Van Halen: how the wheels came off and the bad feeling that fuelled 1984

Fighting with the Clash, recording with Jacko, swapping guitars for synths – how Van Halen made their bestselling album

The singer, on one of his many loony adventures, is lost in the Amazon rainforest weeks before the biggest gig the band will ever play. The guitarist is threatening to burn the master tapes of the new album, which is taking considerably longer than the usual five days to record. Drunken insults will be exchanged with The Clash at a festival supposedly celebrating brotherly love and togetherness. Yet, to the outside world, things appear more tranquil.

Here are Van Halen, seemingly loved and loathed in equal measure; a roving gang of pranksters united in their desire to have fun in a world that takes itself too seriously – “like a buncha of gypsies yukking it up in the Foreign Legion,” as the singer would say. And, as recent recipients of the highest fee ever paid to any performer – $1.5m for a drunken two-hour ramble through their best known songs that lands them in the Guinness Book of World Records – they have every reason to feel relaxed about the state of their world.

But now, in the summer of 1983, the 70s – and the loose life that decade had promised – seem finally, and belatedly, to be over. Suddenly the stakes have been raised. With MTV in the ascendancy, the record company now wants bona fide hits that will tear up the pop charts. So, it was just as well that here, on 1984 – their final full-length album with original vocalist, David Lee Roth – Van Halen knew they had something big. All they had to do was make it through to the fateful year that adorned their work-in-progress.

Hidden high in the Hollywood Hills, just a few miles from the more well-known rock’n’roll neighbourhood of Laurel Canyon, you will find Coldwater Canyon. Of the many Los Angeles canyons this was the one where the really wealthy preferred to hide away from the noise of Hollywood. While Neil Young, Frank Zappa and other 60s icons pitched up in Laurel Canyon, the better-off movie stars – Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston – retreated to Coldwater.

As the road snakes up towards Studio City from Mulholland Drive, even the most eagle-eyed driver could miss a narrow passage that slips away to the right at one particular sharp bend. It quickly disappears into a tunnel of overhanging leaves and branches. Here, in 1983, Eddie Van Halen would build a rudimentary 16-track studio, in an attempt to wrest control of the band that bore his family name from the guiding influence of David Lee Roth, the songwriting partner he would soon be comparing to infamous dictators like Idi Amin and Colonel Gaddafi.

While other people went looking for a home, Eddie – aka “Ed Van Halen, the Unabomber,” as David Lee Roth would call him – sought a hideaway. In the years since 1998’s poorly-received Van Halen III, there had been tales of fans making pilgrimages to that little road that slopes off Coldwater Canyon Avenue in search of nothing more than a security camera that might convey some message – PLEASE RELEASE SOME NEW MUSIC – in the hope that the reclusive guitarist might see that there is still a world watching on the other side of the gate.

Such a lack of activity, of course, is understandable amongst men of a certain age – those who have seen better days and who perhaps still remain shell-shocked by the slow death of the record industry as they knew it. Yet, the waning of Van Halen also provided one big clue to their massive success in the late 70s and early 80s: namely, that they existed as the embodiment of an insatiable desire to live and play fast and loose.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

