You think you know Corey Taylor?

Sure you do. He’s one of the biggest characters in our world. Metal’s Great Big Mouth. The man who’s spawned a thousand memes. For 20 years, he’s told us exactly what he thinks… about everything. We’ve watched him take on the haters, rant about reality TV, and even knock Kanye West down a peg or two…

So when he announced his debut solo album, CMFT, we thought it was safe to assume it’d fall somewhere between the dark depths of Slipknot and the metal- tinged anthemia of his other gig, Stone Sour. On July 29, Corey released two singles to kick things off: the bright, melodic Black Eyes Blue, and hubristic cut CMFT Must Be Stopped. As the video for the latter hit the internet, shocked Maggots howled into the void. There were fire-breathing, leather-clad women. Ten-foot-high flashing letters spelling out his initials. Cameos from anyone who’s anyone in metal, from Lars Ulrich, to Rob Halford, Babymetal and Manson. A verse each from hip hop artists Tech N9ne and Kid Bookie, and then Corey himself, bare chested, a championship wrestling belt across his shoulder, rapping over a swaggering bop that could soundtrack a bloody Royal Rumble. Understated it is not.

Online the debate raged, fans unable to decide if he had just entered an exciting new era or had just dropped the stinker of his career. Today, Corey hoots with laughter at the response. “All the pretentious people can’t stand it. Or more to the point, people who hate fun,” he says with a grin. “And all the people I thought were going to hate it, loved it. I love the fact I’m pissing in the face of the elitists.”

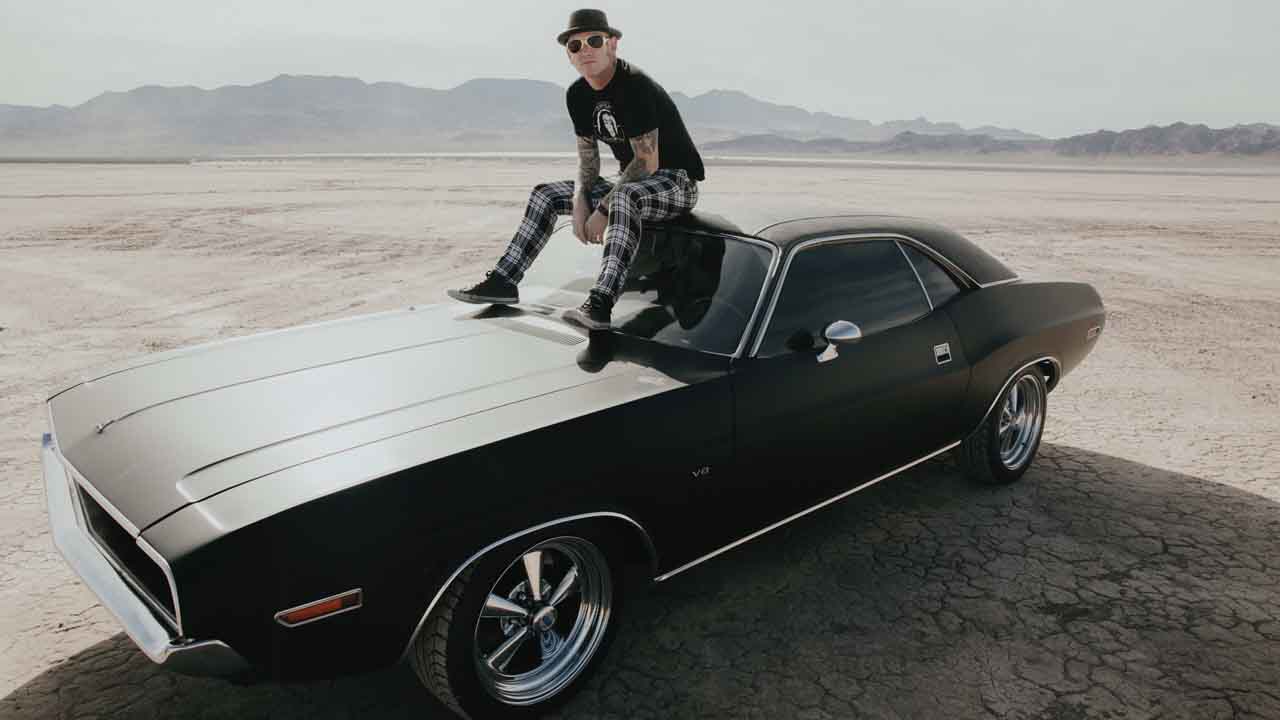

You don’t call your solo album Corey Mother Fucking Taylor unless a) you’ve got balls or b) you’re looking for a reaction. In Corey’s case, it’s both. “It’s basically me taking the piss out of my public persona and making fun of people who think they know exactly who the fuck I am,” he declares. From the outset, he makes it clear this album is a reinvention: he wants to challenge our preconceptions of who Corey Taylor is.

