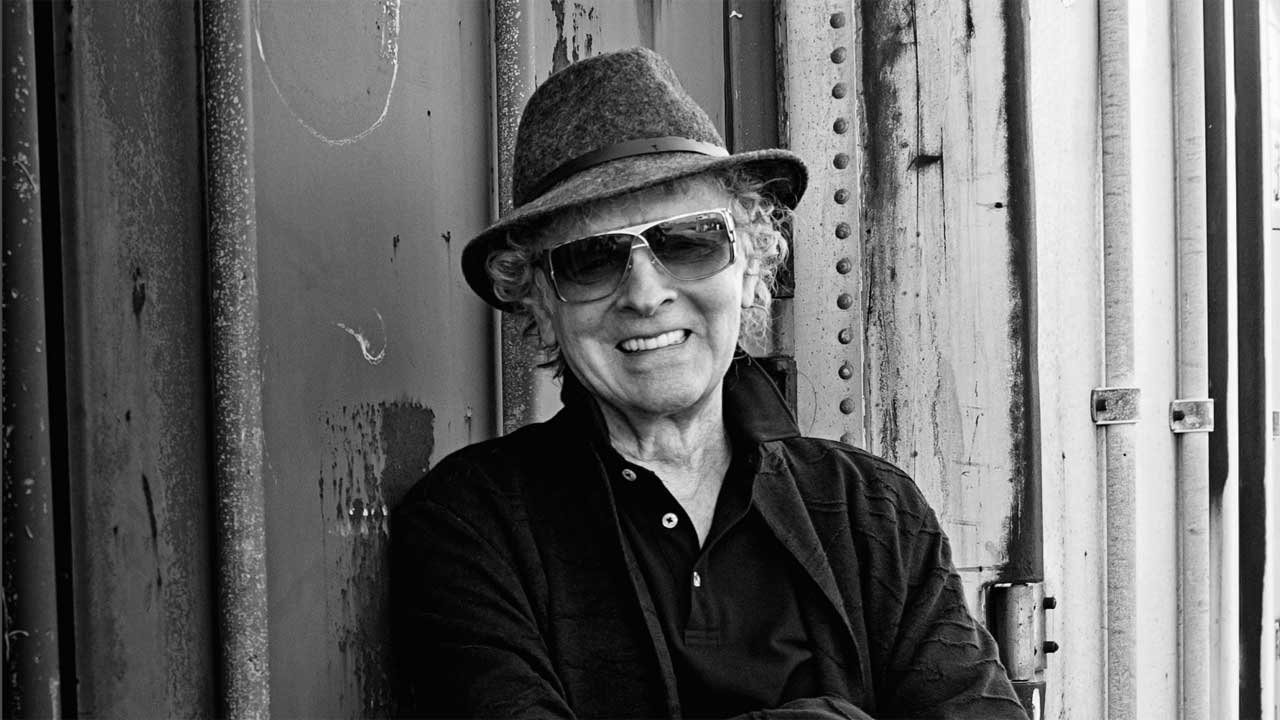

"The whole thing’s been a fluke,” says Ian Hunter, “a lovely fluke.”

Back in 2019, even Ian Hunter thought that he was finished. He had released his last solo album, Fingers Crossed, in 2016. That same year saw the release of Stranded In Reality, a 30-CD boxset of his solo material that felt like a whopping great full stop to an amazing career. UK and US tours with Mott The Hoople in 2019 seemed to take things full circle.

To mark his 80th birthday, he did five nights at The Winery in New York City, playing through his back catalogue.

“I thought that was it,” he admits. But Ian Hunter underestimated himself. Def Leppard manager Mike Kobayashi came to The Winery shows and offered to manage him. So there he was: 80 years old with a new manager – a guy who manages one of the biggest rock bands in the world.

Then in 2020, Covid hit, he says: “And me and a million others went downstairs into the basement and started writing songs. Because there was nothing else to do.”

Three years later, Hunter has a new record deal – with Sun Records, no less, the label that inspired him to get involved in rock’n’roll in the first place – and we have Defiance Part 1, ten new songs featuring a Who’s Who of rock, including some of the last recordings from Jeff Beck and Taylor Hawkins, as well as input from Slash, Billy Gibbons, Ringo Starr, Joe Elliott, Metallica’s Robert Trujillo, Heartbreaker Mike Campbell, Todd Rungren, Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, Dean and Robert DeLeo of Stone Temple Pilots, Aerosmith’s Brad Whitford, movie star musos Johnny Depp and Billy Bob Thornton and more.

