This article first appeared in The Blues Magazine #2, August 2012.

It’s impossible to guess what the blues might’ve sounded like, had there never been a Howlin’ Wolf – that mountain of a man, with a voice like a thunder-crack, a sulphur-throated force of nature whose music seduced generations of blues fans and blues musicians that followed.

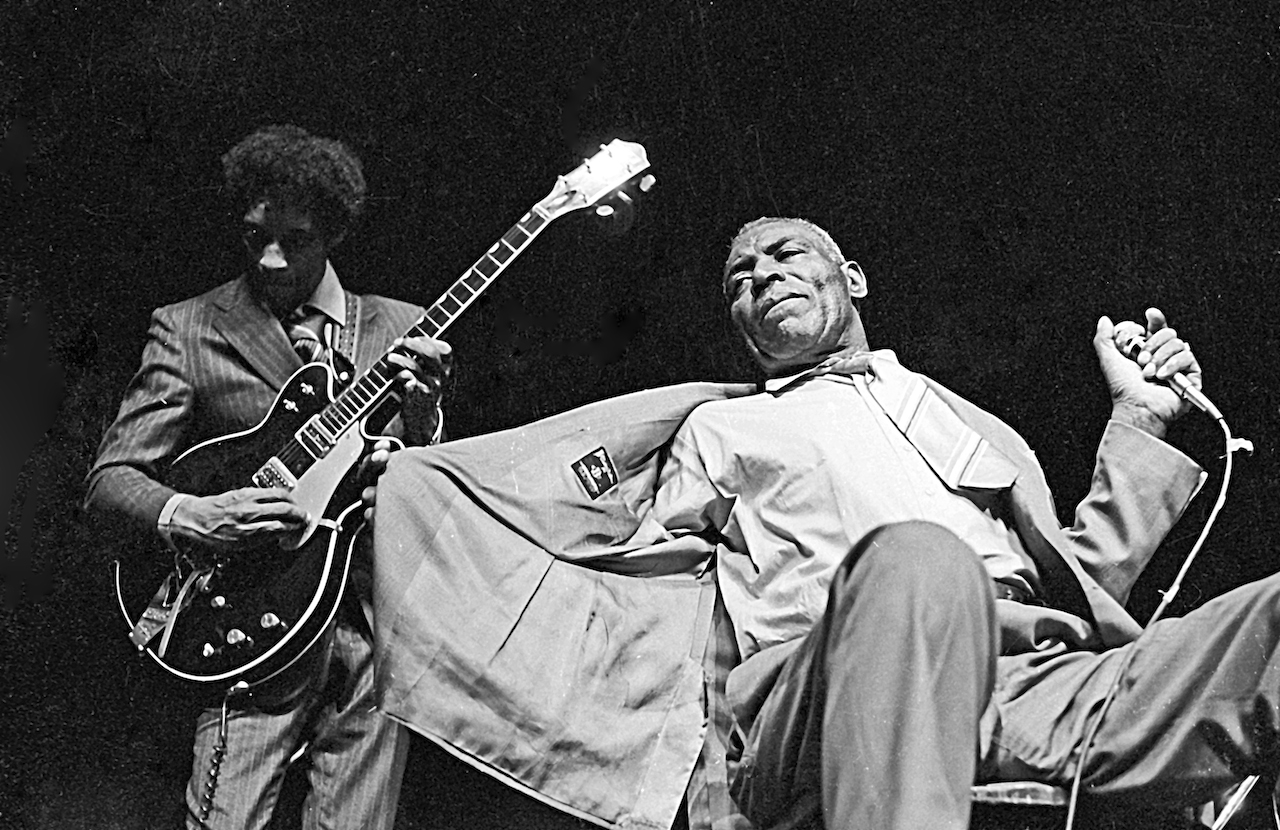

But it’s similarly impossible to gauge what Howlin’ Wolf (and, by logical extension, the blues) might’ve sounded like, had there never been a Hubert Sumlin. Born in Mississippi on November 16, 1931, a 23-year-old Sumlin was head-hunted by Howlin’ Wolf in Memphis, and invited to follow Wolf north to Chicago, to become his loyal sideman. Having learned guitar from Charley Patton, and worked with both Son House and Robert Johnson, Wolf clearly knew a thing or two about blues guitarists; Sumlin was the guitarist he chose, above all others.

