The Douglas Corner Café has given a leg-up to some of Nashville’s biggest stars: Garth Brooks, Trisha Yearwood, and Blake Shelton all played showcase gigs there in their formative days, looking to impress the local A&R men. A bastion of conservative country, it’s the kind of downtown hangout where stetsons and cowboy boots are as ubiquitous as the music itself. It’s certainly not the sort of place where you’d expect to see a bunch of noisy southern longhairs with a classic-rock fixation. Yet that’s where the Kentucky Headhunters found themselves at the back end of ’88, tagged onto the end of a record company shindig for Texan hotshot Lee Roy Parnell.

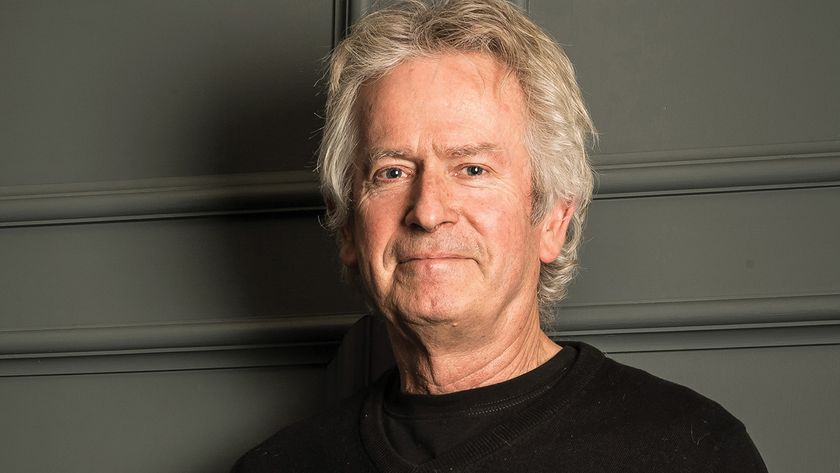

“The place was jammed and there was all this expectation,” recalls Headhunters singer/guitarist Richard Young, “but we never even made it through the opening song. When I hit that very first note, it was like somebody had yelled: ‘Bomb!’ It cleared the room, people were headed out the door as fast as they could. The only people left were the waitresses, the bartender, the sound guy, our two buddies and Harold Shedd from Mercury Records. Harold walked up to us and said: ‘Man, I don’t know what I just heard and we may be cooking hamburgers this time next year, but I think we’ve gotta try this.’ He called up the next day and said: ‘Let’s go!’ It was almost unbelievable that somebody would say yes to us, because we’d been kicked in the butt so many times. But it changed our lives forever.”

The Headhunters had already been active for 20 years by then. Having begun in 1968 as Itchy Brother, based in rural Kentucky, they’d been struggling to find an audience for their rootsy stew of hillbilly blues and cranky rock’n’roll. A number of record labels had shown interest, but a combination of bad luck and rotten timing had thus far conspired to leave them hanging.

Mercury’s sudden leap of faith was justified, however, when the band’s belated debut, Pickin’ On Nashville, was released in October 1989. Propelled by a string of successes on the US country charts, the album won a Grammy and sold more than two million copies. “It’s true what the people in Nashville said about us, that we were unpredictable and unmanageable,” Young says, reflecting on the Headhunters’ reputation as southern outriders. “But that album was the catalyst for everything. It gave us a stripe on our shoulder that allowed us to be who we are.”

Identity is central to the Headhunters story. Raised on a seven-acre farm in Glasgow, Kentucky, Young and his brother Fred belong to a family whose roots have been tied to the soil since the American War of Independence. Like many music fanatics who came of age in the late 60s, the Youngs fell in love with heavy electric rock, particularly the British kind. “We were just kids when we formed our first band over at our grandma’s house,” says Richard. “We’d be listening to English rock and nothing else: John Mayall, Cream, the Stones, Free, all those great bands from over there.”

