Everybody needs to start somewhere. For Geoff Downes, that break came in the orchestra pit at London’s New Theatre. It was 1975, and the 23-year-old Downes was playing keyboards in a brand new stage show. And his unlikely paymasters? Pointy-nosed kids’ TV characters The Wombles.

“It was my first job after I finished music college,” says Downes, northern accent undiluted after more than 40 years on music’s frontlines. “I answered an ad in Melody Maker looking for musicians for a theatrical production, and I got the job. It turned out to be the stage version of The Wombles.”

And did he have to wear a costume? “Thankfully I didn’t,” he says with a laugh. “They were bloody unhealthy things.”

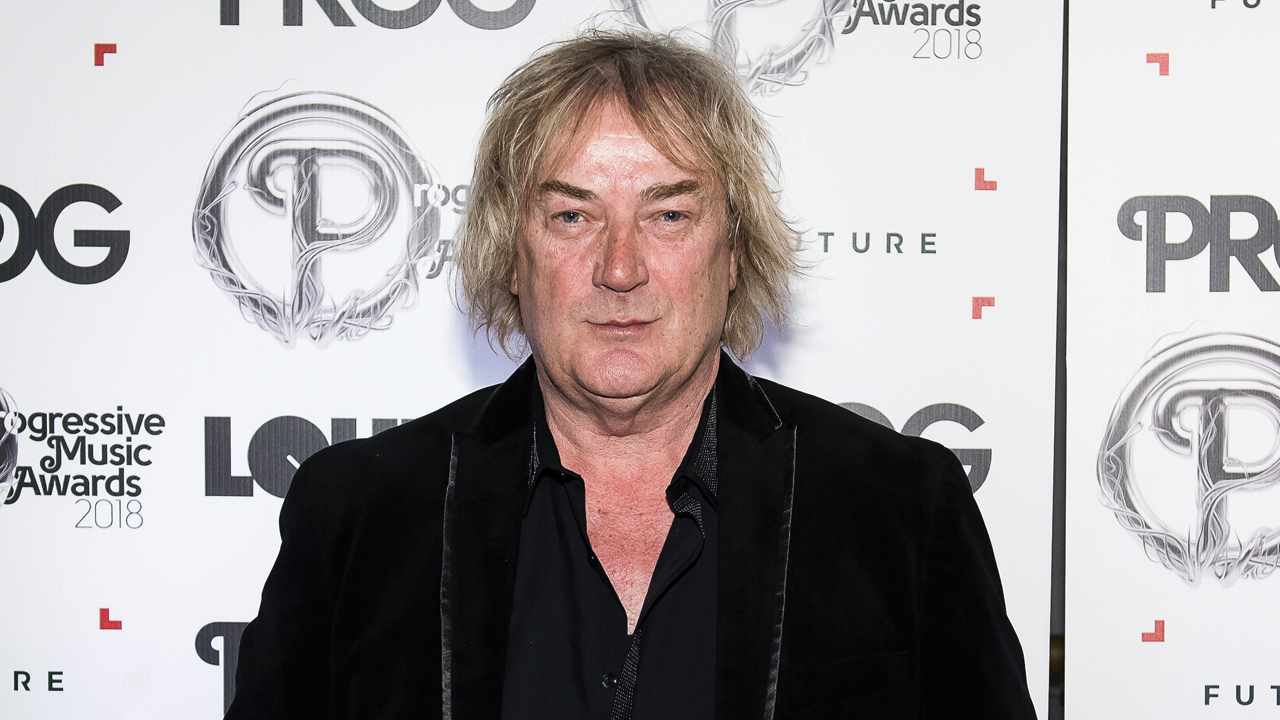

Downes has come a long way since rubbing shoulders with Uncle Bulgaria and Madame Cholet. His journey has taken him from new wave pop stardom with The Buggles to prog’s upper echelons as a two-time member of Yes, via a stint as a bona fide rock star with multimillion-selling 80s arena‑prog titans Asia.

The list of people he’s worked with over the years reads like a Who’s Who of prog royalty: Chris Squire, Steve Howe, Greg Lake, Carl Palmer, John Wetton. But his most enduring relationship has been with Trevor Horn, whom he first met as a member of disco singer Tina Charles’ backing band. If Downes and Horn haven’t quite been constant musical companions, they’ve taken many of their most significant steps together.

