Back in 2018 Prog charted the history of Australian prog rock, from its 1970s beginnings to its development in the 1980s and 90s, through to the currently thriving wave of new and exciting bands who are making waves Down Under and beyond...

In the beginning, there was rock’n’roll. It was raw, it was wild, it was primitive, it spoke to the viscera and the grinding crotch rather than the cerebral cortex. It stripped away much of the esoteric excess of jazz and took what the blues was doing and made it ballsy and fun. And it subsequently ruled the world for the better part of half a century: any rabid rock fan worth his or her salt knows its history.

However, within a relatively brief period of time in the span of rock music’s storied entire history, a highly imaginative and creative subset of rock musicians, who were hungering for newer and more complex sounds, instrumentation and arrangements, emerged from the rehearsal rooms and venues of the world.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the phenomenon known as ‘progressive rock’

or ‘art rock’ was in full swing, led by the scene’s shining stars in Yes, King Crimson, Genesis and Pink Floyd, with the likes of Gentle Giant, Curved Air and Goblin following hungrily in their wake. On the other side of the Atlantic, the scene was simultaneously being spearheaded by Rush, Kansas and Utopia. These musicians and their output resonated with fans’ cerebrums as well as their hearts, souls and nether regions.

Anyone who calls themselves a prog fan knows this history well. What many progressive music fans north of the equator may not know is that while all this was happening, another similar and highly creative scene was operating in relative obscurity on the other side of the planet.

Until the early 80s, Australia was broadly considered to be a large, exotic and inaccessible country down there at the very arse-end of the world. With Men At Work releasing Down Under and the nation winning the America’s Cup sailing event, and then especially with the release of the movie Crocodile Dundee in 1986, the nation rose in the rest of the world’s consciousness.

During the 1970s, however, a very strong undercurrent of progressive rock music was being created in the shadow of the scene’s illustrious international luminaries.