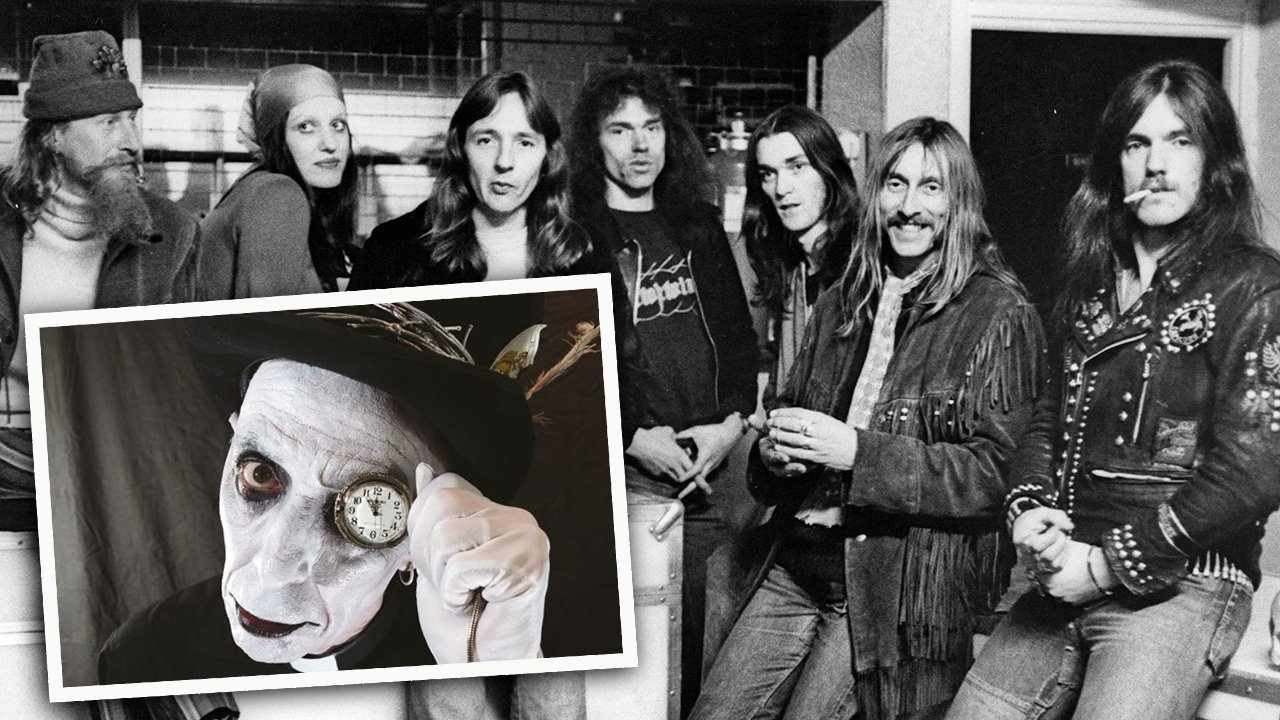

Even the cover of 1984 – adorned with the image of a mischievous sprite – suggested that this was a band that might experience some problems with the ageing process. “I hate the word maturing,” Roth had told Rolling Stone in 1978. “I don’t like the word evolving, or any of that bullshit. The idea is to keep it as simplistic, as innocent, as unassuming and as stupid as possible.”

It was an attitude that meshed perfectly with Van Halen’s modus operandi in the years 1977- 1982, with albums sometimes cut in mere days and – at most – weeks. In their initial demo sessions for Warners, their engineer Donn Landee recalled, the band cut “28 songs in two hours.”

In an era when bands would often find themselves trapped in the studio, tinkering endlessly, producer Ted Templeman made sure his charges came to the studio already primed to lay down new material with minimum fuss.

“All I have do,” he once said, “is stick a microphone in front of them.”

By the time of 1982’s Diver Down album, however, Eddie had decided that there had to be an end to Templeman and Roth’s fast’n’dirty approach to studio work. The haste with which that album was conceived and recorded was illustrated by the fact that it cost less to make than their debut album.

A sideways take on that album by US journalist Dave Queen, written in 2005, is not far short of how it was probably seen by Eddie: “Diver Down, where pothead singer David Lee Roth took over, included five cover versions – with its additional fragments, sketches, and impenetrable arcana, Diver Down is like an ‘unofficial’ Fall release or [The Beach Boys’] Smiley Smile. To appease the guitarist, a detail of his famous adhesive taped guitar was the cover art.”

The real bugbear, though, was its cover of Martha And The Vandellas’ Dancing In The Street, a song chosen by self-confessed Motown freak, David Lee Roth. The song gnawed away at Eddie’s sense of creative freedom, made worse by the feeling that Templeman and Roth had “stolen” his original piece of music (the song’s inventive and pulsating Minimoog riff) to use on yet another cover tune.

“I fucking hated that song. I never wanted to do it. That was the reason I decided to build my own studio.” Roth, though, saw it all differently. The fact was that any cover tune they did, in his opinion, they owned –“Van Halenized” – in their own peculiar fashion. “A song’s a song,” he told journalist Steve Rosen in 1980. “It’s the same thing as stealing hubcaps – pretty soon they’re on your car.”

T he story of 1984 – or MCMLXXXIV/ 1984 to give it the title that appears on the sleeve – really begins on a spring day in 1982, shortly after the release of Diver Down, when Eddie showed up at Frank Zappa’s house in Laurel Canyon to meet the man who had recently thanked him for “reinventing” the guitar. It would turn out to be a more auspicious occasion than he could have ever imagined, as he got a close look at the well-kitted studio in the basement, which further emboldened him to begin building his own studio.

In Zappa’s studio, the two guitarists – along with Steve Vai, a Zappa band member at the time – jammed some tunes, as the 12-year old Dweezil Zappa looked on, amazed that Eddie had turned up wearing the jump suit he was pictured with on the sleeve of Van Halen’s 1980 album, Women And Children First.

As it happened, Dweezil had been learning some choice Van Halen licks himself, courtesy of Steve Vai, which he practiced with his band, Fred Zeppelin. Seeing as Van Halen weren’t due to go out on tour until July, Eddie ended up spending the best part of a month – during May and June ’82 – driving over to the “Utility Muffin Research Kitchen” (as Zappa’s studio was known) with Van Halen’s engineer Donn Landee, to produce a single titled My Mother Is A Space Cadet for Dweezil and his little band of non-musicians.

“We couldn’t play,” Dweezil recalled, “and Eddie couldn’t figure out a way to get us to play together in time – so he just shouted ‘Go’, as if he was starting a kart race.”

As was the case with Eddie’s previous non-band work, it was kept low-key, and the production would be credited to “The Vards”, a pseudonym chosen by the guitarist and Donn Landee. The presence of Landee was significant in everything that would unfold over the next year or so, as he stood shoulder to shoulder with Eddie in his determination to make the new record his way in a studio they would build together.

The idea, Alex Van Halen said, was to build “a clubhouse where he could experiment at any time and where there wasn’t a clock running. The record company wasn’t thrilled about the idea, because they always think that bands are a bunch of drug addicts who need a babysitter. But we had the clout to do it.”

