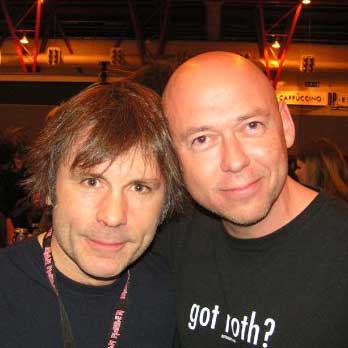

The game is over. In these four words, from the title track of Marillion’s debut album Script For A Jester’s Tear, there’s now a new meaning for the man who sang them so many years ago. “The boy called Fish” – as he jokingly refers to himself – will turn 60 on April 25, 2018. And when that landmark arrives, he will be finished with the game he has played for more than 30 years, first with Marillion and then as a solo artist: making records and touring with a rock band.

The long goodbye-to-all-that has already begun. This summer, Fish completed his Farewell To Childhood tour, in which he performed Marillion’s classic concept album Misplaced Childhood in its entirety for the last time. And he has the next two years planned out. He has, he says, “one more album in me”. The album’s title will be Weltschmerz, a German phrase translating as ‘pain of the world’.

After its release in early 2017, he’ll tour with a show featuring both Weltschmerz and the last album he made with Marillion, Clutching At Straws. And then there’ll be a final tour in 2018, after which, he says, “the electric touring band will be rolled up”.

What all of this represents for Fish is the end of one chapter and the beginning of another. “I’m not retiring,” he says. “But it’s time to explore something else – to move into a different area of creativity. There are screenplays I’ve always wanted to write, and that elusive autobiography. The truth of the matter is that I’m a writer who can sing, rather than a singer who can write.”

Whatever the future holds for him beyond 2018, Fish has had a long and distinguished career in music. With Marillion he made four of the greatest progressive rock albums of the 80s. And while his subsequent work has been more erratic, there have been moments of brilliance throughout, from a classic solo debut, Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors, in 1990, to his most recent album, A Feast Of Consequences, in 2013 – acclaimed by Prog as “one of the most powerful pieces of music released under Fish’s name”.

It’s a career Fish describes, with a dry laugh, as “an interesting journey”. Speaking to Prog from his home in Haddington, East Lothian – the small town in which he has lived ever since his exit from Marillion in 1988, and a place not far from Dalkeith, where he was born – the big man discusses his life and work with remarkable candour.

He recalls how an introverted teenager named Derek William Dick first fell under the spell of prog. How the success of “the Marills”, as he calls them, turned to shit. How fame, booze and drugs turned him into a rock-star arsehole. How he ended up almost a million pounds in debt. And he explains why, in the end, he’s happy to leave all of this behind and move on.

“I’d been thinking about it for a long time,” he says. “And then, a year or two ago, a friend of mine, a retired solider, said to me in an email: ‘You’ve done enough now. You can leave the battlefield.’ And I thought, ‘Yeah, maybe this is the time…’”

When did music first become a major part of your life?

I remember singing along to Hey Jude when I was at primary school, but it was in high school that I really got into music – Emerson Lake & Palmer, Genesis and the Floyd. Progressive rock was my thing. And because I was the sensitive kid who spent most of his time in an attic room listening to records, I got into the words.

Did you write songs back then?

No. I wrote words. I was good at poetry. I loved books. Always got high marks at English.

Could you play an instrument?

No. I was rubbish at music. At school I played the recorder and I couldn’t get a tune from it. When I was 11 I tried guitar. I thought you just picked it up and songs came out. When I realised it needed all this work, I was despondent, in tears. Then my dad bought me an accordion, for fuck’s sake! That’s when I decided I was never going to be a musician.

But you still fancied yourself as a singer?

I did after I saw Rod Stewart and the Faces on telly. Rod was obviously pissed and having a fantastic time. I thought: “That’s something I could do.” So that was my dream, singing along to the mirror in my bedroom.

When did you find the balls to get up on a stage and sing?

I was 21 when I did my first ever gig, at the Golden Lion in Galashiels, singing covers – Steely Dan, Aretha Franklin. That was in 1980. I met up with Diz Minnitt, a bass player. We tried to set up a band up in the Scottish borders. And then, in 1981, we saw an ad in a music paper from a band in Aylesbury that wanted a bassist/singer. The band was Silmarillion. We convinced them to take on a separate bassist and singer, and the rest just fell into place.