“I’ve never, ever argued with Trevor about anything,” says Downes. “Not once. Some writing partnerships only work if there’s some conflict, but we’ve never had that. We spent more time defending our own ideals from everybody else.”

Today, Downes shows no sign of slowing down. He’s currently seven years into his second stint as Yes’ keyboard player, while a fruitful collaboration with British-born, American-based singer-songwriter Chris Braide has produced three albums under the name Downes Braide Association. Unlike some of his flashier, more combustible contemporaries in the prog world, Downes’ course has been relatively free of turbulence.

“I’m a non-confrontational kind of person,” he says. “I don’t get upset by criticism. I’d rather be a catalyst to work with than someone who is in people’s faces. I’ve never actually fallen out with anybody. I don’t think there’s a musician I’d say I’ll never work with again in my life.”

But neither is Downes the quiet man of prog. “Oh, I’ve got some ego, I do like to pose a bit sometimes,” he says with a grin as he prepares to look back on his 40-plus years bridging the worlds of prog, pop, rock and, well, Womble music.

Which band first made you want to be a musician?

The light bulb moment was probably when I jumped the train to go to the Isle Of Wight festival in 1969. The Nice were playing and I saw Keith Emerson. That was probably one of the biggest things that led me along the road of being a keyboard player. I was really interested in the keyboard-driven bands that were around at the time – Procol Harum, the Canterbury bands. Anything where the keyboards played a dominant role.

You were born in Stockport and studied at Leeds College Of Music. When did you decide to move to London?

A friend of mine who I was at college with went there in advance. He lived in a big house in Clapham, south-west London and invited me to move in. Weird place, loads of odd people. Chrissie Hynde was living there. Nick Kent, the journalist from NME, had been living in the room before me. There were a few hypodermic syringes about. It was a pretty scary place.

Where was your head at musically at that point?

I’d moved away from prog. I was more into the disco scene at the time – Earth, Wind & Fire, people like that. Steely Dan too. It did have an influence on me over what came later with The Buggles.

Where exactly did you meet Trevor Horn?

There was an ad in Melody Maker saying, “Keyboard player wanted for chart act.” I went down to this rehearsal place in Bermondsey. I had a Minimoog and a Fender Rhodes in the back of my battered old Ford Escort estate. It turned out that it was for [disco singer] Tina Charles. Trevor gave me the job straight away. He said it was because he was impressed that I had my own keyboards. I’d actually borrowed them from a friend.

What were your initial impressions of him?

He seemed a good guy, pretty sincere. He didn’t feel like a long-lost buddy – it was more of a working relationship. But there was a bond between us. We were both a couple of northern lads trying to make it in London, struggling against the southerners. I think he liked the fact that I was a bit of a perfectionist and wanted to get everything dead right.

You put together The Bugs, who became The Buggles, not long afterwards. Was there a grand plan behind it?

It was just something we drifted into. Trevor had started to get these small production things and he used to rope me into them. At the same time I was doing ad jingles, just bread and butter stuff, and I’d get him involved in those. The Buggles mainly just grew out of that.

You came across like a pair of mad scientists locked away in a laboratory. How accurate a description is that?

In many ways that’s how we saw ourselves. We were the backroom boys. Our motto was, ‘The Buggles will never go live.’ It was only ever going to be two studio creatures beavering away.

And then Video Killed The Radio Star came along and everything changed…

I remember a very rudimentary demo we did and even at that point, there was something extra special about that song. But Trevor and I took the demo around to every single record label in London and got knocked back by them all: “Nah, don’t think so, it’s okay, but we just signed The Corgis.” It just so happened that my girlfriend at the time was working for Island. She played it for her boss, and it got to the ears of [Island boss] Chris Blackwell, who said, “You’d better sign these guys straight away.”

Did you enjoy being a pop star?

I did. It was something I’d aspired to, being on Top Of The Pops and all that stuff. So when it actually arrived, I took it in my stride. Having a number one record around the world was great. Trevor didn’t take to the teen mag stuff that went with it – he wasn’t really happy with that.

But within a year, both you and Trevor ended up in Yes. That was quite some left turn. How did it happen?

We were being managed by the same company and we’d ended up writing our second album in the studio next to Yes. Well, it was really just Steve [Howe], Chris [Squire] and Alan [White] – they’d just come back from Paris after the ill-fated sessions with Roy Thomas Baker. They wandered in one day and said, “Have you got any songs that might be suitable for us?” So we put together a couple of ideas and started playing them. We just carried on like that and eventually just sort of morphed into them.