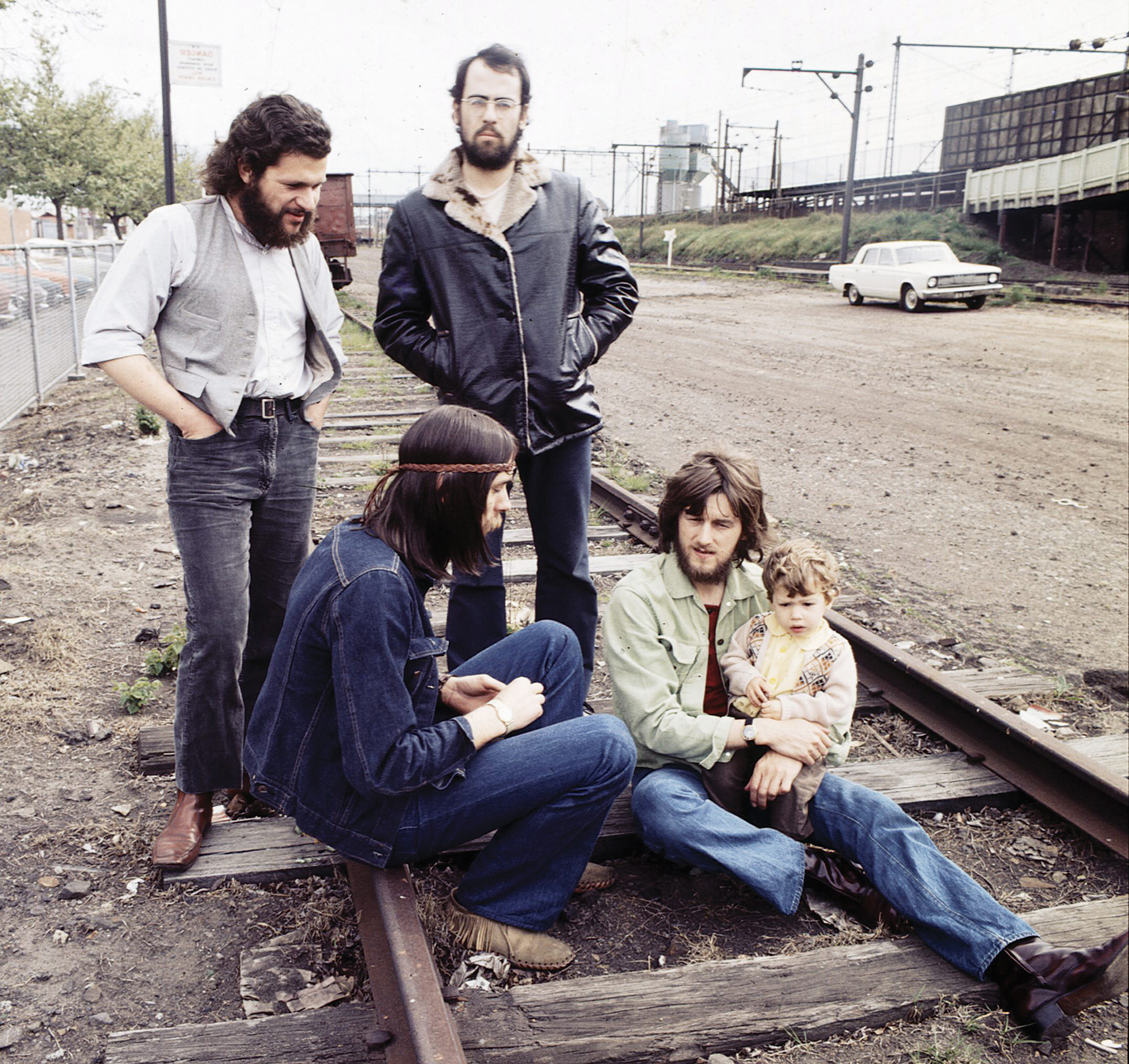

This was arguably spearheaded by Melbourne band Spectrum, who were formed by the legend of Kiwi and Australian prog Mike Rudd. Spectrum only lasted for around five years but were extremely prolific during this period (and they also reformed in

the late 90s).

Then there were fellow Melburnians Madder Lake, who were known as San Sebastian in an earlier incarnation; Ariel, another Mike Rudd creation; Ayers Rock, who featured legendary Aussie drummer Mark Kennedy; Perth band Bakery; and Sydney/Adelaide act Fraternity. The latter were notable in that they featured no fewer than three legendary Aussie rock frontmen: Bon Scott, Cold Chisel’s Jimmy Barnes and his brother John Swan.

Speaking of legendary singers, Sydney band Sebastian Hardie (later known as Windchase), who became known as ‘Australia’s first symphonic rock band’, featured a frontman by the name of Jon English, who went on to become a major star of stage and the small screen in Australia. The band released several studio albums, attained some international recognition and supported Yes on their 2003 Australian tour.

Sitting in a grey area between pop and prog were Melbourne’s ultra-quirky Skyhooks and Adelaide band The Masters Apprentices, both of whom attained considerable commercial success in their home country and fleetingly flirted with international stardom. Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt calls himself a fan of the latter and even named a track from his band’s 2002 album Deliverance after them.

Special mention must be given to seminal Sydney band Tully, who were not only prodigiously influential in terms of their music, but also their dazzling approach to the lighting and visuals of their live show. They also became the house band in many of Australia’s adaptations of international musicals, such as Hair.

The 80s and 90s found many of prog’s international heavy hitters honing their respective sounds and going from strength to commercial strength. That period in Australia was a little quieter, although it did see the formation of Adelaide band Unitopia, a formidable outfit that combined traditional 70s-influenced prog rock with jazz and world music elements, with political and environmental themes. They released four seminal records before disbanding in 2012, giving rise to new bands United Progressive Fraternity and Southern Empire.

