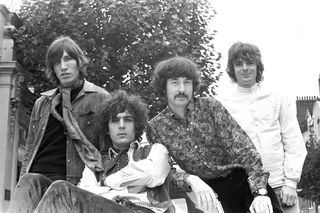

Though they gave life to one of Pink Floyd's best-loved albums, the sessions which eventually birthed the band's ninth studio album, Wish You Were Here, have since become known as one of the most haunting episodes of Pink Floyd’s career.

“I remember going in, and Roger was already in the studio working,” said Richard Wright. “I came in and sat next to Roger. After 10 minutes he said to me: ‘Do you know who that guy is?’ I said: ‘I have no idea. I assumed it was a friend of yours.’ And suddenly I realised it was Syd.”

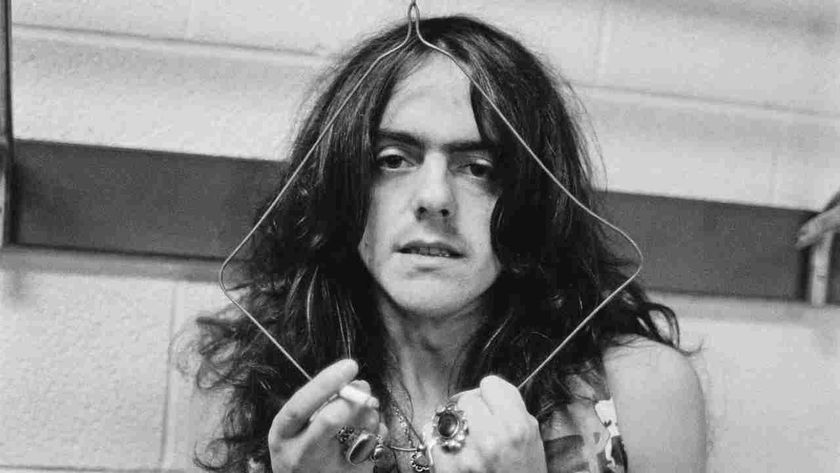

Syd was of course Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd’s former frontman whose pin-up good looks and quirky songwriting had seen Floyd through their first couple of years of success. Nothing could have prepared the band for what happened on that day at Abbey Road studios on June 5, 1975. Barrett had turned up at the London studio anonymously. Although he was only 29 years old he had the appearance of a dishevelled, middle-aged man, obese and with a shaved head and eyebrows. He had turned, as Waters later commented, into “a great, fat, bald, mad person”.

Perhaps even more disturbing was the fact that he turned up precisely on the day the band began the final mixes of their extended tribute to him, Shine On You Crazy Diamond. Syd’s appearance – in both usages of the word – that day was unsettling, to say the least.

This story has now passed into Floyd folklore. Barrett remains a curious spectre that has hung over the band ever since his forced departure in 1968. As with all Pink Floyd albums, you find yourself looking backwards rather than forwards, and Roger Waters’s feelings of guilt, frustration and sadness towards his old school friend came to the fore on Wish You Were Here as he explored themes of loneliness, isolation and absence.

Much of this was born out of the massive high the band had experienced post-Dark Side Of The Moon. The huge success of that album had propelled Floyd from being a relatively anonymous cult rock act to mainstream public property. They were now as popular – perhaps even more so – than Led Zeppelin, The Who and the Rolling Stones. But then, from a personal perspective, things came crashing down just as fast as they had built up.

As with any industry that relies on sales, their record label wanted a lot more of the same – and fast. But repeating that level of success was not going to be easy for anyone, let alone Pink Floyd, who first had to come to terms with the fact that they had, at last, ‘made it’.

The non-stop tour they had been on suddenly stopped, rather abruptly, in June 1973, after another lengthy trek around North America. Thereafter Pink Floyd played just four more shows that year.