Formed with their cousins Greg Martin and Anthony Kenney, Itchy Brother’s primary objective was to emulate their heroes from across the Atlantic. And the local environment, inevitably, played its part. Folk, blues and country music were in the air. Literally. “It was the greatest thing in the world to be a part of that farm community, which was made up of both white folks and African-Americans,” Young explains. “Back then people just sang as they worked. I remember some of the old guys singing Lefty Frizzell and Hank Williams, then in another field you’d hear gospel and black spirituals. It was such an education. We may have been staunch rockers, but all that stuff was seeping into our heads the whole time. That combination of blues, country and English rock gave us a clear foundation of what we were going to be.”

Local label King Fargo put out a single, Shotgun Effie, in the early 70s. There were sporadic TV appearances too, and plenty of raucous gigs that earned them a pack of hard-core fans, yet they seemed like a band out of time. Relocating to the big city – namely Atlanta, Georgia – didn’t exactly further their prospects either. “We were living down there by seventy-seven, and found that the bars had all turned to discos,” Young says ruefully. “Everybody was dancing like fools to the jukebox. It was so depressing. The heyday of southern rock had pretty much worn out by then. And when Ronnie Van Zant and those guys from Skynyrd died, we felt that was the last hope. So we came home and licked our wounds.”

The following year they met Mitchell Fox, head of the New York office of Swan Song Records, Led Zeppelin’s label. Fox adored the Itchy Brother sound and wasted no time in recommending them to Zep manager and label overseer Peter Grant. .

“We were hoping to be the first all-American band on Swan Song, then John Bonham died. So we never even got to play them the tapes after Mitchell had flown over to meet Peter Grant. Us signing to Swan Song was probably a lot closer than I’d allow myself to admit.”

After another knock back, this time from Atlantic/Atco Records, a disconsolate Itchy Brother split up in 1982. The Young brothers found session work as sidemen, before heading to Nashville to try their luck as songwriters for the famed Acuff-Rose publishing company. It proved an enlightening experience. “I met a guy called Whitey Shafer, who’d written stuff for Lefty Frizzell, and he told me that I needed to write about what I knew,” Richard recalls. “It was the best lesson I ever had. We came home and started writing party songs and stuff like Dumas Walker.”

When they decided to revive Itchy Brother in 1986, this time as The Headhunters (the ‘Kentucky’ came later), Dumas Walker quickly became a highlight of their live shows prior to its eventual home on their Pickin’ On Nashville album.

The band’s fortunes continued to rise following their breakthrough success. There were tours with Hank Williams Jr. and others, another big-selling album with 1991’s Electric Barnyard, and collaborations with Gov’t Mule and the great Johnnie Johnson, Little Richard’s old pianist.

A number of line-up changes during the 90s and beyond put a crimp in their progress, but the Kentucky Headhunters have soldiered on. They’re one of the last authentic southern rock bands still standing. Along with a lack of visibility (they toured Europe for the first time in 2016), and Richard being the father of Black Stone Cherry drummer John Fred Young, this has afforded them a semi-mythic status.

Their latest album, their eleventh, is On Safari. Recorded just after the death of the Youngs’ father, it’s a fitting tribute to the band’s family heritage, full of grainy voiced rock’n’roll songs that reference the American south, their tangled musical roots and the old homestead.

“When the studio time came up, on the Tuesday after dad was buried, we felt we weren’t ready,” Richard explains. “We ended up with three days left in the studio, so we went in there, still too out of it to tune our guitars, and to this minute I don’t know how we managed to record the album. There’s some crazy stuff on it. Somewhere in the back of my mind I knew there was a higher spirit working in the studio with us. No doubt about it.”

As for the Headhunters’ decision to finally tour Europe, Young credits John Fred and his BSC bandmates for giving them the necessary kick up the backside: “Last year the boys got back from an arena tour of the UK and they all cornered me, saying the Headhunters needed to go over there,” says Richard, whose fear of flying is a major reason for his prior reluctance. “A week later, John Fred called to say that they’d got us on Sweden Rock, which is the biggest rock festival in Scandinavia. Then they came back with the Ramblin’ Man Fair. We ended up being booked for eight straight shows in Europe. After so long, I thought it might’ve cooled off for us over there, but the crowds were unbelievable. It makes me so proud that, at sixty years old, we proved that we could still really play.”

On Safari is out now via Plowboy Records

Kentucky Headhunters: “Black Stone Cherry told us to put up or shut up”