Pete Townshend, The Who’s songwriter and guitarist, had endured many bad days. But few as bad as the one in March 1971 when he tried to throw himself out of the tenth-floor window of a New York hotel. The reason? “Everyone in the room,” he said, “had transmogrified into huge frogs.”

That afternoon, Townshend’s manager’s assistant guided him away from the window and talked him down. Townshend claimed that what he’d experienced was an alcohol-related anxiety attack. The Who’s principal composer and conceptualist was drowning himself in Rémy Martin, and driving himself crazy trying to explain his vision for The Who’s next project, a story he called Lifehouse.

Lifehouse was set in the future, maybe 1990, said Townshend, and everyone on the planet wore suits connected by wires to a central ‘grid’, which ‘fed’ them entertainment. A roadie discovers a way of ‘feeding’ people music instead… It was going to be a movie and an album. There was just one problem: no one else had a clue what he was going on about. By the time Townshend found himself contemplating that open tenth-floor window it was debatable whether he knew any more. Something had to give.

Instead of Lifehouse, The Who went off and made the non-concept album Who’s Next. It became the best-selling record of their career so far, and turned this most dysfunctional English pop group into one of the world’s most famous rock bands. But Who’s Next wasn’t Lifehouse.

For the next two years, through Who’s Next and Quadrophenia, Townshend fought to turn more of his maddeningly complex ideas into reality and satisfy those who just wanted The Who to remain a noisy, brawling arena-rock band. It nearly destroyed the group along the way. “It was the closest we ever came to breaking up,” said lead singer Roger Daltrey.

The Who’s dilemma was apparent at the start of the 70s. In one corner was 1969’s Tommy, The Who’s ‘serious’ rock opera about a deaf, dumb and blind boy hailed as a messiah. Tommy had brought The Who back from the brink of obscurity in Britain and had also broken them in America.

In the other corner was 1970’s Live At Leeds, containing overdriven versions of their early hits Substitute and My Generation, and revved-up covers of Summertime Blues and Shakin’ All Over. This was the visceral pop that Townshend, Daltrey, bassist John Entwistle and drummer Keith Moon had played in West London pubs and clubs in the mid-60s. Which way to jump?

Tommy had made The Who, but by the end of 1970 it had become a millstone around their necks. Townshend regarded it as his mission to write something that would supplant The Who’s ‘rock opera’. Enter Lifehouse.

“In Lifehouse, humanity would survive ecological disaster by living in pod-like suits, amused and distracted by sophisticated programming delivered to them by the government,” explained Townshend. “Because of its potential to awaken the dormant masses, rock music would be banned.”

According to Townshend, the initial inspiration came from the writings of a Sufi musician Inayat Khan, who believed that there was a universal note of music, “a keynote of the chord to which we all belong”, that could transport the listener. In Lifehouse, a similar universal note would transport the population. Lifehouse also accommodated Townshend’s growing obsession with computers and synthesisers. In Lifehouse the population would be introduced to music by a roadie called Bobby, who uses high-tech equipment to devise sounds created for each of the population based on their astrological star signs. Discovering Khan’s ‘universal note’ would have dramatic consequences. “The audience keep attaining higher states,” said Townshend. “And, finally, it gets too much and they actually leave their bodies. They disappear.”

Townshend’s idea of a central ‘grid’ now sounds remarkably similar to the internet. Even Bobby’s advanced music technology wasn’t that far-fetched. In 1970, researchers were experimenting with a synthesiser that could be ‘tuned’ in to a human’s heartbeat.

But when Townshend pitched Lifehouse to the rest of the band they failed to understand. “It’ll never work,” said Daltrey. The Who’s lead singer was a practical man who’d worked on building sites and in a steelworks. “You’ll never get enough wire.” ‘Universal notes’ were all very well, but the lack of cable to connect households to the central grid was what bugged the pragmatic Daltrey.

“I’d explain Lifehouse to Roger and John and Keith, and they’d say: ‘Oh, I get it. You put these suits on and put a penny in the slot and get wanked off,’” recalled Townshend. “I’d say: ‘No, it’s much bigger than that.’ ‘Oh, I get it. You get wanked off and you get a Mars bar shoved up your bum…”

“It didn’t make any sense,” said Daltrey. “None of us could grasp it. But it did have some good ideas in it. The one I picked up on was that if we ever did find the meaning of life it would be a musical note. I thought that was a great idea.”

