Ian Anderson interview: the beginning, middle and end of Jethro Tull

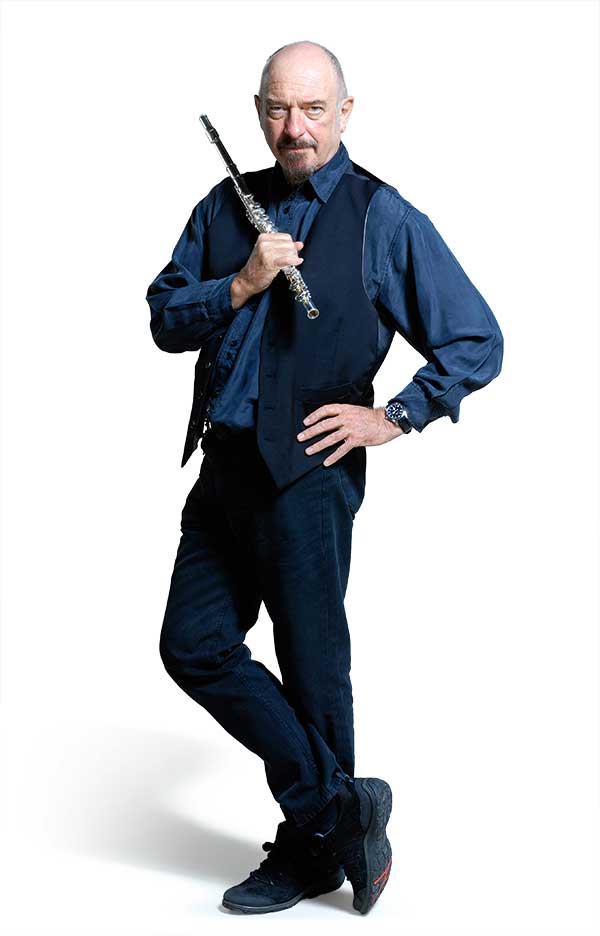

Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson might have become an average blues guitarist. Instead he became the best one-legged flute player in the world, and for more than 50 years led his band to critical acclaim and huge commercial success

There’s an awkward moment when Ian Anderson arrives in Bath for the Classic Rock Interview. As he emerges from the train station on a rainy winter morning, dressed for the weather in an anorak and woolly hat, he recoils sharply when I offer a handshake.

“I don’t mean to be rude,” he says. “But I’ve got a bad wrist.” With a thin smile, he adds: “I’m probably a close second to Pope Francis for getting upset with people grabbing my hand without asking first.”

He has a bad leg, too. And as bad luck would have it, it’s his right leg, the one on which he has always stood, with his left peg dangling, while playing flute as frontman for Jethro Tull, the band he has led since 1967.

“Quite painful,” he says of the torn meniscus in the knee joint.

This injury, like that to his right wrist, is result of the occupational hazards common to many stage performers. Anderson sprained his wrist in a fall during a show in 2019.

“The problem with my leg goes back a long way,” he explains. “I damaged both knees in the seventies because I was stomping around on stages and impacting the joints. But my knees were in worse shape twenty years ago,” he says with a shrug, “so I suppose I should look on the bright side."

Early in our lengthy conversation in the bar of the Francis Hotel, it becomes apparent that small talk does not come naturally to Anderson. Instead, he launches into a detailed analysis of the policy mistakes that cost the Labour Party the recent general election, before stating his support for the Liberal Democrats.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

As he will say, he is not the archetypal rock musician.

Ian Scott Anderson was born in Dunfermline, Scotland on August 10, 1947. He was a teenager living in Blackpool when he joined his first group, The Blades, in 1963. As a singer, guitarist and harmonica player, he served his apprenticeship in various blues bands before Jethro Tull – named after the 18th-century agriculturist – formed in 1967, the same year in which Anderson took up the flute, on a whim.

In the 70s, Tull’s idiosyncratic blend of progressive rock, hard rock and folk music made them one of the biggest bands in the world via a series of landmark albums including Aqualung, Thick As A Brick, Minstrel In The Gallery and Songs From The Wood. And while many musicians have passed through the line-up during the band’s long history, at the age of 72 Anderson remains captain of the ship.