Asked some time later if the studio, which would be named 5150, represented a new phase of Van Halen, Eddie said that it was more like “Phase One of Donn and Ed. Donn and I were very involved in this record. We almost took control, to a point, because it was done here in our studio, and we knew what we wanted. We weren’t about to let the album be puked out in any way – especially since it was done here.”

With Landee back in Los Angeles assembling gear for the studio – including an old 16-track console about to be thrown out by United Western Studios that had been used on sessions by the likes of The Beach Boys and The Mamas And The Papas – Van Halen took to the road in July 1982, hitting Atlanta, Georgia for the first show of a scheduled 90-date jaunt that would finish in mid-December in Jacksonville, Florida, before swerving down to South America in the New Year.

Eddie’s first – and probably unintended – blow against Roth, however, occurred during a tour break in October, when he found himself entertaining Michael Jackson and his producer Quincy Jones, who had turned up at his house in the hope that they could persuade him to play on Beat It, a driving guitar tune they wanted to record for Jackson’s new album, Thriller.

It was conceived as something along the lines of My Sharona, a huge hit for The Knack in 1979. As he banged out a rhythm on one of Eddie’s guitar cases, Jackson sang the tune to give the guitarist an idea of what they had in mind. Eddie agreed to do it, but insisted on bringing his own equipment and Donn Landee – it was the only way he would get his sound.

In the surroundings of Westlake Studio in Santa Monica, Van Halen would soon be knocking back a few beers thoughtfully provided by Quincy Jones, who figured it would help the guitarist loosen up. After listening to the backing track a to get a feel for the song, all Jones said was, “Okay, do your thing.” The guitarist let rip on a couple of takes, which were so loud that the session engineer, Bruce Swedian, left the studio covering his ears, leaving Donn Landee to man the board.

On the final run through, as Eddie was playing the last notes of the solo – which attain the whizz-bang of a firework – one of the studio monitors blew up and caught fire. As Quincy Jones’s song-writing partner Rod Temperton recalled, the people at the session could only look on in amazement at the flaming speaker, as if it was some kind of omen: “We were all there looking at this, thinking, ‘This must really be something!’” It was something – but also something the rest of Van Halen didn’t want to hear.

Some five months later, David Lee Roth had just returned from a six-week trip through the Amazon, during which he and his bodyguard Ed Anderson – lost and out of contact – were reduced to improvising an existence as they drifted from one nowhere to the next.

“A million miles up the dead-empty Amazon river,” Roth recalled in his autobiography, “it’s like every book you ever read. Ed’s making an omelette out of a can of what we think is Spam but in Portuguese is dog food. There was no picture [on the can]. We’re shopping up stuff in open-air markets, this is total pirateville.”

Roth could have had no idea that the press would, in a matter of weeks, be reporting that he had vanished without a trace. British tabloid The Sun adopted a gleeful tone in breaking the news on March 3: “Good news for music lovers everywhere. David Lee Roth, the ridiculously macho singer with heavy metal band Van Halen, has been lost up the Amazon!”

But, back in Los Angeles – musing on his good fortune in not actually being dead – a radio blaring from a nearby car delivered a bolt-like shock.

“The new Michael Jackson song, Beat It, came on,” Dave recalled later. “I heard the guitar solo, and thought, now that sounds familiar. Somebody’s ripping off Ed Van Halen’s licks.”

“Believe it or not,” Eddie told Guitar World in 1990, “I did the Michael Jackson thing ’cause I figured nobody’d know. The band for one – Roth and my brother and Mike – they always hated me doing things outside of Van Halen. I just said ‘Fuck, I’ll do it, and no one will ever know.’ So then it comes out and it’s song of the year and everything.”

Roth’s return from the Amazon was just in time to prepare for a giant outdoor show Van Halen were co-headlining in San Bernardino County, California. The Us festival, styling itself as a latter-day Woodstock, had been named “us” as in ‘we’ – not US, or “United States.”

They were, though, only one of three headline acts appearing at the three-day festival – the others being David Bowie and The Clash, who had been riding high in the States on the heels of the previous year’s Combat Rock, a Top Ten album in the US.

In a series of press conferences to publicise the festival, where he declared himself “Jah Roth”, Dave bemoaned the absence of Culture Club from the bill, but spoke admiringly of all the money the promoters were pushing his way. Talk of the money, though, only served to alert The Clash to the fact that they – with their guaranteed $500,000 cheque – had been valued at just half the price of Van Halen. With a heavy media operation talking up the neo-hippie “us generation” piffle of the organisers – led by Apple computer co-founder, Steve Wozniak – all of a sudden there seemed to be just a whiff of discord in the air.

“You are going to be part of an event so big, so different it will begin a whole new chapter in the history of live music,” the Us promo materials ran: “We will be joining together in a celebration that will mark the end of the ‘me’ decade and the beginning of the ‘us’ decade.”