It’s a thrilling record that reminds you of why you like rock’n’roll in the first place. Smart, ballsy, touching, defiant.

“It’s an intelligent racket,” shrugs Hunter. “We sent the right tracks to the right people.”

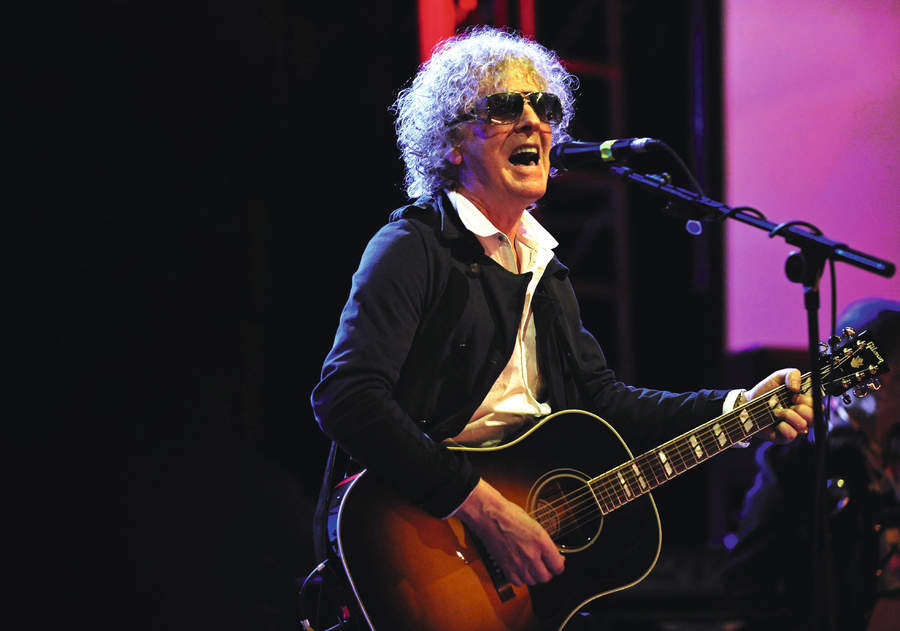

So here he is at 83 with his foot on the monitor delivering one of the hardest rock albums he’s done in years, with guys from Guns N’ Roses and Metallica. “Why not? That’s why the album is called Defiance. ‘What’s he doing making a rock’n’roll album?’ But it came naturally. There was no plan. I just kept writing and that’s what came out.

“I just wake up in the morning and there’s an idea. I don’t write for business. If it comes, it comes. And I just got on a tear."

So Covid was an unexpected inspiration?

Well, I’m lively. And if there’s nothing else to do, you might as well. Plus, it was like: I shouldn’t be doing this at my age, so that’s another reason to do it. When we came off the road with the Rant Band, it’d been 10 years of album after tour and it felt like time for a change. I wasn’t quite sure what that change would be but, you know, you just sit down and write. And then I had Mike, and there’s another guy, [photographer] Ross Halfin – do you know Ross Halfin?

I do know Ross. Very well.

Ross has been a mate of mine for a long time. I’m one of the few people he hasn’t fallen out with.

Oh, give it time, Ian.

I’ll tell you why I like him: because he tells you what to do to take a good picture. I’m no good at that. He’s like: “Chin up, chin down, move this way, move that way”. It’s great to do that because then you don’t have to think about it. But between him and Mike Kobayashi, they were saying, “How about somebody else doing your songs?” And I sent them a couple and then it was like, “Well, Slash likes this one. Billy Gibbons will do that one.”

And that’s how it started. I kept writing and they kept getting people involved. And Andy York, who was co-producer with me, we suggested people too. I suggested Ringo, because [first single] Bed Of Roses is his groove. It’s a headnodder. He said, “Well, if I like it, I’ll do it, if I don’t, I won’t.” Fortunately, he liked it. It was all off-hand. The whole thing’s been a fluke – a lovely fluke.

But slowly but surely a lot of people were interested or involved or, you know, Ross forced them [chuckles]. And then sometimes you had to wait because people were out touring. I had no idea these people even knew who I was.

Ross is really good at bringing people together like that. Back in 2016, we held the Classic Rock Awards in Tokyo and Ross put the house band together – Joe Perry, Johnny Depp, Dean and Rob DeLeo and so on.