That history is celebrated in a new and beautiful silk-bound book, The Ballad of Jethro Tull. And while Anderson continues to tour and record as a solo artist, he and his current four-piece band had planned to tour throughout 2020 with what he calls “a big production show”, Jethro Tull: The Prog Years.

“I perform under the name Jethro Tull depending on the kind of concert it is,” he explains. An expansive talker, witty raconteur and deep thinker, he relates the band’s story, and his own, over two hours, fuelled first by coffee and later, after midday, a large Scotch. He begins with an early memory, of a small boy living in Scotland, who found something in music that would shape the rest of his life…

As a young boy living in Dunfermline in the early fifties, what was the music that first had a powerful effect on you?

I was sent to Sunday school, so the first music ever heard was church music, and little snippets of Scottish folk music. Then, when I was about eight years old, I heard big-band jazz, and after that the early Elvis – Heartbreak Hotel, Jailhouse Rock – when Elvis was dangerous, before he got sequinned.

Did you go willingly to Sunday school?

No. I was terrified of churches. I didn’t understand what was going on. I questioned religion and I was angry about it. I had a real aversion to the dogma of the Christian religion I was brought up with – scaring people into the arms of Jesus as opposed to the prongs of the devil’s pitchfork.

When you were twelve your family moved to England, to a bigger town, Blackpool, where you spent all of your teenage years. What are your clearest memories of that time?

When I was around sixteen I became aware of this thing called the folk revival. That was when I first heard Bob Dylan, and I didn’t really take to him at all. But at the same time, I heard Muddy Waters, which got me into blues, particularly acoustic country blues, and that would become my route into the professional music world.

Growing up in Blackpool, drinking and fighting and drugs were all very much part of my teenage awareness of what was around me. But when I was seventeen, someone bought me a half of lager, I hadn’t had anything to eat, and I went out into the street and threw it up. I didn’t drink again until I was twenty-five, on tour with Tull in America.

And drugs?

Of course, I knew about that stuff. I’d see people popping pills at the Twisted Wheel in Manchester. When I went to art school, in Blackpool, some of the guys were smoking marijuana. I had a friend in life-drawing class who had marks on his arms. I thought it was a rash. He said: ‘No, it’s needle marks. Heroin.’ But it was never seductive to me. I always saw it as something of a personal threat. I don’t like anything that changes my perception or my chilling, lizard-like mental capacity.

Blues was what you played in your first band, The Blades, and so it continued when the first line-up of Jethro Tull came together in 1967.

We came out of that period where to get a gig – let alone get a record deal – you had to be in a blues band or an out-and-out pop group. But on the periphery there was Captain Beefheart and the Graham Bond Organization – very different to purist black American blues – which was important to the development of Jethro Tull.

And that signpost got bigger in the summer of sixty-seven when Pink Floyd had The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn and The Beatles had Sgt. Pepper. Those records energised me – you could step outside the comfort zone of twelve-bar blues or pop music and you could do something different.

It was also in that summer of ’67 that you first picked up a flute.

I’d been playing guitar and harmonica, but as a guitarist I was never going to be as good as Eric Clapton, simple as that. So I parted company with my Fender Strat, whose previous owner was Lemmy Kilmister, who was then the rhythm guitar player for the Rockin’ Vickers, and I bought a flute, for no good reason. It just looked nice and shiny.

Was the flute easy to master?

At first I couldn’t get a note out of it. I put it back in its case and never touched it again for six months, until somebody said to me: “You don’t blow into the hole, you blow across it.” Oh, okay. Suddenly I got a note, then another and another. Within a week I was playing blues solos and it became part of our gig. That was the beginning of the Jethro Tull with the guy who stands in the middle playing the flute while standing on one leg.

Always the same leg?

Yes. Ever since I started playing harmonica at the Marquee club I’ve always stood on the right leg.

Although you were inspired by the psychedelic sounds of The Beatles and Floyd, on the first Tull album, This Was, released in October 1968, blues was the dominant tone.

Yes. Mick Abrahams, the guitar player, loved blues and R&B. And as he was a little older than the rest of us, he was the guy who knew what he wanted to do. But when I started writing on guitar for the second album, my stuff didn’t really gel with Mick. So it was a very important moment when Mick left the band and Martin Barre joined in January of sixty-nine. Straight off, Martin understood what I was getting at.