The remainder of 1973 saw a dramatic change for the band. Until then they had lived in each other’s pockets, but now they wanted some space. Both Gilmour and Mason sought refuge in projects outside of the band: Gilmour helped the band Unicorn launch their career. He also discovered a talented teenage singer-songwriter by the name of Kate Bush. He became her mentor, eventually influencing EMI’s decision to sign her. Mason, meanwhile, lent his hand to producing records by Principal Edwards Magic Theatre, and also Robert Wyatt, with whom he later performed at London’s Theatre Royal, and appeared on Top Of The Pops in September 1974 performing Wyatt’s cover of The Monkees’ I’m A Believer.

So when Pink Floyd did finally reconvene at Abbey Road, on October 1, 1973, they were quite at ease with their detached lives. They were in a state of inertia, and were bereft of any ideas about what to do next. They felt an obligation to produce ‘something’, even if it meant doing it just for the sake of it. And that is more or less what they ended up doing.

In what has now become known as Household Objects, the band avoided the real issue and instead diverted their energies into a prolonged and agonising project of trying to create an entire album using only sounds produced by household objects. Demonstrating their method to a Sounds journalist, Gilmour recalled: “We actually built a thing with a stretched rubber band this long [about two feet]. There was a G-clamp this end fixing it to a table, and at this end there was a cigarette lighter for a bridge. And then there was a set of matchsticks taped down this end. You stretch it and you can get a really good bass sound. Oh, and we used aerosol sprays and pulling rolls of Sellotape out to different lengths – the further away it gets, the note changes.” He adds with some sense of achievement and pride that: “We got three or four tracks down.”

Ultimately it was a wasted effort, although Gilmour did reveal in recent years that the technique of running a finger around the rim of a glass to produce a note was eventually put to some use: “We did actually use some of the Household Objects. The wine glasses were in some of the music at the beginning of Shine On You Crazy Diamond.”

Recording sheets reveal a curious collection of takes that include Carrot Crunching and Papa Was A Rolling Floyd. Only two tracks appear to have been worked on for any given length of time: Nozee, and the appropriately titled The Hard Way.

Despite putting on a brave face, even Floyd had to concede defeat, and after reviewing the material in November 19, further sessions for the project were cancelled.

Around Christmas 1973 the band booked time at a rehearsal studio in London’s King’s Cross. In complete contrast to their efforts at Abbey Road, where there was pressure to come up with the goods, their creative juices began to flow in a more natural way, and many of the songs they would write for their next two albums emerged – not least a stunning new song tentatively referred to as Shine On.

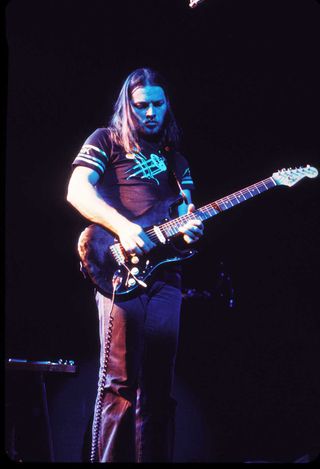

“We started playing together and writing in the way we’d written a lot of things before, in the same way that Echoes was written,” Waters remembered. “Shine On You Crazy Diamond was written in exactly the same way, with odd little musical ideas coming out of various people. The first one, the main phrase, came from Dave; the first loud guitar phrase you can hear on the album [Wish You Were Here] was the starting point, and we worked from there until we had the various parts.”

A second number, titled Raving And Drooling (eventually turning into Sheep on Animals) was also worked out. Both songs were premiered in June during a short tour of France.

Significantly, the band also paid some serious attention to their stage presentation for the very first time that year. They may have still been performing Echoes and The Dark Side Of The Moon in their entirety, but now the show featured a 40-foot circular screen that was used to project specially prepared films onto. In one particularly memorable section, a sequence of flying animated clocks, created by Ian Emes, was used for the opening of Time. The screen also served as a backdrop at the close of Shine On, when a huge, rotating mirror-ball was raised in front of it and hit with a spotlight to produce blinding shards of white light, under cover of which the band exited the stage. Fireworks and rockets also provided some spectacular visual effects.

