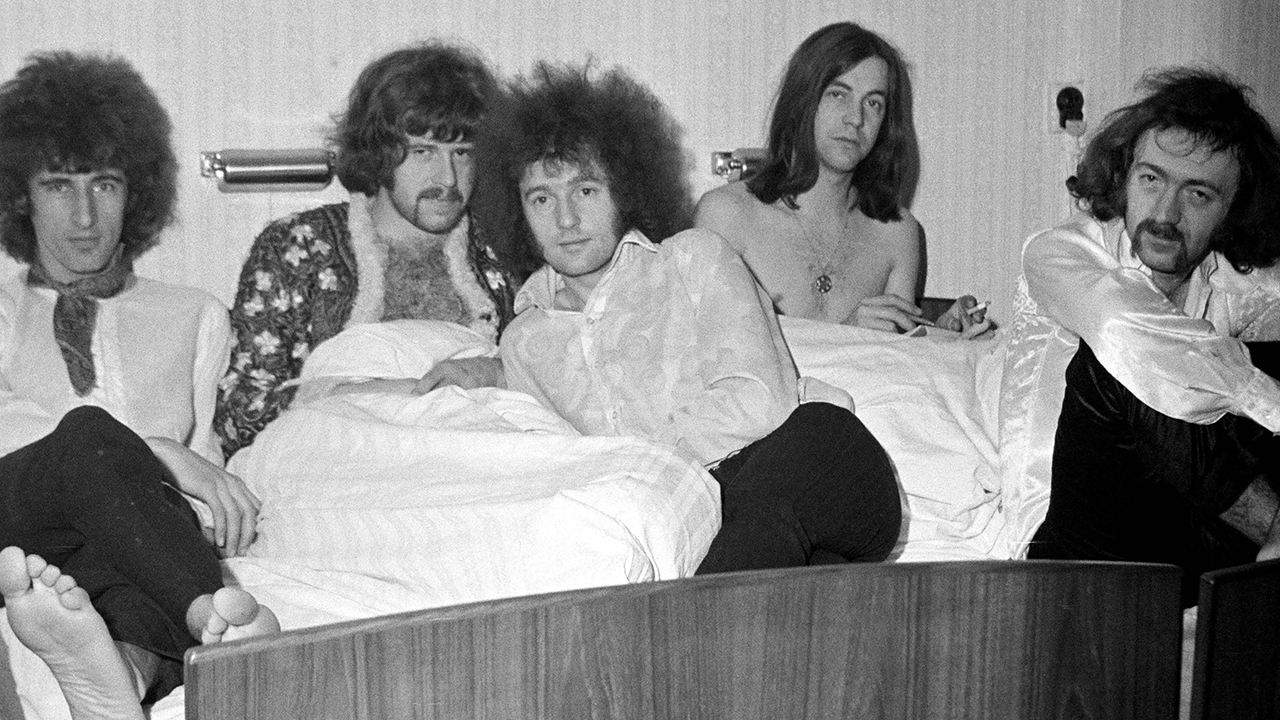

In 1968 The Pretty Things delivered what’s arguably the first rock opera in the form of their fourth album, S.F. Sorrow. Swamped with issues from all sides, they didn’t receive the acclaim they deserved, although they were always convinced of the record’s value. In 2018 guitarist Dick Taylor and late vocalist Phil May told Prog what had gone wrong five decades earlier.

“We thought we were making something special. It was to give you an experience, so you move from cradle to grave with somebody’s life – which they give you in opera all the time,” says Phil May, the singer in The Pretty Things. “In some ways, that added bitterness to the pill when it was ignored.”