Which was what, exactly?

It was a more eclectic thing, bringing in elements of Western classical music, Asian music and even church music – the beginnings of something that was a little more spiritual. And also some real hard, driving rock songs. All of this stuff was in my head, but it required the input of Martin Barre, particularly.

He was a very unfinished, unformed guitar player, so he and I were fumbling together, and that fumbling was what helped him develop a style and helped me develop as a songwriter.

With that second album, 1969’s Stand Up, did you feel that Tull had defined their sound?

Stand Up was the first really important album. It was the one where it was now a band that wasn’t the same as everybody else. It was becoming something much more individualistic. We’d left the blues behind. That album was melodically and rhythmically more adventurous.

It wasn’t what I would call progressive rock, because some of it was definitely not rock music. But it was around that time that the term ‘progressive rock’ first appeared in the UK music press to describe Yes, King Crimson and Jethro Tull, among others. And then a little later there was Emerson, Lake & Palmer and the early Genesis, by which time prog was up its own arse, obviously.

Do you mean ELP and Genesis specifically?

I was never a fan of Genesis, but their musicianship was incredible. And ELP were complete show-offs. But Greg Lake, who I never liked in the old days, became someone I was very close to in the years before he died.

For someone synonymous with progressive rock, you seem a little dismissive of it.

I just look upon it with a benign smiley face, a bit like Rick Wakeman does. You need a sense of humour about these things. ELP, when I got to know them, seemed to be capable of laughing at themselves. The caped Rick Wakeman is absolutely an arch villain of prog excess, musically and in terms of general appearance. He knows it’s a bit of fun. To some people, Jethro Tull is a prog band. To others it’s a folk rock band or even a hard rock band.

And to you?

It’s a lot of little delicate shifts from one thing to another. With Jethro Tull you can’t wrap it up in the way you can wrap up Status Quo.

Your love of folk music, rooted in your childhood, had a strong influence on many early Tull albums, and over the years you’ve worked with a number of folk artists: Steeleye Span, Fairport Convention, Roy Harper…

In the seventies, Tull were close with Roy Harper, as were Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd. I liked Roy because he was a nutcase whose whole stage persona was based on being completely out of it, even though he was only stoned about eighty per cent of the time.

Roy was a great man with ideas and lyrics that were off the beaten track. He would sing very delicate and touching love songs, and also brave stuff like I Hate The White Man. That gave me the confidence to try to let out those kinds of emotions in my own music.

Aqualung, Tull’s the fourth album, released in 1971, became the biggest seller of the band’s career, and a rock classic.

Aqualung is an album of contrasts. It had some big, bombastic rock songs – Locomotive Breath and Aqualung – but also the singer-songwriter thing. With some of the songs, I was in the studio on my own, playing acoustic guitar. It wasn’t that it was folk music, but it was acoustic music, which the band would to some degree add other components to.

That album wasn’t a huge hit out of the box. It did okay at the time, a bit better than the previous ones, but it just kept on selling over a long period of time. The last time I looked, a few years ago, it had clocked up twelve million sales. Pretty big.

And also your masterpiece?

Certainly there are songs on that album that I’m pleased to have in the repertoire, Aqualung and My God and some of the acoustic things that are a little more whimsical and personal. The only rubbish thing about that album was the bloody awful painting on the cover, which I never liked.

Why?

The character on the cover is a homeless person. My first wife, when she was studying photography, had photographed some homeless people, and that was the source of the song Aqualung.

Many of the songs I’ve written over the years have come from either a photograph or a memory. I think in terms of visual imagery, something I share with many British musicians who went to art college.

That’s how Aqualung developed, as a series of little visual images that I made into songs. But when the artist, Burton Silverman, delivered this painting for the album cover, based, I think, on a photograph he took of a homeless man in the Strand…

It looked a lot like you.

I’d been really emphatic about it: I’m not this character. I’m not a homeless person. I’m a spotty middle-class English kid. I’ve never had to sleep rough on the street, and I don’t want to be pretending to be that character. But our manager, Terry Ellis, had obviously had a quiet word with Silverman: “Make it look like Ian, we’ll sell more records.”