I met him at the Classic Rock Awards. I didn’t know the guy, but I liked the way he treated you, the way he told you what to do.

I’ve known Johnny Depp for a while and he was in the studio with Jeff and he said, “We’ll do a couple”. We sent them a couple of songs. One’s on the first album, one’s on the second. Johnny asked me to do a Vampires gig, so I came to New York and that’s when I met Robert DeLeo. And he was a lovely bloke. So I rang him and we went back and forth. His brother Dean was interested and Dean rang and said, “Our drummer would like to do it as well.” So things developed that way.

Did you know Jeff Beck before this?

I’ve been out with Jeff one night because, again, Ross said, “Why don’t you come down for dinner?” And it turned out to be with Jeff and Johnny Depp. And we had a great night out, went for an Indian.

So all those years you were a part of the sixties and seventies rock scene, you never met Jeff Beck?

I met him once in New York. But I didn’t know the guy. The thing with Jeff is: it’s got to be absolutely right. So even when he’s done it, he’s got to sign off on it. We were worried for a while because he didn’t sign off. And that’s another thing. It’s not only getting these people to do it – that’s the easy bit – it’s the managers and the lawyers, after the fact. But he finally signed off just before Christmas. And then he got ill over Christmas. That was scary.

It was such a shock.

It was a shock. Same with Taylor. I mean, I didn’t really know these people. I had met Taylor briefly in a LA in a hotel. He said, “You were in that band whaddyacallit?” And I went, “And you’re in that band whaddyacallit”. He said, “If the Foos ever come to New York, will you get up?” And I said, “Yeah.” I never did. It was just one of those things, a guy you meet on the way. Then my manager Mike’s saying “Oh, I had him on the phone for about an hour and a half – he knows everything.” And that’s when I started talking to Taylor.

He wanted to do it all. We sent him some tracks and he rang me up and said, “Look, I want to do all of this.” But Covid started easing off and the Foos started going out again, so in the end he did seven tracks. Three on the first album and four on the second. He was gonna do them all. Amazing guy.

He seemed like a real music fan.

He was going on about Standing In My Light off Schizophrenic [You’re Never Alone With A Schizophrenic, 1979, Hunter’s fourth solo album]. That’s why I say a bit like Joe Elliott, because Joe’s encyclopaedic. Taylor was the same. Such an upper to talk to. You could talk to him for hours. Full of life. He just came off as a guy who was just so full of enthusiasm, ready to go 24 hours a day. It was a real shock to me.

And what did he bring to the songs?

He’s a great drummer. He’s one of the best in the world. I sent him one song, a ballad called Angel. All he was supposed to do was drum on it. It came back with harmonies, he’d put a lead solo on the back end of it, he got Duff McKagan of Guns N’ Roses to do the bass on it. And the harmonies he did! Andy and me were like: “Well, it’s done.” An incredible guy.

What about Robert Trujillo from Metallica?

Robert did a movie about Jaco Pastorius [famous as the legendary bassist for Joni Mitchell and Weather Report, some of Jaco’s first recorded work was with Ian Hunter], and I did an interview with him. During the course of that he said, “If anything ever comes up, I’m happy to do something.” So we sent him Defiance, which Slash was already on, and he used Jaco’s original fretless bass, the same one that Jaco had used on All American Alien Boy [Hunter’s second studio album from 1976]. So that was a neat little story.

The combination of the two of them is absolutely great. There’s a point at the end of the first solo that Slash does on Defiance where they both kind of finish up the solo together. It intermingles, even though they came from different studios. That happened a few times. A lot of flukes happened. We were dead lucky.

This is obviously a different way of working for you. You’ve spent years working with people in the studio, looking them in the eye.

And going on last. Here I was going on first. They weren’t supposed to be the final vocals or anything but then Dean DeLeo’s calling up saying, “Don’t change the vocals!” Because they were playing to the vocals. We did that on Once Bitten Twice Shy [Hunter’s only solo UK top 20 hit, from 1975] – the drums went on last. It’s not a bad way to do it, because then everybody understands the lyric. Normally when you go in, nobody knows what the lyric is, they just play the song. I remember [Mott bassist] Watts saying, “I never knew what you were on about!” He was just learning how to play it.

