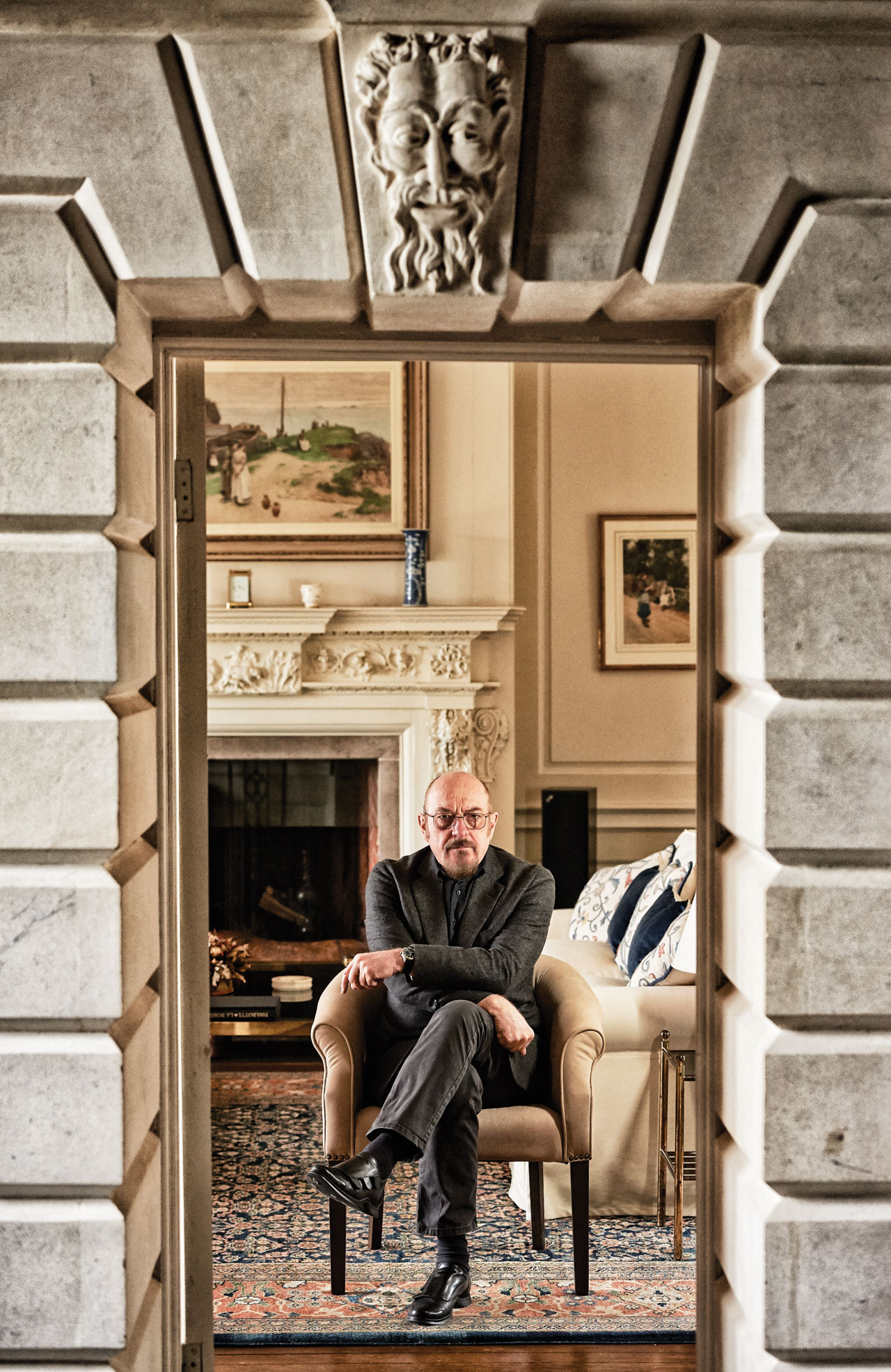

It’s Sunday. For many of us, it’s a day apart from the usual hurly‑burly of the week; a day to take a walk, spend time with family and friends, read the papers or watch the match. Not for Ian Anderson. For him, the traditional day of rest is more often than not spent behind the desk in his office.