If Townshend felt deflated, he pushed on anyway. His first step towards Lifehouse was to stage an event at London’s Young Vic theatre. At the beginning of 1971, Universal Pictures had offered Townshend $2 million (£1.3m) for a Lifehouse movie. Or so he thought. Townshend planned to film some of the Young Vic event for use in the movie. He wanted the event to be more than just a gig and the opportunity for the band and their audience to interact.

“We want to see how far the interaction can be taken,” he explained. “I don’t seriously expect people to leave their bodies. But I think we might go further than rock concerts have gone before.”

Frank Dunlop, director of the Young Vic, was delighted to have a teenage audience in the theatre. The Who announced their Young Vic ‘happening’ at a press conference on January 13. “We shall try to induce mental and spiritual harmony through the medium of rock music,” Townshend told journalists. But not everyone was convinced. “I remember the puzzled look in Roger Daltrey’s eyes,” Frank Dunlop recalled. “I think Roger was wondering: ‘Where am I in all this?’”

On February 14 almost 1,000 Who fans filled the Young Vic. Townshend talked to them about Lifehouse, but the traditional roles of ‘band’ and ‘audience’ remained: the band played, the audience listened. After the show, Keith Moon led a bunch of groupies back to his motorhome. It was business as usual.

More Young Vic events followed. But The Who faced the same problem as before. Fans expected a show. The Who would play the new songs and then relent and play the old stuff. Townshend: “And the audience would leap about, and we’d look at one another and say: ‘Well that’s obviously where it’s at.’”

At one of the final Young Vic events, in May, Townshend’s frustration spilled over after a hippie kept shouting: “Capitalist pigs!” at him. Eventually Townshend lost patience, hauled the heckler on to the stage “and beat what shit there was left in him out of him”. A higher state of consciousness would have to wait.

Townshend’s struggle to make everyone understand Lifehouse was now compounded by shadowy dealings inside The Who’s camp. After being told that Universal Pictures wanted Lifehouse, he discovered that The Who’s co-manager, Kit Lambert, had told them they’d be making a film of Tommy instead. The Who’s deaf, dumb and blind kid was still overshadowing everything they did.

Lambert was the aristocratic son of the eminent English composer Constant Lambert. He’d helped Townshend create Tommy, and it appealed to his sense of grandeur to turn Tommy into a movie. Lifehouse just confused him.

Lambert then claimed that Universal would back both movies, while secretly planning to get Townshend’s futuristic fantasy shelved. In the meantime, he’d persuaded Townshend to start recording Lifehouse for an album at New York’s Record Plant studio. Lambert intended to produce the sessions, as he had done with Tommy. Before long, though, he was sidelined from the project. The songs were coming together, but New York’s drugs culture offered too many distractions. Lambert was using heroin, and Townshend was scared that the increasingly wayward Moon would follow suit. In the meantime, Townshend “drank bottle after bottle of brandy, probably imagining I was showing great restraint”.

When the guitarist walked into Lambert’s office and overheard his manager dismissively referring to him as “Townshend” instead of “Pete”, he cracked. Seconds later he was heading towards the open window, convinced everyone in the room had turned into frogs.

That was Townshend’s wake-up call. He was drinking – and working – too much. But Townshend was the world’s most conflicted rock star. Since 1968 he’d been following an Indian spiritual master, Meher Baba. Baba preached peace, love and a drug-free existence. It was a welcome alternative to The Who’s chaotic lifestyle, but one Townshend found difficult to fully embrace.

The rest of The Who were almost as conflicted. Roger Daltrey had no interest in narcotics and barely drank. But Entwistle and, especially, Moon embraced booze, pills and cocaine. Townshend, meanwhile, avoided cocaine and had sworn off LSD since 1968. He was, however, still drinking – and heavily. The dichotomy was not lost on him, especially when Baba disciples visited The Who on tour. “They’d walk into the room, and go ‘Jai Baba’, which means ‘victory to Baba’, and there’s broken guitars on the floor, piles of whiskey bottles, and TV sets out in the street. They just can’t equate the two things.”