Other Aussie art-rock, prog and proggy metal acts to ply their trade through this period were Alchemist, Alarum, Vanishing Point (who, while more in the power metal realm, certainly utilised some progressive elements), Perth’s Heavy Weight Champ, Teramaze, legendary Tasmanian tech metal outfit Psycroptic, The Grand Silent System and Pre-Shrunk. These bands kept the Aussie progressive flame alive during this lull before the true renaissance arrived.

Another profound event for the Aussie prog rock scene occurred during the 90s – the formation and rise to prominence of American juggernaut Tool, whose enormous shadow still lies across the Australian prog sound today. Their influence on the Aussie sound cannot be overstated, despite the non-prolific nature of their own output.

The origins of many of the leading lights of modern Australian progressive music can be traced back to the late 1990s, but the true spark was lit in 2001. While they may stretch the definition of ‘prog’ just a touch, blazing a trail out of Brisbane were The Butterfly Effect, releasing their self‑titled EP that year to universal acclaim, and following it up two years later with the iconic debut long-player Begins Here. Mining unique sonic and songwriting territory that was so dark and atmospheric it veritably sent shivers down your spine but was somehow soaring and uplifting at the same time, a whole new sound and a whole new scene was born on the back of those two recordings and the band’s breathtaking live show. It was the modern Australian alternative and progressive rock sound.

The Butterfly Effect’s frontman Clint Boge has vivid and heady memories of that period: “It always felt like an underground scene,” Boge recalls, “even when [Australian nationwide youth radio station] Triple J shone a light on it and we had that purple patch during the early to mid-2000s, where it was like Butters, Karnivool, Shihad and Cog, just a lot of great rock bands.

“It just felt great to be part of an underground scene that was actually getting some love from radio, and the fans just loved it. It was absolutely grass-roots and organic – the people just found us, and that was partly due to the fact that we all just toured like maniacs. That was the defining factor that put Aussie progressive and heavy rock and metal on the map.”

While The Butterfly Effect set things in motion in a major way, the true watershed moment came in 2005. Early that year, Perth band Karnivool released their exalted first album Themata, and a few months later Bondi (Sydney) trio Cog unleashed their own illustrious debut long-player, The New Normal, and the face of Aussie progressive rock changed forever. Rock music fans across the nation stopped what they were doing, pricked up their ears and took notice, and even aficionados across the rest of the globe started to cast a sneaky ear in Australia’s direction.

Both bands channelled Tool, although both certainly put their own individual slant on the sound. Themata is an intoxicating affair, its kaleidoscopic grooves drawing you in while its soaring melodies have you crooning in delight. Its power is subtle but indisputable. The New Normal takes a slightly more raw, more direct approach, although it’s still dark and intelligent, as well as immensely impactful. Its political and social message is understated but undeniable.

And as with Tool, the baton was passed, the influence spread like an Aussie bush fire in high winds, and a slew of bands directly influenced by the sounds, songwriting and vibe of these two titans followed in their path. Arguably the most notable were Brisbane’s Dead Letter Circus, whose phenomenal eponymous 2007 debut EP set them on a course towards national stardom and a rather respectable international following.

One individual was almost single-handedly responsible for creating that distinctive Aussie progressive sound, in a sonic and production sense. Forrester Savell produced Karnivool’s iconic first two records, almost everything Dead Letter Circus have released, The Butterfly Effect’s third and final album Final Conversation Of Kings, and has also worked with such local and international luminaries as Twelve Foot Ninja, Skyharbor, Good Tiger, Sikth, Birds Of Tokyo and many others.

It’s purely in hindsight that Savell realises just how resonant the sounds he was creating were, and just how profoundly those records have influenced and contributed to an entire subgenre and a niche national musical identity. “At the time, when you’re in it, you have no idea you’re creating anything, creating a scene,” he says. “I thought I was just developing my career.