“I sit there and do itineraries and make plans. I plan things in a way that, generally speaking, everyone knows what’s going on. Right now the itinerary goes all the way through to the end of the year and is available for band and crew to peruse so they can see the way things are shaping up. In most cases the flights are there, and even though I may not have booked them yet, I know what airline, what time a flight we’re going to be on, the venues and the local production people. It’s all there.”

He speaks with a degree of pride in his voice. “Other people are sitting planning their summer vacation and I’m there doing something not too dissimilar, in the sense that I’m also planning trips.”

Approaching his 70th year on the planet, Anderson has no desire to slow down. While he’s happy to admit to putting his feet up and immersing himself in a good book, you get the feeling he’s at his happiest when he’s busy at the creative coal face. “Generally speaking, I like to be doing something that most people would call ‘work’ every day because it feels rewarding.”

He recently completed the production of a new release, Jethro Tull – The String Quartets, describing it as being “essentially well-known Jethro Tull pieces done in a fairly authentic classical string quartet context, but carefully arrived at so as not to drive people to eBay”.

At Christmas he signed off on Songs From The Wood, the next instalment in the series of Steven Wilson surround sound and stereo remix albums, set for release later this year. And then there’s the ongoing work on a new album.

At a time when the importance and the relative significance of a new album has been displaced from what was once its pre-eminent position in popular culture, news that Anderson has another collection of new material in the pipeline is nevertheless welcome. While reworking classic material into string quartets, rock operas and issuing remixes might well constitute useful elements when it comes to maintaining a certain band as brand profile, the one real measure of a functioning artist is the extent to which they have something new to say about the world as they see and experience it.

“Right now I’m working on some lyrics and have one more piece of music to write. I’ll then be making demos of the first six of these pieces that we will be rehearsing and recording with the band in early February. Then the rest of it will get recorded piecemeal in the gaps between concerts and so on, and that will be scheduled for release in early 2018.”

That year has a special significance for Anderson. Not only does it see a new album but it is, he says, the 50th anniversary of Jethro Tull. When Prog suggests that the end of 1967 was when Glenn Cornick, Clive Bunker, Mick Abrahams and himself got together and therefore it’s ’67 and not ’68 as the anniversary point, he’s having none of it. In a tone reminiscent of a patient headmaster addressing a well-meaning but wayward pupil, he sighs.

“The band Jethro Tull didn’t start in ’67. We became Jethro Tull at the end of January 1968. Although the first four members of the band, including me, did get together at the end of 1967 in December, or maybe late November, it wasn’t called Jethro Tull at that point. We had a number of names before then. So technically 1967 is not the anniversary year. You’ll have to wait until early 2018 for that.”