Saying that, when he calls us today from his home in Las Vegas, a city he’s lived in for 12 years and that perfectly suits his larger-than-life personality, it takes about two minutes for his infamous soundbite syndrome to kick in. “It was wall-to-wall assholes,” he says, recalling his wedding night with wife Alicia Dove, which he spent at the ARIA Casino on the Strip, a tourist hell he usually avoids like the plague. “I was like, ‘God. I can’t wait to just go home.”

- Slipknot masks: The Definitive History Of Every Mask

- Slipknot's ultimate mixtape

- Nu metal songs: The 40 best of all time

- “The media want the bullsh*t and drama”: a tense audience with Slipknot

So far, so Corey, but the music comes as a surprise. When COVID-19 struck, while most people spent early lockdown overeating and watching Tiger King, Corey headed to The Hideout Studios on the outskirts of Vegas. There, his solo album was recorded, under strict social distancing, with producer Jay Ruston and a bunch of mates: guitarists Zach Throne and Stone Sour’s Christian Martucci, drummer Dustin Robert and bassist Jason Christopher. Together, they’ve created an album that nods to the plug-in-and-go essence of rock’n’roll, with big choruses and uncomplicated, muscular bluster aimed straight at festival stages that makes nods to country and punk along the way.

“I didn’t really have a clear vision [for the record] until I started putting the songs together,” Corey says. “And by ‘putting the songs together’, I mean figuring out what we were going to put on the album, because some of these songs go all the way back. Kansas is about 15 years old. Samantha’s Gone is 13 years old. I can remember writing the first two verses of HWY 666 in 10th grade.”

Over the years, Corey had built up an arsenal of tracks that didn’t quite fit with either Slipknot or Stone Sour, but surprisingly, he didn’t seriously consider a full solo project until recently. “People kept asking me about it; it came up in every interview and with every fan that I talked to,” he says. “For a while it was like, ‘No, how greedy can you be? I’ve got two great bands. I get to do pretty much any guest appearance I fucking want. Then the more I thought about it, I thought, ‘I’ve got all these songs that are really good. What am I going to do with them?’”

Between his Slipknot and Stone Sour commitments, Corey has always been too busy to dedicate time and energy to a solo project – but there’s another reason why it’s taken him so long to go it alone. Until recently, he simply wasn’t in the right headspace. He’d spent years battling personal trauma. “I couldn’t have made this album 10 years ago,” he says grimly, “because I was right in the eye of the storm.”

When we caught up with Corey last year, we found the beleaguered singer in fire-fighting mode. Slipknot were on the cusp of releasing their eagerly awaited sixth record, We Are Not Your Kind, but things inside the camp were looking decidedly turbulent following a period of change and instability. Founding member Chris ‘Dicknose’ Fehn had left the band under a cloud of animosity and, most tragically, percussionist Shawn ‘Clown’ Crahan’s daughter Gabrielle had passed away, aged just 22.

Corey, too, was in bad shape. Not only was he recovering from double knee surgery, he was promoting a record that catalogued one of the most difficult times of his life. In 2017, he had spiralled into a deep depression following a bitter split from his second wife, Stephanie Luby, but due to touring commitments for Stone Sour’s sixth album, Hydrograd, he hadn’t had time to truly process it. To add to the emotional weight, just before the release of the album, Corey had appeared on US TV show The Therapist, where he opened up for the first time about being sexually assaulted as a child. Unsurprisingly, he had spent the Hydrograd tour “shell-shocked and trying to find out who the fuck I was”.

When it came to recording We Are Not Your Kind with Slipknot in early 2019, Corey poured every drop of disillusionment, pain and anger following his divorce into the music, a catharsis he now describes “working through a sort of PTSD”.

“I’ve been reticent to go into too much detail about my prior relationship but it was really dark, really toxic and it ended badly,” he says. “I decided to purge. I had to. I had to let everything out and not hold anything back. Because I was able to do that, I was able to give substance and weight to the way I was feeling, the things I had gone through, and all of these mental issues that came in the wake of that; I was able to really sort them out properly and put them down and move on.”

Having weathered the storm, Corey can now talk about things with a sense of detachment. He admits he stayed in his previous relationship far too long, knowing he couldn’t save it, but a stubbornness he now looks back on as “mid-western stoicism” prevented him from packing it in. “I didn’t want to feel like I’d failed twice, even though it takes two to fuck something up,” he says. “I didn’t want to feel like I hadn’t given it everything I could. The good thing that came out of that marriage is my daughter. That’s one thing I can be thankful for from that relationship. Nothing else.”

As painful as break-ups are, they are rarely a complete waste of time, and Corey admits it’s been a learning process. “Sometimes you don’t have to stick it out. Sometimes if your gut is telling you things are bad, listen to your gut. I ignored it for a while trying to do the right thing – whatever the fuck that is. Sometimes the ‘right thing’ isn’t the right thing for you.

