had a plan. “Why don’t we just do it in our rehearsal room, in The Doors office? We like it there. Bruce – you produce it with the guys. You know how I work,” he smiled. Once Holzman agreed to the idea, Botnick transformed The Doors Workshop at 8512 Santa Monica Boulevard on the corner of La Cienega into a makeshift studio.

The squat two-storey building was near a variety of cheap motels, strip joints, liquor stores and burlesque bars – Morrison’s kinda town. The room was a mess. Morrison’s desk was covered in bottles of tequila and bourbon while an ashtray with a peeling tartan design overflowed with discarded joints and cigar butts. Botnick hauled the old eight-track board The Doors used on Strange Days across the street from Elektra and set up his brand new console on the first floor with an intercom microphone over his head to communicate with the band, out of sight downstairs.

“It was like home from home,” Botnick says. “ There was a pinball table and paintings on the wall. One was of a nude with a hole cut out of her head. I hung packing blankets and towels up for baffling and wired up the remote. It was primitive.”

John Densmore didn’t mind.

“I used the same drum kit I had on the first record,” he says. “It was like going back to the metaphorical garage in Venice where we started. I told Ray, I wanted to get the feeling Miles Davis had on Live At Carnegie Hall, where you could make a mistake, but you went for passion.”

Speaking from his office in Sherman Oaks, Bill Siddons recalls the sessions: “I’d rented the Workshop, and built the studio wall so they could rehearse. Bruce used my office as his studio. The board was on my desk. Mostly I worked there in the day and they came in at night. I didn’t hang around. The record works because they focused on each other. They couldn’t see the producer. It was different. Using the clubhouse was a masterstroke. They made the album from their heart.”

Morrison was fairly straight during the early days of recording, at least by his extraordinary standards.

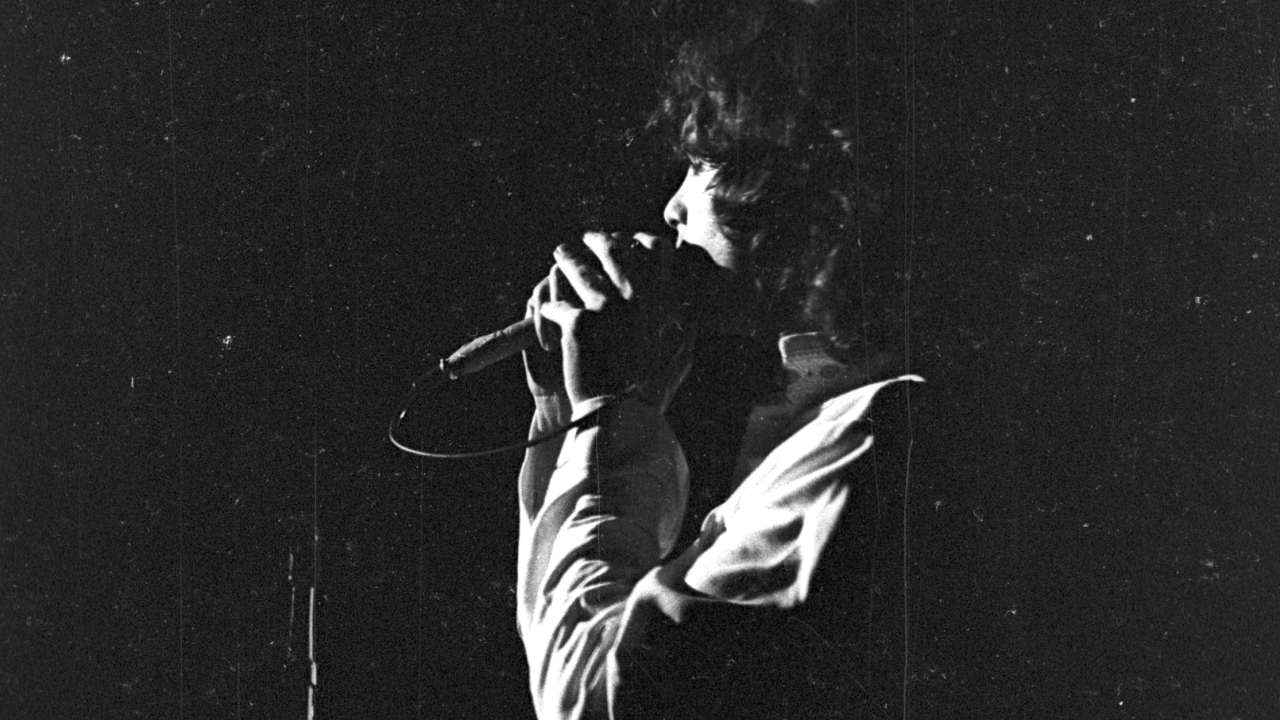

Botnick: “He was punctual, professional, all those boring things.” According to Botnick, “some sessions even began in the afternoon! The Doors were making the record Jim wanted, rather than what was expected. His notion of The Doors was as a blues band, and not a pop group”. Hanging off his stage mic, a gold Electrovoice- 676-G, Morrison sang in front of a tile on which he’d written ‘A clean slate is an empty slate’; a possible jibe at Rothchild. For certain songs he crouched in the doorway of the toilet, having ripped the door off for good measure. He was in the mood.

As Densmore says, “If he kept his alcoholism out of the studio everything worked great. He was in trouble, yeah, he was, but without the world around him, everything else went away.”

For the most part Morrison knuckled down. The bulk of recording was completed in six days. The other Doors knew the singer wasn’t likely to endure the months Morrison Hotel had taken. During recording he gave an interview to the Village Voice, describing this rapid process. “This new album, it went really quick. Like a song a day, which is unusual. Like the first album. Amazing. Partly because we went back to the original instrumentation: just the four of us and a bass player.” With most of the basics finished, Morrison said he was ready for more down time. “I don’t read or write much. I don’t do much of anything. But I will get back in the saddle. I’ve just been kind of lazy. I go through cycles of non- productiveness, and then intense periods of creativity.”

The interviewer mentioned Morrison’s weight gain. “Why is it so onerous to be fat? Fat is beautiful,” the singer replied. “I feel great when I’m fat, I feel like a tank, y’know? I feel like a large mammal, a big beast. When I move through the corridors or across the lawn, I just feel like I could knock anybody out of my way. It’s terrible to be thin and wispy – you could get knocked over by a strong wind.”

Fuelled on a succession of screwdrivers, Morrison outlined what it took to gain entrance to his circle: “You gotta get smashed and make a fool of yourself in a public place. You gotta get eighty-sixed [barred] from seven nightclubs. That’s the Irish thing. I hang around mostly with the Irish – and the Italians.” And then he challenged the reporter to a bout of arm wrestling.

He was less flippant with the Los Angeles Free Press. Explaining the new recording approach, Morrison let slip “we do a lot better when we’re rehearsing. We leave a tape running. It’s a lot cheaper and faster that way. Not that the other producer [Rothchild] was a bad influence… but we’ll be ourselves for better or worse, co-producing with Botnick.”

At the end of the interview Morrison gave his then definitive attitude towards narcotics. “There seem to be a lot of people shooting smack and speed now. Alcohol and heroin and downers – these are painkillers. Alcohol for me, cause it’s traditional. Also, I hate scoring. I hate the kind of sleazy sexual connotations of scoring from people, so I never do that. I like alcohol; you can go down to any corner store or bar and it’s right across the table.”