In what was billed as the 1974 British Winter Tour, from November to early December, another new song, Gotta Be Crazy (which later became Dogs on the Animals album) joined Shine On You Crazy Diamond and Raving And Drooling. Waters had written it at home, and Gilmour added the chords at a later date. All three songs were very harsh in comparison to the softer melodies of The Dark Side Of The Moon, and the lyrics were an unforgiving tirade against society’s current values.

Whether social commentary was what people wanted to hear from Pink Floyd at that time is debatable, but it provoked the first time that a national music paper had taken the band to task. This was an unusual event in itself – throughout the early 70s Pink Floyd had reigned supreme – but the concerts at Wembley Empire Pool (now Wembley Arena) in mid-November brought disdain from a younger generation of critics, principally Nick Kent of the NME, who described Floyd’s show as “a pallid excuse for creative music”.

Maybe Pink Floyd were becoming detached from the real world. They were certainly becoming increasingly detached from each other. Roger Waters has, on many occasions, stated that The Dark Side Of The Moon had more or less finished the group as a creative force, since with it they had fulfilled at a stroke the shared ambition of fame and fortune.

Nevertheless, on January 13, 1975 Pink Floyd convened at EMI’s newly refitted Studio 3 at Abbey Road to start work on their seventh studio album. Because of their touring commitments, the sessions took place either side of and between two tours of North America. As a result, the recording process became very protracted and fragmented, pushing the release back to September. Once again Pink Floyd were afforded the luxury of being able to refine those new songs on stage.

- The Top 10 Best Pink Floyd Roger Waters Songs

- Syd Barrett: A Saucerful Of Secrets

- Roger Waters: The Buyer's Guide

The first of those tours was announced in March and, in a new departure, carried no national advertising. Instead, CBS Records, who had recently struck a deal with the band over their previous label Capitol Records, used FM radio to alert fans to a specially prepared Pink Floyd show which was simul-cast early that month to the seven major cities where the band were booked to play.

Within hours, all of the dates had completely sold out, breaking each venue’s box office records, including those of the Los Angeles Sports Arena, which sold all of its 67,000 tickets for the band’s scheduled four-night run in a single day. A fifth LA show sold out within hours, and the demand for tickets was so great that Floyd’s residency could easily have been extended further.

American fans’ response to the tour was simply overwhelming. It bewildered many city newspapers that a band whom many had never even heard of could have such a huge following and do better business than the Rolling Stones, who were also on tour, yet comprise such anonymous personalities.

On stage, The Dark Side Of The Moon still formed the mainstay of the second half of the show, with Echoes as an encore, but the first half, although still opening with Raving And Drooling and Gotta Be Crazy, now divided the lengthy Shine On You Crazy Diamond into two halves which straddled another new composition, Have A Cigar.

Although the tour was an outstanding success, it was best remembered for the heavy-handed actions of the Los Angeles Police Department, which arrested over 500 fans during the five-night run at the Sports Arena in late April. Police Chief Ed Davis, in a speech to businessmen a week before the concerts, described the upcoming shows as an “illegal pot festival” and gave the assurance that he was committed to bringing the full weight of the law to bear on even the most minor of offences committed at or in the grounds of the venue.

Rolling Stone’s June 1975 edition ran an extensive report that gave evidence that many other venues in the greater Los Angeles area had been subjected to the heavy-handed actions of Chief Davis, who was quoted as saying: “I’m the meanest chief of police in the history of the United States.”

Officially only 75 officers were deployed at the shows on each of the five nights Pink Floyd played, but venue management estimated the figure to be nearer 200. Of the 511 arrests, the majority were for possession of marijuana. The police justified their actions by claiming that there were a few more serious offences, including cocaine dealing and possession of a loaded gun. This fact made more headline news in the LA Times than the concerts themselves. The riotous scenes were later depicted in the opening sequence of the movie The Wall – the band did actually have to ram a police barrier to get into their own concert.

