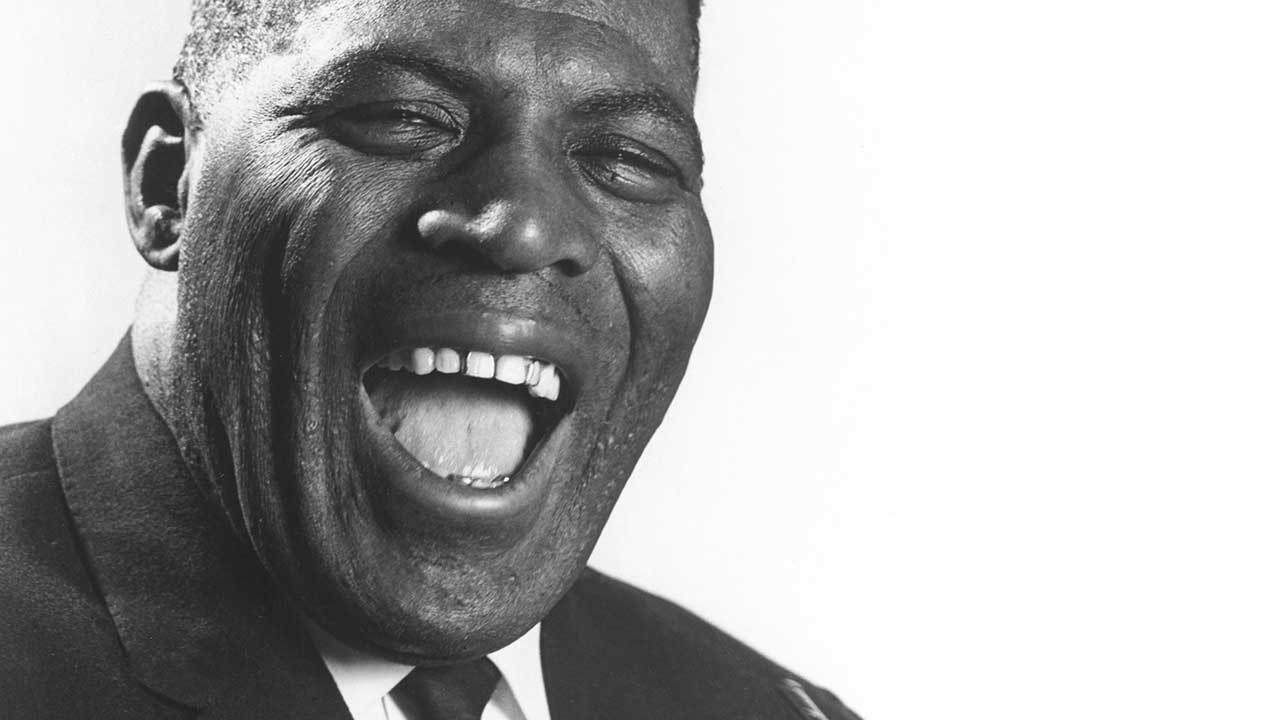

When Ronnie Wood reminded Classic Rock last year that the pioneers of American blues were “dangerous men”, he hardly needed to name the tyrant-in-chief. He might have been born Chester Arthur Burnett in 1910, but the nom de guerre Howlin’ Wolf suited the Chicago bluesman better.

An intimidating physical presence with a short fuse and zero reverence for the white-boy boomers who touched his hem, Wolf’s bite was almost as lethal as his bark. When he sang, in a gale-force boom that blew down the house, there was nothing else in the world that felt so powerful – and almost a half-century after his death, his catalogue remains the real deal.

Memphis Days: The Definitive Edition Vol. 1 & 2 (Bear Family, 1996)

It took one rogue genius to talent-spot another, with Ike Turner credited, in 1951, for lifting Wolf from obscurity and arranging his first sessions at Sam Phillips’ Memphis Recording Service (soon to be Sun). The producer would later recall “the fervour on his face… the veins coming out on his neck… he sang with his damn soul”, and these compilations catch all that.

On standouts like Baby Ride With Me, the bluesman’s voice is a primal rasp that demands attention and respect, while guitarist Willie Johnson gets the memo and rolls his amp into the red. From here, there was no keeping the Wolf from the door.

Moanin’ In The Moonlight (Chess, 1959)

Wolf had been spitting out classic sides throughout the decade before this debut Chess LP put them all in one place. Benchmarks like the stinger-riff Smokestack Lightnin’, the Zep-referenced How Many More Years and Willie Dixon’s much-covered Evil (Is Going On) have been overplayed for decades, but that hasn’t blunted their impact here, Wolf singing with the emotional focus of a power drill.