By the end of November, five of L.A. Woman’s 10 songs were near completion. The opening song The Changeling was plucked from one of Morrison’s 1968 notebooks. A classic rocker à la Roadhouse Blues, The Changeling contained the mantra ‘I had money, I had none’, summing up Morrison’s attitude to life. An obvious single, said the band.

Robby arrived with Love Her Madly, one of his ‘girl’s-driving-me-nuts’ numbers. At Jac Holzman’s insistence, it became the album’s lead-off single, released a week before Morrison departed for Paris on March 1971. Krieger pleaded for Riders On The Storm but was overruled. The non-album B-side was a jokey blues romp written by Willie Dixon called (You Need Meat) Don’t Go No Further. Sung by Manzarek, it epitomises the ‘hurried out-take’, with only an occasional grunt from Morrison.

Hyacinth House was a Doors collaboration, whipped into shape by Manzarek, although Morrison and Krieger came up with the basic track while tripping at Robby’s idyllic beachfront house in 1969, where they recorded a demo in the guitarist’s home studio, marvelling at the hyacinths growing round Krieger’s pool.

Latin America was renamed L’America. The original track was left intact, though Morrison overdubbed a guttural single word ‘fuck’ and Botnick phased Densmore’s drum break. Lyrically it was a slight piece concerning a short holiday Jim took in Mexico with his drinking crew. It was all about sex with prostitutes, marijuana and tequila – hence ‘I took a trip down to L’America, to trade some beads for a pint of Gold’.

The song poem The WASP (Texas Radio And The Big Beat) with its marching band rhythm and phased drum break was another adaptation from 1968 and had often been played live before recording took place. Usually, …Texas Radio… was used as the prelude to Peace Frog, from Morrison Hotel, or as part of a medley – a moment of hiatus between When The Music’s Over, Celebration Of The Lizard and The End. Jim was as proud of the lyric as anything he’d written and included the poem inside the 1968 tour programme.

According to Krieger, “The WASP… was about the new music Jim heard when his family were moving around the South West States in the 1960s. He got this vision of a huge radio tower spewing out noise… This was when Wolfman Jack was on XERB, out of Rosarito Beach, in Mexico, blasting out 250,000 watts of soul power. He saturated the airwaves – you could hear him from Tijuana to Tallahassie up to Chicago where Ray lived. There were no laws about how powerful a radio station could be. That started rock ’n’ roll for my generation.”

Morrison – the WASP, the White Anglo- Saxon Protestant in the song – had been a Wolfman fanatic.

“My adolescence coincided with rock ’n’ roll although I never went to any concerts,” he said. “In my head I heard a whole concert, with a band and singing and a large audience. I was taking notes at a fantastic rock concert that only existed inside my head.”

The Doors used a bass on every track, except L’America. Botnick hired the seasoned Jerry Scheff, who had just finished a stint with Elvis Presley at the International Hotel in Las Vegas. Morrison, a Presley fanatic, was delighted. So was drummer Densmore.

“Jerry was incredible; an in-the-pocket man. He allowed me to communicate rhythmically with Morrison, and he slowed Ray down, when his right hand on the keyboards got too darn fast.”

In December Botnick persuaded the Doors to hire young Texan Marc Benno as rhythm guitar foil to Krieger. Benno would play on four numbers.

“Morrison was a nice guy who was on a roll,” he said. “He reminded me of a wild gorilla at the sessions. He had a hand-held microphone and a telephone book full of songs. One day he stopped the session and took me to lunch. He ordered ox tails and drank Jack Daniel’s out of the bottle. When we got back Jim had me show Robby a lick I was playing, and we used it on L.A. Woman.

“From there, it was a jam right through the album. We worked the tunes up on the spot, and did very few takes. We never saw anyone but each other, which kept distractions to a minimum, and kept Jim from feeling inhibited, which I don’t think was a problem for him, anyway! He cut loose completely while recording, and the result was a very spontaneous album.”

In the second week of December the band held what they called “the blues day”. After knocking off John Lee Hooker’s Crawling King Snake, a regular in the repertoire in their 1967 club dates, Morrison delighted everyone with Been Down So Long, its title borrowed from Richard Farina’s similarly named novel. He set it inside a prison. The prospect of spending six months banged up in Florida’s Dade County Jail East Wing – a notorious ‘hell-hole in paradise’ – didn’t fill him with delight. Yet, that was where he would end up if the aftermath of the Miami trial went wrong. When he sang ‘Warden, warden, warden, won’t you throw away your lock and key?/Come along here mister, let the poor be’, he meant every word. Then there was Cars Hiss By My Window, with Morrison’s wah- wah guitar impersonation.

Manzarek: “Cars… was brand new; a week old maybe. Jim said it was about living in Venice [Beach], in a hot room, with a hot girlfriend, and an open window, and a bad time. It could have been about Pamela Courson.”

Certainly, the lines ‘Can’t hear my baby, though I call and call’ seemed to reference Pam, who was now living in Paris, hopelessly embroiled in heroin. On that blues roll, the song L.A. Woman completed the session. Lyrically, Morrison was inspired here by Los Angeles novelist John Rechy, whose 1963 novel City Of Night was a college favourite, and 1940s writer John Fante, who described Hollywood in love-hate lines like: ‘So fuck you, Los Angeles, fuck your palm trees, and your high-assed women, and your fancy streets… Los Angeles, give me some of you! Los Angeles come to me the way I came to you, my feet over your streets, you pretty town I loved you so much, you sad flower in the sand…’

Manzarek says: “L.A. Woman was recorded in a state of high excitement. The Doors jumped in. We dug our teeth into that song. It was all about passion and hauling ass. It felt like we were on Route 101, on the road from Bakersfield to San Francisco. You can hear our enthusiasm. Welcome to Los Angeles!”

On December 8 Morrison celebrated his 27th birthday at the Village Recorders studio in West LA, taping poetry for a solo album. He was tired and hitting the bottle. After imbibing a lot of Old Bushmills he passed out and collapsed onto a stack of equipment. Everyone laughed: Hey, that’s Jim for ya! The next day Morrison demanded the Doors hit the road to play L.A. Woman live. Dates in Dallas and New Orleans were arranged for the 11th and 12th.

Today rare bootlegs reveal that in Texas a doomy 15-minute version of the title track was unveiled alongside The Changeling, where Morrison sang in a falsetto scat he’d never used before. The Texas crowd also heard The WASP and Love Her Madly — Morrison changing the lyric to ‘Do you love her madly?’. Most surprising of all was a work in progress called Riders On The Storm, which Densmore describes now as “unlike anything we’d ever done”.

The Texas show at the Dallas State Fair Music Hall was relatively triumphant. Morrison is drunk and sounds like he’s going through a private hell, but he is coherent. Stoned immaculate. But if Mr. Mojo was barely risin’ then, in Louisiana he didn’t get up at all. The gig at the Warehouse, New Orleans, was a fiasco. It was the last live show the band ever gave.

The music was over. Manzarek recalls: “He just lost his energy completely. He was so dissipated. His voice got lower and lower and he ground to a halt. He was empty. This wasn’t like when he comes to the studio wasted and can’t deliver, but then there’s always tomorrow – and by God he will deliver. This was final.”