Were you apprehensive about moving south, away from home?

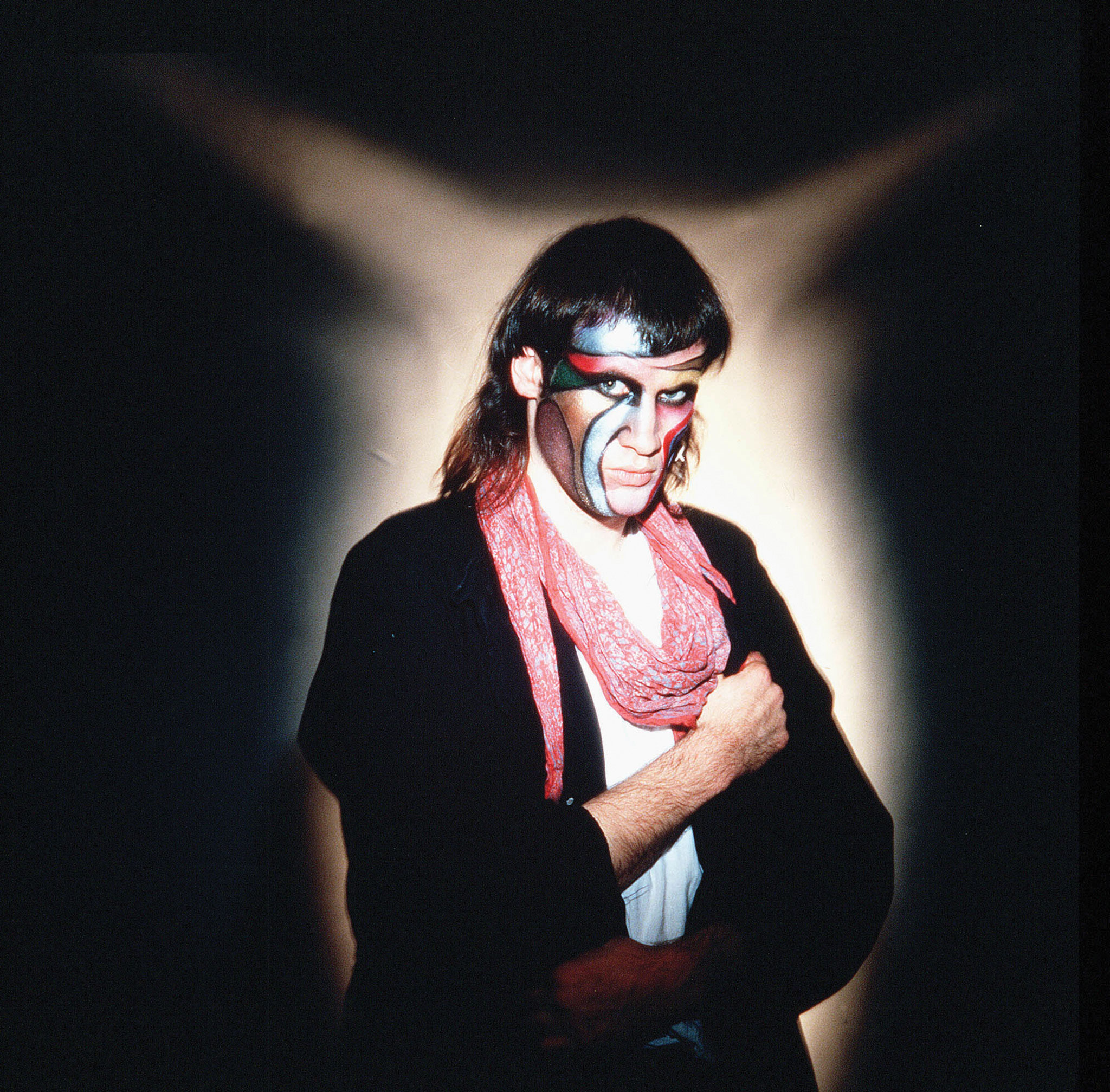

Oh no. It was an opportunity to reinvent myself. In a new place I could be whoever I wanted to be. I’d picked up the name Fish in 1979, and with that name, and the make-up I’d wear on stage, I was able to build up my confidence.

What did the band sound like before you joined?

