Following his first four years as the frontman with Deep Purple, Ian Gillan and his band Gillan emerged as one of the most popular and colourful rock groups of the late 70s and early 80s. With a high-energy sound that was turbocharged with melody, few will forget their run of appearances on Top Of The Pops for hit singles such as No Laughing In Heaven, Mutually Assured Destruction and their riotous revisions of Elvis Presley’s Trouble and Stevie Wonder’s New Orleans.

From an alarmingly non-conformist visual image to Ian’s often quirky lyrics, which included rhyming ‘ultrasonic’ with ‘gin and tonic’, and their choice of subject matter (No Laughing In Heaven was a largely spoken-word paean to a sinner who cleans up his act to avoid going to hell, only to discover that up in the clouds partying is forbidden), Gillan – the band – rarely trod the conventional path.

They also grafted considerably harder than the average band, traversing the length and breadth of the country. Often revisiting Purple’s Smoke On The Water at a time when that band’s presence was sadly missed, it felt like Gillan – the man – was presenting us with a bucket-list moment that otherwise might never have been realised.

A new seven-disc anthology, 1978-1982, brings together their studio albums along with B-sides, standalone 45s and out-takes, from the band’s short but very sweet run. And although Ian Gillan admits that “things were not so good at the end”, he says “the memories are definitely positive”.

Gillan the band’s forerunners the Ian Gillan Band had come to an end when keyboard player Colin Towns brought in a song called Fighting Man that was ridiculed by the rest of the group.

“The end of the Ian Gillan Band had been coming,” reflects the singer. “Things weren’t right, but it was so difficult because I was working with my heroes. I idolised Gus [bassist Johnny Gustafson, ex-The Merseybeats, Roxy Music] for being so talented. We needed to get back on track, but Ray Fenwick [guitar] and Mark Nauseef [drums] were happy with that jazzier type of rock, though I wanted to play rock’n’roll. Fighting Man was a catalyst. It was a simple song but it had a certain profundity, and when those two took the mickey out of it, that was it for me.”

So you sacked yourself from your own band?

“Yeah. I just left.”

In forming Gillan, Colin Towns had to be there.

Colin was pivotal to it all. Rock’n’roll is good, but you also need a simple platform for virtuosity to shine. Colin kept that gravitas. He added texture and dynamics along with all of those musical elements.

Bernie Tormé was such a great guitarist.

Exactly. We had five guys that played equally well but Bernie was the one that stood out. I had spotted him some time earlier. He was amazing, and I marked him down for the future.