Sumlin appeared on the lion’s share of Wolf’s watershed sides: the 1959 compilation Moanin’ In The Moonlight, 1962’s Howlin’ Wolf (aka The Rockin’ Chair Album), 1973’s final curtain The Back Door Wolf – Hubert was on them all, his tone unmistakeable, his style massively influential. After Wolf’s death, early in 1976, Sumlin continued to perform, and to record – indeed, he was recording with The Blues’ own Stephen Dale Petit days before his own death in 2011.

In August 2008, a 76-year-old Sumlin gave this interview from his home in Totowa, New Jersey, to The Blues’ Matthew Frost. We share it with you now, so you might better know this true blues original.

How did you first meet Howlin’ Wolf?

When I first met the Wolf, he scared the devil out of me, but I liked that guy. I hoboed down to this club he was playing on the Mississippi River in Arkansas – I went to see him but, man, I stepped on some Coca-Cola crates up in the back where he was playing. There was one window up, and there was a big fan where they poured all the smoke out, and somebody smashed these crates out from under me – and over on Wolf’s head! Well, I believe he knew that I was coming out there with the fan and everything ‘cos he held his hands out, caught me and then moved. He told them: ‘You bring this young man a chair and don’t bring him nothing to drink and I’m gonna see that he sit here.’ And I stayed until they finished work and he brought me home. He told my mother, ‘Don’t whup him, please, because I may even need him one day.’ Sure ’nuff, you know, I end up with him.

So how did you first start playing with him?

Well, me and James Cotton formed this little band and played all over Mississippi and Arkansas with Wolf, who was already established. We played first, and then Wolf came in and he did his thing and he was gone. Then he also gave us 15 minutes of his 30-minute show that he did on a radio station in West Memphis. That’s when things started to happen. Then he took his 15 minutes back, man, ’cos we got too good. ‘I’m gonna show you, you’re a little bit too much for me. Maybe one day I might hire you guys!’

So when did he hire you?

I was staying with James Cotton in West Memphis, and Wolf came by and said, ‘I’m going to Chicago, man, I’m putting my band down, I got a new band.’ Wolf had been to Chicago already to form that group, and I didn’t know that. Cotton told me, ‘Hubert, you make more money with Wolf than you will with me. I hope you send back and get me!’ That’s what we did. I joined Wolf and he had Jody Williams, Earl Phillips and Hosea Lee Kennard, the piano player, so it was great. We really had a nice time. I was with Wolf almost 24 years… I stayed with the guy until he passed [in 1976].

When you were working on a song with Wolf, what was the process?

We always worked on songs in his garage. I don’t care where he lived, on the West Side, or when he moved in his new house, there was still the garage. We were rehearsing there and got that stuff together before the horn section came in. I knew how it wanted to go, and that was it. So we would start arguing, but we end up right! We end up, you understand, recording. Willie Dixon, the bass player, would come sometime, but we didn’t need him. All we worked on was the foundation of the music – the bass would’ve been nice, but I knew what the bass was gonna do and Wolf did, too. And that was it.

So would Wolf come up with lyrics first?

That’s right. Look, Willie Dixon wrote a lot of the numbers we would play but he didn’t write ‘em all. He didn’t write 300 Pounds Of Joy. He didn’t write Goin’ Down Slow. That was already written by St Louis Jimmy. He happened to be sitting in the middle of me and Wolf in the studio and he gave Wolf Goin’ Down Slow, with Willie Dixon talking on it, you know. He start talking and then Wolf came in second. Yup.

What do you remember about Chess Studios?