But as the pseudonymous Laura Canyon later reported in Kerrang!, what was going on was somewhat at odds with the ethos of “sharing” and “working together”. “Yes, there were acrobats. There were hot-air balloons and computer displays in giant tents dotted around the grounds. But you’d be pushing it to call it a festival. For that matter you’d be pushing it to call it ‘us’, what with the acts divided from the fans and each other, the police and the punters totally split… and each of the three days divided by the genre of music, with tickets sold separately as opposed to as an overall event.”

Stuck in the “95-degree heat, dust and humidity” of the near-desert location, as the Los Angeles Times reported, agitated fans broke into sporadic fighting. “There was plenty of drug usage and scattered violence… and one death from an early morning fight in a parking lot.”

But of all the bands on the bill, it was The Clash who were torn – mad with rage, on the one hand, that they were being paid less than Van Halen, yet, on the other hand, acutely aware that now the word was out about who was being paid what, they could look greedy regardless.

So, Clash spokesman Kosmo Vinyl leapt into action, intent on making sure all this money was seen as nothing to do with them. Bernie Rhodes, manager of The Clash, also told press gatherings that they were asking the organisers to give a proportion to good causes. “We’re trying to get Mr Wozniak, who started this whole thing off in the name of money, to put some money back into California. With the figure of $18m being spent, we figure he could give 10% of that to some organisation.”

In the days and weeks leading up to Memorial Day weekend, Van Halen’s fee had initially been one million dollars, but as soon as David Bowie reputedly asked for a million-plus, the figure now due to Van Halen immediately rose to $1.5m without any effort on their part – simply due the guileless Wozniak agreeing to a clause in their contract that guaranteed they would be the top paid performer at the event. “We never asked for the money,” Eddie Van Halen said later of the $1.5m: “they offered it."

Amidst all this, Kosmo Vinyl – “the loudmouth The Clash keep on their payroll to rile things up when their energies flag,” Record magazine’s John Mendelsohn noted in his dispatches from the event – was caught muttering disparagingly about Van Halen and their “hamburger music”. Roth, though, was a dab hand at the verbal volleyball himself, once declaring that life was best treated “as if it was the Charge Of The Light Brigade – even if you are only going to brush your teeth.”

So, he merely returned Kosmo’s ball with added swerve, damning The Clash with faint praise. “Look, I love The Clash,” Roth told the assembled press backstage. “I love Should I Stay Or Should I Go… mostly because I loved Mitch Ryder’s Little Latin Lupe Lu all those years ago. But, I fully understand The Clash’s position. They’re trying to effect some cultural change, and it’s tough – they’ve got a new drummer to break in, man. They’ve got their hands full – you know what I’m sayin’?”

After threatening to walk out on the eve of their show, The Clash relented. Bernie Rhodes told the assembled press that “the people out there want us to play. Besides, if we didn’t play, Van Halen would call us communists.”

The Clash’s protests about money not being used to support charitable causes and local bands were, in the words of biographer Marcus Gray, “suspicious – given that they had specifically recruited a drummer for the gig, after being offered half a million dollars, and only began complaining after they discovered Van Halen were being paid more.” Guitarist Mick Jones even admitted later that the band “all knew that we were just doing it for the money.”

When the The Clash took to the stage with a slew of insults Strummer directed at the audience it was as if they hadn’t yet reconciled themselves to the fact that they were still there. “We’re here in the capital of the decadent US of A,” he shouted.

It was a performance that ended with scuffles onstage and recriminations off; between members of The Clash’s entourage and the festival organisers, and between the Joe Strummer and Mick Jones of the Clash, who were now barely on speaking terms with each other.

“Unfortunately,” John Mendelssohn wrote, “no one was hurt.” It was to be Mick Jones’s last performance with the band. On the day of the gig, the Los Angeles Times reported that Van Halen’s half-acre backstage area – entered via a pathway signposted “No virgins, Journey fans or sheep allowed on trail” – had been set up for a huge party for 500 guests who helped themselves to “strawberries the size of baseballs,” and “barrels of iced-down beer scattered around the enclosure."

Onstage, in between hearty slugs taken from a bottle that was passed between Mike Anthony Roth and one of his two bodyguards (now dressed as a waiter – appearing onstage between songs with a tray of Jack Daniel’s whiskey), the singer addressed the audience: “I wanna take the time to say that this is real whiskey here. The only people who put iced tea in Jack Daniel’s bottles is The Clash, baby!”

San Bernardino County Sheriff, Floyd Tidwell, whose officers policed the event, afterwards accused Roth of inciting violence by purposefully stopping the band’s performance mid-song on a number of occasions to regale the audience with reports of their own mischief, and at one point yelling, “Let’s get the cops!”

“More people have been arrested today alone than the entire weekend last year,” Roth exclaimed to riotous applause near the beginning of the show. “You are a bunch of rowdy motherfuckers!”

In the following days, amidst the wreckage of the deserted site, a disgusted Sheriff Tidwell told the assembled press that “there are some people I’d be happy never to see back in this County again – Van Halen, for example.”

With sessions for the 1984 album having begun at Eddie’s new studio the month before the Us Festival, in April, Roth and Ted Templeman, in particular, had to adjust to new recording conditions, and a new attitude to time and work. The first song to be recorded at the studio was Jump, a song that Eddie had been trying to get the band to record for a couple of years. Eventually, he had to forge ahead on his own.