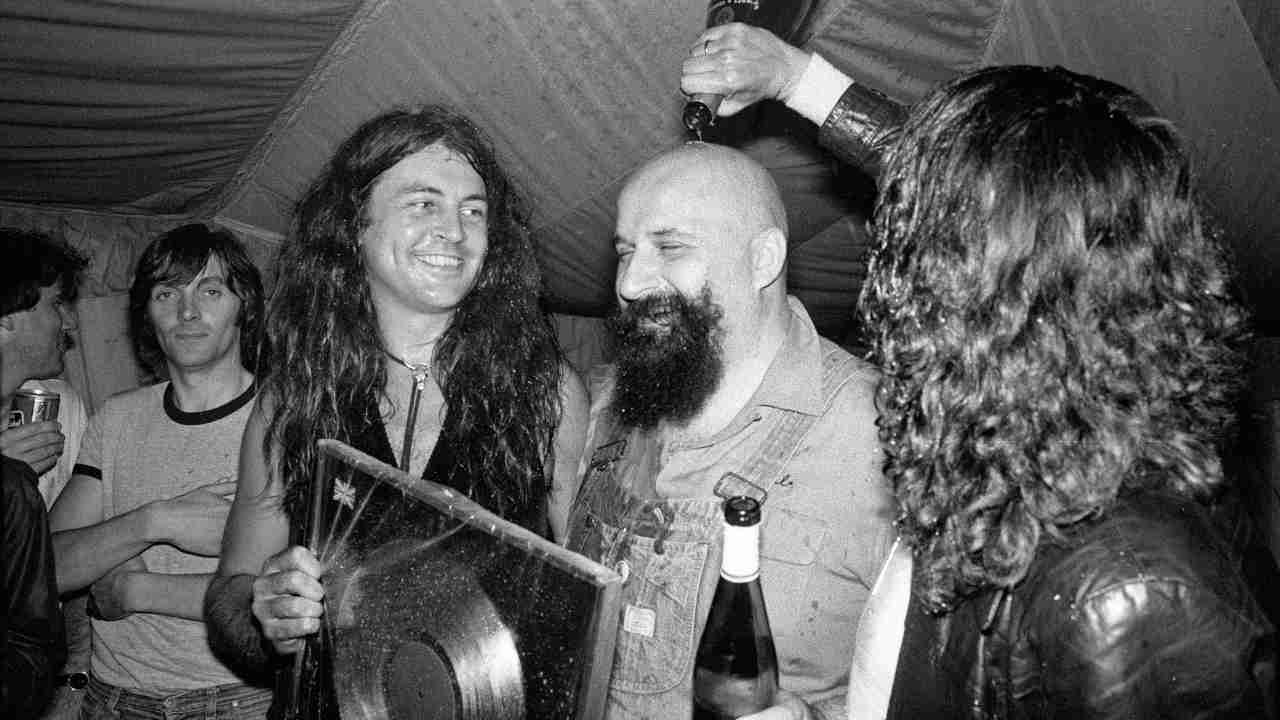

Shaven-headed man-mountain bassist John McCoy was almost a cartoonish character.

John was great. He made a big impact, just what we needed. He offset Bernie on the other side [of the stage].

McCoy projected quite a threatening presence.

He was ferocious looking, kind of manic. The kids either loved or were scared to death of him. John was a very, very good showman. His contribution to Unchain Your Brain [the opening track of the album Glory Road] was probably more important than all of the other guys because his bass line really set up that song. But you say ‘cartoonish’, and I suppose he was.

Here’s a random memory: on the Magic tour in 1982, McCoy learned over the barrier to slap an astonished audience member in the front row who had dared to boo his bass solo.

I don’t know about that incident. But I did learn that John was prone to violence, and I had to put a stop to that.

And last but certainly not least, drummer Mick Underwood (who died in July 2024).

Mick was an absolutely fantastic drummer [he had played in Episode Six with Gillan and Deep Purple bassist Roger Glover, preceded by a spell in The Outlaws with Ritchie Blackmore]. I first met Mick when I was still at school, at the bus stop at Henlys Roundabout [in West London]. He was carrying a briefcase with a pair of drum sticks sticking out. Along with Mitch Mitchell [of the Jimi Hendrix Experience] and a few others, Mick was another drummer taught by Jim Marshall. I make my own judgments, but when [Deep Purple drummer] Ian Paice says Mick is a great drummer, then it must be true.

The band’s first songs were released in Japan only, as the album Gillan, in 1978, and you’ve freely admitted that the following year, when it came to looking to get a record deal in the UK, you “couldn’t get arrested”.

That’s correct. My agent and later manager Phil Banfield and I, along with Phil’s partner Carl Leighton-Pope, sat around a desk with three telephones and called every record company listed in [entertainment industry bible] Kemps Directory, and nobody was interested. EMI [at the time still Deep Purple’s label] replied: “Rock bands are history.”’ Stiff Records simply told us to fuck off.

How did that make you feel?

I believed that we had every reason to feel confident, as we had a thirty-eight-date UK tour sold out. However, the fashion was that rock’n’roll or hard rock was out of the window and punk and new wave was the thing.

I understood what was going on in the industry. I know how the business goes. The music business is full of shattered dreams. I looked at things with a longer-term view. I had spent five years chasing dreams with Episode Six. We made something like thirteen singles. Purple was a different type of band. We quickly found our niche and avoided chasing fashion. But I’m a realist, I knew it would be difficult.

In the end a small label called Acrobat took you on, only to go bust as the album Mr Universe reached number eleven.

They had no money. Mr Universe got into the charts, but the following week it disappeared because the factory [pressing plant] bill hadn’t been paid. Had that not happened we’d have gone top three. It was frustrating, but [the incident] gave us just enough – just enough – to make the other labels think: “Okay, maybe we were wrong.” Virgin came in for us and we had a fantastic relationship with them.

In music weekly Sounds, Geoff Barton awarded five stars out of five to Mr Universe, hailing it as “heavy rock for the 1980s”.

Did he? I never read reviews. They don’t interest me.

Around Christmas 1978, Ritchie Blackmore visited you with an invitation to join Rainbow. Although you declined, he still played with Gillan at the Marquee club in London. Were you tempted by his proposition?

No. The reason I had left Deep Purple was that they were moving into a kind of territory [later filled by Rainbow]. I didn’t want that. I wanted a group with grit, excitement and edge. Also one that had balls. That’s no reflection on Ritchie, who was a fantastic, amazing guitar player – in fact I said: “You can come and play in my band if you want” – but Ritchie has firm ideas about how things should be, and there were things that we disagreed on.