What was the mood like when you joined?

They were slightly confused about what direction they were going to go in, because they were just rehearsing backing tracks at that time. They were playing some fantastic music, but it didn’t have any keyboards or vocals on it. We were the ideal thing to come along to them at that time and help carve a new direction on the Drama album.

Not everyone saw it like that. You were booed on the subsequent tour…

Oh yeah. There’s no doubt about that. The Americans were much more accepting – they were so stoned they didn’t really care who was in the band. But people were much more cynical in the UK: “Oh, The Yeggles have spoilt it all.” There was a lot of animosity towards us. I remember we were doing a gig in Brighton and halfway through the keyboard solo, someone shouted out, “Rick Wakeman!” in the middle of it.

Was that demoralising?

It was at the time. And ultimately it had a destructive effect. Chris thought that maybe we weren’t going anywhere with it. I think he was looking to do something else at that point. After the last show, at Hammersmith Odeon, it just dissolved. So I went back to working with Trevor on the second Buggles album. And then that’s when I got the call from the management, saying they were putting together this new band, Asia.

What was the idea behind Asia?

The plan was to offer a Yes-type alternative at a time when Yes wasn’t operating. The idea had been floating around a couple of years earlier, with Carl [Palmer] and John [Wetton] and, I think, Rick Wakeman or Eddie Jobson. Originally Asia was going to be

a five-piece. That’s what the label wanted. We auditioned Robert Fleischman, who was briefly the singer in Journey. Trevor Rabin came over. He didn’t get the job because I don’t think Steve would have been happy with a second guitarist floating around. John was singing the vocals while we were looking for this extra person, and eventually we just turned around and said, “John sounds great, we’re sticking as a four-piece.”

The first Asia album was a huge success on the back of the single Heat Of The Moment…

That nearly didn’t end up on the album. It was an afterthought. We were going to lead off with Only Time Will Tell, but the label said, “Do you have anything else?” So John and I came up with Heat Of The Moment in one morning. Literally, the bones of the song were written in maybe a couple of hours.

What was it like being in the eye of the hurricane?

The massive success did offer up some problems. It was a big gravy train for a lot of people – management, the record label. People start to try and pull you in different directions, starting picking people off for their own ends.

It was a band made up of four successful musicians. Did you have egos to match?

I wouldn’t say so. Everyone had respect for each other. But then John and Steve weren’t really seeing eye to eye over a lot of things. It wasn’t fraught, they were just different personalities. Carl and I were more middle ground in that respect. I think that original line-up was always going to fall apart. We’d all come in at a higher level. We didn’t have to do our time scrubbing around the northern club circuit in the back of a transit van. It was no surprise when it started to change.

Asia went on hiatus after 1985’s Astra, and then you released your first solo album, The Light Program…

After Astra, we’d lost the confidence of the label, we didn’t have Steve on board and John wasn’t really happy with the way things were going. I had this idea to do something with all these synthesisers I’d got and the technology I worked with.

That’s when I came up with The Light Program.

You say “all these synthesisers”. Just how many synthesisers did you actually have?

Oh, an astonishing amount. I must have had 40 different kinds of keyboards at that point. Most of them were in storage a lot of the time. But I’d been in three huge projects in a row, and I wanted to do something that was just me.

Did you enjoy working on your own?

It was interesting but I wouldn’t say totally satisfying. It was an experimental time and I enjoyed making up sounds and trying to emulate other instruments. But you can come up with some of the best work when you’re collaborating with other people. I’ve been lucky to work with some of the best musicians in the world, people like [ex-Deep Purple bassist] Glenn Hughes, Greg Lake…

You worked with Greg when he temporarily joined Asia in 1983, then again in the late 80s on an aborted collaboration. What was he like?

He was difficult to work with. He was a good guy, no doubt about it, and a fantastic musician and a fantastic singer. But he was very much a perfectionist. It wasn’t a very productive collaboration. We only wrote about six songs in six months. He didn’t want to sing one day or do this the next day. That project never had the legs.

You had a much more productive relationship with John Wetton. What was he like?

John was a blood brother to me, but he was a very enigmatic character. At times he was very insular, but then at others we’d talk for hours about football and politics. It’s well-documented that he had a lot of problems with alcohol over the years, but I never fell out with him. We never had cross words. He’d always take it out on somebody else. And he was a brilliant bass player. He was in the league of Chris Squire.