“It was a hedonistic time in New York,” confirmed Chris Stamp, Lambert’s partner in managing The Who. “It was not good for getting creative with a group of people.” Stamp (who died in 2012) also became consumed by the city’s “neurotic drug culture”. Chris was the younger brother of the actor Terence Stamp, and a plain-speaking East Londoner whose level-headedness had always helped balance out Lambert’s grandiose ideas. Between them Lambert and Stamp had guided The Who to international stardom and launched their own label, Track Records. But the pair’s decline would soon impact on their clients.

Desperate to get away from Lambert, Townshend moved The Who into Olympic Studios in London, with the Stones’ engineer Glyn Johns co‑producing. But his bandmates’ lack of understanding meant that what they were creating was no longer Lifehouse.

“The whole problem with Lifehouse was that the concept was too ethereal,” protested Daltrey. “Music-wise it was some of the best songs Pete’s ever written, but the narrative wasn’t very strong.”

“Roger was ringing me up every day trying to dissuade me from doing the project,” said Townshend, “We eventually gave up and we just went back into the old mould.”

For Townshend, “the old mould” meant making the conventional album Who’s Next. But the Lifehouse ideas were still there, flitting like ghosts through the songs. Khan’s writing was referenced in Getting In Tune; and Baba’s teachings were referred to in the lyrics to Bargain (“a love song about a higher love”, said Townshend, “between master and disciple”) and more candidly in Baba O’Riley.

Who’s Next’s closing song was Won’t Get Fooled Again, a track recorded at Mick Jagger’s country pile, Stargroves. It captured all of The Who’s mad, contrary charm. One minute, Townshend was preaching revolution (‘We’ll be fighting in the streets’), the next he was pouring scorn on the idea (‘Meet the new boss, same as the old boss’). Like Baba O’Riley and the ballad Behind Blue Eyes, Won’t Get Fooled Again was among The Who’s finest work yet. But there was a problem.

“[Who’s Next] was a compromise album,” said Townshend. “I felt it was making the best of what we had at the time.” The front cover showed the band in the aftermath of urinating against a pile of concrete in a Durham colliery, some might say metaphorically pissing over Townshend’s big idea.