With the line-up stabilised (guitarist Steve Byrd and drummer Liam Genockey had contributed to Mr Universe) and a reliable support network behind the group, Gillan’s major-label debut, 1980’s Glory Road, needed to be a masterpiece. And it was.

Thank you. I still consider that record among the best I’ve ever made.

The free companion album For Gillan Fans Only was full of the band’s irrepressible, zany humour, along with some great songs.

People seemed to like that. Every band, if they’re enjoying themselves in the studio, will have a lot of out-takes. Chucking them away would be foolish, so why not bundle them together and make them available to the fans?

Let’s not forget that Gillan had a lot of hits – six Top 40 singles in all.

That was lovely. As I said, Virgin never failed to put their weight behind us. The managing director said that Gillan saved the company. They were going through a bad spell at the time, though I had no idea of that until later on.

For us, the viewers, those spots on Top Of The Pops felt iconic. Your hair grew much longer, and with Bernie throwing his shapes the performances seemed charged with boozy bravado. You seemed to be thumbing your nose at the likes of Spandau Ballet and Culture Club, almost proud to represent the great rock community.

Not in slightest, no. I don’t care what you call it – rock’n’roll, rock, hard rock – it doesn’t matter. To me, rock’n’roll is not about a style, it’s about an attitude. There have been a lot of definitions I can’t relate to, let’s not go there. But that’s how I’ve felt all my life. Categories are irrelevant to me.

All the same, rock music used to get such short shrift on national television, so it really felt as though Gillan were flying the flag for rock.

Not to me. We never ‘thumbed our nose’, as you put it, to anyone. People often talk about the relationships between Sabbath, Zeppelin and Purple in the early days, and the magazines and media have always tried to pretend there was some sort of rivalry. That was rubbish. We would drink together. We were mates.

I used to go to the Camden Palace and drink with Boy George. I loved Culture Club. We had no competition with them. [With a quiet chuckle] I’m not quite so sure about Spandau Ballet.

For you personally, was that second phase of stardom a source of pride?

I don’t pay much attention to that side of things. I love every minute of what I do; I’m like a kid in a toy shop. I remember my first [support] tour with Dusty Springfield, just as I recall playing the Marquee for the first time and my debut with Deep Purple. Working with Gus [John Gustafson, in the Ian Gillan Band] was special, as was meeting Cliff Bennett [of Cliff Bennett And The Rebel Rousers] for the first time. Those were my thrills. So no, I never appraised or analysed things in the sense that you mean.

Gillan achieved their fame the hard way. At the time of Glory Road, the band were playing around two hundred gigs per year. You said then: “Gillan are a non-stop touring band. There seems no reason to change that. I like this life.” Was that completely truthful? Nobody likes being away from home for that long, surely?

[Slightly vexed] What do you mean? I still do it [with Deep Purple].

But not two hundred gigs a year.

We [Purple] started this last leg [of touring for the album =1] in May and I got home on Sunday [this interview took place in November]. So pick the bones out of that. I think it was less than two hundred shows back then, but let’s not split hairs. The intensity of the touring hasn’t diminished one little bit. Apart from the three years I left Purple, 1973 to 1976, I’ve been on the road since I was a kid. It’s my life.

The next album, 1981’s Future Shock, which featured the hits No Laughing In Heaven and a remake of R&B standard New Orleans, entered the UK chart at number two. Do you consider it as strong an album as Glory Road?

It depends what you’re judging it on. It’s like all of the records I’ve done, I can’t say I like all of the songs but I’ve got to love them because they’re my kids. Overall I really like that album, though I thought the drawing [of the band in ‘space age’ garb] on the cover was absolute crap. Having said that, the photos inside were amazing. I get a smile when I think of that record.

The old Gary U.S. Bonds hit New Orleans was possibly a strange choice for Gillan to cover.

I disagree. That song is part of my heritage, mate. I’d sing: ‘Hey, hey, heh, yeah’ and the audience would always respond.

Double Trouble was a half-studio, half-live set that made the UK Top 10.

I don’t have much interest in my own live recordings, but I love that our performance at the Reading Festival [in 1981] was included in Double Trouble. Those versions of No Laughing In Heaven and Mutually Assured Destruction bring back such wonderful memories. The crowd that night was just awesome.