Chris Squire casts a big shadow over two very distinct parts of your career: your original stint in Yes and when you rejoined in 2011. What are your own memories of him?

Chris was the guy who invented how to live a rock’n’roll lifestyle and be a fantastic musician – he could do the two things together. He was a great guy socially. On the Drama tour, we had a private plane and he used to turn up wearing a very smart jacket and a pair of underpants, because he was late getting up at the hotel. That was Chris all over – they used to call him The Late Chris Squire. I know that frustrated people. Bill Bruford was super critical of him for being late all the time, but I just accepted it.

Can you remember the first gig you played after he died?

I can. It was strange, because I always got comfort from looking over at his side of the stage and him giving me a little wink, and that wasn’t there. Not only was he a big guy in terms of his size, but his presence was huge.

When Chris was ill, did you think he’d get better?

We did at the time. He had a very aggressive form of cancer, but at the same time, he was in a very good facility in Phoenix, one of the top cities in America for medical schools. We felt that maybe he had a chance. But unfortunately it took a downward turn quite quickly. And at that point everyone thought the worst.

The prog world lost Chris Squire, Greg Lake, John Wetton and Keith Emerson within the space of 18 months. How did that affect you?

It has been a bad few years, for sure. It does make you look at yourself and your own mortality, and you think, “Well, it’s going to happen one day.” By the same token you look at the achievements of all those great musicians and the impact they’ve had on people.

Right now, you’re firmly back in Yes. It’s been a fairly turbulent few years, what with Chris Squire’s death and Jon Anderson, Rick Wakeman and Trevor Rabin launching their own version of the band…

People have said to me that Yes is like a dysfunctional family. It seems to stumble its way forward with some high moments and some low moments. It runs essentially on the dedication of the fans who have followed every twist and turn. But there’s a general consensus that Yes will carry on and make new music and whatever.

Right now, you’re firmly back in Yes. It’s been a fairly turbulent few years, what with Chris Squire’s death and Jon Anderson, Rick Wakeman and Trevor Rabin launching their own version of the band…

People have said to me that Yes is like a dysfunctional family. It seems to stumble its way forward with some high moments and some low moments. It runs essentially on the dedication of the fans who have followed every twist and turn. But there’s a general consensus that Yes will carry on and make new music and whatever.

It seems like there’s tension between the two versions of the band. Is there?

Any real direct confrontations have hopefully been nipped in the bud. As time has progressed it’s become less critical. When they first came out they were pretty gung-ho – they were making a lot of comments in the press which were not very pleasant, calling us The Steve Howe Tribute Band. A lot of it was unnecessary. For the most part, we’ve attempted to keep the high road and not get involved too much with slagging them off.

Have you spoken to Rick or Jon?

No. The last time I saw Rick was at Keith Emerson’s memorial. He was perfectly decent, even though he wasn’t particularly enamoured with our version of Yes. I’ve very rarely spoken to Jon Anderson in my life. I think I’ve only met him once.

If you were in the same city as them on a night they were playing a gig, would you go and see them?

Probably not, no. I don’t think that would work. But they do their thing, they’ve got their own agenda going on. They’re not getting in my face. That’s all I’m particularly bothered about.

Do you ever wish you were more of a showman, like Rick or Keith Emerson?

No, I don’t. I enjoy being an integral part of something bigger rather than being a singular personality like that. I don’t think I could pull it off anyway. I know my limitations in that department.

What’s the secret to staying in demand for as long as you have?

I don’t know. I suppose I like the camaraderie of being in a band. There’s a point where you really don’t need to fall out with people, particularly when you’re my age.

Who is the biggest pain in the arse: singers or guitarists?

Singers are difficult, but then they’ve got the job of being at the front. I don’t mind guitarists. They just do their own thing and pose around.

Do you look back and think, “I’ve not done too badly?”

I could sit in the garden or go in my studio and look at the gold records on the wall and go, “It didn’t work out so bad, did it?” But I’m not one to rest on my laurels. I like to challenge myself. It’s been very interesting being with Yes. We’ve done a very varied set each time we’ve come out. That’s been interesting for me. It keeps you motivated.

If you had a chance to speak to that 23-year-old guy in the orchestra pit at the Wombles stage show, what piece of advice would you give him?

[Laughs] I’d tell him to keep on wombling.