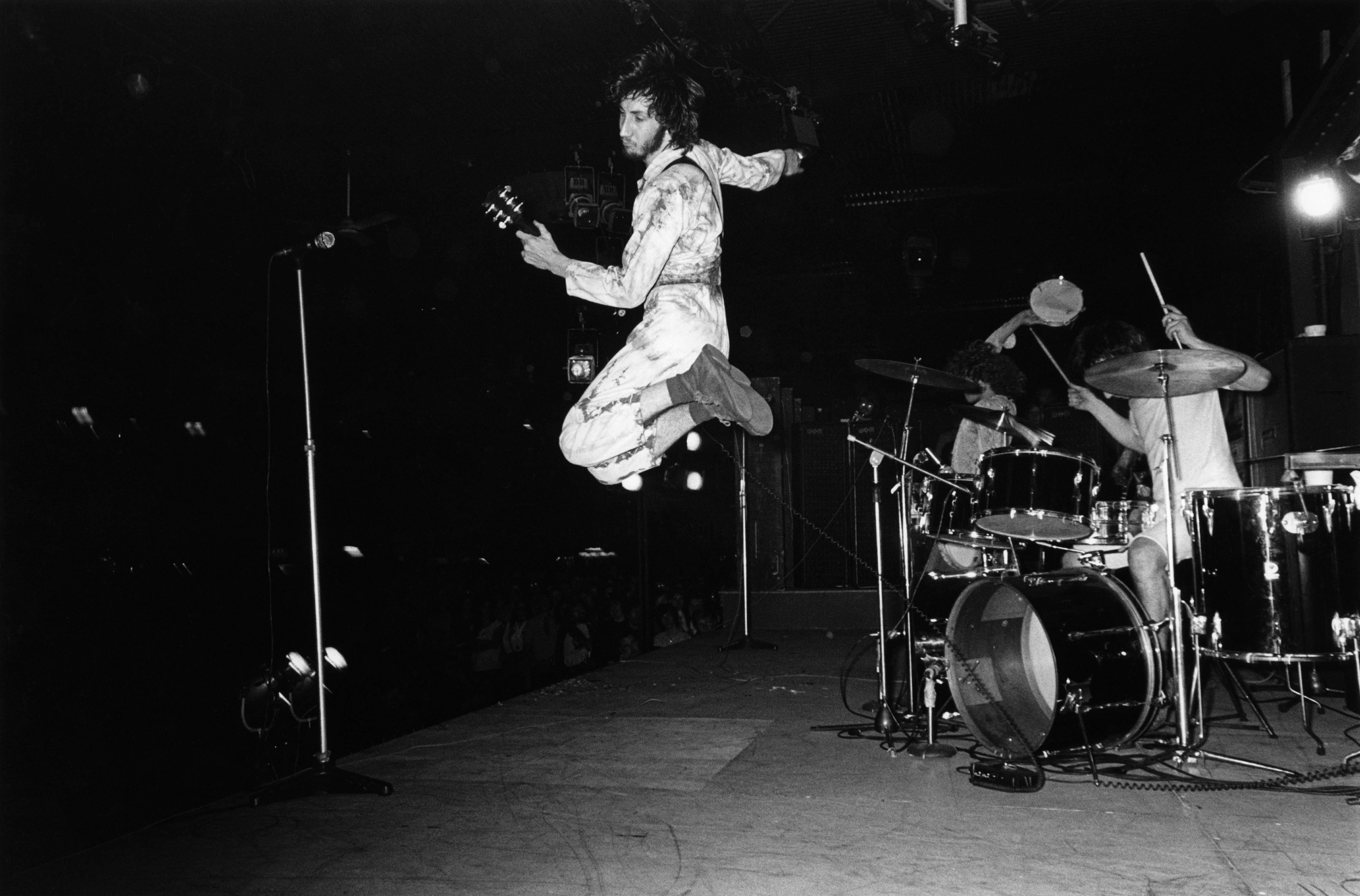

Who’s Next was released in August, and went to No.1 in Britain. Thanks to consistent airplay it reached No.4 in America. On tour in the States that summer, The Who played 18,000-seater arenas, cranking their new mini-symphonies through a £20,000 PA system. “We were the first band to play stadiums and the first band to anthemise the concert,” said Townshend. “Anthemising” was Townshend’s name for the process in which songs started quietly and grew louder and louder and louder and then stopped. What Townshend discovered was that while nobody actually left their body and started transcendentally floating, the likes of Baba O’Riley and Won’t Get Fooled Again (“Little concerts inside big concerts,” as he described them) were still capable of transporting an audience.