Back at Abbey Road in May, Waters was keen to carry on working, despite obvious tensions. “We pressed on regardless of the general ennui for a few weeks and then things came to a bit of a head,” he recalls. “I felt that the only way I could retain interest in the project was to try to make the album relate to what was going on there and then – the fact that no one was really looking each other in the eye, and that it was all very mechanical.” Waters’s vision was cemented at a band meeting. “We all sat round and unburdened ourselves a lot, and I took notes on what everybody was saying. It was a meeting about what wasn’t happening and why.”

Waters extended further still his ideas of general themes of absence and detachment by opting to write yet more new material.

“I suggested that we change it,” Waters continues. “That we didn’t do the other two songs [Raving And Drooling and Gotta Be Crazy], but tried somehow to make a bridge between the first and second halves of Shine On, which is how Welcome To The Machine, Wish You Were Here and Have A Cigar came in… Dave was always clear that he wanted to do the other two songs – he never quite copped what I was talking about. But Rick did and Nicky did, and he was outvoted so we went on.”

With Gilmour and Waters – the principal players in the band – at complete cross purposes, recording carried on, even if Gilmour wasn’t convinced: “After Dark Side we really were floundering around. I wanted to make the next album more musical. I always thought that Roger’s emergence as a great lyric writer on the last album was such that he came to overshadow the music.”

Even by agreeing to disagree there was also a sense they were being held back by general lethargy, promoted by an alarming divorce rate within the band. Although his own marriage had hit the skids very recently, Waters was able to divert his energies into songwriting. But in Mason’s case his impending split “manifested itself into complete, well, rigor mortis. I didn’t quite have to be carried about, but I wasn’t interested. I couldn’t get myself to sort out the drumming, and that of course drove everyone else even crazier.”

Having finally settled on what it was they were now going to record, they set about putting it all down on tape. Shine On was to be split into two halves: Parts 1-5 and 6-9. Part 5 eventually featured their tour saxophonist Dick Parry, who switches between baritone and tenor sax. Particularly problematic were Waters’s vocal sessions. “It was right on the edge of my range,” Waters recalled. “I always felt very insecure about singing anyway because I’m not naturally able to sing well. I know what I want to do but I don’t have the ability to do it well. It was fantastically boring to record, cos I had to do it line by line, doing it over and over again just to get it sounding reasonable.”

Consequently further tensions surfaced as the boredom of the process took its toll and band members became increasingly disinterested in turning up for sessions at all. “Punctuality became an issue,” Mason recalled. “If two of us were on time and the others were late, we were quite capable of working ourselves up into a righteous fury. The following day the roles could easily be reversed. None of us was free from blame.”

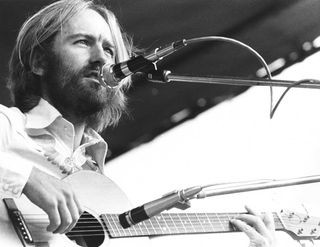

Little changed when they came to record Have A Cigar, and again Waters’s singing was showing its limitations. This time though, their friend Roy Harper was drafted in to sing. “Roy was recording in the studio anyway,” recalled Waters, “and was in and out all the time. I can’t remember who suggested it, maybe I did, probably hoping everybody would go: ‘Oh no, Rog, you do it’. But they didn’t. They all went: ‘Oh yeah, that’s a good idea.’ He did it, and everybody went: ‘Oh, terrific!’ So that was that.”

It was an instantly regrettable decision, and although Waters reluctantly conceded a credit on the album, there was certainly no question of payment. Tape engineer John Leckie recalled Waters saying to Harper that they must make sure he get paid for his efforts. “And Roy said: ‘Just get me a life season ticket to Lord’s.’ He kept prompting Roger, but it never came. About 10 years later, Roy wrote a letter to Roger and decided that, due to the success of Wish You Were Here, £10,000 would be adequate. And heard nothing at all.”