Drummer Densmore agrees. “His life-force was gone. He was so out of it. That was a depressing experience.”

Doors road manager Vince Treanor looked on from the wings. “He was very drunk. They finished with Light My Fire and Jim was hanging on the microphone trying to sing. He sat on the drum platform and didn’t come back in for his vocal. Finally John kicked him and he got up and mumbled ‘Yeah… yeah…’ then he picked the mic up high and smashed the entire stand through the floor… Walked off stage and that was show over. John got up and said ‘Right, that’s it, I’m not playing anymore’, and he walked off leaving Ray and Robby there.”

With a tentative booking for four shows at Madison Square Garden in January cancelled, thanks to Jim’s Louisiana meltdown, as a mark of contrition he returned to the studio the next week to finish Riders On The Storm. After looking at the lyric, Bruce Botnick played him the old Stan Jones pop song Ghost Riders In The Sky. Yet Morrison already had the key line, which he’d nicked from poet Hart Crane, who had written of ‘Delicate riders of the storm’ in his work Praise For An Urn. No one knew then but Riders On The Storm was Jim Morrison penning his own epitaph.

According to Manzarek: “He adapted the song from his script for the movie HWY. It was about a hitchhiker, a killer who hijacks a blue Mustang in Joshua Tree desert. Jim was obsessed with HWY, which he made with a bunch of his UCLA cronies.” Footage from the project was used in the Doors documentary, When You’re Strange.

“Never finished it. Great photography though from Paul Ferrara,” says Manzarek. “After 10 minutes of coherent shooting the four of them got totally wasted on Cannabinol, a heavy pill version of marijuana. Paul told me they lost it afterwards and tripped back to Los Angeles. Anyhow, it gave Morrison the lyric for the last song he ever sang on planet Earth with The Doors. An insane killer, a lunatic, he’s going to do something bad. Give him a ride, why don’t you? But when the end comes you realise Jim’s singing a beautiful, romantic song: ‘Girl you gotta love your man/Take him by the hand/Make him understand/The world on you depends/Our life will never end…’ He was singing that for Pam.”

In January, during the hottest temperatures ever recorded in that month in California, The Doors and Botnick moved into Poppi Studios, Motown’s West Coast complex, to mix the album. Morrison added a harmony vocal to Hyacinth House and, having suggested to Botnick that they use a thunderstorm sound effect as an opener for Riders On The Storm, he climaxed the final number with an eerie vocal whisper that was his last recorded contribution to the band. Elektra boss Jac Holzman turned up during the final mixing. On hearing the album he broke down in tears. His most beloved charges had delivered after all. Now they were out of contract. Elektra’s gold standard group, the biggest band in America, owed him no more.

With L.A. Woman finished and the title agreed, The Doors convened for the cover photo shoot. Morrison sat down on a stool, hunched, an unseen bottle of Irish whiskey at his feet.

Manzarek: “In that photo you can see the impending demise of Jim Morrison. He was sitting down because he was drunk. A psychic would have known that guy is on the way out. There was a great weight on him. He wasn’t the youthful poet I met on the beach at Venice.”

The album’s art designers, Wendell Hamick and Carl Cossick, were outside the Elektra family that oversaw previous Doors products. They came up with an idea for a rounded corner cover and a cellophane window. Behind that was a yellow inner sleeve showing a woman crucified on an electricity pole.

The album was released in April 1971. It hit the Top 10 a few weeks later. During the making of L.A. Woman, Morrison’s partner Pamela Courson went to Paris and stayed with Count Jean de Breteuil, a wealthy socialite with a penchant for blondes, violence against women and horrendous heroin abuse. Breteuil met Courson in Morocco when she was buying clothes for her boutique, Themis, on North La Cienega. Jim paid for Themis with his Strange Days royalty cheque. He wanted to call it ‘Fucking Great’.

Though he posed, awkwardly, wearing Pam’s flamboyant garb, Morrison detested the people who hung out with his girl. In the song Love Street he sang ‘She has robes and she has monkeys, lazy, diamond-studded flunkeys’. The original rhyme was ‘junkies’. Pam, a junkie herself, returned to Jim for a tempestuous Christmas then went back to Paris to renew her relationship with the Count on February 14.

Morrison was now talking about moving to France himself. He’d tired of being a rock star and wanted to escape. His attorney, Max Fink, warned Morrison that if Miami turned nasty he’d have his passport confiscated. A tactical exit from the USA was a good idea. While Courson was strung out on the Left Bank, Morrison started taking more cocaine. He chain smoked Marlboros and Gauloises, and became more addicted to hard liquor. He hung out with fellow Southerner Steven Stills at the Crosby, Stills & Nash house on Shady Oaks.

He and Stills shared a Florida military brat background. Jim’s father had served in the US Navy aboard a warship in the Gulf of Tonkin. Stills’ old man wasn’t far away. Jac Holzman saw Jim for the last time at an Elektra Records party to show off a new studio complex on March 3.

“He was unusually quiet. I could feel finality hanging in the air.” The party retired to the Blue Boar restaurant. “Jim was half there, half somewhere else,” Holzman recalled. “As we left, we said our goodbyes to him. We’d enjoyed a lifetime together in the concentrated blazing arc of rock ’n’ roll. Jim and I hugged each other, and then he turned somewhat awkwardly and walked away.”

A few days later Paul Rothchild was at Elektra on business.

“I heard the door open and felt this large man entering. I didn’t recognise him. Then I was tapped on the shoulder, and I turned around and this large person who looked like Orson Welles’ younger son, said ‘Hi, Paul’. I said to myself ‘Holy fuck! This is Jim?’.”

On the eve of his flight to Paris, Jim drove to the airport with friends. He got so smashed he missed the plane, and travelled out the following day, flying TWA Ambassador Class.

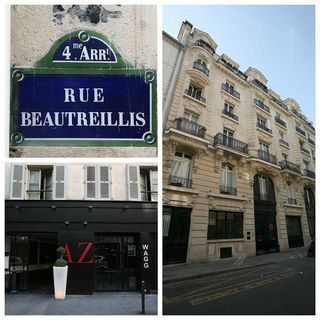

Reunited with Courson they moved into the fabulous Hotel George V, which he said “looks like a red-plush whorehouse”. The couple then moved to L’Hotel, Rue des Beaux-Arts, a funkier establishment favoured by Mick Jagger. Courson found them a lavishly furnished third floor, three-bedroom apartment in the Marais district, 17 Beautreillis, owned by a French model and starlet Elizabeth Lariviere.

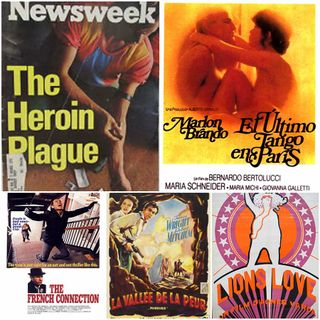

The week Morrison died, Newsweek ran a cover story – ‘The Heroin Plague’ – about the flood of heroin in Europe and America, much of it arriving via Paris and Marseille. At the same time, director William Friedkin was finishing his smack movie The French Connection. It was no secret that Paris was awash with heroin, nowhere more so than in the rock clubs.