It took a long time before he felt like himself again. He went to therapy, which helped him to identify and eradicate toxic presences in his life, including an addiction to social media. Back in 2017, Corey would frequently engage in conversation and arguments with random fans on Twitter, while plastering his private life across Instagram, sharing everything from gym selfies, to videos of himself cooking and his daily pilgrimage to Starbucks. Behind the veneer, though, he reveals he was actually seeking an escape.

“It was, for the longest time, my only source of solace,” he says. “Because my personal life was so barren of appreciative feeling, the only place I felt I had any real contact with people was on social media.”

It’s now been a year since he used it, and it’s been brilliant for his mental health. “It was one of the best things I could have done,” he says. “I have a friend of mine who runs my Instagram and Twitter. I treat it like an extra layer of promotion now. I tell him to put stuff up, but I stay away from it and I don’t read the comments. It’s such a trigger for my addictive personality.”

Speaking to Corey now, he is back to his usual, brash self; energetic, excitable and brimming with positivity for his life and new music. In October 2019, he married Alicia Dove, leader of dance troupe Cherry Bombs – the ladies who are breathing fire all over the CMFT Must Be Stopped video – who he began dating when the Bombs, along with Steel Panther, supported Stone Sour on their late 2017 US tour.

“There was an instant chemistry that popped but I was in such a gnarly spot that I wasn’t ready to date anybody,” he says, recalling the occasions he and Alicia had met prior to the tour. “It was hard to walk away from each other, but then fast-forward to the tour, when we saw each other it was just as strong as the last time we’d talked. The second we got around each other, people in the room could feel it. By the end of the tour we were together and we’ve been together ever since.”

Unequivocally, he credits the relationship as the reason for his current state of mind. Alicia attended Corey’s therapy sessions with him and together the pair worked through his darkness, eventually emerging from the other side.

“She could be the most fun person I’ve ever known,” he declares happily. “She smiles from the second she wakes up to the second we go to bed. We laugh constantly. When you have someone who is that excited about life, it’s infectious. I realise that that’s the way I used to be a long time ago, and having that reminder in your face reinvigorates the way you look at life.”

Had COVID-19 not wiped clean the gig calendar for every band on the planet, at the time of writing this we would have been six days away from Slipknot’s first-ever UK Knotfest. Instead, this is the longest Corey has been off the road in 20 years, although he admits he’s wound up enjoying the break. “It’s given me a chance to do exactly what I wished I could be doing while I was on the road. I’ve been able to spend really good time with my kids,” he says.

He and Alicia have finally had time to move properly into their Vegas home, which has been full of unpacked boxes since their wedding last year, while Corey has relished the chance to hang out with his son Griff and even attend a school dance recital with his youngest daughter Ryan, as Nevada’s COVID restrictions eased over the summer. “Obviously I’m not a dancer but we had so much fun,” he smiles. “We had a good time and we were able to get a video of it and we watch it all the time.”

Constant touring has had its repercussions, though. As the topic of conversation turns to his children, and his eldest daughter Angeline, Corey’s cavalier facade fades. “She and I aren’t really close,” he says quietly. “I don’t want to say we had a falling out, but we just kind of drifted apart a few years ago. I wasn’t there when she was born. She was born early on and I was already at work when that was going on. With Griff it’s different, though. I was there from day one. As well as with Ryan.”

When he speaks again, the sadness in his voice is palpable. “It’s difficult. It’s a tough thing to deal with, but all you can focus on are the ones you have, the ones that are right there, and hope that the other one is doing OK.” He pauses. “I definitely miss her.”

Still, Corey is holding on to the positives. Having spent most of his life battling some degree of depression or addiction, he’s now been sober for 10 years. Having been through the ringer in the last few years, he has finally reached a happy place, and you can hear that in the new music. “My whole mindset has changed,” he says. “Before I was so full of piss and vinegar and angry about shit, I would crack off about everything. I really started to go, ‘Who gives a shit? Does it really matter?”

Does he mean the salad days of ranting about the Kardashians and “inferior music” are over? “It doesn’t mean I’m not still a prick about it,” he laughs, and just for a moment, the curmudgeon of old raises its head. “But I’ve let go of the energy it takes to be angry about it. To me, at the end of the day if someone’s happy, then good. There’s way too many things that we should be fighting and trying to make better, and way too many things that are trying to tear us apart. If there’s a handful of things that make you happy then who am I to fucking question it? And because I’ve let go of a lot of that negative bullshit, it’s made me happy too.”

There’s little evidence of old baggage on CMFT. In a back catalogue that spends most of its time raking back over past regrets, this is the first time Corey has looked forward to the future, his vision clear and unclouded by demons that have been a constant presence in his life until now. “I re-evaluated my focus on my priorities,” he says. “I’ve been able to reconnect with friends. Dedicated myself to being part of my kids’ lives. My marriage. Going through what I did, made me appreciate what I have. Letting go of the weight of all that shit, I was able to transfer this positive energy and excitement into these songs. It’s almost like a new lease of life.”

Published in Metal Hammer #340