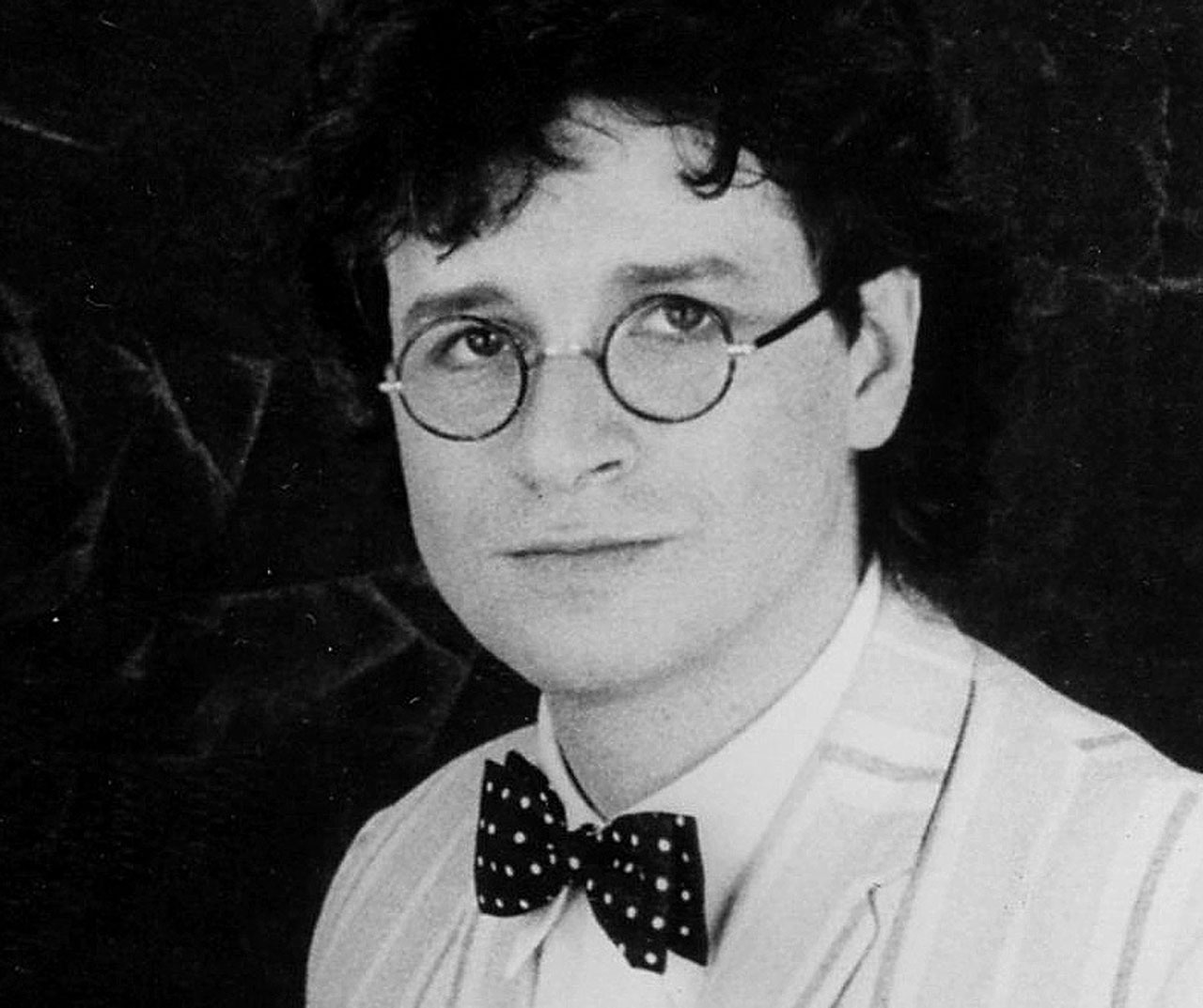

What isn’t in dispute is that Anderson and company recorded This Was not long before his 21st birthday. These days we think nothing of musicians performing and recording at what would be regarded as retirement age. Back then, as they made their debut album, he gave no thought to questions of such longevity.

“I suppose the thought in my head back then was that if I was lucky enough to maybe make a record then that would be a huge achievement. I could then go back to art college and finish my education and become an art teacher or something. Maybe I thought I’d stay somehow on the periphery of the music business, as an agent or working with a record company or as a producer – something like that seemed possible. But as a performing, active musician, I don’t think I was brave enough to think it would last more than two or three years.

“Later I changed my outlook because I reminded myself of the fact that most of my musical heroes, when I was growing up as a teenager, were not young lads: they were all venerable jazz and blues musicians, and of course classical and folk musicians. Then I began to rethink: ‘Well, all these other folks have long, workable careers and they left behind them a huge repertoire and a huge legacy of music.’ I dared to think, for the first time, that maybe I could still be a musician at the age of what I suppose we thought of as retirement age. But then that means they have to cart you off the stage with your boots on…”