I thought they were a lot like Camel. It was also very clear to me that Steve Rothery was a brilliant guitarist. And they had no lyricist. So I said, “I have lyrics…” I already had the idea for Script For A Jester’s Tear. I was a big fan of The Who, and when Keith Moon died, I wrote a whole set of lyrics on that theme.

At what point did you realise the band had something special?

I knew it from the first rehearsals. It was an incredible feeling, singing your own words with a bunch of guys who all had a similar taste in music. We were all brought up on those 70s progressive bands, but the Genesis influence was the most powerful – the one in the Venn diagram that brought us all together. We talked music all the time, and there was a great energy between us.

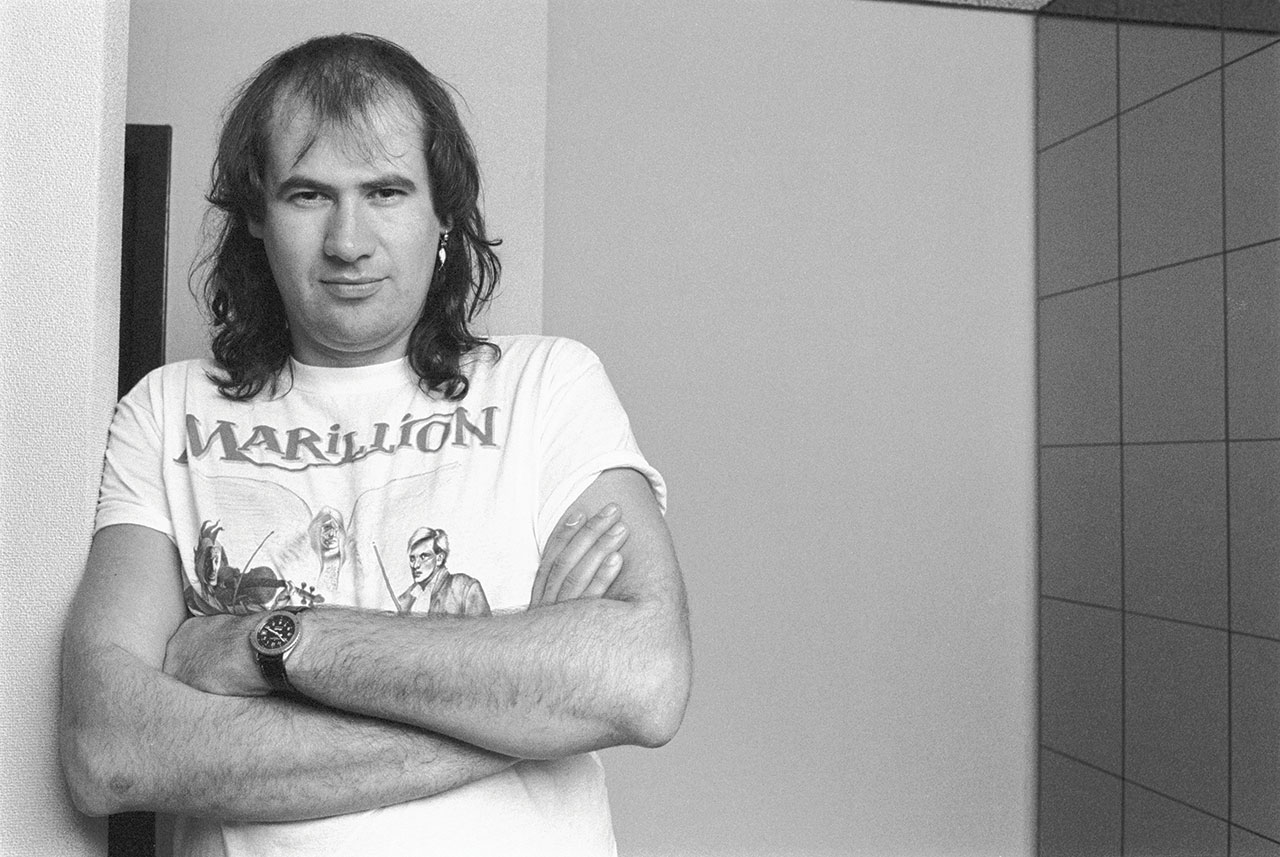

By 1982, much had changed. The band’s name had been shortened to Marillion. There was a revised line-up, with Mark Kelly on keyboards, and Pete Trewavas replacing Diz Minnitt on bass. And with the band signed to EMI, debut single Market Square Heroes was released – featuring, as the B-side, the epic 17-minute track Grendel. Was this your attempt to out-prog Genesis?