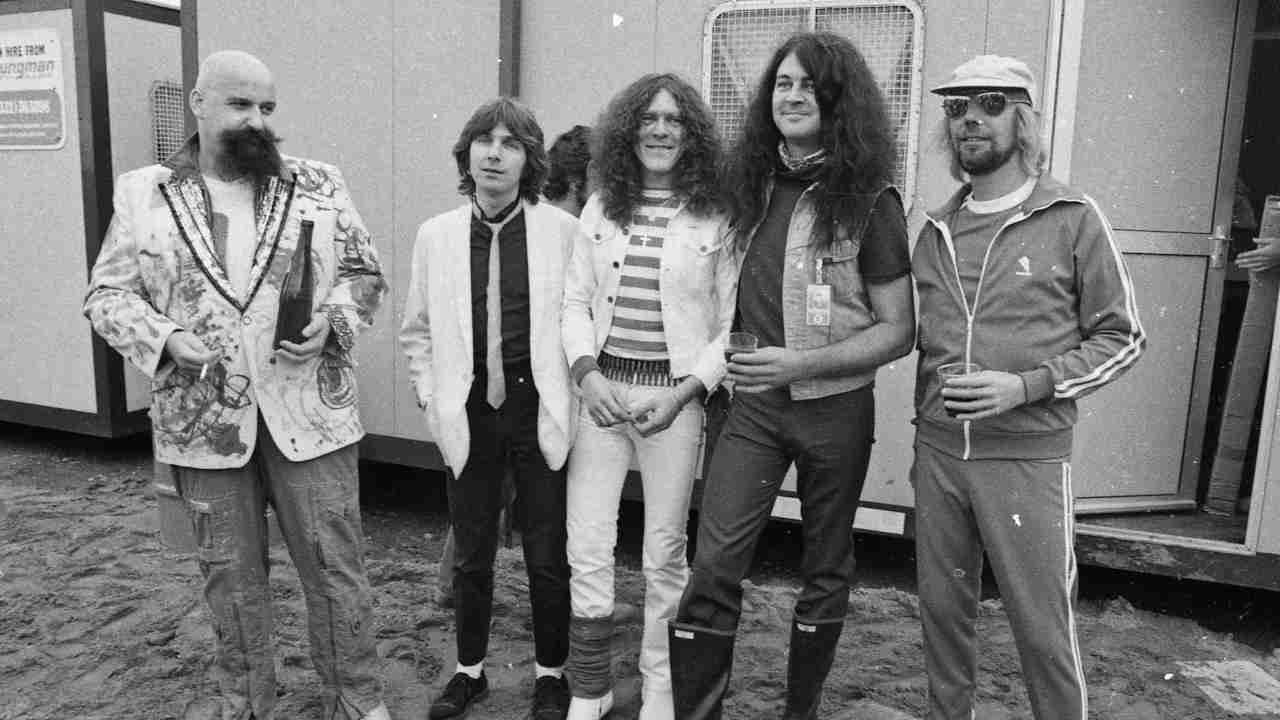

You appeared at Reading for four consecutive years (the Ian Gillan Band in 1978, Gillan in 1979, then as special guests in 1980, and headlining in ’81). For us fans, Gillan really did feel like a band of the people. Were you proud of that?

It’s an honour [that someone might think like that], but you’re putting words in my mouth. I’m a passionate and intense person but I don’t get very emotional about such things. The most excited that I would get is ‘mildly content’.

Bernie Tormé suddenly leaving the band in 1981 felt like a real problem, but Janick Gers was brought in at quick notice.

It was a problem – for about five minutes. Virgin called us back from Germany to do Top Of The Pops for No Laughing In Heaven, but when I talked to the guys I got a really negative reaction. The label was paying for our flights to promote the new single, but Bernie insisted: “I’m not going, it’s a day off.” To which I replied: “If that’s your attitude, Bernie, it’s going to be more than a day off for you, mate. Because the van arrives at ten a.m. and anyone who isn’t on it is no longer in the band.” He wasn’t there, so Janick came in.

You’d seen Janick playing with White Spirit on the Glory Road tour?

Yeah. I filed him away [in my mind] for future reference. Bernie was fantastic, don’t get me wrong, but he was also quite volatile. Janick was much more placid. More of a steady guy. Janick walked on stage and [personality-wise] he changed entirely. I like people like that. It can be difficult when someone is still performing when they come off stage.

With respect to Janick, who of course went on to join Iron Maiden and remains there to this day, were Gillan as good without Bernie?

You can’t compare the two styles. Just as Bernie did, Janick brought something [of his own] into the band. He was a stunning performer, he looked amazing. People listened to him. The band loved him because he fitted in well, in addition to projecting his own individual image and sound.

What are your views on Magic, the final Gillan album?