“I put it down with a Linn drum machine, but when I played it for the rest of the guys in the band they said, ‘Look, Edward, you’re a guitar hero. Don’t stretch yourself too thin. Don’t start playing other instruments.’”

When they finally caved in, the song was duly recut by the whole band in a single take. With the instrumental track on a cassette tape, Roth left to work on the lyrics and vocal melody in his own peculiar fashion – which just happened to involve being driven around the Los Angeles canyons and along the Coast Highway by Larry Hostler, his roadie.

“We get into the 1951 low-rider Mercury painted bright orange and red with a white pin-stripe down the middle, Larry drives and I sit in the back… and I write the songs. We play the tape over and over again on the stereo and about every hour-and-a-half I lean over and go, Say, Lar, what d’you think of this?”

Jump was, in its sentiments at least, squarely in keeping with the stress Roth placed on being in the moment. But, more than that, the song worked because the words and the sentiment actually match the feel of the music. The bridge section in particular, with Eddie playing a tastefully chosen guitar lick and Alex complementing him on cymbals, actually give the sense, like the title of the song itself, of becoming groundless, lifted up by a gust of air.

Backstage at the Us Festival, in late May 1983, David Lee Roth told MTV that the band had already been in and out of the studio. “We’ve got the singles down, and the rest of it is coming along quite well.” When asked about the release date and title, however, he admitted, “I haven’t the vaguest idea.” At that stage, the singles were Jump, Panama and Hot For Teacher. The album’s fourth single, I’ll Wait, existed in a state of limbo until a few weeks before the album was mastered in October 1983.

After the Memorial Day weekend shebang, there continued to be further interruptions to the 1984 sessions. Roth split for a holiday in Mexico, and Eddie and his wife, actress Valerie Bertinelli, moved into a Malibu beach house they had rented for a couple of months.

During days of experimentation – and much to the later horror of the owner of the house, the schmaltzy composer, Marvin Hamlisch – Eddie all but destroyed a white grand piano that came as part of the rental deal. Taking a saw to it, and stuffing its insides with a variety of kitchen implements, he recorded hours of John Cage style “piano abuse”.

Although none of this has ever really seen the light of day – aside from a one-minute snatch on 1996’s Balance album – Eddie enjoyed pulling out the tapes and playing them to bemused journalists who interviewed him during the 1984 tour, if only to show how “fucked-up” he really was when given free reign.

But whatever was going on there in Malibu, and back at the studio in Coldwater Canyon, it began to test Roth’s patience, especially when it emerged that Eddie and Donn Landee had seemingly put the album on hold to record incidental music for a TV movie that Eddie’s wife was starring in. At times, Roth later wrote, it descended into “the type of ludicrous behaviour where I’m sitting with the producer in one studio in Hollywood, while Ed and the engineer are in another studio.”

Eddie and Donn Landee would be “working all night, not getting up during the day,” Roth said, and “threatening to burn the master tapes” if he and Templeman didn’t quit trying to obtain some of them to work on at another location. They found themselves hanging around outside 5150 “for four and five days in a row, waiting for Ed to pick up the phone in his bedroom, knowing he was in there but wouldn’t pick up.”

That was the beauty of the new studio set-up for Eddie: it enabled him, at a stroke, to side-line the disciplinarian Templeman – a self-declared proponent of “Nazi” working methods, and triumphant survivor of studio battles with such hard-headed and “difficult” artists as Van Morrison and Captain Beefheart.

“Ted sure didn’t like working at 5150,” Eddie said. “He thought I’d just throw him out if I didn’t want to hear what he had to say.”

There is, of course, not a hint of such discord on the album itself.

Opening with the unexpected sound of a warm electronic swell, 1984 seemed to herald the arrival of some new mutant, synth-driven Van Halen. But the truth was that the synths had taken outings on the previous two Van Halen albums, as well, and would likely have featured more had Eddie gotten his way earlier. The short instrumental title track and Jump follow in the footsteps of that weird time-fuck drone, Sunday Afternoon In The Park, from 1981’s Fair Warning, one of two “synth” tunes on that album, and was followed by another two on the next year’s Diver Down, featuring both Eddie (Dancing In The Street) and David Lee Roth (Intruder) on synthesiser.

The surprise on 1984 was it seemed to underline the fact that the synths were here to stay, especially after the global success of Jump propelled the album to sales of eight million units in the first 10 months of release, thereby seeming to vindicate Eddie’s ideas about what was good for the band. The other synth tune, I’ll Wait, with its low and rather nasty sounding bass notes, had a feel not a million miles from Madonna’s Like A Virgin (a record produced by Roth’s mate, Chic guitarist Nile Rodgers, and released a year later). But as with Jump, it didn’t generate much enthusiasm amongst the band.

“Donn and I felt very strongly about it,” Eddie told Steve Rosen. “No one else did, so we put it down ourselves. They [the band and Ted] heard it again and said, ‘Uh, what’s that?”

With the instrumental track in place, Roth still couldn’t find inspiration for a lyric. With a mid-September deadline for mixing the finished tracks looming, Templeman called in ex-Doobie Brothers singer Michael McDonald to help rescue the song.