A 21-year-old war photographer called Patrick Chauvel was working as a part-time barman at one such venue – the Rock ’n’ Roll Circus, on the Left Bank.

“I saw Jim Morrison many times at the club. He was rarely on his own,” he says today from his home in Paris. “He’d come in and sit on a couch, separate to the other clientele. He didn’t dance or make a big noise. I remember him coming in once three nights in a row. He came often, and there were times when I didn’t see him, but it was a big club on two floors, full of French stars – he wasn’t the only big star in the club.

"He was interested in my friend Sky, a half-breed American Apache. They had things in common: [they both spoke English], Sky’s dad was Scottish, the Vietnam War – Sky was a deserter – and the Indians. Sky said Jim was writing a poem about him, about the fact Sky’s father died in a car crash leaving the family to go back to the reservation in Tucson, Arizona. Jim wanted to replace Sky in Vietnam so he could get an honorable discharge. He was fascinated by the Indian’s story.”

Chauvel doesn’t believe Morrison was in the club to buy drugs.

“He didn’t need to buy in there. I never saw him take drugs, but he was always alcoholised, heavy on his words, a bit emotional. He’d be silent then he’d get up and say something really loud. You could see in his eyes, he had something important he wanted to say with a lot of energy, but it wouldn’t get past his mouth. It went through his eyes for a moment. That was it. He was fed up. He was not in a good place.”

Chauvel recalls seeing Morrison at the Circus with a blonde girl, not red-headed Pamela.

“There were other girls at his table who’d gather round him but he came in with this blonde often. They took photos, always Jim on the couch, in the same space.” [The nightclub manager, Sam Bernett, thinks the blonde may have been French-Canadian – which would make Robin Wertle, Jim and Pam’s 19-year old assistant, a good bet].

As for the narcotics scene, Chauvel equates it with the times.

“A lot of drugs, yes, a very free time for sex, a lot of jealousy and tension. The night club scene was heavy – gangsters and very bad cops. There were a lot of fistfights inside, which wound up on the stairs and in the street. There was a gunfight outside the club. I used to carry a bayonet for protection. Crazy but necessary. There was a triangle of these places – the Circus/Alcazar, La Bulle and Le Sherwood – big places in the same area. All heavy.”

Morrison lived a dual life: poet by day, obliterated by night. Moving to Paris hadn’t liberated him. For two weeks Pam and Jim shared the apartment before Lariviere split for St. Tropez with boyfriend Philip Dalecky, a drinking buddy of Jim’s. Morrison’s health was poor. He was suffering lingering pneumonia. He became asthmatic. He was prone to violent hiccups.

To escape the Parisian damp, the two young Americans decided to catch some sunshine. In April they travelled to Toulouse, visiting Andorra, Madrid, Granada and Morocco, where Jim had enjoyed the July climate a year earlier with Doors publicist Leon Barnard. On their return, May 3, Morrison seemed happy. He’d lost weight and regained strength. He and Pam enjoyed being tourists, shooting Super-8 home movies. That mood didn’t last long. Jim was often alone in the apartment now since Pam and the Count were, allegedly, seeing a lot of each other.

True to form, Jim looked for new buddies. He still frequented the Rock’n’Roll Circus and L’Alcazar, semi-exclusive dives by the Seine, patronised by the Stones, Hendrix, Led Zeppelin and whichever rocker was in town. Largely unnoticed, Morrison would prop up the bar – a bottle of vodka in tow.

Club manager Sam Bernett claimed, “Every time Morrison came in he was high, or drunk; in an abnormal state”.

Here on May 7 a young Frenchman called Gilles Yepremian came across Morrison being evicted from the Circus by the bouncers, after he sunk too much whiskey and rearranged the furrniture.

“He was totally drunk. Nobody recognized him,” says Gilles. “I got a taxi and we drove down the Seine. At the lights, Jim saw some policemen and he rolled down the window and shouted, ‘Fuck the pigs!’, so the driver kicked us out. I got another taxi and Jim was so pleased he tried to tip the man hundreds of francs. He was laughing uncontrollably. I didn’t know where he lived, so I took him to the apartment of my friend Hervé Muller.”

Muller and his girlfriend Yvonne Fuka opened the door to find Morrison lurching in his face.

“Hervé! Meet Jim Morrison. He’ll have to stay with you”. Morrison fell on Muller’s bed. They left him, passed out. The following afternoon Morrison took his new pals to the bar Alexander where he downed Bloody Marys and an entire bottle of Chivas Regal. He insulted nearby diners and became increasingly abusive. Gilles: “When he was sober he just looked like an American student on holiday. Very quiet and shy. Once he became drunk he was a madman.”

In May, Morrison and Pamela had dinner chez Muller.

“Play a record if you want,” young Hervé told Morrison. Jim settled on Buffy Sainte-Marie. Later he and Pam were so taken with the Corsican wine Fuka served they said, “Let’s go there!” They travelled to Marseilles again, where Morrison lost his passport and wallet. They waited two days for a replacement passport then flew to Ajaccio. On return they stayed at L’Hotel briefly before moving back to the apartment. Pam hired them 19-year old French-Canadian Robin Wertle.

“Neither Jim nor Pamela spoke French,” said Wertle. “My job included everything from getting a cleaning lady, typing letters, calling America,buying furniture, a typewriter for Jim, and making arrangements for him to show his films.”

He never did. Back in Paris, Morrison described his adventures to old friends Frank and Kathy Lisciandro, and suggested they visit: “There’s a room for you here”. He sent his attorney Max Fink a postcard of Moroccan scenes. “Dear Max, it’s a beautiful spring in the ‘City of Love’. Just got back from Spain, Morocco & Corsica – Napoleon’s birthplace. Take a vacation! The women are great & the food is gorgeous. Love, Jim x.” In late May, Morrison called John Densmore, expressing delight at his copy of L.A. Woman.

“He’d just got the finished album,” recalls Densmore. “Jim told me what a great place Paris was, and he said he was definitely coming back to LA. He didn’t know when. He said good things about the band… He sounded happier than when he left.”

Morrison resumed an acquaintanceship with Jacques Demy and his wife Agnes Varda, leading lights in the cinematic French New Wave.

“We had a common friend in Alain Ronay,” says Varda, who has seldom spoken in depth about Jim until now. “We saw The Doors in Los Angeles in 1967 when Jacques was filming The Model Shop,” recalls Varda from her Parisian home. “In 1970 he’d visited the set for my film Lions Love – he appears briefly.”

Alain Ronay was a student at the UCLA Film School in 1964; the older man was a post-graduate. Jim also turned up on set with Ronay for Demy’s film Peau D’Ane (Donkey Skin). During that initial visit to Paris, Morrison went to a birthday party for Varda’s 10-year-old daughter Rosalie.

“I think he liked us because we never asked him for anything,” says Agnes. “He was drunk that afternoon; drunk but happy. He drank a lot of brandy. Other times I saw him in my courtyard. He used to visit us and eat. He sat in my yard for many hours. Didn’t talk much. Didn’t like to gossip. I never even took his photograph. His wish in Paris was to write poems.

“I wasn’t like a private friend where he’d come and have dinner on his own. It was always in company. He sat in my kitchen in what’s supposed to be his time of craziness – he was OK. I didn’t bother him, and I wasn’t constantly bothered about him.”