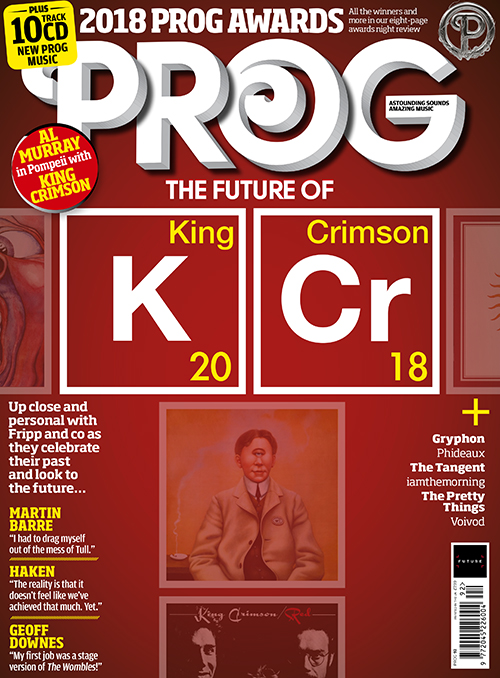

He’s discussing their fourth album, S.F. Sorrow, one of the most extraordinary British albums of the late 1960s, and one utterly beset by disaster. It was the first rock opera, yet its thunder was stolen by The Who’s Tommy. It was one of the crowning glories of English psychedelia, but it was released right after The Beatles’ White Album, just as trends started moving away from teapots-in-the-sky daydreaming to something more earthy. It was a crucial step between psychedelia and prog, but its failure put the band on their heels, just as King Crimson and Yes were starting to establish their reputations.

“We were definitely trying to push the envelope,” says May’s partner in absurdity, guitarist Dick Taylor, “which prog bands then continued to do.”

“What we were attempting was attempted again by different bands later for whatever reasons,” May adds. “We started to try to do something different. We tried to change the landscape, and a lot of prog bands came along with totally that intention. They didn’t want to be just rock bands.”

Fittingly, S.F. Sorrow’s roots were in failure. The Pretty Things’ contract with Fontana had expired after their Emotions album had been released in April 1967. That record had been both a commercial flop and an artistic failure. After making their name playing feral, unhinged R&B, they’d turned to flowery pop for Emotions, with producer Steve Rowland commissioning Sunday Night At The Palladium-style brass and strings to go on top. Freed from their contract, though, they could leave that behind.

“When we finished with Fontana, we could do what the fuck we wanted, which was to go in and do demos,” Taylor says. “That gap after leaving Fontana gave us the time to do them, and that’s what got the attention of Norman Smith.”

EMI in-house producer Smith, who’d overseen the first two Pink Floyd albums, was EMI’s champion of the underground, and he persuaded the label to sign The Pretty Things. “They certainly didn’t pay a fortune for us,” May says. “The signing-on fee was wiped out in debt anyway. And they made us pay for the printing of the story of S.F. Sorrow, and that was another £700. So we were already out of budget and in debt by the time we started making S.F. Sorrow.”

The story May refers to was a printed sheet that came with the album, telling the life story of Sebastian F. Sorrow, the album’s protagonist. There’s no need to get bogged down with that here because, as with most rock operas, the story is incomprehensible anyway.

When Tommy came out it was presented so well that everyone knew it was a rock opera. Ours, from six months earlier, was just a Pretty Things record

Phil May

The band didn’t want to make a conventional album of 14 unrelated songs. “We wanted to make a piece of music that hung together, so it was one piece made up of different elements,” May says. “I was writing the story as the songs were written. And the story wasn’t complete when recording began. The music drove the story and the story drove the music, when it was necessary. When there was a gap in the narrative and a character was created – Baron Saturday – that drove the need for Baron Saturday Meets S.F. Sorrow. It really did evolve on the studio floor.”

The group recorded out of hours at Abbey Road, using downtime – which meant they had months to work, getting every element just so. They used unusual instrumentation (“The Tibetan drum set the tone for Death,” May says, a remark so redolent of high psychedelia it sounds like a joke); they raided EMI’s stores for things to make music with such as Mellotrons and Ringo Starr’s drum kit. When nothing in existence created the required sound, they invented it. “My father and I made the little twangly instrument, kind of like a dulcimer, which is on Death and a couple other things,” Taylor says.

All the while, Smith was cajoling and encouraging them. “It had to be improvisatory,” Taylor reflects, “and what was great about Norman was that he’d take what might have been a small idea and turn it into something solid.”

Gradually, the EMI engineers – whom Taylor and May call “the boffins” – got onside too. “They really got caught up in this pushing of the technological envelope,” May says. “There was a fantastic sense that we were doing something at all levels. Still, The Pretty Things’ unconventional working practises caused occasional problems.