We made our first record on South Cottage Grove Avenue on the South Side, which was one room in a little apartment. That was a ‘soul’ place there. I liked it. They even had stove pipes for an echo chamber. And one mic – one mic to get a whole studio! Little Walter and all these guys that blowed harp had their PA system, sitting out always in the studio and blow it over their mic, but the sound come out into the big mic. Then they moved out on Michigan Avenue, and they had the studios upstairs and offices downstairs. They went from there over to almost on Canal Street, which was the building that took up nearly a block and a half. There were sessions going on all the time, ‘cos Chess had so many artists – The Moonglows, Chuck Berry… Everybody started recording for this guy, even The Rolling Stones!

- Whose version of Little Red Rooster is better: Howlin' Wolf's or the Stones'?

- Willie Dixon: I Am The Blues

- Buyer's Guide: Muddy Waters

- Wilko Johnson And The Best Of Chess Records

And how long would it take you to record one track?

Oh, about two hours. But you can go back down if you missed something. I’d say a day, you’d do and you’re outta there.

What guitars did you play with Howlin’ Wolf?

I played a Gibson and I had the Kay when I first got with him. Me and Jody both had those guitars. I won three WC Handy Awards and they gave me a Gibson guitar – they had it made for me. They wanted a duplicate of the guitar that I played with Wolf, ‘cos I wouldn’t let ‘em have my old guitar, man. They made this guitar just like my old one… the P90 pick-ups and everything. I’ve got a lot of guitars, about 60. All kinds!

Tell me your stand-out memories of the Howlin’ Wolf track Spoonful?

Let me tell you something… It was a number one tune we had there. I had a nice time recording all the stuff that we did. I put the music to a lot of his numbers, that’s what I can say.

What do you remember about Smokestack Lightning?

Smokestack Lightning? After I Asked For Water (She Gave Me Gasoline), this is what we made. He’d made this record before, but we recorded it again. Ask For Water is on the same level, on the same beat, the same music, except for one thing, a few notes change. It didn’t take me no time at all to [write the riff]. I love it! And not only me, everybody else. Every time I play, man, I play the number. I have to. I can’t sing as good as he can but I can play it. It’s one of my favourites, man, sure enough.

How did you start playing guitar?

When I was small, my brother… He was my idol, I tell ya. And he had one string upside out the house and he learned to play that one string, and then when he got to four strings, he quit. He put the strings up ‘cos he didn’t have a guitar, but he just know how to play is all. And so I watched him. And that guy hit me one day. I broke one of the strings upside the wall. But what happened, it unwound round the nail, ‘cos how can you break baling wire, which you bale hay with? You cannot break it, man. It’s almost thick as your little finger. Anyway, he hit me with a cement block and boy, I saw stars, man! No kidding. I couldn’t get up. And my brother ran away and stayed gone for three days. But I met my mama coming from Greenwood where she work in this funeral home, making eight dollars a week. And she asked me what’s wrong with me. I told her what happened and she said, ‘That’s alright, son, next week I’m gonna buy you something.’ She say, ‘I know you ain’t dead but when he back home, he gonna get it’, you know. And sure ‘nuff, when he come home, she whupped him. And my daddy whupped him.

And so she bought me an eight-dollar guitar with no name. I played that guitar, boy, in church. I found this old warped record by Charley Patton and I could hear this guy sing and he moan, man… ‘Oooo, Ooooo, Ooooo’ and that was it. I knew right then what the blues was all about. And then I heard the Wolf, I heard Muddy, I heard all these guys play.

In the early 1970s you accompanied Howlin’ Wolf to London, where the pair of you recorded alongside British rock superstars like Eric Clapton, the Stones’ Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts, Steve Winwood and Ringo Starr, cutting tracks that would later be released as the 1974 album, The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions. What are your memories of those sessions?

You know, the Chess Brothers didn’t want me to go. They wanted The Rolling Stones. At that time, they wanted Wolf to be like The Beatles or Chuck Berry. But Wolf told me I was going anyway. Then, while Wolf and Chess was discussing me going and everything, Eric Clapton called. I don’t know what got into him to call, but he did, and said he wanted to speak to Leonard [Chess].