Not consciously. We just thought: ‘Let’s write a big, long song, because that’s what progressive rock bands do.’ But yes, it was very, very Genesis-oriented. Basically, it was Supper’s Ready. The music came from a song that Silmarillion had, The Tower. The lyrics were inspired by John Gardner’s book Grendel. Steve and I put the song together and it just swung into that Supper’s Ready thing. It’s funny, many years later I spoke to Tony Smith, the manager of Genesis, and he said that if he’d known about Grendel way back then, he would have sued us!

In your defence, Genesis weren’t writing songs like Supper’s Ready in 1982.

No, they were in Abacab territory by then. They were in pop world.

Did it hurt when critics branded Marillion a poor man’s Genesis?

It used to irritate me at the start. But now, yeah, I can hear it.

What do you hear now in that first Marillion album, Script For A Jester’s Tear?

I hear somebody singing in very bad keys! Sometimes I don’t even recognise the guy who’s singing on that album. That high falsetto voice, it was very forced. But I was young. I didn’t understand anything about music and keys, and I was singing very high. When I think now of singing like that, six nights in a row… fuck that for a game of soldiers.

Bad singing aside, what else do you hear in that album?

I hear the youth, the naivety and the aspiration in it all. Across that album and the next one, Fugazi, you can hear us trying to find our own style. Don’t get me wrong, those are two wonderful albums. But I think Misplaced Childhood was the marker for us, not just because it was a hit, but also because we found ourselves.

The rise of Marillion in the early 80s was part of a bigger story – a prog revival in which bands such as Pallas, IQ and Twelfth Night also emerged.

We never saw it as a revival. We were just doing our own thing. The media at that time thought they had buried progressive rock in ’77. They thought it would never rear its ugly head again. But there were a lot of people out there that wanted to hear that kind of music, and that was the music we wanted to make.

This much was proved with Misplaced Childhood. As a concept album, it was a throwback to the glory days of 70s prog, and yet, in a new era, it was a huge hit.

Yeah! Let’s do a concept album in 1985, when everybody is using synths and drum machines! The truth is, it was a make-or-break album. Fugazi did okay, but we were in danger of being dropped by EMI. We looked at Misplaced Childhood as the last stand. And then we ended up with these hit singles – doing Kayleigh and Lavender on Top Of The Pops.

These were also, for you, deeply personal songs – Kayleigh named, in part, after your former girlfriend Kay.

The whole of that album was an autobiography, in a way. I opened up, and that was when I really found my style as a lyricist. I’d alluded to some personal stuff with the first two albums. Script… was all about Kay, written when we were going through one of our many break-ups. But on Misplaced… I really found the confidence to express myself. That’s why it was a very key album in my career.

Were you concerned that you were revealing too much of your own life in that album?

No. I was happy with that. I think it comes from my Scottish character – a problem shared is a problem halved. That was one of the things in the band that was a bit weird. Everyone else was very English about everything. If people had problems, they didn’t talk about it. Whereas when I had something going wrong, I was quite happy to talk about it. It helped me get through things. Misplaced Childhood was an album I had to write. But it was a double-edged sword.

Meaning what?

I grew as a singer and a frontman. But at the same time, it was when the gang mentality left the band. The filthy lucre came into play.

Was it fun, for a while, being a pop star?

Yeah. We all dealt with that fame in different ways. And being the frontman, I was running point. The press wanted to talk to the singer. My ego got a bit out of control at that time. My hand is up. I was an arsehole. And also, we had bad management. There was a lot of manipulation, Machiavellian shit, between record company and band and management. That’s what led to the lyrics in Clutching At Straws…

It’s a dark album.

It’s actually my favourite album that I did with the band. But yeah, it has a very dark feel. Hotel Hobbies has got a real darkness to it, a beautiful darkness. There’s pathos in Sugar Mice, and also a malevolent anger in songs like White Russian.

On Torch Song on the album, you adopted the alter ego of an alcoholic romanticising about Jack Kerouac. Was this a sign of madness?