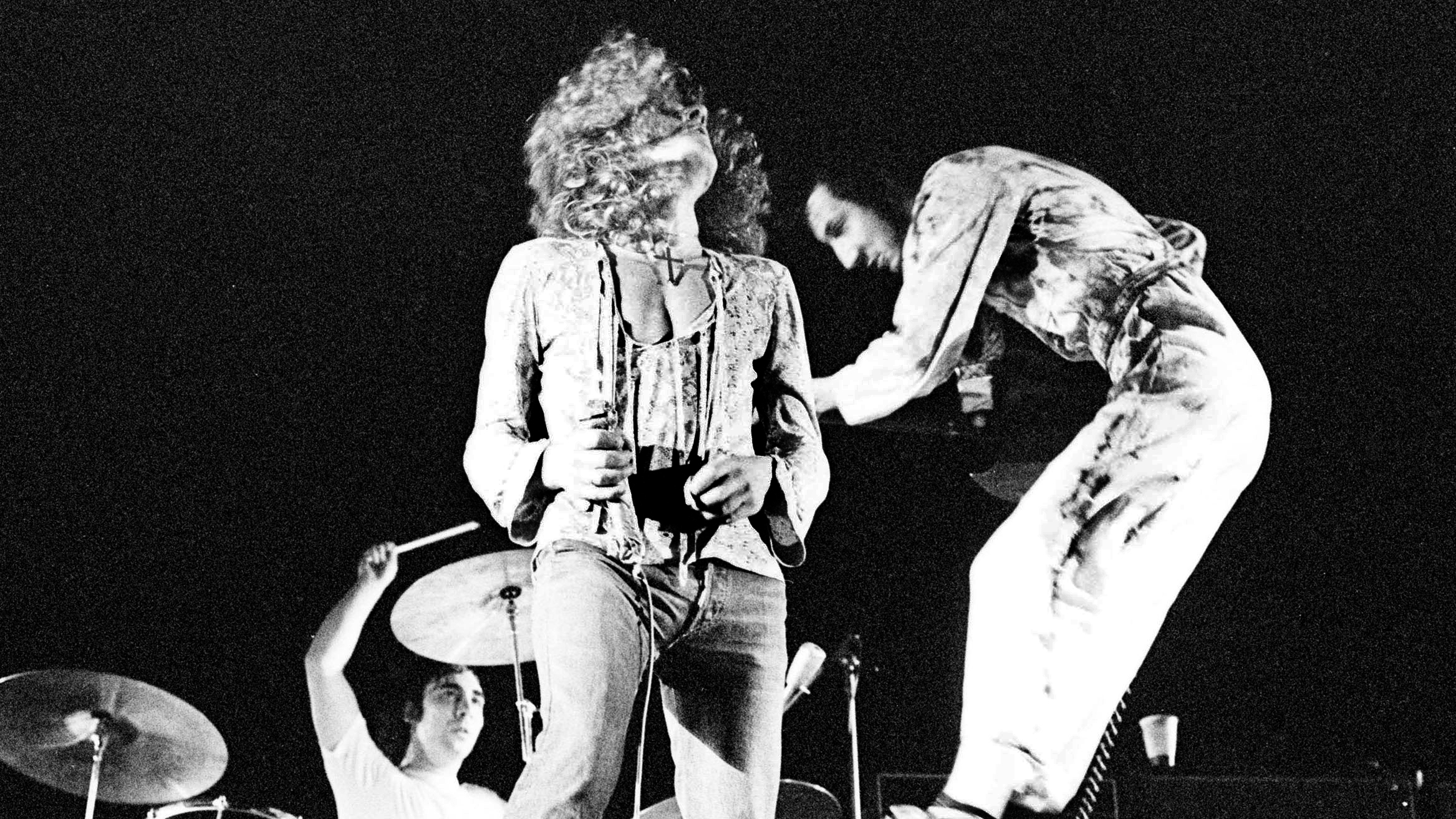

Nobody understood this better than Roger Daltrey. In the 60s, Daltrey was searching for his own identity within The Who. The band had grown out of Daltrey’s school group, but Townshend had always treated him like a junior partner. Now, with his long, flowing curls and town-crier’s voice, he looked and sounded a proper rock star. Daltrey remained sympathetic to Townshend and his highfalutin ideas. But he knew what was needed to sell those ideas to a live audience, and that Lifehouse in its original form would have been a very hard sell. “Every tangent we went off on reinforced Roger’s stand, which was that the group was perfectly alright as it was and that I shouldn’t tamper with it,” Townshend despaired.

In fact Townshend’s view was a little too simplistic. Despite the success of Who’s Next, Daltrey was far from complacent. “I wish I could put my finger on what was wrong,” he told Melody Maker. “But it is so hard to follow Tommy. It’s not dissatisfaction. I don’t know what it is.”

What Daltrey wanted was for Townshend to create music that satisfied his creative urges but that would also connect with 18,000 people in a cattle shed in the American Midwest. Something with the spirituality of Tommy and the visceral punch of My Generation, perhaps? But finding that was a challenge.

At the end of 1971 The Who were confronted with their past in the shape of Meaty Beaty Big And Bouncy, a ‘greatest hits’ collection rush-released for the American market. Townshend, never one to mince his words, declared it “The best Who album ever”. In the meantime, he’d just issued a low-key solo album, Who Came First, dedicated to Meher Baba. It included one of Lifehouse’s greatest songs, Pure And Easy, which should have been on Who’s Next.

Back in The Who, nobody seemed to know what was going on. There were now two Who movie projects under consideration. One was a documentary, Rock Is Dead, Long Live Rock, being written by the music critic Nik Cohn. So far, so good. The other was “a Utopian rock music idyll” titled Guitar Farm. The latter was the brainchild of a collective of political filmmakers called Tattooist International. Guitar Farm was set on an island where musical instruments grew, like plants, out of the ground, and where famous missing people such as Glenn Miller and Adolf Hitler had come to hide out.

“We start in January, and Pete is writing the music,” Daltrey told the press in November ’71. “We’ll get more involved as it progresses. But I don’t want to say too much about the story.”

It didn’t happen. Kit Lambert didn’t want anything standing in the way of his planned Tommy movie. His lawyers advised Tattooist International to back off, and Guitar Farm was quietly forgotten.