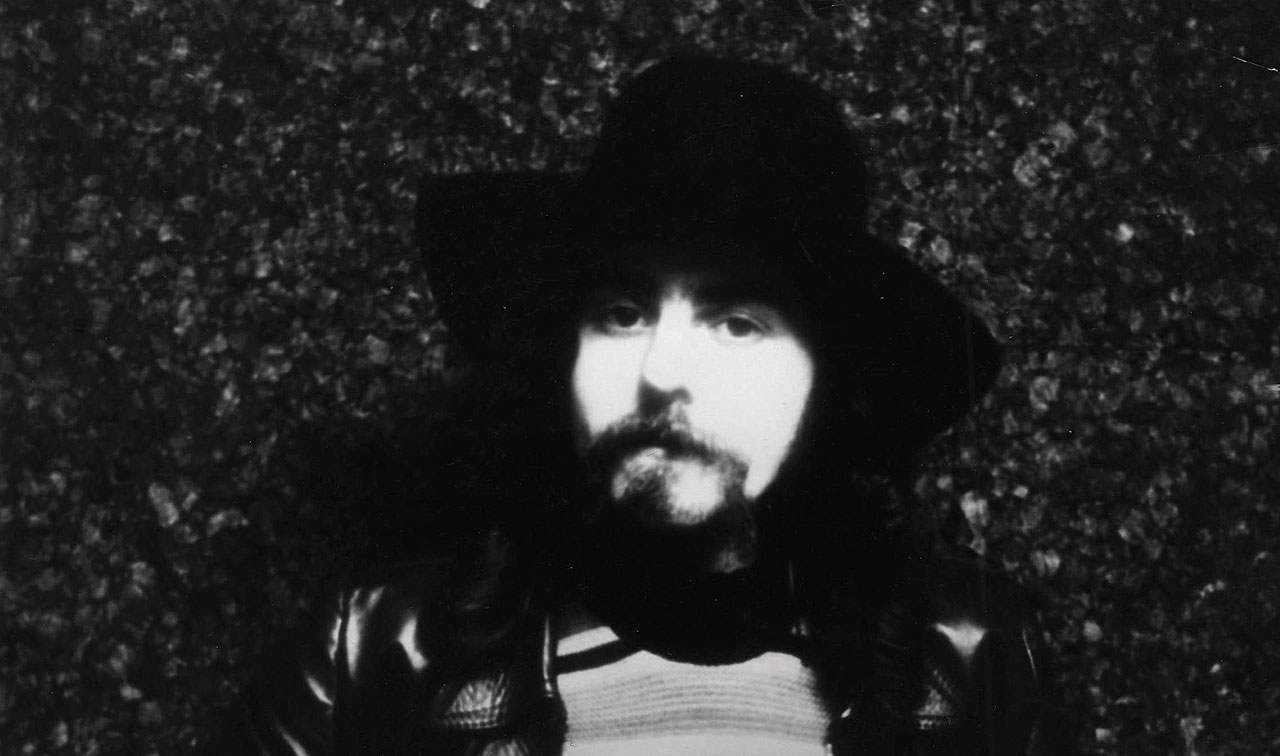

On stage, Anderson has always cut a dramatic, hugely energetic figure. Flute in hand, with his improbably long hair flailing about him, he strutted and darted about the boards, his long coat billowing like the cape of a superhero. The overcoat, colloquially known as a dead man’s coat, a utilitarian item of clothing discarded by an older generation, was appropriated by youth culture. It become a wearable freak‑flag of sorts, marking the wearer as a member of the underground scene – at least on weekends and at Jethro Tull concerts. How many fans emulating their hero hoped a bit of that wild, slightly dangerous energy might rub off on them?

Looking at Tull in general and Anderson in particular, one imagined life on the road after the shows to be an endless parade of Caligula-like debauchery. Not a bit of it, says Anderson. “This would probably apply to Martin Barre as well, but we were rather private people who tended not to go out with either hangers-on or friends. We didn’t go clubbing. We weren’t big drinkers. At least half the band, even in the early days, were naturally just rather quiet people. I know Martin and I both read a lot. We’d be quite content on a day off to sit in our hotel room, read a book, go for a walk, pick up a sandwich somewhere and try and just walk around the town, without any fuss and bother.

“Drugs didn’t feature in the band; heavy drinking wasn’t part of it. We weren’t those kind of people. When everybody around you is tending to go that way, I guess some folks fall into it out of peer group pressure and others are secure enough in themselves to think, ‘I’ll just make myself scarce because I’m not really comfortable doing this.’ So we didn’t. It’s just never been part of our culture to go nuts and crazy and that makes us, on the face of it, very boring people. But then Martin and I wouldn’t dream of being in a hotel room without our guitars. Just to practise and learn, and in my case, to write music.

“It has to do with temperament. We’d go through tours and be very supportive friends to each other, but we weren’t spending time in each other’s company, by and large. We weren’t hanging out, doing things together. We all had that sense of being confident just to walk out of a hotel room and take a walk and not need to be doing a rock band kind of thing.”