So the character on the cover looks like a cross between me and John Lydon when he was Johnny Rotten. That might explain why John Lydon later said that Aqualung is one of his favourite records. Which certainly was not in keeping with Malcolm McLaren’s instructions.

The next album, Thick As A Brick, was another of the band’s best. After Aqualung was misconstrued as a concept album, you created Thick As A Brick as a spoof concept album.

Well, yes. I was absolutely truthful about Aqualung not being designed in any way as a concept album. It had three or four songs that kind of hung together. The rest of the songs had nothing to do with each other in terms of musical style or lyrical content. So with Thick As A Brick I thought: “This is going to be a bit of parody of what was then becoming ‘the prog rock thing’. I’ll have a little dig at it, a bit of a spoof.”

And yet for all the humour in Thick As A Brick, there was a deeper meaning in your portrayal of fictional boy genius Gerald Bostock.

It was kind of serious stuff, yes. It was all about my childhood, growing up in the fifties in that era of the postwar Biggles hero mentality. Not the passage of boy to man, it was the passage of child to adolescent. That album was about all the misconceptions that came out of the way we, as children, get brainwashed

Brainwashed in what way?

Back then there were these comics, Rover and Lion, which had stories about ‘Jerry’ and ‘The Hun’, sending out these awful nationalistic stereotypes, which hopefully most of us kids didn’t take too seriously. But I remember the first time I went to Germany in sixty-nine, on tour, and in my head I could picture Sergeant Braddock shooting down the Hun!

All of that stuff was part of my childhood, and it took a while to readjust to the fact that you were now in the postwar ruins of Berlin, it was a new era, the Cold War, and things were different to what you were brought up to believe in – the idea of this rather defiant and very nationalistic British sentiment.

The cover of Thick As A Brick was brilliant, designed as a send-up of a provincial British newspaper, which you named The St. Cleve Chronicle And Linwell Advertiser. Presumably you were happier with this one?

I was responsible for instigating that cover. Terry Ellis hated it. “You can’t do this, it’s ridiculous!” I said: “Trust me, it’s going to work, it’s going to be good.” It was that very British surrealistic humour that began with The Goons and continued with Monty Python. It was weird, but we all got it. And then the Australians got it. And finally even the Americans got it!

Did that surprise you?

Well, when Monty Python And The Holy Grail came out [in 1975], I was one of the backers of the movie. When I saw it with the band, in New York, we were in hoots of laughter in certain bits, while the rest of the audience sat in complete stony silence. And then they all laughed at bits where we thought: “That’s not funny, that’s too corny and obvious.” It took a while for the Americans to catch up with Python and with Thick As A Brick, but they did.

It sounds like you had a lot of fun with that album cover.

Oh, we had a barrel of laughs doing it. We stole that Pythonesque approach, making up all of these completely ridiculous and fictitious things. It was all very silly and schoolboyish and, as you say, a lot of fun.

And just recently, when I was having lunch in Heddon Street in London, I walked past the bank where we did some of the photos for that cover – when Jeffrey [Hammond, bassist] had to run out wearing a mask and carrying a briefcase as if he’d robbed the bank. During that shoot the police were called. Some people thought that Jeffrey really was a bank robber. And when a policeman turned up, we didn’t think he was a real policeman. We thought it was one of our lot dressed up! It was all very confusing.

In 1976, a year before the Big Bang of punk rock, the knowing title of Tull’s ninth album – Too Old To Rock ‘N’ Roll: Too Young To Die! – seemed to anticipate the coming storm.

It was throwing down the gauntlet, for sure. Same as in the opening lines of Thick As A Brick: ‘I really don’t mind if you sit this one out.’ It was confrontational. Too Old To Rock ‘N’ Roll: Too Young To Die! is a red rag to a journalistic bull if they want to come after you. But it’s better to have some level of self-deprecating humour.

Were you thinking, even then, how you might grow old gracefully in this business?

I thought it was enough that as a musician I might just grow old, whether gracefully or disgracefully. Rule number one is: try not to die when you’re twenty-seven. Rule number two: try not to die when you’re in your fifties through the rock’n’roll lifestyle. You know, don’t cross a busy road unless you really have to.