In June, Jim and Pam flew to London, staying at the Hyde Park Hotel, which they hated. Pam resumed her liaison with the Count, who had the keys to Keith Richards’ and Anita Pallenberg’s house in Cheyne Walk, where the smack flowed while Keith was away in Nellcôte, South of France, starting the sessions for Exile On Main St. The Count was now juggling between Pamela, Jean Paul Getty Junior’s wife Talitha, and Marianne Faithfull.

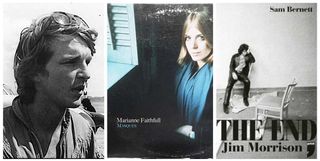

In her autobiography, Faithfull describes de Breteuil as “a horrible guy, someone who had crawled out from under a stone. Somehow I ended up with him… It was all about drugs and sex”.

In London, Morrison met up with McClure. He recalled a riotous evening “in the Soho clubs. The Bobbies busted us for being drunk and disorderly. Finally we decided to take a taxi to the Lake District, and got busted again. I guess taking a taxi all that way isn’t done ordinarily”. Morrison invited Alain Ronay to London.

“I moved them to the Cadogan Hotel, near Sloane Square,” says Ronay, who now lives in Los Angeles. “It was a time. No paparazzi. I never saw Jim sign one autograph. We went to the theatre, did all the usual things. I returned with them to Paris and moved into the apartment. Pam had her own life entirely. She wasn’t always around, but for the whole of June I lived with Morrison, practically 24 hours a day. I won’t deny he was a dark and complicated person, or that Pam was a basket case. But strike the fact that Jim was despondent, or drug addicted, or terminally depressed. He was living his dream, and that had nothing to do with rock. He was delighted at the success of L.A. Woman, but his pleasure lay elsewhere.”

Even so Morrison must have been getting studio withdrawal symptoms, since on June 15 he hooked up with two American street musicians who met him after sinking whiskey at the Café de Flore. Jim persuaded the buskers, who were crucifying Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s Marrakesh Express, to join him at a local jingle studio where they recorded a few drunken rambles including Morrison’s poetic ode to Pamela, Orange County Suite. The engineer gave Jim the tape box on which he scribbled a band name, Jomo And The Smoothies. The Lost Paris Tapes, as they became known, ended up in a white plastic bag from La Samaritaine department store which Morrison left at Phil Dalecky’s apartment but never retrieved.

One mid-June day, with Paris sweltering in a heat wave, Morrison collected kindling wood from the courtyard at Beautreillis for the fireplace. Carrying it upstairs with Ronay, he was soon out of breath. “What’s up with you?” Ronay recalls saying, “I’m 10 years older than you, and I’m not having a problem”. Morrison laughed the incident off, but was sweating heavily. He had started coughing up blood again so, at Pam’s insistence, he revisited an American doctor. He renewed a prescription for the treatment of pneumonia and respiratory problems.

In the final weeks of his life, Jim and Pam’s relationship reached breaking point. Faux suicidal, Pam often spent nights with the Count, while sharing her saner moments bullying Morrison over his lack of writing activity. Morrison wasn’t ready to admit defeat. He wrote to Elektra’s business director Bob Greene on June 28.

“Paris is beautiful in the sun, an exciting town, built for human beings. Speaking to Bill [Siddons] a while back I told him of our desire to stay here indefinitely.” Pamela had plans to buy an old property, maybe a disused church, where Jim could stop being a rock star and become a poet. Morrison asked Greene “for a sort of financial statement in general? Also a copy of the partnership agreement, if it was ever completed”.

Funds running out, he told Greene to turn over Themis to the trust of Pam’s sister and her husband – “we’d like to be completely clear of any involvement” – to organise new credit cards – “we could use them made out in both our names” – and to send a cheque for $3000. “House bills are catching up.” Touchingly he also asked Greene to make sure his dog Sage was well looked after. “Send Judy [Pam’s sister] 100 bucks for the dog”. It didn’t sound like Jim had any plans to return to California at all.

Jim loved going to the bookshops like Shakespeare And Company near Notre Dame. He was fascinated by the atmosphere of unrest in a Paris still recovering from the riots of 1968. He wrote brief verses, often sitting on a bench in the tranquil Place des Vosges – his favourite haunt. In The Sidewalkers Moved, composed a few days before his death, he wrote ‘Join us at the demonstration’.

Jim, Pam and Ronay spent June 28 in Chantilly; they had lunch at Hotel de l’Oise, where Ronay took the last known pictures of the singer. In one he’s hugging Pam. In another he gives Ronay his best lop-sided grin. “An idyllic day,” says Ronay. Back in Paris that night Pam got hold of more heroin. She later told friends that Jim started experimenting with the drug to keep her company, “snorting lines off his credit card”.

On July I Morrison was spotted by an American fan dining alone, drinking white wine and munching a croque monsieur in the bar Le Mazet after he and Pam had a blazing row in a neighbourhood restaurant near Beautreillis, witnessed by two German students who shared their table. Herve Muller hadn’t seen Jim since they went to a performance of Robert Wilson’s en vogue play, Le Regard Du Sourd [Deaf Man’s Glance], at Theatre de la Musique on June 11. Muller recalls that Ronay turned up during the interval, and they left the theatre with Morrison.

They retired to a cocktail bar called Rosebud, where Morrison was hassled by fans, moved on to La Coupole, then to Pam’s druggy haunts in Saint Germain accompanied by two flamboyant gentlemen – “minets bizarres” – before Morrison and Pam spent the small hours drinking at Café de Flore, Les Deux Magots, and Brasserie Lipp, with various debauched socialites. Muller never saw Morrison again.

He did phone the singer’s apartment around midday on July 3, however.

“A rather strange sounding Ronay answered the phone,” Herve recalled in his book Jim Morrison Au-Dela des Doors. “He said Jim and Pam have gone away for the weekend. And yet Jim Morrison had already been dead, apparently, for four or five hours, in a hot bath.”

Ronay thinks Muller may have called a day earlier. Morrison said he didn’t want visitors.

“So many people have exploited their liaisons; like that awful journalist [Tere Tereba] who bumped into Jim once at La Coupole restaurant, and suddenly she’s writing detailed dialogue about their supper [‘chocolate mousse for the ladies, please’] – it’s nonsense.”

Having spent most of five weeks living with Jim, Ronay moved out of the apartment and into a room at Agnes Varda’s house on Rue Daguerre, where the filmmaker was working on dialogue for the script of Last Tango In Paris with director Bernardo Bertolucci. The film, starring Marlon Brando, released in 1972, about an American exiled – and dying – in Paris was, some said later, influenced by the Morrison story.

On the morning of Friday, July 2 Morrison and Ronay walked in the Marais. Morrison bought Pamela jewellery. They ate at Ma Bourgogne, a restaurant specialising in the rich food of Alsace, where Morrison’s hiccoughing fits returned. Jim called at the cobblers to collect some boots. Despite Ronay’s insistence that Jim was not despondent he was agitated. After beers at Café de Phare, Ronay left for a dinner date with Varda. Morrison begged him to stay: “One more short beer! C’mon. Do it for an old friend”. Ronay agreed. Morrison’s hiccoughs were raging now. Ronay looked at Jim alive for the last time in the Place de la Bastille. He saw a face like a death mask. Sensing his stare, Morrison asked: “Well – what did you see?”.