Of course, the onstage garb has changed over the years, much like the person wearing them. There’s the singer as pied piper, leading his troop of players and fans; the wandering spirit who blows into town; the laird of the glen; the chairman of the board; the record producer; the smart businessman who’s never far from his spreadsheets; the bardic poet; the satirist of the establishment; the man who kneels before Her Majesty to become a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire; the iconoclast; the romantic; the wise fool; the weathered eye; and the wandering man. All these and more. Will the real Ian Anderson stand up?

Consider a career as a line of light refracted through the facets of a diamond, one source split into many. Differing planes, which, when viewed in rotation, alter in depth and perception. Vivid hues collide and collage into subtle, sparkling distortions, their definition sometimes blurring at the edges, sometimes becoming lost in shadow. The music vaults across a range of styles which, over nearly half a century, has included blues-based workouts, era-defining riffs, heavy rock, long-form composition, AOR musings, repurposing traditional music, heartfelt balladry and more besides.

The 21 studio albums by Jethro Tull and the two releases issued under Anderson’s own name since 2012 shine a determined and dazzling light that explores often complex ideas about the pressures at work in society in themes that go far beyond the bluesy spark of 1968’s This Was.

In discussing his own work, Anderson is apt to be both a little self-deprecating while also speaking with the indulgence of a proud parent pleased at the achievements of their offspring. Aware of the regard in which many of these albums are held, and the influence they’ve wielded upon fresh generations of musicians over the years, he can also be unflinchingly self-critical where things didn’t quite match his standards of quality control. When asked to point to those Tull albums he would count as his favourites, he replies that his choices would probably not be that different from the fans.

- The Story Behind The Song: Thick As A Brick by Jethro Tull

- What happened the night Jethro Tull beat Metallica to a Grammy Award

- Every Jethro Tull album ranked from worst to best

- Jethro Tull Quiz

“Stand Up was my first album that was a real creative effort. Ironically, John Peel, who’d been a big supporter of the band in year one, totally lost interest in Tull with that second album. We were unveiling Stand Up, playing it live, and Peel, who was DJing at the venue, said to me, ‘This is rubbish! You should go back to what you were doing.’ I remember being really disappointed and kind of hurt by his very negative attitude about it.”

1971’s Aqualung carries a special significance for Anderson. “While it did have some big and dark riffy kind of rock songs on it, it also had quite a few very quirky, sparse tracks that I recorded on my own and the other guys then came in to overdub their parts. It was the first attempt at balancing up the contrast between big rock songs and acoustic guitar tracks. I began to focus on including my acoustic guitar songwriting and taking that on into the live performance as well. I’d not really done that up until that point. So Aqualung is an important album.”

He cites 1972’s Thick As A Brick as another substantial work in the band’s career. “It was a leap into something a bit more surreal, a bit more comedic in a way. It had that Monty Python-esque humour while at the same time putting more than a toe in the turbulent waters of progressive rock.”

With new personnel adding to the sense of energy and momentum, especially on stage where the shows became more elaborate, it was their first No.1 album in the US. “I think the Americans kind of liked it because we didn’t look like we cared too much. Some other British artists cared too much about being loved. When you do that, the chances are audiences don’t because they see through the mask, that you’re too desperate to be loved.

I think those of us who appeared to not give a damn were the ones who made the impression.”

The 1980s saw Anderson change direction, tacking away from the darker pastoral shades that had been present in Tull for some time but given full rein on 1977’s Songs From The Wood and 1978’s Heavy Horses. The improvements in digital technology in both recording techniques and instruments saw Anderson embrace an increasingly synth-orientated sound on albums such as 1980’s A, 1982’s The Broadsword And The Beast and arguably their most successful of the period, 1984’s Under Wraps.

“I think it was musically and performance-wise in almost every way quite a good album,” he says of the latter record, which he regards as containing some of his best vocal work. Yet he expresses regret about the decision not to use a drummer and rely instead on programmed beats.

“Gerry Conway had been the drummer on The Broadsword And The Beast but this next move would not have been his cup of tea at all. Looking back on it, that was a mistake and I regret doing it now. I think it would’ve been a much better album if it had been played by a real drummer.