The only rubbish thing about Aqualung was the bloody awful painting on the cover, which I never liked

Ian Anderson

There was prescience, too, in Tull’s 1979 album Stormwatch, with the song North Sea Oil warning of the environmental crisis to come.

That wasn’t a prophecy. I can’t claim in any way to be way ahead of my time. That’s far too generous. I was simply reacting to things that were being discussed in certain circles. When the first elements of climate change were being identified back in the early seventies, you didn’t have to be a university professor to know that stuff. The information was out there in the public domain if you cared to look for it.

Stormwatch was also the last album made by what is widely considered to be the classic line-up of Jethro Tull: you, Martin Barre, keyboard player John Evan, drummer Barriemore Barlow, bassist John Glascock and keyboard player and orchestral arranger David Palmer. In November 1979, just two months after it was released, John Glascock died at the age of twenty-eight as a result of a congenital heart condition. It was said that he’d damaged his health with drink and drugs, and that you’d threatened to kick him out of the band in an effort to straighten him out. What’s the truth in that?

John was always a bit of a party guy from the get-go. He wasn’t a wildman. He was an easygoing, nice guy, a benign drunk. And I’ve known people who were not that way. John was never fired from the band. He was just told by me: “You’ve got to stop and get yourself fixed, and come back when you’re well.” When we stepped away from day-today contact with him it could have gone either way. I hope he knew his job was waiting for him if he could make it back. But he didn’t, and that was the great sadness that we had.

How did that affect you emotionally?

It made me angry with him. It made me angry with myself. I could have done more to confront John and steer him back. We all could have tried harder to make him understand that this really wasn’t a great way of living his life, and his job depended on sorting himself out. But one will never know if his demise was due to the failure of the heart surgery he had, or to what degree it might have been aggravated by his lifestyle.

Within a year of John’s death, Barriemore Barlow and David Palmer had left the band. These were old friends of yours. Before Tull, Barlow had played alongside you in The Blades in the early sixties, and Palmer had worked with Tull since 1968. And in all those years, Palmer had kept a secret from you, a secret that was finally revealed in 1998, when Palmer came out as transgender, renaming herself Dee.

I remember it well. I called him – and I’ll say ‘him’, because at that point, as far as I knew, he was David Palmer – to say: “I’ve got a bit of a problem here with some journalists hanging around my house insisting that I’m cross-dressing and that I’m planning to have a sex change.” I laughed it off and said: “Where could they have got this story from?” At which point David said: “Ah, Ian, I’m glad you called…” And I quote him quite precisely here: “There’s something I’ve been wanting to get off my increasingly ample chest…”

Do you think there were clues that you’d missed?

There were some signs. The clothes that David was wearing in the late seventies seemed a little odd, a little ambiguous. Somebody had said: “It looks like there’s a bra strap under his shirt.” But in all those years, he and I never had a conversation about the issues he had as a child, growing up in an uncomfortable way.

That conversation came much later on, after the gender reassignment – a complete transformation. When I saw her then, it was quite difficult for both of us. It was difficult for a lot of people who knew the old David Palmer, because he had seemed in many ways like the last person in the world who would go in that direction. He was kind of a man’s man. He smoked a pipe and spoke with a deep voice. David was in his sixties when he made his decision. It was a very brave thing to do.

Dee Palmer is one of many former members of the band interviewed for the book The Ballad Of Jethro Tull. But one key figure from Tull’s glory days didn’t contribute to it.

I managed to persuade a number – sadly not all – of ex-band members to contribute their memories and thoughts. We picked the main guys who played with the band for a number of years – John Evan, Jeffrey Hammond, Dave Pegg, Doane Perry. But Martin Barre declined to partake of the opportunity to help sell a book, make some money and publicise his own efforts. He felt for whatever reasons he had that he didn’t want to do that.

It was very interesting for me to read what all these people came up with. They remembered things differently to me, which gave another insight into the period where we spent a lot of time together. I didn’t edit anything from their contributions, and I think they were very diplomatic, actually.

There’s a bit of bad blood between some ex-band members. Not with me, but with each other. They have to be nice to me because they still get their royalties twice a year [laughs].

In putting the book together, was all that digging into the past an emotional experience for you?