“The track was cut and they were kind of stymied on the lyric,” he recalls. “I got together with David in Ted’s office, and I had put some ideas down. I went over them with him and he seemed to like them. He may have made some changes at that point, I’m not sure.”

It turned out to be a good day’s work for McDonald, as I’ll Wait would be one of four US hits culled from the album, which by that time was on its way to becoming one of the biggest-selling albums of the 1980s.

“It’s probably one of the more lucrative things I have ever done in my entire career,” McDonald said. “As the Doobies, we did great with records. We had platinum records, but Van Halen was the inception of mega-platinum record sales.”

More naturally Rothian in flavour, however, were the likes of Hot For Teacher, Panama and Drop Dead Legs. A little known fact about Van Halen is that they (along with Devo and Cheap Trick) had originally been under consideration for the starring roles in Allan Arkush’s 1979 movie musical, Rock’N’Roll High School (which ended up starring the Ramones).

But on the delinquent outing that is Hot For Teacher, they seem to make up for that missed opportunity. This is a tune on which the band truly swings – with Roth ‘exuberating’ to the max – over some bumpy territory that has previously been visited on tunes such as ZZ Top’s La Grange, which itself had retraced a path that John Lee Hooker had cut some time earlier.

Here, though, the tempo is ramped up to such a degree that it produces, as Eddie said, “a boogie beyond anything” he’d ever heard. It is excessive. But, in truth, any showing off found here merely complement’s Roth’s genius, dumb-ass, lyrical imagery, which trades brilliantly on the experience of childhood as a time of unfair and daily incarceration (‘Whaddya think the teacher’s gonna look like this year?’; ‘I hope you missed us – we’re back!’; ‘I brought my PENCIL!’).

It was something that the band played up to in the amusing video for the song, in which the band alternate between classroom scenes and segments where they take on the appearance of a Temptations-style vocal group, with matching suits and (badly co-ordinated) dance routines.

At one point Dave can be seen in front of a cage containing the incarcerated Van Halen brothers and Mike Anthony. In his arms he cradles an oversized hourglass – clock-time being the curse of childhood – as he deadpans, “Awww, man, I think the clock is slow”. In the cage behind him, a bad teacher looking like Jungle Jane beats back the guys with a whip.

We can forgive Dave for projecting such juvenile fantasies, not only because they are a celebration of something that is eternally the stuff of rock’n’roll, but because as he once said, he was – temperamentally, at least – approximately 13 years old throughout his career fronting Van Halen: “When you’re 13 you have no responsibility, you don’t think about fixing a certain note, you don’t fear what the critics say, you don’t have a whole coterie of people warning you off it. What makes the tone in my voice is that spirit.”

With the band often working late into the night at 5150, a few songs naturally emerged from grooves that Eddie and Alex were just unable to let go of. With the studio doors open, the sound of Eddie and Alex would waft over nearby homes in the Hollywood hills. Eventually, it became too much for Eddie’s neighbour, Lindsay Wagner – star of 70s TV series The Bionic Woman – who would call Eddie’s wife to ask for the studio doors to be shut.

Within a couple of years, Eddie would have to buy Wagner out of her property to get round the complaints. On one night the tune they were jamming would begin to take shape as Drop Dead Legs, one of Eddie Van Halen’s greatest guitar grooves. As Roth yelps, ‘Dig that steam/ Giant butt’, he takes his cue from the sight of Marilyn Monroe in Billy Wilder’s 1959 movie, Some Like It Hot, as she shimmies past an over-heating train, which is blowing off steam.

“I wish I could have been the violin case Marilyn Monroe was carrying in Some Like It Hot,” he told Spin magazine later, apropos of the movies he’d wished he was in. “In the scene where she’s walking along the side of the train, with all the smoke and the steam coming out, and the way she looked.”

Like Marilyn in motion, this is a tune that sways and shakes and generates heat, and Van Halen, on guitar, is the one on the beat and driving it all. First there’s one guitar, thick and fat – “brown”, as the guitarist might describe it, meaning warm, sweet, anything but sharp and metallic. And it moves the whole thing along on its back, like a drunken man taking up the entire spread of the sidewalk as he staggers forth with a friend on piggyback.

After a few verses and a chorus section, there comes a lull. Then Eddie seems to sound a bugle call (at 1:26 to 1:33), as if calling out to Alex to get up with the beat. Roth, all the time fixating on that image of Marilyn, sings: ‘I get a nut-nut-nuthin but the SHAAAYKS over you.’

The three or possibly four guitars here sound and complement each other more like the pieces in a sax ensemble than the sawing and riffing guitars of a rock’n’roll band. That may sound an odd thing to say, but before he ever picked up a guitar Eddie wanted to play sax (just like his father), and even as late as 1985 was still saying he intended to take it up. The guitarist first blows low, like a baritone sax, then higher in the register of soprano or clarinet, imaginary valves opening and closing as his fingers get the feel for the tone. Below it all is a cool vamp that seems to temper the heat of Eddie’s lead.

