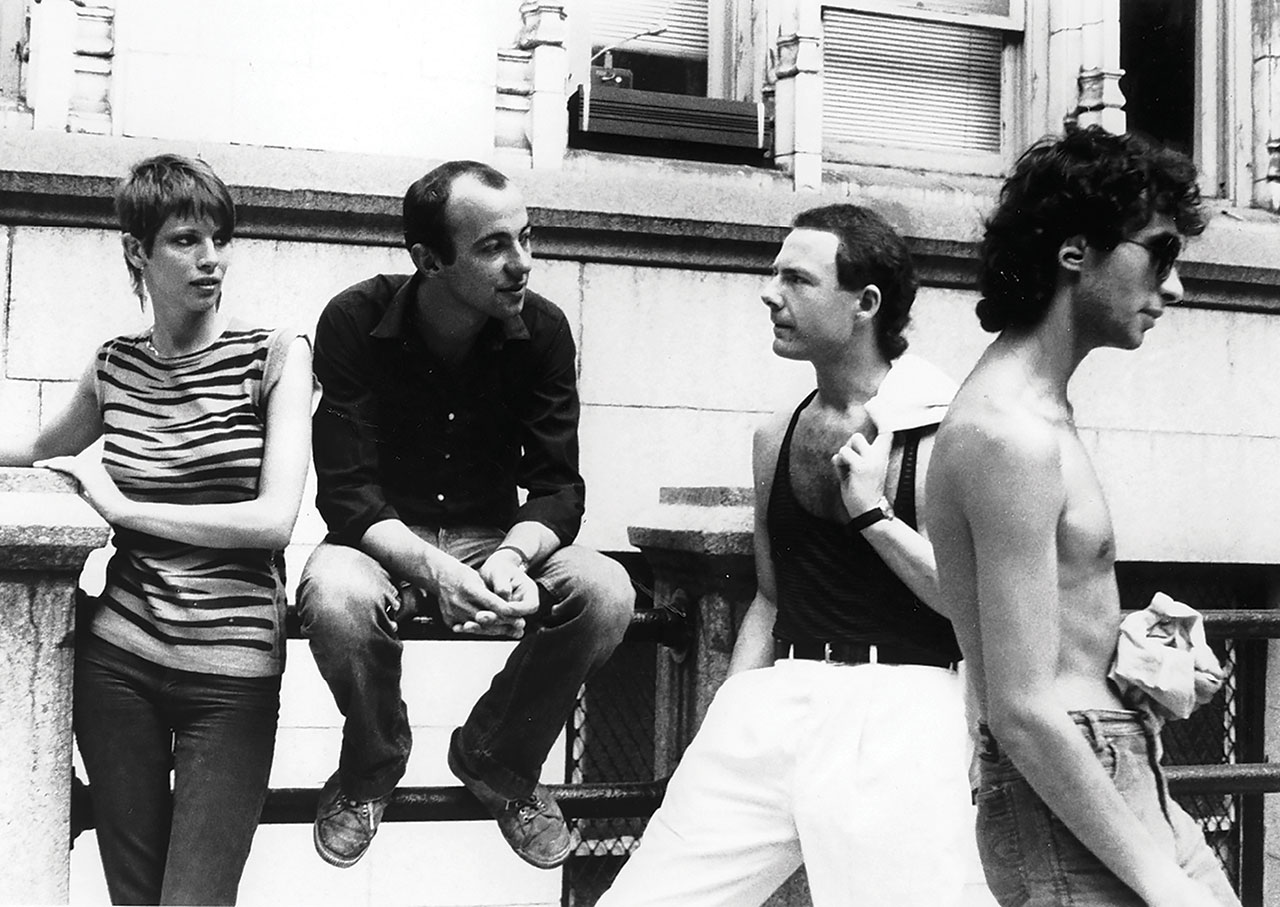

It’s the middle of May 1980 and Robert Fripp, ex-XTC organist Barry Andrews, bassist Sara Lee and drummer Johnny Toobad, collectively known as The League Of Gentlemen, have finished their set of what the ex-King Crimson guitarist calls a new wave instrumental dance band. Playing small clubs where the dressing rooms are even smaller means the tiny confines are crowded with well-wishers, people in search of a good time and, with a grim reliability, men cornering Fripp to engage him in a fervent discussion on philosophical issues.

Drawn perhaps as a result of Fripp’s very public abdication from King Crimson in 1974 to go on a spiritual sabbatical, Barry Andrews recalls that this was the typical scenario of many such aftershows with the band.

“Robert’s connection with Crimson conjured up a lot of boring fuckers in the dressing room: all very earnest, geeky blokes. It even got to Robert – who was single at the time and up for some action – that instead of basking in the oestro-waves of well-deserved post-show girly adulation, he was being cornered by yet another sweaty bloke asking for some spiritual/musical guidance.