The title track, too, is a must-hear, with a wide-open harp ‘n’ slide-guitar groove giving the bluesman a canvas to growl, sneer and literally howl at the moon – while scoring him a R&B chart Top 10 hit.

Colloquially known as the Rockin’ Chair album, this second set from Chess gathered Wolf’s turn-of-the-decade singles, and certified the legend. By now, Willie Dixon’s pen was scratching at pace (a key reason for Wolf’s bitter rivalry with Muddy Waters was each bluesman’s suspicion that the other was being gifted the superior songs).

There’s no question that Wolf got the prime meat here: the Stones couldn’t touch his Red Rooster, while the swagger and room-filling shout of Spoonful was beyond even Cream. “Let me tell you something,” guitarist Hubert Sumlin recalled of the latter, “it was a number one tune we had there.”

The Real Folk Blues (Chess, 1965)

In the mid-’60s, Chess anthologised many of its stars – from John Lee Hooker to Sonny Boy Williamson II – in the Real Folk Blues compilation series. But don’t be fooled by the umbrella title: there’s nothing remotely shoes-off about the Wolf’s entry, which sets out its stall with the self-penned bob ‘n’ weave rave-up Killing Floor (the band’s instrumentation as lacerating as their boss’s voice), and even feels dangerous when they slow it down on the Cream-covered Sittin’ On The Top of The World.

These days, you’ll find these tunes bundled as a two-fer with 1967’s almost-as-good More Real Folk Blues – so no excuse.

The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions (Chess, 1971)

When Chess producer Norman Dayron floated the ‘master-and-student’ concept to Eric Clapton backstage in San Francisco, the British bluesman jumped at the chance. The Wolf took more convincing: even once sessions began at Olympic with a revolving-door of luminaries including Ringo Starr, Bill Wyman and Mick Jagger, the senior statesman was a powder-keg (“On the second day,” says Dayron, “Wolf got surly. He was a fish out of water”).

It’s not as good as the credits would suggest, but when this makeshift lineup cooks on I Ain’t Superstitious and Poor Boy, it’s far more than a gimmick.

Live & Cookin’ At Alice’s Revisited (Chess, 1972)

“Thank you very much. I really appreciate you, because you are my people. You made me and I’m gonna howl for ya”. By 1972, Wolf might have been in failing health, his arrhythmia controlled by prescription drugs, his kidneys soon to go rogue – but he was as good as his word on this late-period live set.

A cover of arch-rival Muddy Waters’ Mean Mistreater is maybe the best collision of the band and its leader, but it’s The Big House that’s the real treasure, the bluesman exhorting his players to “make it funky” as he owns the eye of the storm. Four years later, he was dead.

The price tag on Amazon is a joke – over £500 at time of writing – but it's worth a trip to Discogs, because for those who want to immerse themselves in Wolf World, this three-disc box-set manages the near-impossible and does justice to the legend.

Chess’s chronological selection of 75 tracks is hard to fault – taking in big-hitters, rarities and acoustic curveballs – the sound as sharp as you could realistically hope for, and the spoken-word tracks a rare window into a man who gave little away in his lifetime. Throw in a well-assembled booklet including rare archive shots, and it’s a shoo-in for completists.

The Howlin’ Wolf Story DVD (Bluebird, 2009)

You had to see Wolf live to feel his full force of nature: a pleasure denied to us since his swansong at the Chicago Amphitheater in November 1975. Still, this DVD does a fine job of reanimating the bluesman, combing the archives for gold like the 1965 Shindig! variety show appearance (complete with awed introduction by Mick Jagger and Brian Jones) and the festival set where Wolf butts heads with a heckling Son House (“You had a chance wi’ your life, but you ain’t done nuthin’ with it!”).

With testimony from family and bandmates like Sumlin, too, it’s as close you’ll come to knowing what made him tick.

Smokestack Lightning: The Complete Chess Masters 1951-1960 (Chess, 2011)

A second impossibly lavish multi-disc boxset might feel like overkill, but Smokestack Lightning justifies its release, covering different ground from The Chess Box and drilling deep into the white heat of Wolf’s first decade at the Chicago label. As we’ve established, the Wolf of later years has his merits, but gun to the head, this early material is the stuff: primal, powerful and with everything to prove.

Be warned: the number of alternate takes across these 97 tracks means dabblers shouldn’t apply. But for the true obsessives, you’ll find no better.