This “brown” sound also characterises Panama, a song that, in its automotive lyrical imagery, seems to be very much of its place, Los Angeles – the city of the freeway. In fact, driving metaphorically went straight to the heart of the Diamond Dave philosophy of living in the moment.

“I seem to have my best moments when I don’t consider the creative process,” he told Peter Goddard. “As Bruce [Springsteen] says, just sort of roll down the window and let the wind blow back your hair. You just put the top down and the hair will style itself, you know?”

In Panama we can imagine Roth as the driver of a modest saloon – like the Opel Kadett he would drive from Pasadena to Hollywood in the early days of the band. But he’s a man in disguise, keeps his mojo in the glove compartment, so to speak, and when the moment is right, he can magically transform this clunker into the coolest car on the road – wiping out other pretenders – by intoning the abracadabra word: ‘Panama’.

But, the sexual metaphors are playful, as our hero – on spying a lone female driving past – intones the magic word, ‘Panama’, which enacts the transformation of his clunky car into the machine that will direct the object of his desire onto an on-ramp that leads into his bedroom, and out of reach of the losers who were too slow to get the girl. And it is in the bedroom, with ‘pistons poppin’, that the song (and the action, one assumes) reaches a climax.

Los Angeles also provides Roth’s canvas for Top Jimmy, but this time the picture he painted was more grounded in his day-to-day life. Easily the oddest cut on the album, it features Eddie sounding as if he is playing a guitar strung with elastic bands – partly the result of the fact that he is often slapping the strings. It is one of several tunes on the album – House Of Pain and Girl Gone Bad being the others – that on closer listening develop a kind of swaying, disorientated, quality.

The “Top Jimmy” of the song was one James Koneck, leader of Top Jimmy And The Rhythm Pigs, whose nickname derived from his day job working a Top Taco stand outside of the A&M Records lot in Hollywood. He and Roth became friendly sometime around late 1980, when Dave became the “anonymous financial benefactor” of an after-hours club known as the Zero-Zero, which was then masquerading as an art gallery because it didn’t have a liquor licence.

“I met David when I was bartending at the old Zero-Zero club,” Koneck recounted in a 1984 interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Back when it was on Cahuenga – maybe three years ago. We got real drunk and sang a bunch of old blues together.” The Rhythm Pigs would play “sixty-some Monday nights at the Cathay de Grande,” the sweaty basement of a Vietnamese restaurant in North Hollywood where the events of Top Jimmy took place. “Tom Waits came in and sang Heart Attack And Vine one night. Dave used to get up and sing blues. Ray Manzarek, Albert Collins, Bonnie Bramlett, Percy Mayfield, the Blasters, X and – before she was in Lone Justice – Maria McKee, all came down and jammed with us.”

The Zero-Zero’s regulars included most of the members of LA’s exploding punk and alternative scene, as well as notorious party animals like the soon-to-be-dead John Belushi. Club founder John Pochna recalled that “David showed up at the Zero one night very early on and just loved it. He showed up the first time in a limo, and he had these two chicks with him and Eddie Anderson, his personal security guy. The chicks thought they were going to some fancy place… one of those classy, high-end rock places that Rod Stewart would hang out at.

"They completely freaked out when they saw the look of the place and this raw, totally fucked-up downscale crowd. The chicks were so bummed that David just sent them back out into the limo and then he’d continue to hang out and pick up other chicks… and then he’d send those chicks back and so it would go on and on until the limo was eventually stuffed to the roof with them.”

Brendan Mullen, the recently deceased owner of LA’s first punk club, The Masque – and also a partner in the Zero-Zero – remembers it as “the place on a cool summer’s eve to have sex on the hoods of cars with a joint and a fifth of Jack Daniel’s in one hand and a line of dope on the back of the other.”

It was in the Zero that Roth would hold court in the back room, as beer and pills were swapped in the ramshackle bar area, where Top Jimmy was often to be found dispensing drinks. As it happens, Top Jimmy’s title and lyrics were added very late in the making of the album, around September 1983. Until then this was just an instrumental titled Ripley, after Steve Ripley – the designer of the unique stereo guitar that Van Halen played on the tune.

Ripley himself had played with Leon Russell and Bob Dylan (and now leads the multi-platinum country act, The Tractors). In 1994, he recalled how he and Eddie Van Halen “just became best of friends He was a big supporter of my little company. I don’t how many guitars Edward bought – probably just masses of them.” Once Roth got hold of the tune, though, it would end up being the tale of a night in 1981 at the Cathay De Grande, when Top Jimmy – as if in some great cosmic realignment – finally found himself amongst the stars: ‘Jimmy on the television/Famous people on there with him/Jimmy on the news at five …’

The opening 20 to 30 seconds of Girl Gone Bad features one of Eddie’s most memorable musical phrases, when he taps out a series of breezy, Miles Davis-ish syncopated notes on the neck of his guitar.

“Sometimes the shit just hits you in the middle of the night,” he told Jas Obrecht of Guitar Player magazine. “We were in South America on tour, and I didn’t want to wake up my wife, so I hopped into a closet and hummed the guitar lick into a little tape recorder. You’ve got to force yourself to get out of bed and go, ‘Hey, this might be something some day’.”