“Johnny said that if Fripp wanted to get rid of these Seekers After Knowledge, he could try pretending to sell them heroin. Gamely, Robert did exactly that. His performance as a drug dealer was less than convincing – ‘Would you like to buy some smack? It’s really good stuff’– but it certainly did the trick.”

Any account of Robert Fripp’s route from retirement in 1974 to his emergence spearheading a new incarnation of King Crimson in 1981 will usually include a couple of notable stopovers. His cautious return to the music industry included supplying the soaring guitar line on the title track of David Bowie’s “Heroes” in 1977. That same year he went back on the road as part of Peter Gabriel’s touring band, albeit under the pseudonym Dusty Rhodes, performing not quite on stage, but behind a curtain. With a producer’s credit on Gabriel’s second album and Daryl Hall’s Sacred Songs, he relocated to New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, which resulted in appearances with Blondie and others on the emergent new wave scene.

From there, in 1978, very much relishing the role of an Englishman in New York, he launched his personal manifesto that mapped out his career for the next few years. Entitled The Drive To 1981, it was, he says: “A campaign on three levels. Firstly in the marketplace, but not governed by the values of the marketplace; secondly, as a means of examining and presenting a number of ideas which are close to my heart; thirdly, as a personal discipline.”

The ‘number of ideas’ close to his heart included his first solo album, Exposure (1979). This was followed by God Save The Queen/Under Heavy Manners (1980), and, perhaps most significantly in the context of what was to come next, The League Of Gentlemen, formed in March 1980. When considering the reformation of King Crimson in 1981, the importance of The League, as they were known, is often overlooked. It’s not hard to understand why in a way. Their short, four-to-the-floor instrumental tracks, with titles like Inductive Resonance, Dislocated, Thrang Thrang Gozinbulx and Ooh! Mister Fripp contained skewed, quirky melodies, animated with a punkish pace.

In their live sets, with about an hour’s worth of material, those strange riffs were combined with Fripp’s extraordinary out-there signature guitar, forming a piledriving avant-pop for those who like their dance music with a generous twist of dissonance.

With “an emphasis on spirit rather than competence”, as Fripp succinctly put it, The League Of Gentlemen toured the clubs and colleges of Europe, Canada and the United States for seven months, totting up a total of 77 shows. They seemed about as far removed from virtuosic ruminations of Crimson as it was possible to get. Their one posthumously released self-titled album didn’t adequately convey the band’s dance-orientated velocity. Yet The League were the testing ground for much of the musical vocabulary that Fripp would come to refine on 1981’s Discipline.

Barry Andrews, whose band Shriekback last year released Without Real String Or Fish, their 15th album, doesn’t recall too much about his first encounter with Fripp during the making of Exposure, his attention diverted elsewhere. “I mainly remember Peter Hammill, being next to overdub after me, necking half a bottle of brandy before going in the vocal booth in order to ‘silence the conscious/critical part of my mind’, or words to that effect. I thought that sounded like a rationale that might be useful to me in the future.”

- The Top 10 Best King Crimson 1970s Songs

- The Story Behind 21st Century Schizoid Man by King Crimson

- Buyer's Guide: King Crimson

- The Robert Fripp Quiz: how well do you know King Crimson's mainman?

The next the organist heard from Fripp, now residing once again in London, was after the guitarist pushed a note containing an invitation to form a band under the door of what Andrews describes as a “squalid squat” in Kings Cross. “I must say, I rather liked the idea of him doing that in his nice suit.”

With Sarah Lee and drummer Johnny Toobad recruited from punk outfit Baby And The Black Spots, they had what to Andrews felt like a less than promising first rehearsal. Adjourning to the pub after a few numbers, Andrews recalled Fripp was in a sanguine mood.

“Robert said that he wanted to revolutionise rock’n’roll with the people around this table. I wasn’t too sure if this was going to be possible, given what I’d just heard. But hey, it meant going to stay in a guest house in Dorset, and they were about to throw us out of the squat…”

With Andrews’ frenetic keyboards acting as the glue between the rhythm section and Fripp, he was content to let the guitarist oversee the direction of the music.

“I think the fatal flaw in the League Of Gentlemen was that it was clearly put together around Robert’s idea and musical proclivities, and me and The Toobads, as they were known, were cast as though in Robert’s movie: ‘He was a 70s guitar hero, they were a bunch of North London chancers. Now they have to go on the road…’ We were encouraged to pretend it was a real band. I didn’t really see the point of that. Robert was the guitar star, we were his backing band. What was the problem?”