The Torch character was a handy tool. You asked if I ever revealed too much. On Clutching At Straws, maybe so. With Sugar Mice and Torch Song, I think I felt I was overexposed. That’s why I invented the Torch character to hide behind. But really, it was just another name for myself.

While you were making that album, was there distance between you and the band?

I just felt alienated. In the studio I was left alone to do my vocals. You want my letter of resignation? It’s in that album. Read the lyrics to That Time Of The Night: it was exactly how I was feeling then.

Some lines in that song are like a cry for help.

That was my state of mind. I was so unhappy with the band and what it had become. On that tour, there was constant arguing. And we were playing huge gigs, but everybody was still struggling to pay mortgages. I felt that our manager wasn’t dealing with our business correctly. He knew I wanted him out. And he told the band: “If I go, you’ll be next.” That’s really what created the crunch scenario: “It’s me or him.”

When the split came, the band were already working on the next album…

Every time I went to the writing sessions, all they had were bits of music; no songs. There was a traditional blackboard – which they still use, by the way – and all the sections were written on it, with arrows where they would join up the sections. I said, “I can’t write over this – I need to have some sort of structure.” Bob Ezrin was supposed to be producing that album. He came to band rehearsals to hear what we’d got, and afterwards he said, “These are not songs.” I was sitting there with a wry smile on my face. And after Bob walked out of the room, the first thing the guys said was, “Let’s try joining this bit to this bit.” I just went, “Fuck this,” and walked out of the room. A week later, I quit.

And you did actually write that letter of resignation.

I’ve still got that letter. I wrote it at my cousin’s house in Gerrards Cross. I was alone there one night. I drank a bottle of Jim Beam and I was still standing. And a little voice went off in the back of my head: “You’re gonna kill yourself.” I realised I was in a very dangerous area. And so, in the morning, I hand-wrote this three-page letter.

Did you cry while writing it?

No – I was angry. I made photocopies and sent them round in a taxi, dropped off at every one of their houses. The next day I get a letter from the manager saying they don’t require my services any more.

What then?

I had to get out of London before the story broke so I went straight up to Berwick to my mum and dad’s place. One night I got pissed with my mates – ironically, in the pub where I’d written Warm Wet Circles [from Clutching At Straws]. The next morning I had a particularly vicious hangover, and my mum brought me a copy of the Scottish Sun newspaper. When I saw the front page it was like one of those things you get in funfairs – your face with a headline like ‘Man Of The Year’ or something. I thought it was a joke, but no. Here was this story about how I was an alcoholic and a drug addict, and that’s why the band wanted rid of me. It made out that I’d been fired. I was fucking fuming.

At the time, it was widely reported that one of the reasons you left the band was because you and keyboardist Mark Kelly hated each other.

Not true. Mark and I are still pretty close friends, and we’ve talked about this on many occasions, after we’ve had a couple of bottles. The whole situation was very complicated. There were a lot of underlying issues – financial stuff. It was never about just Mark and I.

Do you regret how it turned out?

It was sad. And I think if I’d been more business-savvy I’d have stayed on, done the album and tour, and signed a massive publishing deal. But in the end, my sense of honesty and integrity prevailed. I had to get the fuck out of there.

After you left the band, there was a lot of bad blood between you and them.

We got into a very ugly and clichéd public divorce. It wasn’t pleasant. I felt there was a lot of shit thrown about at that time, and stupidly I reacted to it.

Marillion’s album Seasons End – their first with Steve Hogarth on vocals – was released in late 1989, four months ahead of your solo debut Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors.

EMI wanted the Marillion album to come first, so I was on hold. That really pissed me off. What EMI wanted was Phil Collins and Genesis. They knew it would be tough for Marillion to bounce back with a new singer – tougher, allegedly, than it would be for the boy called Fish…

Starting out as a solo artist, did you feel lonely?

I felt lonelier on the Clutching At Straws tour. When I went solo, I had Mickey Simmonds as a foil, a great character. I created a new gang. I also had some great songs for my first album that I’d written for Marillion – songs like Vigil, which they didn’t like, and Big Wedge, which they felt was too anti-American for a band that was trying to break America.

At what point did you cut down on the booze and drugs?

1988, when I left the band. With drugs, there was a conscious clean‑up. I just said, “I don’t need this shit.” But, honestly, the drinking was never a problem.

That’s not what you said earlier.