The way the tune begins – with that kind of cool, horn-like sound – probably has a lot to do with Eddie scat-singing those notes into a tape machine, dum-dum-dum-de-da-dum, de-da-da-dum-dumdum. This figure, which recurs later in the song slightly altered, has a sense of the anticipated beat common in jazz.

Girl Gone Bad presents a slightly different Eddie than the world was accustomed to. Huge, uncharacteristic chords swell, suggesting nothing so much as heat – with each string bristling as he strokes downwards, almost in slow motion. To listen on is to hear a piece that carries us through space with so much going on that the only comparison is possibly with those bebop combos of 20 and 30 years before: Eddie, starting like Miles Davis is then transformed by the throbbing undertow of Mike’s bass and the way Alex’s kick drum really pushes the band along into some buttery John Coltrane flourishes from the guitar, and then back again to the restrained and cool horn sound of the song’s opening bars. It may be the greatest four-and-a-half-minutes of guitar artistry he released.

The album ends, though, with the heavy sway of House Of Pain, and with Alex beating the life out of some big cymbals. This, in itself, almost induces the bends as it threatens to become submerged in a muddy cacophony. A song with this very title and with a partially similar riff was recorded by the band back in 1976 when they cut demos with Gene Simmons of Kiss. But, really, what we have here is a very different song. On that demo, Eddie and Alex’s parts – aside from the main riff of the verse – were rather more one-dimensional than this House Of Pain.

The revamped song also benefits greatly from a new opening – Alex comes in deceptively off-beat, under Eddie’s bendy, heavy chord opening, as if landing on the ground mid-earthquake, before the song lands on the old 1976 riff. But these thick, fat, guitar parts are not to be found on the earlier tune. As with Drop Dead Legs, Eddie achieves an almost sax-like feel and swing as we hear a band that is much more accomplished than it was in 1976. Roth’s lyric, too, is entirely different, much better, and sung to a new tune. And so ends the record, with a nod to the band’s early days.

Is that all there is? One thing that listeners new to the album today might note is how short the album – at just over 30 minutes – actually is. In 1983, the CD, with its 70-minute-plus capacity had just been launched. So, it was still common to think in terms of the vinyl album and its inherent limitations.

Speaking to Steve Rosen in 1983, Eddie said that they had “all the tracks finished for 13 tunes but we can’t use them all. The songs are four to five minutes long and we don’t like putting more than 35 or 40 minutes on a record because you lose that crispness. It starts sounding like a greatest hit package from the ’50s. You lose fidelity.”

Although rumours have circulated of a version of Wilson Pickett’s In The Midnight Hour, a rendering of an old sea shanty titled Blow The Man Down (true to the spirit of Roth-era Van Halen), and other titles that were trailed by band members in the press – Eat Your Neighbour, Anytime Anyplace – it remains a mystery whether or not anything lies in the vaults.

One thing that is true, however, is that Van Halen are perhaps unique amongst acts of their stature in never having expanded editions of albums, box sets and the like. Even in the old days, there was not a single 7” B-side that wasn’t already on the albums. In other words, they have always tried to keep strict control of what got out. Indeed, given Van Halen’s swift recording methods – which were the norm prior to 1984 – it is perhaps likely that there are no significant leftovers: they went into the studio, cut their tracks in a matter of days, and left.

There is perhaps something to be admired in this desire not to simply give the fans what they keep asking for – but it is a stance that perhaps also diminishes the work they have left behind which, at times, just seems to have been abandoned.

“You can wonder what Roth and Eddie Van Halen are doing in the same band,” Charles Young of Musician wrote in 1984. “It’s hard to imagine two guys with less in common psychologically, yet together they seem to make a complete personality. Extrovert balanced by introvert, logic by intuition, entertainment balanced by artistry.”

The sense of time and distance that had elapsed in the Van Halen camp by late 1984 was evident in other small details, too – some of them obscure and little known. There was, for instance, the promo video for Miloš Forman’s 1984 film Amadeus, which consisted of a compilation of pop music video clips, all set to the music of Mozart and inter-cut with scenes of actor Tom Hulce as the composer – all in an attempt to try and take the film to the new MTV audience.

Significantly, Roth appears in the only specially-filmed segments, at the beginning and the end, as an absurd orchestra conductor dressed in a ludicrous – but supremely Rothian – cheetah-patterned suit and bow tie. Tumbling onstage like one of the Three Stooges, Dave brushes himself down and gathers his composure before rapping the conductor’s baton against a music stand to say, “Alright gentlemen, I have to get this suit back by five, so let’s get it right.” By the end of the year that named this, their biggest album, it was exactly what he was no longer able to do with Van Halen.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 156, in April 2011. The following year, Roth would record with Van Halen again.

John Scanlan is the author of several books, including Easy Riders, Rolling Stones (2015), a study of the idea of the road in 20th century popular music, Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rock’n’roll (2012), Sex Pistols: Poison in the Machine (2016) and Rock ’n ‘ Roll Plays Itself: A Screen History. He is the series editor of Reaktion Books’ ‘Reverb’ series, which publishes studies of the relationship between music and places.