Not really, because the visitation of all of that is what I do for a living anyway, through the music. I’m always going back through the old catalogue, with a view to different songs being in the set-list. And as I said from the start, this is not a tell-it-all, sex, drugs and rock’n’roll book, because we weren’t that kind of a band.

What kind of band was it?

It was a ‘go to bed early and read an Agatha Christie book’ band. But there’s always a party guy in every band, and in the early days, before John Glascock, that guy was Glen Cornick [bassist from 1967 to 1970]. When Glen discovered America, and America discovered him, they embraced in a not always healthy way. He’d be out drinking and clubbing, which put a bit of a wedge between him and the rest of us. Glen was lovely guy. He just wanted to make every minute count when he became famous.

You said it was when Tull toured America in the seventies that you started drinking.

I would have a beer, Lowenbrau, this awful, sickly German beer that was on our rider. But I wouldn’t drink socially, only in the privacy of my dressing room. Or sometimes after a show we would have a drink in a hotel bar, but it was one drink.

In those days the band were so tight musically. Were you tight as people as well?

Within any group there will always be one or two who chum up. In the early days nobody wanted to chum up with Glen Cornick, but I ended up rooming with him. It wasn’t great. I, like Martin Barre, preferred my own company.

Have you changed at all in that respect?

No. I’m a loner. When you’re touring, you’re a part of a social group, intensely, from sound-check to getting back to the hotel. But I travel alone. I use public transport and book my own trains. And I eat alone. I can’t abide sitting down to eat with other people if I can avoid it.

You still spend a lot of time on the road, with Tull tours and also doing your more intimate solo shows.

It’s an interesting format for the solo shows, a bit of music and then Q and A, where we invite the audience to become Andrew Neil and try to pin me down and see what a slippery character I am. We did a couple of tours in America called Rubbing Elbows With Ian Anderson.

It’s a lot of fun, and you do get a few quite wacky questions from the audience. One woman asked me: “Does standing on one leg mean that one leg is stronger than the other?” I stood up said: “Does one look bigger than the other to you?” She said: “Yeah, your right leg looks a little bigger.” I said: “That’s an astute observation. But unless you have a tape measure with you…” And of course she put her hand in her pocket and produced a tape measure. So she ended up on stage, measuring my thighs.

Do you still enjoy travelling the world?

Always. I have a great love of Americana, but for me, Europe, with its many languages and cultures, and even the different spins of Christianity, it’s very fascinating to this day. I always felt very connected to Europe from the early seventies onwards, and that, I think, reinforced my musical inclinations.

I still play things by Muddy Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson, just to remind myself of where my voyage began as an aspiring professional musician, but really it’s the European stuff that always got to me – all great composers, German, Italian and Austrian.

So I am instinctively a remainer, maybe not entirely in the political sense but in the cultural sense. I love Europe. I’m not a huge fan of Italian food but I can’t wait to dip into my spaghetti vongole again. It’s like meeting an old friend. But eating alone, of course. And hopefully in a deserted restaurant.

You also perform fundraising shows in various cathedrals and churches across Europe and the UK. That’s quite a turnaround for someone who was terrified of churches as a child.

I like the idea that we should be doing what we can to preserve certain institutions and traditions, even if we are not necessarily, as individuals, people of faith. I can’t call myself a Christian, but I have a huge cultural attachment to Christianity. It’s what I grew up with. I have a huge reverence for churches and cathedrals, and when I perform in these places I try to find that difficult balance between the music of the church and the music that I do.

It gets a bit edgy at times, where some of my music pushes the boundaries in terms of lyrical content, but nobody walks out. The audience understands. We’re not trying to evangelise you, we’re just trying to take your money to fix the church roof. Sometimes when I meet new people and they ask me what I do, I say I work for the Church of England. It’s easier to explain than saying I play flute in a rock band, because lots of people, especially younger people, have no idea about Jethro Tull.

Some of your most powerful songs have addressed religion, most notably My God, from Aqualung.

My God was the one that got people’s knickers in a twist in the Bible Belt of the USA, mostly from worshippers who got the wrong message. But even back then, and certainly now, there are priests who say to me: “I know what you were talking about with that song.”