So Leonard got the phone and the speakers were on, so you could hear everything. And so he told him if I wasn’t gonna be there, he wasn’t gonna be there… Because we’d made Goin’ Down Slow. He’d heard the guitar and he wanted to meet me anyway… And that’s what happened. At the London Sessions, we sat down in front of one another and played. I’d already heard [Clapton’s playing]. I knowed it. I liked it at the beginning. I heard the things he did with Cream, all these people, you know. I know he was alright.

What happened when Howlin’ Wolf died?

Well, we were supposed to come to Europe that week, and he told me to go ahead. He said, ‘Make everything alright, keep everything going for us,’ ‘cos he got his reputation and the people, they like his records, and they liked him, and they liked us. And so I went on to Paris, on my way to England, and I had two days to record there. So I was in the middle of this recording… Lemme see, I had Willie Mabon on piano, Lonnie Brooks on guitar, Dave Myers on bass. Oh lord, I had a line-up from Chicago and I got three numbers to get through for the album and I got this telegram from Wolf. It said ‘I want to see you. If you want to see me, please make it as fast as you can. Get back.’ Because he was dying. So that morning, they picked me up from the studio and they put me on that plane and they had a limousine waiting for me to the hospital.

When I got there, they had Wolf’s eyes taped up. He was already dead. So they allow me two minutes to see my daddy. That’s what they said. My wife met me at the hospital and she took me back home, so the telephone was ringing when we got there. It was the hospital, said oh, they made a mistake. ‘Mr Sumlin, your father just passed.’ I said, ‘You know, I’m sorry lady, but you’s lying’, you know. I said, ‘The man died yesterday.’ And then, after she hung up on me, Wolf’s wife Lillie call. She say, ‘Wolf passed yesterday evening.’ He had something to tell me and he didn’t get chance. That’s what it was…

What do you think he was going to tell you?

I believe he was gonna tell me keep on doing what I was doing, you know, and do it right and do it well. That’s really what I thought he was gonna tell me. He wouldn’t go nowhere without me and I didn’t go nowhere without that guy. And all the records that we’d made – man, he let me put the music to his numbers. Sometime, we would get one number 20 different ways, and more than that, but we always would go back to the first. I remembered, yup!

You’ve been an idol for so many guitarists in Britain…

Yeah, that’s right, that’s right, that’s what they say… It make me feel great. That make me feel good. I tell you what, I have achieved something – you know what I’m talkin’ ‘bout? To make a dent in this music, man. You know, when the people love me, when the world can understand a little bit, where I’m coming from, you know, where I been.

Can you summarise what music means to you?

Hey man, means the world to me. You know, without this music, I don’t know if Howlin’ Wolf would’ve happened. I don’t know what’d happen to me. I got an idea, I wouldn’t be here, you know? Because they talk bout retiring – ‘Man, when are you gonna retire?’ Hey! Sure, I’m 76 years old. I ain’t gonna retire, and I mean, I ain’t sure nobody got out of this thing alive in the first place. No kiddin’, man. Every day I hear about people that’ve died on the bandstand. I ain’t gonna say I’m gonna do it but, you know, if I happen to do, I’d rather be that.

So you have a message…

Oh man, if I had a message – do what you love, do what you like, do anything you like but if you don’t like a thing… look I ain’t gonna tell you ‘Don’t do it!’, you may have to do it. It’s better if you love it but you gotta work, you gotta have a job, you gotta do something to make it, you know? In my book, because I love music this is what it’s gonna be.

I know it. Sooner or later, I believe that it’s gonna happen good. And when I leave here, I tell all these musicians… People ask me the same thing you just do. I tell ‘em like this. If you want something, you like it, and you can be what you wanna be, if you wanna. You got to believe. You got to have faith, man, and keep on doing what you’re doing, but do it right, and do it as good as you can do it. That’s what it’s all about. I know it.

You know what? I learnt so much with Wolf around me, man. When I first got with him, I didn’t know too much but I tell you what… I learnt from Wolf. I recorded with a lot of people – Chuck Berry – but Wolf the one that showed me what to do.