“In a way the songs are so much better than the end result,” he says with a hint of irritation in his voice. “I feel slightly embarrassed that I couldn’t have made a better job of making that album accessible and likeable for a wider audience. There are some songs on it that I think are quite clever, but it owes too much to the technology.”

Asking artists to pick their favourite album is not unlike asking a parent to chose one child over another. While Anderson offers thoughtful and even‑handed overviews of his albums, the only one he’s quick to condemn is 1973’s A Passion Play. Recognising that it’s a cult favourite among many Tull fans, he still feels that it fails on a number of levels.

“I tried to persuade Steven Wilson that we should give that one a miss on the remix series!” he guffaws, “but he insisted on wanting to do it. I said, ‘Can we ditch all the saxophone for

a start and try to thin it out a bit to get the essential elements of the music so it isn’t so dense and impenetrable?’ Steven persuaded me that all of these things have their part and we made it a little bit more transparent and listenable, I think.

“The reason A Passion Play was like that wasn’t necessarily bad design – it was enthusiasm and over-attention to detail that made it quite a hard thing to listen to. As a record producer, I failed on that album. I didn’t impose myself on the proceedings in the way I should have done to tame it down and create some contrasts and balance. It particularly suffers from the saxophone, which is really just a damned annoying thing to have done.

“I don’t know what got into my head…” he says with the air of someone genuinely baffled by an inexplicable lapse in good behaviour in polite society, “…but there you go.”

He’s sometimes puzzled by the success of one album in a given territory failing in another. “The Broadsword And The Beast was our biggest success in Germany and yet in America, it fell completely flat. Although we were lucky to have a big success with 1987’s Crest Of A Knave due to a couple of MTV videos and radio playing them because they perhaps sounded a bit more contemporary, it didn’t

do terribly well in Europe.”

That Grammy-winning, Gold-certified album on both sides of the Atlantic took Tull as close to an AOR-orientated sound as it was possible to get, without losing their innate identity. While appreciating the clean lines of a well-crafted song, and asserting his right to go where his artistic nose leads him, Anderson accepts he has certain limitations.

“I think I learnt a long time ago that I wasn’t a very good writer of… shall we just call them ‘love songs’. Songs that are about being in or out of love. It’s all been done far better than I could ever do them, so very rarely do I write that kind of song. I’d try to somehow get closer to the inner person. I’d try to make peace with that humanity inside something,” he says, pivoting onto the nature of his approach to writing.

There are some of his songs he feels ‘twitchy’ about today. “Cross-Eyed Mary from Aqualung is not really one of my favourite songs. I have a little bit of a problem lyrically with something that is making a bit of a stereotype of a prostitute who is described in very unflattering ways. It’s not meant to be nasty but I don’t think I would write that today. I feel that maturity does help you with subjects like that.”

Appropriately enough for an ex-art school lad, Anderson at his best is a painter of portraits and landscapes, an observational songwriter capable of writing material that posits views that are different from his own personal views, in much the same way an actor inhabits a role in a play.

“Not everyone is Alanis Morissette,” he explains. “I’m not interested in telling people how I feel when I wake up in the morning, or about my personal life, my social interactions, my medical condition. We can talk about my colonoscopy happily for hours, but I’m not going to put it into a song, necessarily.”

Anderson says he writes about ‘stuff’, as in ‘the big-picture stuff’, and that writing about ‘stuff’ can be divisive and land you in trouble. He recalls the hot waters that Aqualung’s My God suite stirred up at the time. More recently, the release of 2014’s ambitious return to form, Homo Erraticus, detailing the past, present and potential future of the United Kingdom as a nexus of wildly contrasting cultures, drew concerned and sceptical reactions from some quarters.

“I remember telling somebody in essence what the album was about and they immediately jumped into a very disapproving, ‘Oh. Oh, I see.’ And I was rather taken aback, saying, ‘Wait a minute, you don’t think this is about me making a Nigel Farage-style statement in support of those who want to close our borders? How could you possibly think that’s what I mean?’ At least one person that I have a lot of respect for just seemed to think I was being a Daily Mail reader or a UKIP supporter.”

He’s still clearly disconcerted that anyone might reach such a conclusion about an album whose key theme is about the notions underpinning migration. “It’s about migration and not about immigration. It’s about the migration of ideas, the migration of humanity, commerce, industry, science. It’s about the movement of stuff without which we wouldn’t be who we are.”