In the seventies, some of our songs, the ones about religion, were banned in Spain and Italy. People thought we were treading on toes. But now, in Italy My God is the most famous Jethro Tull song.

So where do you stand with all of this now?

I do not have faith. I believe in possibilities. I believe in probabilities. I have no time for certainties. Certainties are too close to delusion. I believe in Jesus of Nazareth as a slightly radical, bolshy Jewish prophet. I do not believe in Jesus the Christ. I believe in the wonderful story of The Bible, the ethics in the teachings, but I can’t offer myself as having faith. Agnosticism – on a scale of one to ten, you can put me down as about a six and a half. I’m edging towards ‘There could be something in all of this’, but I’m not pushing myself to resolve it any time soon.

Ask me again on my deathbed and I might be calling for the priest. But right now I’m okay. I’ve got a wobbly knee but I’m all right. And really, the idea of faith versus no faith at all is a bit like Boris Johnson’s very right-wing Conservative party versus Corbyn’s very left Labour party. It’s a sharp division, and I’m a person who instinctively occupies more middle ground in most areas of life. Which doesn’t make me a very good model for the archetypal rock musician.

You say that, but you’ve had the kind of career that most musicians can only dream of. You’ve enjoyed huge success on your own terms. And in 2008 you were awarded an MBE for services to music. What does that mean to you?

In an entirely non-disparaging way, I refer to it with affection and respect as ‘the village postman award’, in the sense that lots of people who are awarded MBEs are unsung heroes of everyday life. With the honours system, the higher up you go, the more likely you are to be cynical about those who are knighted, because it usually involves a lot of dosh. But the lowly MBE does represent great members of society, so I’m perfectly happy with the idea of being honoured for ‘services to music’.

Another award you, with Tull, received, in 1989, was aGrammy for Best Hard Rock/ Metal Performance. It was a shock result, Tull winning in a category in which that year Metallica were the overwhelming favourites. When that happened, were you as amused and perplexed as everybody else?

I didn’t think it was very likely that we would win the Grammy, and yes I was a little perplexed and amused when we were nominated in that category. Our record company told us: “Don’t bother coming to the Grammys. Metallica will win it for sure.”

My view is that we weren’t given the Grammy for being the best hard rock or metal act, we were given it for being a bunch of nice guys who’d never won a Grammy before. And there wasn’t an award for the world’s best one-legged flute player, otherwise I’d have to buy several more fireplaces to have enough mantelpiece space for all the trophies.

So what does the future hold for the world’s best one-legged flute player? Is there more music in you?

I’ve been recording, but I’m yet to finish the album.

A solo album, not a Tull album?

I’m not telling. And I always like to reserve the right to change my mind.

Come on, Ian…

There’s really not much to tell. Yes, it’s a concept album. It’s not a bunch of love songs. It’s songs that are thematically joined at the hip. But the connection, I want people to figure that out for themselves. I like a bit of mystery.

At this late stage of your career, is there any chance that you would get what’s left of the old band back together for one last hurrah?

It would be an awfully crowded stage. And in many cases those old band members no longer play and haven’t for many years. It’s a tricky one. And I’ve always felt awkward about the idea of getting the old band back together, because which edition of the band are we talking about? Picking some people and not others would be favouritism. And I don’t have favourites.

As you say, Tull lives on, and will do for as long as you’re out there playing the band’s music.

If the show is all Jethro Tull repertoire, I feel that’s Jethro Tull. If you looked at Wikipedia two or three years ago, it said ‘Jethro Tull was…’ Now, that past tense has disappeared, due to some grudging acknowledgment that Jethro Tull goes on. I’ve always argued that Jethro Tull is not at an end any more than The Beatles are. The Beatles still sell millions of records and downloads. The glorious thing about the world of entertainment is that your work lives on after you.

And when all is said and done, are you happy with your lot? Has life been good to you?

I’ve felt like that for a long time. I jokingly say, but there’s a lot of truth in it, that one of my favourite hobbies is waking up in the morning. I like to wake up in the morning every twenty-four hours! It’s a great pursuit to follow. And the first thing I feel when I wake up is a feeling of gratitude.

Jethro Tull: The Prog Years Tour kicks off in Aylesbury on September 30. The Ballad Of Jethro Tull can be ordered now.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”