In January ’72 Townshend flew to India to visit Meher Baba’s grave and seek spiritual guidance. In contrast, Roger Daltrey was busy renovating his new 15th-century Sussex mansion, complete with its own trout lake and a gypsy caravan on the front lawn. Elsewhere, Keith Moon had purchased the extravagant Tara House in Chertsey, with a pub at the end of the driveway and a huge pond into which he would later drive one of his many cars. Only John Entwistle was still living modestly, in a semi-detached house in Ealing.

While working on Rock Is Dead, Townshend was suddenly struck by how eccentric and disparate the four members of the band were. Like Guitar Farm, Rock Is Dead was eventually put on hold. But Townshend came away from it with the germ of an idea all about “the four extreme characters in The Who”.

Come May, The Who were back at Olympic, trying to make the follow-up to Who’s Next. Two new songs, Join Together and Relay, were released as stop-gap singles. But the group were still searching for what Daltrey called “that elusive something”. Their search wasn’t helped by the reappearance of Tommy. So far, Townshend had stonewalled Lambert’s request to make a film of the album. But he couldn’t resist American composer/arranger Lou Reizner’s request to record Tommy with the London Symphony Orchestra. Reizner’s vision appealed to Townshend’s need to make something bigger than a simple rock album.

In desperation, he packed his bags and, joined by his wife Karen and his two young children, drove his mobile home to the South of France. The trip was meant to clear his mind, but he kept coming back to the idea of The Who’s four characters, and how that might be interpreted on an album. “I wanted a replacement for Tommy,” he later wrote in his autobiography, Who I Am. “I believed I might have one last chance to hold us together. My bandmates had almost stopped listening to me.”

His bandmates had certainly grown restless. Entwistle had released one solo album, Smash Your Head Against The Wall, in 1971. It had hardly challenged Who’s Next for sales, but he’d just finished making a follow-up, Whistle Rhymes. Daltrey, too, was considering an album of his own. Daltrey was Townshend’s biggest fan, but he was frustrated by the struggle to ‘replace’ Tommy.

Townshend realised that the best way to replace Tommy was to look back to The Who’s earliest days. In the early 1960s The Who had played to a loyal following of London mods. Early Who hits such as I Can’t Explain and My Generation had been written for the dysfunctional adolescents Townshend saw at every Who gig. The hip clothes and hairstyles were a disguise: Townshend recognised his own dysfunction in these dandyish mods.

The Who had long-since left the mods behind. Now Townshend wondered what it would be like to put himself inside the mind of one of those early fans. The character he created, Jimmy, would be a composite of the Who’s four disparate characters. The story would be called Quadrophenia.

“It was about a day or a couple of days in the life of a boy who has been abandoned by everybody – his parents, his girlfriend, his hero and his favourite pop band,” said Townshend. “It’s about a mod and his relationship to this group who go off into celestial territory, and yet take with them the four mirrors of his character; they take with them his very soul.”

Even if his bandmates didn’t grasp every nuance of the story, at least there was no grid, no wires and no musical instruments growing out of the ground…

In the summer of ’73, Townshend moved The Who into their own purpose-built studio facility, Ramport, in Battersea. There was just one problem: it wasn’t quite built. Townshend refused to wait, and arranged for The Faces’ bass player Ronnie Lane’s mobile studio to be parked outside and cables run into the half-completed room. Townshend’s enthusiasm was understandable. But Quadrophenia’s music was complex, and trying to recreate the sounds in Townshend’s head in a half-finished studio was a recipe for disaster.

Similarly disastrous were Kit Lambert’s attempts to produce the album. Lambert was often drunk, and appeared to be on the run from every heroin dealer in London. When Townshend discovered he’d been erasing tapes behind his back, he threatened to punch him and Lambert was sacked.

Townshend had been so absorbed in his work that he hadn’t realised the extent of his manager’s decline. But Daltrey had. The singer despaired of Lambert and Stamp’s behaviour and suspected the pair of financial mismanagement. Daltrey demanded an audit, and discovered that “we’d been screwed up the alley”. Track Records owed thousands of pounds, and The Who were owed even more.

Daltrey’s anger was made worse by Lambert’s refusal to release his solo album, as he was scared of losing Daltrey to a solo career. The album, called Daltrey, was a collection of ballads, mostly written by an unknown songwriter called Leo Sayer.