At Varda’s house, Ronay recounted his unsettling afternoon. They went for dinner around the time Jim and Pam supposedly went to eat a Chinese meal. Ronay had recommended the couple go to see the film Pursued, a Freudian Western set in New Mexico, starring Robert Mitchum, about a young boy whose family is wiped out. What happened in the hours between Ronay’s departure that late afternoon, and the eventual death of Jim Morrison now becomes a mystery.

At 5.40pm the following day, July 3, Pamela gave her official statement to policeman Jacques Manchez, via Ronay’s on the spot translation. The previous evening, she told Manchez, she felt ill, so Morrison dined alone in ‘Le Quattier’, Rue Saint-Antoine where he apparently ate sweet and sour Chinese washed down with plenty of beers. When he returned they – or maybe just Jim – went to the cinema Action Lafayette to see La Vallee de la Peur/aka Death Valley/aka Pursued. Much to Morrison’s annoyance the movie was badly sub-titled.

Bored and opiated, Jim returned around 1am, July 3. As usual they built a fire – despite the warmth of the night. Jim started drinking whiskey. He tried to write at his desk, in the spiral-bound reporters pad that will become known as his last French Notebook. For the third day in a row he sniffed heroin off a mirror. He and Pam watched a sequence of their on-the-road-in-Europe Super-8 cine movies.

Pam tells Manchez: “My friend [not once in her statement does she refer to Jim by name] appeared healthy and seemed very happy – but I noticed there was something not quite right about him. Later we played some records that I found in the bedroom and we played music for two hours lying on the bed… I think we fell asleep about 2.30 but I can’t say when exactly. The record player turned itself off.”

Manchez asks: “Did you have sex with the deceased?” Pam replies: “No, we didn’t have sex last night. About 3.30am, I think – there isn’t a clock in the bedroom – my friend wakes me with the noise of his breathing. He was so noisy I got the impression he must need help. I wanted to help my friend. I asked him, did he want a doctor? No. He said he was OK, and he was going to take a hot bath. He got in the bath and then he called me because he felt sick… I took him in an orange saucepan, and my friend threw up the meal he’d eaten and I noticed… some blood clots.

“He is sick three times. Third time it’ s just blood… I tipped the pan into the basin… then I washed it. Now my friend says he feels strange. ‘But I don’t feel ill enough for you to call me a doctor. I feel better now… It’s over… Go to bed!’ he tells me… ‘I’m gonna stay in the bath, and I’ll be in with you later’.

“I thought he seemed better, because he’d been sick, and his colour had returned, so I went back to bed feeling reassured. I don’t know when I went back to sleep, but I woke up later and realised my friend wasn’t in bed with me. I ran to the bathroom, and saw he was still in the bath with his head back as if asleep. He had blood round his nostrils. I thought he must be ill, or he’s unconscious. I tried to pull him out of the bath but it was impossible for me. At that point I called Mr Ronay and he came with Mrs Agnes Demy [aka Varda], and they called the police station for me.”

That was Pam’s statement. What she didn’t tell the police, but did tell Ronay was this: Jim returns and listens to Doors albums, fixating on one particular song – Not To Touch The Earth [from the album Waiting For The Sun, which references the death of John F. Kennedy]. The couple take more heroin. Jim carries on drinking.

At 3am the couple start nodding out on the 86% pure smack that’s slithering through the French underground scene. If Pam’s testimony to the police is to be believed, she is woken by Morrison’s coughing fit. He runs a bath. The vomiting. The sleep.

As dawn breaks, Pamela wakes to realise that Morrison is still in the bathroom. In an awful reminder of the Cars Hiss By My Window lyric – ‘Can’t hear my baby, though I call and call’ – she thinks she hears him cry out, “Pamela – are you there?”. On finding him in the bath, Pam realises Jim Morrison is either dead or dying. She calls Ronay and Varda, and possibly Count Jean de Breteuil.

Until recently, these have been accepted versions of events. In 2007, however, Sam Bernett, a French-born former New York Times journalist and author of several books on French culture, published a book that confirmed a story that had circulated around Paris for 36 years.

Sam Bernett had been the house manager of the Rock’n’Roll Circus since its opening in 1969. According to Bernett, Morrison turned up at the club around 1am and ordered a bottle of vodka. Morrison was no stranger to Bernett either.

Bernett: “I was in the club that night July 2 and Jim came in at about 1am, July 3. He was at the bar as usual. He was with some friends who I didn’t know. He was expecting people to bring him some stuff for Pamela. He was often in there doing that, or going to little cafés and dealers in the streets in Saint Germain. He was waiting. He drank, talked, I listened but I wasn’t always next to him. I bought him drinks. About 2am two guys came and then for 20 minutes he wasn’t at the bar. He disappeared.”

The two men were apparently dealers connected to Jean de Breteuil. Their real names have been lost to time, but it’s alleged that one was nicknamed ‘Le Chinois’, the other ‘Le Petit Robert’. Bernett was next alerted by the cloakroom girl on the first floor.

“She was worried because one door had been locked for a long time and people were complaining they couldn’t get in. They banged on the door: ‘Anyone there?’ No answer. So I checked with her. No answer indeed. I didn’t know Jim was behind the door. I called my security guy to smash the door open and inside was Jim. Sitting on the loo with no reaction, like he’s sleeping or knocked out, his trousers slightly down.

"He was sitting with his head forward and his arms down – like a dead guy, actually. I shook him, I looked at his face, still no reaction. He had foam on his nose and lips. I told the girl to get a doctor. I had a friend, a customer there every night – he was in the club. He came, looked at Jim and started a little check-up, then he looked at me and said, ‘That guy is dead’.”

Bernett made to call the emergency services but the two dealers reappeared. "‘He’s not dead. He’s just fucked up’. [they said] ‘Don’t call the police, don’t call his family. We take him home, we know where he lives’. I said, ‘That’s impossible! We have to call the police and the medical people’. ‘No!’ they say. ‘Forget it. We’ll take him and we’ll use a back door’. Then the club owner’s right hand man appears and confirms: ‘No trouble, no police. We don’t want any scandal. They’ll close us down’. I said, ‘You can’t do that!’. ‘No, I’m the boss – you do what I say’.

“The two guys packed him up and they took him out the club through the Alcazar out t the street door opposite the Rue de Seine, and the entrance to the Circus. The Alcazar had closed, the cabaret was over, apart from a few people who looked to see what was happening. They took him to the apartment. I was told this – they put him in the tub and waited an hour-and-a-half before calling the paramedic. Pamela was in the apartment, out of her mind, screaming. Completely stoned.”

Bernett maintains his silence for 36 years, and then writes a book, The End – Jim Morrison [2007, Prive] outside of France it is greeted with scepticism. But in a new interview with Classic Rock, Patrick Chauvel (now an award-winning war photographer – a profession that risk their lives to report the truth) bears out Bernett’s version.

Says Chauvel: “Jean-Marie Riviere, L’Alcazar boss and a king of the Parisian music halls and night club scene got involved. He spoke to several guys including me, and said, ‘We’ve got a problem here’. They called in a doctor and asked us to stay around and, to make the [story] shorter, we had to take him out of there because if they find Jim Morrison dead in the club, that’s the end of the club.”