If there was a problem, it was that Fripp was actively considering a return to what he termed ‘first division’ music making. In Fripp’s model there existed three categories of music making. His solo Frippertronics basked in the third division and essentially concerned research and development, representing, he said, “interesting ideas and civilised lifestyle, but you won’t earn a living. Second division will earn you a living if you graft and you can get professionally respectable, but you won’t change the world”.

During its tenure, The League hovered precariously somewhere between the two. Several pieces in their repertoire bristled with the sizzling lines of cyclical guitar music Fripp was clearly itching to take further. Within the heat of a gig, it was common for them to hurtle from dissonant and explosive energies down to simplistic and ethereal moods within seconds. Their ability to reconcile those contrasting elements had a blunt, unrefined efficiency. Though sometimes lacking subtlety, the conversion and exchange of different time signatures, where the melodic heavy lifting alternated between front and back lines in the group, was crucial to the development of Fripp’s next step.

As they undertook a final string of UK dates in November 1980, Fripp was by now contemplating a return to that first division, and with it, access to the best musicians, better budgets and a much wider audience. When The League Of Gentlemen played their final show at the London School Of Economics on November 29, Andrews sensed the band had run its course.

“I think I was feeling more like part of some kind of Gurdjieffian social experiment gone wrong than was comfortable. And kinda patronised, if I’m honest. I recall we had got together to try to do some tunes and bring them back to Robert, in a half-baked attempt to try to be more than lab rats. And when I rang Robert to tell him, he said, ‘I’m putting the band on hold.’ One of his reasons was that he was sick of ‘playing with people who are drunk’. That was us told. Fair enough, actually. And a bit of a relief all round.”

Although wary of returning to the madness of the music business that had caused him to quit in 1974, Fripp was ready to do so, but this time under his own terms, noting: “You’re on a tightrope… Either way, you have to jump, and if you fall, you lose your health, sanity and, occasionally, your soul. But you just might fly away. So there’s your choice.”

The drive to 1981, now at an end, had taken him to his final destination: King Crimson.

Beat Poets Part One

After their first gig at the end of April at Moles, a tiny club in Bath, Fripp noted in his diary, “Well, we did it. This band will be colossal – it’s that good… For me, this is the band I’ve spent four years getting ready for.”

Now consisting of Adrian Belew on guitar and vocals, Tony Levin on bass, Stick and backing vocals, and Fripp’s old sparring partner Bill Bruford on drums, the release of Discipline, the eighth studio album by King Crimson, took many fans and critics by surprise. Drawing some comparisons to Talking Heads, the album contained several ideas and sketches that had been at least partially mapped in The League Of Gentlemen.

Beyond sharing two members of the band from the 70s, the music was a decisive break with the past. From an instrumental perspective, the interlocking twin guitars, processed through an early guitar synthesiser, went beyond mere novelty to create a rock gamelan sound. Meshed with the unconventional textures of the rhythm section, this was a spikier, pointillistic sound that owed nothing to the Mellotron-wreathed landscapes of Crimsons past.

Key Tracks: Frame By Frame, Elephant Talk, Discipline.

Beat Poets Part Two

BEAT(1982)

This album was loosely inspired by the writings of Jack Kerouac. The band brought several road-tested new numbers into the studio but were still short of material, resulting in Requiem, an acerbic improvisation veering between free jazz, electronics and storming avant-rock psychodrama. Creative tensions between Fripp and Belew came to the boil during the recording of the track, and for several tense days, actually threatened to break the group up. Looking back on the process of its making, Belew now takes the view that, “Beat was the most awful record-making experience of my life and one I would never choose to repeat.”

For Fripp, Crimson had all but died around the recording of the album. “At the time, Bill and Adrian thought that Beat was better than Discipline. For me, this is an indication of how far the band had already drifted from its original vision. The group broke up at the end of Beat… I had nothing to do with the mixing… nor did I feel able to promote it. Somehow we absorbed the fact and then kept going.”

Key Tracks: Neil And Jack And Me, Waiting Man, Requiem.

Beat Poets Part Three

THREE OF A PERFECT PAIR(1984)

Fripp noted: “The album presents two distinct sides of the band’s personality, which has caused at least as much confusion for the group as it has the public and the industry. The left side is accessible, the right side excessive.”

If the music of Discipline had fallen easily into place, and Beat had been fraught with tension, the material making up King Crimson’s third and final album of the 1980s proved to be rather more elusive and difficult to nail down than anyone in the group could have imagined, taking several aborted attempts during 1983. “We’d all like to think that our better rock groups ‘compose’,” Bill Bruford observed after its release, “but Crimson sort of scuffles for its music. It’s down there somewhere on the rehearsal room floor, and it scrabbles and gets its fingernails dirty.”

Key tracks: Three Of A Perfect Pair, Sleepless, Industry.