It [the line-up change] really worked. Bluesy Blue Sea is a really important song, one of my top five from the whole Gillan period. Demon Driver is another song I used to love doing live. I had a great time writing that album at a village hall down in Musberry [in Devon]. At that point the atmosphere in the band was okay.

All the same, it’s been speculated that hints of things coming to an end were hidden in song titles such as Caught In A Trap, Long Gone and Living A Lie. Is there any truth at all in that, or is it complete bollocks?

[Laughing but sounding frustrated] It’s complete bollocks. I still get that all the time. People will say: “Oh, this is a very personal song” even with a story of unrequited love that has been written ten thousand times before, albeit with a different twist. I can’t tell you how many of my songs people have thought were about Ritchie. In fact there was only one.

Are you willing to name it?

No. But it was on Who Do We Think You Are [Deep Purple’s 1973 album, Gillan’s last in his first spell with Purple].

Gillan’s final tour was a long, thirty-eight-date trip around the UK. It was announced before the first date that afterwards you would need to stop singing for nine months because of problems with your voice.

We had to cancel a few shows because I had laryngitis. One of my most memorable shows was at Portsmouth Guildhall. The fans sang the entire show for me – they got it. That’s how special they were. Two separate consultants told me to have an operation or take six months off. I didn’t believe that. After cancelling two or three more shows I got a bit of a croak back, and we managed to hobble through the rest of the tour.

After the Gillan band had finished, I was in Germany and was introduced to Professor Theobald from Munich University Hospital. He looked at my throat rather more holistically than the other two gentlemen had. He told me it was massively inflamed and infected. I had been singing around corners, basically. My tonsils were removed and I’ve never had a problem since. So that’s the history. Anyone that doubts it can go take a hike.

Aware that the band was ending, what was the atmosphere like backstage as the tour headed towards its final date, at Wembley Arena?

I must give you some more background information. First of all, when I started Gillan I said: “Let’s share everything.” I didn’t want to be a boss with backing musicians. It had to be a band. But that meant sharing not only the profits but also the expenses, and not everyone understood that. We were working in my studio [Kingsway], often for free. Basically, I was financing the band. Everything’s on record, in the end it went to court. I was right and they were wrong. A lot of harm was caused. It was led by McCoy and followed by Underwood, neither of whom I will say a bad word against as far as their musical contributions go. But they upset the apple cart and the rest of the guys realised what was going on. There was violence, and they brought that into the studio. By that time I’d had enough.

The other accusation is that I wrapped up the band to join Deep Purple. I’ll tell you exactly what happened there. When we played Hammersmith Odeon I went for a curry with Rodney Marsh [footballer who played for England in the early 70s, and has a huge love of rock music]. During our meal, Rodney had said: “Gillan are a great band, but not as good as Deep Purple.” That got me thinking, especially as I was disillusioned with what was going on.

So the next day I called Jon Lord and told him I was winding up Gillan, and what did he think the mood would be [for a Purple reunion]. Jon said he would be interested and would ask around. When he called back, Jon said Ritchie was up for it but had commitments for the next year. So that’s what happened. There was no premeditation, it was just that I could see a gap coming. After that last Gillan date at Wembley, I got a call from Tony Iommi and I went for a drink with him. That’s how I ended up in Black Sabbath.

Had everything not imploded following that conversation with Rodney Marsh, was there a scenario in which Gillan could have continued?

No way. But it was Rodney’s Deep Purple comment that triggered those thoughts. I literally had not considered the idea. However, I had already made up my mind that I had had enough of McCoy and company.

Following an exceptionally bitter split, John McCoy wrote a song called Because You Lied for his next group, McCoy, which they recorded with Colin Towns on keyboards. The song lamented your joining of Sabbath. Did you hear it, and what did you think of it?

No. But I read all about it, don’t worry about that.

The words were particularly scathing: ‘Can’t wish you luck in your adventure, not while you’re digging your gold mine/You played with lives, and I’ll just mention that the roof fell down on mine.’

You can interpret that any way you like. I read jealousy. Jealousy and insufficiency.

If you happened to encounter John again, and he was willing, would you bury the hatchet and make peace with him?

[After a long pause] I don’t think so. He caused so much trouble for my manager, Phil Banfield. [What McCoy did] was unforgiveable. It made me really angry. I’ve been with Phil since 1979, his professionalism is unchallenged, and McCoy was outrageously wrong.

In a more general sense, within the context of your life Gillan was a hugely important period.

Oh, massively so. It was a development period for me. I learned so much from so many people – including McCoy. It gave me so much in so many ways. Apart from any profit!

Gillan: 1978-1982 is out now