In his capacity as an employee, Chauvel did what he was told. “Was I scared? Hmmm. It was a waste of somebody fantastic. Nobody knew about it apart from the few guys, the boss, Sam definitely, and maybe Cameron [Watson, a Parisian club DJ]. They all just wanted to keep it real quiet. It was an embarrassment so they took him via the tunnel between the clubs, which connected the cloakrooms, and up the stairs to the backstage street door. The boss was afraid of having a doctor or a newsman say anything, so they evacuated Jim, et voila, into the car.”

And he helped?

“Yes, I helped carry him in a blanket. I can’t say 100% that he was dead, but he wasn’t moving. That’s for sure. Yeah, I thought ‘This is bizarre’, but I’d just come back from Vietnam. I’d seen a lot of weird things. Anyhow, he was then put into the back seat of a Mercedes. I don’t know who drove the car. They took him home, is what they told me. I didn’t see the car leave, no. I helped put him in and then went back inside the Circus. They wanted everything to look as normal as possible. I remember they put him into the back seat very gently, and that’s why I thought he might still be alive. I saw that shape, that heavy shape.”

And what did Chauvel think had happened to Jim? “I heard that the guy he was used to getting drugs from had changed, been arrested or something,” he says. “So Morrison got involved with a new guy that night, and the heroin wasn’t the same at all. It was a lot more pure, and Jim didn’t know that. And he overdosed.”

If this account is correct, and many in Paris believe it to be, the official Pam Courson story must be substantially fictional. Chauvel even recalls the people who assisted.

“I knew most of them by sight. I remember one name: Dominique Petrolaci, a Corsican. He was the head barman and a good friend who got me my job. He shot himself shortly afterwards at a party – put a shotgun through his mouth in front of everybody.”

Theories surrounding Jim’s death are legion. During research for this piece a Parisian source offered the notion that Pamela wasn’t in the apartment that night, but was sleeping with an extremely famous [unnamed] French celebrity. But Count Jean de Breteuil was definitely spotted hanging around the street with a friend by Alain Ronay.

“He looked like a ruffian,” Ronay told Varda who recognised the man as well. “I wanted to spank his tailor,” was Ronay’s quaint appraisal.

We’ll never know whether Pam was home when the men arrived with the body. What we do know is Marianne Faithfull’s claim that Pamela phoned Jean de Breteuil, at around 6am.

According to Faithfull’s autobiography, “We were staying at L’Hotel. Suddenly Jean had to leave. He slammed out the room. He didn’t come right back. He returned in the early hours very agitated. I was fucked up on Tuinals. For no reason he beat me up. I asked him, ‘Did you have a good time there?’. He replied: ‘Get packed, we’re going to Morocco’.”

Faithfull claims Jean was “scared for his life. Jim Morrison had OD’d, and he had provided the smack. He saw himself as dealer to the stars. Now he was a small time dealer in big trouble. Jean took me to Tangier. It was a disaster. We were horribly strung out. In a panic before he left Paris he got rid of all his drugs.”

To make matters worse, the Count had been boasting that it was he who had sold Janis Joplin the fatal heroin that killed her in October 1970. On Saturday July 3, Jean and Marianne arrived in Marrakech and stayed with his mother at the infamous jet-setting hang out Villa Taylor. The noted musicologist Roger Steffens had dinner with them and others that evening. He described an extraordinary night in a letter to his family dated July 9.

“The Countess’s son, Jean, the handsome 21-year-old jet-setting playboy who inherits his late father’s title this November, arrived unexpectedly in Marrakech last Saturday,” he wrote. “The pair had just come from two violent days in Paris, which began with an auto crash, included an attempt by Jean’s best friend to slash his wrists and culminated in a call from another old girlfriend of Jean’s, Pamela Courson, who was staying in Paris with her husband [sic] Jim Morrison, lead singer of The Doors. She begged Jean to rush over to her place, and when he arrived they found Morrison dead in the bathtub of an apparent overdose of drugs. All these being too much, Marianne and Jean hopped a plane for Marrakech, and a peaceful, retreating week.”

Today Roger recalls: “Jean and Marianne seemed very high and spaced out as they recounted the story. They were very upset… I met Jean through his mother, the Countess de Breteuil, second wife and first love, though a commoner – of the late Count. Jean was the apple of his mother’s eye, but in reality a profligate drug-dealer who left a long trail of disasters in his wake.”

He certainly did – they included Talitha Getty, Pamela Courson, Jim Morrison and himself. De Breteuil died within the year in Tangier, of a massive heroin overdrose.

Marianne Faithful declined to be interviewed for this story.

Alain Ronay and Agnes Varda reappear in the official story when Pamela calls them at around 8am on Saturday, July 3.

“Please call an ambulance. I think my Jim is dying. He is in the bath. He has blood around his nose. Please call for me.” Varda now says: “Pamela called my house and I answered. I called for the firemen – les pompiers. In an accident you always call them, they are the first assistance – like paramedics. I told them: ‘Go right away to this address. There is a scene there where maybe someone is out of life’.

Ronay gave the exact address. We went together, we arrived, and the fireman said, ‘It’s too late – he’s already dead’. Then the doctor comes [Max Vasille, Varda’s family doctor], and does what doctors do. But it was hopeless.”

What do Varda and Ronay make of Bernett’s account? To Ronay, “Bernett’s story about the toilet is ridiculous. Check the physical probability. People would notice a body. How did they carry it out of a club onto Rue Mazarine into a taxi and up three flights of stairs without anyone seeing them? It’s impossible.”

Agnes Varda is even more damning. “I never read his book but I know what he says is rubbish. All I know is I saw Jim Morrison a few days before he died and he didn’t look good. He was not in good shit – this I remember. Then Pamela called me in the morning and she says he doesn’t look good. Alain calls me the day before and Jim’s not in good shape – so it was nothing special. He wasn’t well. But look: I’m not the one holding his hand. Don’t ask me what other people think. Don’t quote me on someone else’s silly book.”

Is it silly? Bernett and Chauvel don’t think so.

“At first I didn’t think the official story was bullshit,” says Chauvel. “I thought they took him back and he died in the bath, trying to get his wits together. But why send for a doctor before they carried him out? As soon as it happened they closed down the toilets, and put a guy on guard and said they were broken. It was the women’s toilets. I’m not the only one telling this story. I don’t think there’s any doubt that he did not faint in the bathtub. He was definitely there that night. There is no doubt about that.

“Next day they said, or the rumours said, they stripped him and put him in that bath tub in very hot water – very hot so the doctor who confronted the death couldn’t take an accurate temperature of the body. He would make a mistake [estimating the time of death] so maybe that’s true. I don’t know.”

Far from being a story that lay untold for over 30 years, rumours were rife in Paris, with even local papers picking up on it.

“I remember a newspaper article [in Le Parisiene] that appeared a few days after Morrison’s death,” recalls Chauvel. “[It] said – rough translation – ‘Jim Morrison is dead but his corpse keeps moving around’.”

The first official who saw Morrison’s dead body was Alain Raisson, the French fireman/paramedic. Now living in Rio, he confirms the story of his arrival at the apartment with a team of five. The body was warm, so the team hurriedly tried to revive the singer.