In 1971, Lambert and Stamp had brought in Stamp’s childhood friend Bill Curbishley to work at Track Records. Curbishley was smart, ambitious and, most importantly, clear-headed. Daltrey found an ally in Curbishley, and asked him to arrange the release of his solo album, in exchange for a percentage. Within two years, Curbishley would be managing The Who. Meanwhile, Lambert and Stamp, the men who helped shape The Who, found themselves out in the wilderness.

When Townshend discovered that Quadrophenia was due for release in October, he panicked. The songs were finished, but he had envisaged spending months finessing the quadraphonic mix. The Who were planning to perform the album with a quadraphonic sound system. They also needed to prepare backing tapes of the extra instruments and sound effects used on the album. Now, with a deadline for both the album and a tour looming, Townshend’s best-laid plans started to crumble.

While Quadrophenia was a No.2 hit in Britain and America, Townshend regarded it, like Who’s Next, as a compromise. It didn’t sound the way he or Daltrey wanted it to. Frustratingly, it still contained songs to match those on Tommy or Who’s Next. Daltrey had given the performance of a lifetime on Love Reign O’er Me, 5:15 and The Real Me.

In September The Who went into Shepperton Studios for tour rehearsals. Nobody can recall the precise circumstances that resulted in Daltrey knocking Townshend unconscious. Townshend admitted he had been putting away the brandy before he arrived at Shepperton that day. Daltrey had been waiting for hours. Tempers flared. “The last thing I wanted to do in the world was to have a fist fight with Pete Townshend,” said the singer. “Unfortunately he hit me with his guitar.”

It took a single punch from Daltrey to knock Townshend out. Eyewitnesses recall the singer standing over his bandmate’s prone body and apologising, even as the ambulance was carting him away. But with the drink, drugs, financial mismanagement and Townshend’s intransigence, it was a miracle it hadn’t happened sooner.