I was never out of control, swigging a bottle of brandy for breakfast. When the situation with the band got really bad, I wouldn’t say I was hiding in a bottle, but I took my solace in a bottle. Put it this way: when I left the band, the tabloids were offering about 12 grand for a photo of me pissed, and they couldn’t find one. So I never had a problem. I never went to a clinic to dry out.

Why did you decide to go back to Scotland to live?

Up here it was much easier to focus. And I wanted to be as independent as possible. I bought this farmhouse, and in 1991 I had one of the outbuildings converted into a studio. But that year was a killer…

Why was that?

Legal stuff. With the settlement of the Marillion case, and the settlement of the EMI case after I signed to Polydor, the legal bills were something like four hundred grand. That was nearly bullet-in-the-head time. I don’t mean suicide. I mean I was nearly taken out financially.

Added to that, your solo records weren’t hits.

No. Internal Exile, the first album for Polydor, didn’t sell, and with that I lost my self-confidence. I did the covers album, Songs From The Mirror, which was very much the coyote chewing off his foot to get out of the trap. After that, a lot of fans switched off. And the cost of building the studio, another three hundred grand, really put me behind the eight ball.

How bad did it get?

It got to the point where the zeros didn’t matter. In 2001, when my wife left me, I was about nine hundred grand down. A lot of that was interest from the bank. I sold the house and moved into the studio. The financial thing was a guillotine hanging over my head for years and years. But in the middle of all that shite, I managed to pull some great albums out of the hat…

Albums from that period – such as Sunsets On Empire (1997) and Fellini Days (2001) – have now been reissued in deluxe editions.

Yeah. Those albums went missing, but they’ve stood the test of time. I hope now that people might rediscover them.

You also had great reviews for your most recent album, A Feast Of Consequences.

I really enjoyed making that album. The High Wood suite was particularly inspiring and got me into a flow.

And next… Weltschmerz.

I look on this as a very dark album to finish off with. It will have a similar feel to Clutching At Straws.

You’re going to get back on the gear, are you?

[Laughs] No fucking way. Heart attack? No thanks!

So where does the darkness in this album come from?

All you have to do is switch on the news and you think, “Where the fuck are we going?” And that seeps down on a personal level. I have a daughter who’s 25, and my partner has three kids, 19, 18 and 13. Watching their interaction with the world, I’m finding the crystals in which Weltschmerz is born – the state this planet is in; not in a political sense, but in a soulful sense.

As you think about this, your final album, and the final tour to come in two years’ time, do you feel sad at letting go of this part of your life?

No. I’m done. When I was that boy looking into the mirror, the dream was to be a singer in a rock’n’roll band. The current dream is I’d love to write and direct my own movie. And acting, too – I’d like to do more. I’ve done film and TV stuff over the years. The highlight for me was playing a nutter in an asylum in The Jacket [2005]. I did one scene with Kris Kristofferson and Daniel Craig. I got such a kick from that. Who knows what’s in the future? But I won’t be doing action movies – my knees and my back are too fucked.

After all these years, does it still feel strange to think that Marillion was once your band?

No. That was a long time ago. When people talk about reunions, it’s kind of disrespectful, because Steve Hogarth has been in that band for a lot longer than I was.

Have you and him ever talked about that?

Yeah. He and I are fine. The thing we both have to deal with is the fact that the biggest albums the band made were the first four. They’ve never had – and I’ve never had – the success that we attained up to ’88.

And the most famous of those albums, Misplaced Childhood, is now consigned to your history. The Farewell To Childhood tour must have been emotional.

There were moments when I had a lump in my throat: moments when I was singing about Kay, and about Mylo – our friend John Mylett, the drummer from Rage, who died so young. When Kayleigh was a hit, the Daily Mirror had this story: who is the girl behind the song? And I swore to Kay that I would never tell. But in 2006, she and I got back in contact. She told me then that she had cancer. And in the last year of her life, she told everyone that she was the girl in the song and that Fish was her boyfriend. So yeah, there were times on that tour when the emotions were so high, you couldn’t help but cry.

Will there be more tears in 2018, when you take your final bow?

I don’t really know how I’ll feel. But I doubt there’ll be dry eyes at the end.

Fish’s remastered solo albums are out now – see Fish’s website for more information.

Marillion confirm 18th album F.E.A.R will land on September 9