“We carried him onto the bed, to do cardiac massage,” he says. “We tried to revive him and failed. It was a short, intense, very real and brief encounter.” The warmth, they realised later, had come from the still warm bath. The doctor who arrived a few minutes later was amazed when told that the man dressed in a Moroccan gown was only 27.

“He looks much older. I would have said a 57 year-old,” the doctor exclaimed.

He was happy to suggest that the patient had died of natural causes. Heart failure, possibly brought about by respiratory problems, was his verdict. No need for an autopsy. When Bernett wrote his book he contacted Raisson and the chief paramedic. “The fireman told me he knew Morrison died much earlier. He said ‘This guy’s been dead for a couple of hours, at least’.’ The police commissioner told me the same thing. ‘We knew there was something wrong with the story’, he said. ‘But, look it’s summertime and I’m going on vacation tomorrow’. He wanted to wrap it up quick so he signed the papers. He didn’t believe the story he was told in the apartment. He said it was strange and phoney, but he let it go.”

By 9am that Saturday the local police were swarming all over Rue Beautreillis and a small crowd of onlookers had gathered on the street. Courson and Ronay managed to leave the apartment on two occasions: to contact an undertaker, and to secure a Death Certificate at the Town Hall – much to the Chief of Police’s annoyance. Before he arrived, Pamela managed to flush her stash of heroin down the toilet and burnt a selection of Jim Morrison’s letters and notes.

“Why?” she was asked later, as the grate smouldered. “They mustn’t read this… this stuff,” she announced, in her singsong voice.

In the small hours of July 3, some hours before the official time of death, a strange thing happened. At club La Bulle, DJ Cameron Watson made an announcement over the tannoy after being approached by two men. Cutting the music Watson called for silence. “Ladies and gentlemen, Jim Morrison has died tonight at the Rock’n’Roll Circus”.

Rumours soon tore through Paris. The Corsican mafia had killed Morrison. A Marseilles hit man had assassinated him. He’d died after a fight with the Count and his henchmen. He’d committed suicide. The CIA had given him the fatal OD. There were bloody daggers under his bath. He’d got two bullet wounds in the head. There were bruises on his body… Amidst the conjecture, what is certain is that – rather than take the body to a morgue – Courson agreed to the French tradition of keeping Morrison’s corpse in a coffin in the bedroom. Every so often an ‘ice man’ turned up with large blocks and canisters of dry ice to keep the body relatively fresh.

“That’s the way we can do it in France,” says Varda. “The Spanish do it. The Jews and Arabs do it. The body is in good condition. [We did the] same with my husband Jacques Demy. We don’t put it in a fridge or under the bed.”

But contrary to reports that Pamela slept with Jim’s body, Varda says, “Pam was not alone after Jim died. She stayed at my place and she went back to the apartment in the day. People were with her at all times. The secretaire [Robin Wertle] was there. The police and the undertaker had keys to Rue Beautreillis. When people say that Bill Siddons organised Jim’s funeral at Pere Lachaise – no, he did not. I did that. I helped with all the arrangements. It wasn’t easy getting a foreigner into Pere Lachaise.

"Anyway, Jacques and I organised with Alain. The secretaire [Wertle] did nothing. I only noticed her at the funeral when I saw I was standing with another woman. There was no priest. It was all done quickly and properly. Just normal. Is it lucky to have been there? Would you love to have been there? The man was dead! I wish he were still alive. He cannot be replaced. Voila!”

Ronay’s twist is different again. “I buried Morrison in Pere Lachaise,” he says. With deadly irony, Morrison apparently visited the cemetery at the end of June and was much taken by the artistic bent of the inhabitants. “It was my idea. I was the only person at the funeral parlour. I picked the site. I went alone. Agnes had nothing to do with it. Bill Siddons can’t take credit. Can he speak French? Give me a break. Enough already. Robin Wertle? Nothing to do with it. She’s disappeared. I guess like in all good mysteries she reappears later.

“Pam was contacted by Siddons. She had no money and she was losing control. Agnes was good to her. Agnes drove me to the funeral. Pam wanted Jim buried in L.A. for God’s sake! What? And have bus tours stopping every two hours?”

On Monday July 5 Doors manager Bill Siddons received a call from Clive Selwood in the London Elektra office telling him, “Three journalists have called me and asked if Morrison is dead”. Siddons spent six hours calling Pam, reaching her at noon.

Siddons: “I told her, ‘I’m a friend. I’m coming to Paris now’. It was a weird flight. I wasn’t going as an official representative of The Doors; I simply went to help her. I got to the apartment on Tuesday morning while all the local workers were in the cafés drinking their coffee and brandy. Pam was alone. She was coherent, but totally distraught. She’d hit the wall. I cooperated as best as I could.

“I was only 21. I had no tools to deal with this. We ran round the city all day. She filed a report at the American embassy [the form ‘The Death of an American Citizen Abroad’] and we went to the funeral house.”

There was a story that he’d arranged for a more expensive white ash coffin in which to bury his friend. “That’s untrue,” he says. Siddons’ first impression on meeting Jim Morrison when he was the Doors teenage roadie had been, “he scared me to death”. He had no desire to see his friend’s body, which was now finally sealed for burial. The fact that no one from The Doors’ camp saw Jim’s body became one of the cornerstones of the ‘Jim is alive’ conspiracy theory. It’s not one to which Siddons subscribes.

“We buried Jim on Wednesday 7,” he says. “It was morning. His body was picked up at the apartment. I travelled with Pamela and the secretary Robin Wertle to the cemetery. Ronay and Varda followed separately…”

There were four unknown pallbearers. “Everyone was distraught, but it was a nice little goodbye ceremony. Pam said some words. I don’t remember what. [She recited some words from Morrison’s poem The Severed Garden]. I don’t know what happened to Robin. I haven’t spoken to her in 20 years. She wanted nothing to do with the obsession. She was clear on that. She served Jim and Pam very well – and Jim and Pam are gone. I have a high regard for Robin. She was a class act.”

None of The Doors, or anyone at Elektra, was invited to the funeral.

“But that’s not weird at all,” says Siddons, who released a statement on Thursday, July 8 after flying back with Pamela to Los Angeles. “We – I – wanted the funeral low-key. I saw what happened with Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. Jim was buried with the respect and consideration he deserved as a great poet and artist. I don’t know about the theories surrounding Jim’s death. All I know is Pam told me he died of a heart attack. She simply said, ‘I went to check on him… and he was no longer with us.’”

Back in LA, the remaining Doors heard the news via Siddons’ telephone call.

Ray Manzarek says, “In one way I wasn’t surprised at all. Jim broke the circle. When I heard he was dead I said, ‘See! That’ll teach yer – you can’t burn the candle at both ends!’. Yeah, I thought his excesses would do him in. Of course we were devastated. We went into the studio the next day to work. It was security. It was like my brother had died.”

James Douglas Morrison’s final notebook contained the harrowing message: ‘Last words, Last words. Out’. Also a chilling self-assessment: ‘Regret for wasted nights & wasted years – I pissed it all away – American Music’. July 3, 1971. Paris. It was to be Jim Morrison’s last hitchhike into the unknown.

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 148, August 2010.

The Doors: the story of Strange Days and the madness of Jim Morrison