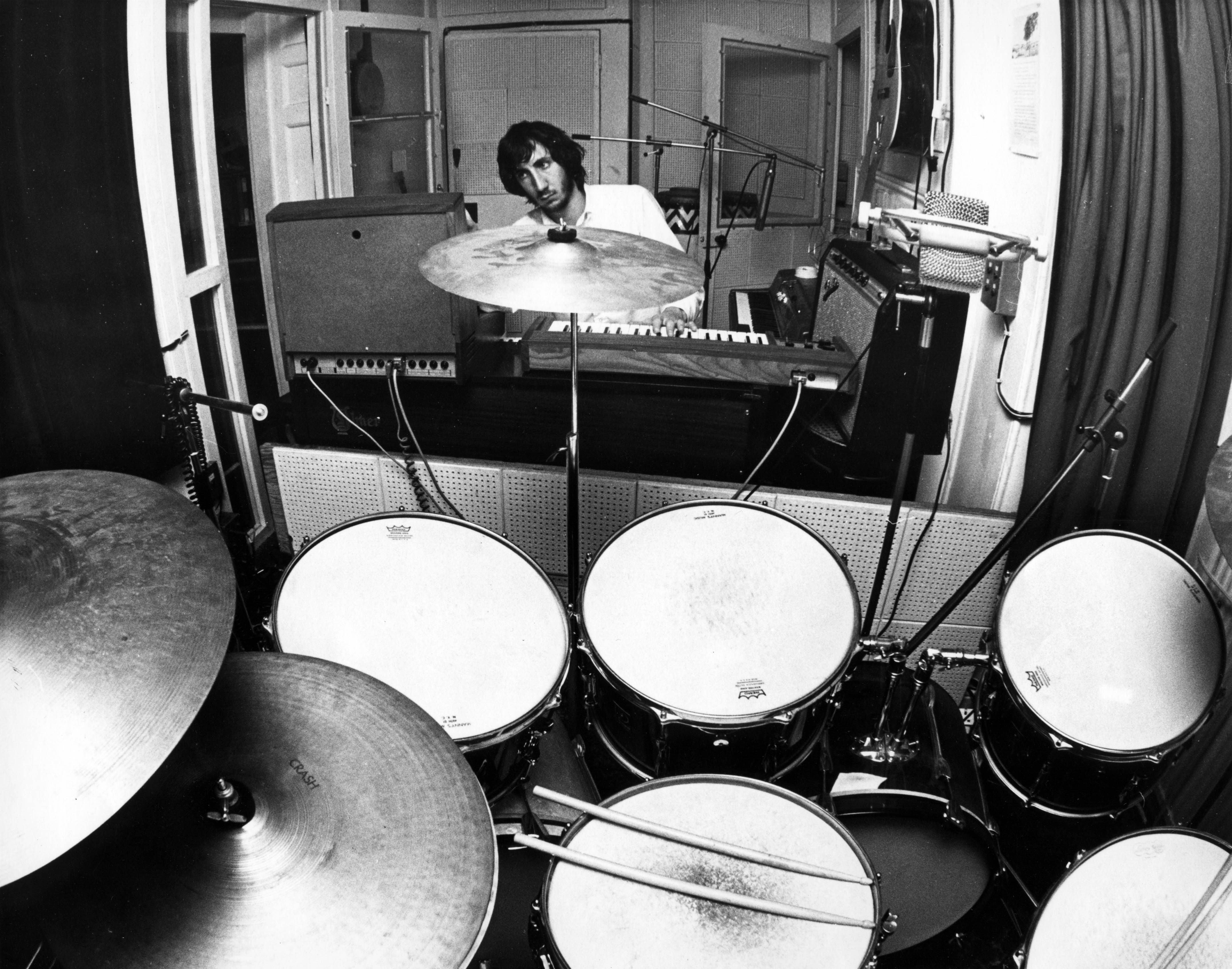

Daltrey and Townshend avoided coming to blows again, but the subsequent Who tour was fraught with problems. Once again, Townshend’s brilliant imagination had come up with something The Who couldn’t quite recreate. The average hall couldn’t accommodate all four banks of The Who’s quadraphonic speakers, Keith Moon struggled to play in time with the backing tapes needed to reproduce Quadrophenia, and the tapes themselves were equally unreliable.

At Newcastle Odeon, the tape sync for 5:15 came in 15 seconds too late. Townshend grabbed The Who’s sound engineer Bob Pridden and dragged him onto the stage. A furious Townshend then began destroying the tapes and the soundboard. The stage curtain was lowered. After 10 minutes The Who reappeared and Daltrey led them into My Generation. The Who’s angst-ridden 1965 hit single seemed like the perfect antidote to their complex and ‘unplayable’ new music.

Two months later, at the San Francisco Cow Palace, Keith Moon finally broke. Before the show the drummer had swallowed three elephant tranquilliser pellets. After slumping over his kit during Won’t Get Fooled Again, he passed out and had to be carried off stage. Instead of asking the audience if there was a doctor in the house, Townshend requested a drummer. A 19-year-old student called Scott Halpin offered his services and joined The Who for three songs. It was a very Lifehouse moment: the fan plucked from the audience that became part of the band. Perhaps this was what Townshend had been hoping for at The Young Vic?

Back in England in December, Townshend took his seat in the audience at London’s Rainbow Theatre to watch Lou Reizner’s stage production of Tommy. The cast included The Goodies’ Bill Oddie, the then Doctor Who Jon Pertwee, and Roger Daltrey in the role of Tommy. That night, for the first time, Townshend watched The Who’s lead singer as a member of the audience. He was stunned. “He projected himself into the crowd,” he said. “His technique was that of an experienced stage actor.”

A year later, Daltrey would reprise the role in the movie version of Tommy. Quadrophenia had failed to eclipse Tommy; Townshend had failed to stop Kit Lambert making his movie; and now his lead singer was in danger of becoming a film star.

Against the odds, The Who survived. But they would never attempt anything as grandiose as Lifehouse, or even Quadrophenia, again, although Townshend would revisit Lifehouse for a BBC radio drama in 1999 and would release The Lifehouse Chronicles box set a year later.

The Who have also remastered and expanded Quadrophenia to bring it closer to how they’d envisaged it in 1973.

Whether it’s Who’s Next or Quadrophenia or the music that fell between the gaps of both, The Who’s work during the troubled early 70s set a standard they would never reach again. It still sounds like Townshend is reaching for something that’s just beyond his grasp, and it still sounds as if Daltrey is dragging him back to the earth. “Pete’s a genius,” claims the singer. “But he’s bloody hard work.”

Then and now, it’s this conflict that makes The Who so special.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #185.

For more on The Who and Pete Townshed at seventy, then click on the link below.