“It all comes from growing up in Perth and just being involved in such a healthy and encouraging scene, and bands like Karnivool, Full Scale, Heavy Weight Champ. I knew all the members of the bands personally, we all went out together socially, and we built the scene on the back of that camaraderie.”

From Perth, Savell was heavily involved in the spreading of the scene and that camaraderie across the rest of the nation. “We all sort of pushed eastward at some point,” he remembers. “I moved to Melbourne with Full Scale and we encouraged all those bands to come over and do tours and introduced them to the east coast bands like The Butterfly Effect and Cog and getting them all on tour together. We just continued on that same kind of attitude, creating a scene.”

On the back of such enthusiasm and momentum, many new bands sprang up and took their place on the circuit. There were Melburnians Jericco, who took what Karnivool were doing and infused it with an exhilarating Middle Eastern flavour. Twelve Foot Ninja are similarly eclectic, although their beef is a head-spinning and seamless amalgam of jazz, funk, ska and pop, juxtaposed with their pounding but groove-laden rock and metal. Mammal were an absolute tour de force in a live sense, and were being touted as Australia’s Rage Against The Machine before personal differences tore them asunder in 2009.

One of the most underrated pieces of work to come out of that bountiful late-2000s era was the debut album from Melbourne band Sleep Parade, Things Can Always Change. Similar to Themata, its captivating and powerful melodies, atmospheres and soundscapes take the listener to another musical plane. So much so that the band caught the ear of Porcupine Tree’s Steven Wilson, who hand-selected the band to be the support act on Porcupine Tree’s two Aussie tours in the early 2010s.

Other bands to rise to prominence during that late-2000s, early-2010s period were Brisbane’s unique and mesmerising Caligula’s Horse, 70s-influenced Melburnians Closure In Moscow, Sydney-based percussive-driven powerhouse Breaking Orbit, Toehider (whose main man Mike Mills was hand‑picked by Arjen Lucassen to sing and play on multiple Ayreon albums), Sydney post-rock instrumental legends sleepmakeswaves, world music-influenced chaos merchants Alithia, Byron Bay’s Engine Three Seven and more. Heavier progressive sounds were being provided by the likes of Circles, Voyager, Ne Obliviscaris, Hemina, Northlane, The Eternal, The Amenta, Sydonia, Helm, Chaos Divine, Bushido and many others.

This period also saw a strong undercurrent of more experimental sounds emerge from the underbelly of Australia’s music scene. Following on from and inspired by what The Grand Silent System were doing in the late 90s and early 2000s, instrumental and vocally orientated acts such as Xenograft, Ennis Tola, Anim8, Geamala, Glasfrosch, Mushroom Giant, Meniscus, Head Filled Attraction, Colditz Glider and A Lonely Crowd threw convention to the wind, did whatever the hell they wanted and created some astounding sounds and amazing music in the process. Active or otherwise, all of these bands have music online that is well worth tracking down.

Now, a second renaissance period has begun. Several of the bands that had previously announced splits, or at least hiatuses, have returned to the fold. The Butterfly Effect, Cog, Mammal, Superheist and others have all come back after having patched up former differences and found that there’s still massive demand for their sounds and their live shows across the nation. Boge could not be more excited about this development.

“Now with the re-emergence of all these bands, it has definitely put a spotlight

back on our genre,” Boge says. “And also, the fans are still there, they still want

this music and they’re still frothing to see these bands come back around, which

is amazing.

“And you know what? I don’t think there are too many other genres of music that have fans so loyal and devoted like this, so credit to them, credit to the bands who’ve come back and credit to the bands that have stuck around and kept the scene going.”

There’s also a ridiculously strong current crop of bands plying their trade across the nation. Acolyte are a Melbourne-based progressive group who draw influence from such diverse sources as Pink Floyd, Europe and Karnivool, and channel it into compositions that are long, complex and memorable.