Have A Cigar is Waters’s cynical take on the music industry, and contains the immortal line: ‘Oh by the way, which one’s Pink?’ “We did have people who would say to us: “Which one’s Pink”’ and stuff like that,” Gilmour recalled. “There were an awful lot of people who thought Pink Floyd was the name of the lead singer, and that was Pink himself and the band. That’s how it all came about. It was quite genuine.” In many respects Waters was biting the very hand that was feeding him.

On the eve of their departure from England to begin their second tour of North America, Syd Barrett made his aforementioned appearance at Abbey Road. It was the last time the band ever saw him. Part 9 of Shine On You Crazy Diamond includes the melody from See Emily Play as the track fades out. An afterthought? Perhaps.

“I’m very sad about Syd,” Waters later declared. “I wasn’t for years. For years, I suppose he was a threat because of all that bollocks written about him and us. Of course he was very important, and the band would never have fucking started without him, but on the other hand it couldn’t have gone on with him. He may or may not be important in rock’n’roll anthology terms, but he’s certainly not nearly as important in terms of Pink Floyd. Shine On is not really about Syd, he’s just a symbol for the extremes of absence some people have to indulge in because it’s the only way they can cope with how fucking sad it is – modern life – is to withdraw completely.”

Back in the States and back on the road, an ambitious attempt was made to boost the visual impact of the shows, which were now taking place in enormous outdoor stadiums. Floyd turned to Mark Fisher and Jonathan Park, two accomplished, London-based architectural designers with experience of advanced inflatable and pneumatic structures. Their brief was to construct a huge pyramid that would sail above the stage and radiate light beams in a way that was reminiscent of the cover of The Dark Side Of The Moon.

Assembled in record time, the structure made its maiden flight at the Atlanta Stadium on June 7. But, having failed to function properly, it didn’t fly again until the show at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh on June 20. The huge pyramid, its base 60-feet square, was held in place by guides as the top section separated at the climax of the show and rose above the stadium. As it separated, fans were heard to yell: “It’s giving birth!” just before a gust of wind blew it over, dislodging the helium balloon inside which was never to be seen again. Also not seen again was the top of the pyramid which, after rising out and over the stadium, crashed into a number of vehicles in the car park, and was shredded in minutes by souvenir-hungry fans.

In a dramatic finalé to the tour, Pink Floyd’s crew decided to go out with a bang and used up all of the remaining pyrotechnic charges around the stadium scoreboard. The resultant explosion at the climax of the show blew it to pieces, the blast even shattering the windows of nearby buildings.

On July 5, with the US tour just a few days behind them, Pink Floyd played a long-awaited homecoming open-air concert at Knebworth Park in rural Hertfordshire. The concert was dogged by problems from the start, among them a road crew still jet-lagged from the US tour they had only just got back from. Another was the band’s stage entrance, which had been planned precisely to coincide with the fly-past of two World War II Spitfires. In the event, the fighters buzzed the audience at low level while the roadies were still frantically trying to prepare the stage. The band came on unprepared, and their set was tired, uninspired and marred throughout by technical breakdowns, mainly due to fluctuations in maintaining generator power.

Predictably, the band again fell foul of the UK music press. Some reviewers accused them of turning in a poor performance, some criticised them for playing The Dark Side Of The Moon yet again, others took them to task for playing in their own country all too infrequently. Whereas Pink Floyd had once been seen as stalwarts of the British rock underground, regular performers at festivals and small UK venues, the view now was that the industry machine had taken over and the band had overreached themselves.

What the critical journalists failed to realise was that Floyd’s overwhelming support over the years had actually contributed to the massive expansion. Their fan-base had swelled considerably, which meant Floyd could no longer play small-scale concerts ever again. As much as the band disliked it, they and their management knew that an American tour was far more lucrative than a trek around the UK could ever be. Underlining this difference, their American tour had generated enough album sales to propel The Dark Side Of The Moon back into the Billboard Top 100 album chart on April 12 ,1975. It remained there until March 6, 1977.