“At Norman’s funeral [in 2008], one of the boffins came asked if I’d heard that one of his colleagues had nearly got divorced over S.F. Sorrow,” May says. “He was a nine-to-five bloke and he started coming home at one or two in the morning because he was working on S.F. Sorrow – his wife was convinced he was having an affair.”

As might be expected, The Pretty Things embraced the times. They dressed the part, though May remembers the beads and bells having an unexpected side effect on keyboard player Jon Povey. “You could hear him coming down the road about 10 minutes beforehand, because all his bells made such a fucking racket.”

And Taylor remembers that in 1969, when they made an unlikely appearance in the Norman Wisdom comedy What’s Good For The Goose, “Povey’s girlfriend made all these clothes for us. Jesus, they were awful. They were such crap. But all the people in the film really liked them. So we did quite a good trade swapping them out.”

Though Taylor was more sceptical, May embraced LSD enthusiastically. “Acid changed my life,” he says. “I saw things in a completely different way. The actual visual experience of being on a trip was stimulating. I found I could control what was going on, to a certain point. I would turn taps on and blood would come out. You’d wash your face and you’d got blood all over it – but you knew you hadn’t.

“You could go back to the bar and talk to somebody and you weren’t covered in blood, but you’d experience it as if you were. Or you’d watch somebody’s head changing shape as you were talking to them. It was like a sharpening of the imagination for me. I don’t think S.F. Sorrow would have been impossible without it, but there’s a lot of acid in it, in the imagery.”

By September 1968, recording was finished. The Pretty Things had created something remarkable across 13 tracks: a life story told in astounding music which ebbed and flowed, and could be pastoral (The Journey) or fearsome (Old Man Going). The world’s first rock opera was complete.

In December 1968 it came out and… nothing happened. The band didn’t feel confident enough about recreating it live to go out and play it. There was one show at the Middle Earth club in London, where they decided to mime to a playback of the record. Legend holds it was a disaster because everyone involved, including the sound engineer responsible for playing the tracks, was tripping – but Taylor disputes that. “I certainly didn’t take acid!” he says. “There were technical hiccups because you couldn’t just press a button on the computer. You had to stick the needle on the album. If only we’d just decided to buckle down and play it.”

Worse yet, EMI offered no support. “It was a kick in the balls,” May says. “It’s one thing to let us make the bloody thing, but then all they gave us was little quarter-inch adverts saying, ‘The new album by The Pretty Things’ – nothing about the story, nothing about the narrative. When Tommy came out, everybody was so keen because it was presented so well that everyone knew what it was: it was a rock opera. Ours, from six months earlier, was just a Pretty Things record.”

I have to regard it as a success, because it was an artistic success

Dick Taylor

EMI didn’t even release the record in the US; so the band’s manager, Steve O’Rourke, had to tour American labels, touting it round, only to discover no one wanted it because it had been promised elsewhere by EMI. “This was behind the scenes, but Berry Gordy had apparently said to EMI, ‘If you want to keep Tamla Motown stuff coming through you, we want S.F. Sorrow,’” May says. “So in the end Steve was wasting his time. Although we didn’t know it, we were going to be given as

a present to Tamla Motown.”

Motown released it on its new rock subsidiary, Rare Earth – several months after Tommy came out in the States. “We got slaughtered,” May says. “Daltrey and Townshend had been saying to me, ‘For fuck’s sake, what are you doing? You’ve got to come out in America! We’re coming out in a few weeks!’ They were quite concerned – whatever Pete’s said since – that it would have been wrong for Tommy to come out before us in America. And they were right. EMI were our parents and they’d given the baby away with absolutely no control or say in what happens. We were sold out.”

Taylor left The Pretty Things in the aftermath – “I had made a record I was really proud of and happy with; maybe it was time to go on to other stuff” – rejoining in 1978. May soldiered on, making another fascinating proto-prog song suite, Parachute, in 1970, before reconfiguring as a hard rock band. Now, with S.F. Sorrow rehabilitated as one of the great British albums of the late 1960s, both May and Taylor have set aside their disappointments.

“I have to regard it as a success, because it was an artistic success,” Taylor says.

“It’s the most important Pretty Things record, for me anyway,” May adds.

“For me, too,” confirms Taylor.

Oh, you Pretty Things. The greatest group who ever managed to shrug off greatness.