Although Anderson formally laid Jethro Tull as a group to rest in 2012, he recognises that many fans still hanker for him to get back with Martin Barre. “I understand that completely. I’ve done the same myself as a fan,” he says, relating a tale of bumping into Jimmy Page in a British Airways executive lounge and asking if Page was ever going to get back together with Robert Plant. “I knew I was treading on dangerous ground to ask the question,” he says with a slightly wary edge to his voice.

There is, he suggests, a dignity in Page and Plant’s case about leaving things the way they were. Though he doesn’t say it, one senses that a Tull reunion isn’t likely to happen any time soon.

“You know that time has gone by, and those musical relationships and personal relationships, well, somehow you move on. But I don’t think you should feel bad about it or embarrassed about it. These things happen in real life. I don’t have any difficulty with anybody that’s been in the band, past or present. I think I got on pretty well with everybody most of the time. It can be nice to see them – it’s a bit like old friends and relatives when they pop round for a cup of tea. I’m hugely indebted to, and have a huge regard for, all the people I work with.”

Asked what’s been the best thing about fronting Tull or what his proudest achievement might be, he’s quick to answer. “It’s two things really. It’s having been at the epicentre of an ever-evolving and changing group of 30 musicians. For me, that feels important. It’s a very disparate group of people – different personalities, different musical styles and abilities – but without them I could never have evolved the music I did.

“Although you write music primarily for yourself, especially if you’re a singer and you’re playing a lead instrument, you’re writing for the people who are going to play it. You’re thinking about them almost all the time you’re working to develop the song. It becomes quite important and you have to recognise the way in which your music has evolved directly as a result of the personalities and the musical capabilities of those you’ve worked with.

“Secondly, it would be a sense of achievement to have lasted into senior citizenship where I don’t just have the railcard but I have most of my marbles and a full date-sheet.”

It was the American author Paul Auster who, when asked about entering the winter of his years, replied that he was living in the present, thinking about the past and hoping for the future. The same can be said for Anderson as he discusses his life’s work. Has he ever considered writing an autobiography?

“I’ve been asked several times to do that but on the one hand, it’s not quite over yet. Writing something that would seem to be summing up almost 50 years of a musical career, or 70 years of life, would be a gargantuan task in itself, but because it’s not finished, I think it’d be closing the door prematurely.

“Let’s face it, the kind of books we enjoy reading are the salacious ones full of muck-raking and name‑calling, describing the excesses of the rock’n’roll lifestyle. My book would just be incredibly dreary and boring. Much as I have a not endless but a substantial fund of very spicy and naughty stories about other people in the business, my lips are sealed.”

Despite being eligible for a pensioners’ railcard and bus pass, Anderson has no intention of retiring. “I think most of us who do what I do don’t really think seriously about there being a real cut-off point. You know there’s going to come a time when you just can’t do it physically or mentally – whatever hits you first. You know it’s going to end, and it’s sometime relatively soon. But as I said to my son last night, it could be 10 years away, it could be one year away. We don’t really know. We look ahead a year or two at a time and that’s what I do.

“I enjoy working and why would I want to quit? If I was driving a racing car, or was a tennis player or an astronaut, then the game’s up – it’s over. I’m lucky that my profession is one that you can more or less take with you to the grave with my boots on. They’ll carry me off the stage.”

He pauses for moment, perhaps contemplating the image of a fallen artist, before a more practical thought springs to mind. “Hopefully it won’t be after the first song, otherwise everyone’s going to want their bloody money back!”

Jethro Tull – The String Quartets is out on March 24 via PledgeMusic. See jethrotull.com for more information.

MY TIME IN TULL…

MICK ABRAHAMS (1967-1968)

Best thing about being in Tull?

“They used to let me sit in the front of the van when we were on the road.”

Funniest Moment?

“Walking around Woolworth’s one day with Ian Anderson. We were both trying lampshades on our heads. Ian looked beautiful and I didn’t. An assistant came up to me and said, ‘Are you mad?’ So I replied, ‘He is, but I’m not. Now get us a mirror so we can see which lampshade looks best as a hat.’ And she got us a mirror!”

Favourite Tull album you played on?

“This Was.”