Melbourne’s Figures are heavier and more direct in their proggy alternative approach, although no less catchy. Transience pack a hell of a wallop as they slam out their enthralling, heavy, modern progressive rock songs. Orsome Welles are both quirky and bone-crunchingly heavy, and vocally unique. Kettlespider combine old school prog rock with more modern elements to create a compelling, live‑wire vocal-free sound. To name but a few.

Running in parallel to the mainstream of progressive music in Australia is an exuberant tech guitar instrumental scene, led by Sydney wunderkind Plini. The young guitar slinger has dazzled the world in recent years with his soaring and intricate instrumental guitar compositions, and his 2016 album Handmade Cities was described by none other than Steve Vai as: “One of the finest, forward thinking, melodic, rhythmically and harmonically deep, evolution of rock/metal instrumental guitar records I have ever heard.”

Powering along in his wake are Sydney shredders The Helix Nebula, with whom Plini’s band share a number of members; Melbourne whizz-kid Rohan Stevenson, who goes under the moniker I Built the Sky; Melbourne prodigy James Norbert Ivanyi; and bands like Scoredatura and The Omnific, whose line-up consists of two bassists and a drummer, and who delve quite deeply into jazz and fusion-esque sonic territory.

There’s a veritable smorgasbord of stunning sounds accessible to the rabid Aussie prog fan right now, with the message slowly but surely reaching out across the globe as well, and it all bodes well for the future. One man at the epicentre of Australian progressive music, a man who will play a major part in pushing the sound forward in 2018 and beyond, is aficionado and entrepreneur Eli Chamravi. Already having run his booking and management agency Wild Thing Presents for almost six years (the agency responsible for running Australia’s most prestigious progressive music festival Progfest), Chamravi recently announced the launch of his own record label, Wild Thing Records. The label have already signed Melbourne djenty progressive metallers Circles, a band with several international credits to their name, and this is just the beginning.

“We anticipate having a number of records out by the end of the year,” Chamravi says. “We’ll be signing both local and international acts. The label will give more weight behind building acts in Australia and also bring up-and-coming acts from overseas to tour – tours that may not otherwise have been financially possible.”

The creation of the label reveals much positivity about the future of Australian progressive music, and a strong determination to push it to its rightful place of prominence across the nation and around the world. “I think it can help this Aussie prog scene become much stronger, healthier and more united,” Chamravi says.

“We’re extremely optimistic. It’s not the biggest scene or genre in the world, but the people that are involved in it – the punters, promoters, crews, media personnel, photographers and reviewers – are extremely passionate about it. It’s an extremely welcoming scene. The thing I like about it the most is that we have people of all ages, all ethnicities, genders and so on: everyone comes, everyone has a good time and we always get repeat fans at all the shows. The community vibe is amazing and that’s what gives me massive hope for the Aussie prog scene.”

Of course, there are still many struggles facing Aussie bands of any ilk wanting to spread their notoriety across the country and the world. Australia is a massive island continent with a low population base, relative to many other nations across the planet, and so it’s extremely expensive to tour, with enormous distances to cover between cities. Then there’s the nation’s extreme isolation from the rest of the world. Bands taking on the enormous task of transporting themselves, their gear and their crews to Europe, the US or elsewhere often return to Australia many thousands of dollars in the red.

Several bands have taken the controversial step of undertaking Patreon campaigns to keep themselves afloat and working. These campaigns take the concept of regular crowd-funding a step further, having the band’s loyal fans fund their activities in a more ongoing fashion, in the form of monthly contributions. Most notable of these bands has been extreme progressive metallers Ne Obliviscaris.

The well-documented woes of the music industry as a whole certainly don’t help either. However, the passion for the music and the desire to create a career in the industry drives these determined bands to write better songs, release more epic albums, put on more impressive live shows and take their music and message to the world.

From its early, humble but hopeful beginnings, right through to a scene today that is growing relentlessly in profile, prominence and confidence, Aussie progressive rock and metal is a small but extremely vibrant movement that’s well worth your attention.