Money issues aside, the North American tour had left the band cold. There was a distinct feeling of isolation, with the back row of shows getting further and further away. The fans’ intense enthusiasm and tendency to make lots of noise meant that a Pink Floyd concert in the States was akin to an FA Cup Final back home. Their shows had ceased to become an intimate performance for the fans and more like a large scale party for the masses, regardless of the entertainment.

Such was this sense of alienation, at least in Roger Waters’s mind, that it led him to believe there might as well have been a brick wall between band and audience. “I cast myself back into how fucking dreadful I felt on the last American tour, with all those thousands and thousands and thousands of drunken kids smashing each other to pieces. I felt dreadful because it had nothing to do with us – I didn’t think there was any contact between us and them.” It was an idea that Waters would nurture over the next few years and lead to him producing something truly spectacular.

In the meantime, work progressed on the new album’s remaining two tracks, starting with Welcome To The Machine. Once again Waters delivered a cynical take on the treadmill of existence. It was sung by Gilmour, whose warmer vocal delivery actually disorientates the listener. Gilmour recalled the development of the track being “very much a made-up-in-the-studio thing, which was all built up from a basic throbbing made on a VCS3 [synthesiser], with a one-repeat echo used so that each boom is followed by an echo repeat to give the throb. With a number like that, you don’t start off with a regular concept of group structure or anything, and there’s no backing track either. Really it is just a studio proposition where we’re using tape for its own ends – a form of collage using sound.”

Ordinarily, the band would develop ideas for songs through music, but in the case of the title track it was Gilmour who built the music around an existing piece of poetry by Waters. Wish You Were Here’s masterstroke is the use of a tinny transistor radio sound that links the end of Shine On… to Gilmour’s delicate guitar work at the beginning of Wish You Were Here – apparently recorded on Gilmour’s car radio, with an excerpt from Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony creeping in. “It’s all meant to sound like the first track getting sucked into the radio, with one person sitting in the room playing guitar along to the radio,” he explained.

Also playing on the album’s title track was French jazz violinist Stéphane Grappelli, who at the time was recording with classical violin star Yehudi Menuhin at Abbey Road. It has long been claimed that the tapes of Grappelli’s recording for Floyd were lost or recorded over, but thankfully that is not the case. And while it’s not obvious on the final mix, he definitely appears at the very end of the track, although his contribution is barely audible. He didn’t get a credit on the sleeve either but he reportedly did receive a small fee.

“It was terrific fun,” mused Gilmour, “avoiding his wandering hands…”

The artwork was for the Wish You Were Here album was again by the Hipgnosis design team of Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell. It works as a very specific visual representation of the subject matter, and extends themes of presence and absence in equal measure.

The front cover photograph, taken at Warner Brothers studios in LA, featured stuntmen Danny Rogers and Ronnie Rondell. It was “the idea of someone getting ripped off, or burned, as he agrees a deal with a handshake,” explained Aubrey Powell. Even the outer edge of the photograph has the look of being singed.

Elsewhere a diver doesn’t disturb the water on entry; a salesman is faceless; and a veil obscures the photo of a naked woman. All of this was then encased in a black shrink-wrap outer covering, which made the whole album look appropriately anonymous.

“The record label went mad!” recalled Powell. When it was released the album had on it a hastily designed (by George Hardy) sticker, illustrating the four elements and a pair of mechanical shaking hands, and bearing the band’s name and the album title.

Ultimately, Wish You Were Here benefits from Waters’s less confrontational lyrics (these would resurface on their next album, Animals), and Gilmour and Wright’s classic atmospherics to produce what is quite possibly the definitive Pink Floyd album. It is detached yet engaging.

Wish You Were Here was released on September 15 and went straight to the top of the album charts on both sides of the Atlantic. It is estimated to have sold more than of 14 million copies worldwide.

As Richard Wright fondly remembered: “I think that’s my favourite album that the Floyd ever did. I feel the best material from the Floyd was definitely when two or three of us co-wrote something together. Afterwards we lost that; there wasn’t that feeling of interplay of ideas between the band.”