CLIVE BUNKER (1967-1971)

Funniest moment?

“Our set in America got longer and longer, and Ian’s flute solo would also get increasingly stretched out. So, what happened on one tour was that our tour manager, Eric Brooks, would bring out a card table and two chairs, and set it up behind Ian when he went into his solo. Martin Barre and I would sit down and play cards. Eric then came up with a pot of tea for us. All this was going on while Ian played, and he had no clue what was happening. This went on for a couple of gigs, with Ian puzzled as to why the audience was laughing as he played! Then one night he turned round and saw us – but fortunately he thought it was hilarious.”

Favourite Tull album you didn’t play on?

“Roots To Branches.”

JEFFREY HAMMOND (1971-1975)

Best thing about being in Tull?

“Having the good fortune and privilege to play a small part in their journey. But unquestionably the camaraderie between us at that time was what I value the most.”

Worst thing about being in Tull?

“Having to share a bed one night with John Evan in an overbooked hotel in Vienna!”

Favourite Tull album you played on?

“Thick As A Brick.”

PETER-JOHN VETTESE (1982-1989)

Best thing about being in Tull?

“It has to be dealing with Ian Anderson. From the time I joined the band, we had a gentleman’s agreement that he would ensure I always got publishing royalties for anything I had contributed to Tull songs. He told me this even before I knew what publishing was. And to this day, he has kept his word. His influence on me, and his kindness, has probably been more than I deserve. His moral and ethical compass is unquestioned.”

Favourite Tull album you played on?

“That’ll be The Broadsword And The Beast, which is a good transitional album from where the band were to where we wanted to go.”

TONY IOMMI (1968)

Best thing about being in Tull?

“Ian had great discipline, and was very professional in how he went about things. He put me on the right road and when I went back to Brum, I made sure Black Sabbath became a lot more organised in everything we did.”

Favourite Tull album?

“This Was. It made me think about wanting to join the band.”

DAVE PEGG (1979-1995)

Best thing about being in Tull?

“The money!”

Funniest moment?

“Peeing in a beer bottle backstage, and not realising that the lighting was casting my image (luckily size enhanced) onto the white sheet side-stage, in full view of the audience!”

Proudest moment?

“Winning a Grammy in 1989 for Crest Of A Knave.”

Favourite Tull album you didn’t play on?

“Heavy Horses.”

DOANE PERRY (1984-2012)

Worst thing about being in Tull?

“Some of the ludicrously early mornings. I was envious of certain band members’ ability to get back to the hotel and go straight to sleep by midnight. I could never do that as I was too energised after a performance to get to sleep until at least three or four am. We would often be up at seven or eight am for the lobby call, followed by travel to the next city, lunch, sound check, gig… and repeat.”

Funniest moment?

“When our five-foot-two Irish and rather gnomish-looking beloved crew member Colm appeared, wearing a little green elf hat. He was dancing around a 12-inch-high replica of Spinal Tap’s Stonehenge, to the utter delight of our audience, while Dave [Pegg], Maartin [Allcock] and I performed an unplugged part of the set, albeit in happy oblivion. The audience roared with laughter.”

Favourite Tull album you didn’t play on?

“A.”

JONATHAN NOYCE (1995-2007)

Best thing about being in Tull?

“My bandmates and the music. You can’t have one without the other.”

Funniest moment?

“At the end of a tour, the last gig of the year, post-show at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles. I donned a monkey suit, the gift of an old friend, which seemed the most appropriate way to celebrate a good job done and our soon-to-be homecoming. This was arguably the best/worst – delete accordingly! – time to be introduced to the head of EMI. We shook hands. I made my impression, then my excuses and exited. Stage left.”

Favourite Tull album you didn’t play on?

“Minstrel In The Gallery.”

GERRY CONWAY (1982-1988)

Best thing about being in Tull?

“I had misgivings when I joined as to whether I could play some of the older material with complex arrangements but when I found that I could, I greatly enjoyed playing the music.”

Proudest moment?

“When mum and dad came to see us at Wembley Arena.”

Favourite Tull album you played on?

“The Broadsword And The Beast.”

Ian Anderson's Top 10 Jethro Tull Songs

Jethro Tull - The String Quartets album review

Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson on politics, God, and Ritchie Blackmore's clothing