The Rant album [2001] seemed to usher in a new Ian Hunter, one that was more rootsy: acoustic rock’n’roll, with piano, a bed of acoustic guitars, that sort of instrumentation. But Defiance is very electric guitar rock, isn’t it?

It’s a rock’n’roll album. It’s probably out of its time but that’s what it is.

It feels like you hit a theme and maybe working with these guys gave you the confidence to rock a little bit harder. Because for all you’re saying, there was no plan, it feels perfect: it opens with a song called Defiance and closes with This Is What I’m Here For – a defiant rock song.

You’re right. As these people came in, I got more excited. And it came quicker because of that.

Tell me about This Is What I’m Here For. What are you here for?

To play music, y’know. I was 18, 19 when I heard Jerry Lee Lewis. Up until that time I didn’t have a clue what I was here for. Didn’t have a clue. You’ve got the factory and that’s it. All of a sudden, I heard Whole Lotta Shakin’. “Ah, okay – that’s what I’m here for.” The only trouble was, I wasn’t very good so I had to work at it.

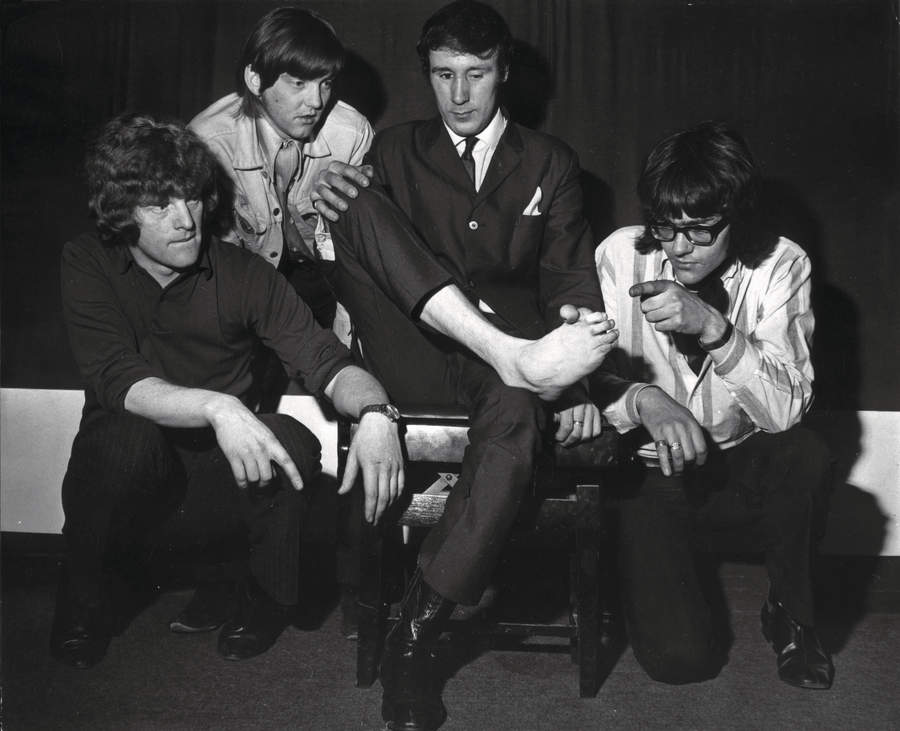

I was a bass player. We did a lot of work in Germany and places like that, where you played every night, and slowly but surely, I got started. I played bass with Freddie “Fingers” Lee and he was like, “You write a decent song.” I wasn’t thinking about singing, I was just thinking about trying to get into the songwriting business. And I got into it – I was at [publishing company] Francis, Day & Hunter as a songwriter. Remember Dave Berry? He did one of mine [Berry recorded a Hunter song called And I Have Learned To Dream in 1967] and Nicol Williamson, the actor, he did one [Season’s Song, 1970] That’s before Mott.

I was staff writer, just out of the factory, and then into Mott. And when I got into Mott, the two writers were Mick Ralphs and Pete Watts. Pete was lazier than I was, and he was also the good-looking one in the band, always off with models. So he was like: “You do it.” None of us knew at the time that publishing was where the money was. Pete was like, “I’m busy, you do it.” That’s how Ralpher and me got to be the writers in Mott.

Richard Jobson of the Skids told me that he went to see Mott supported by Alex Harvey in either Edinburgh or Glasgow. He said that Alex Harvey left a hole in the stage – I guess he smashed a guitar or something – and you guys had to play around it.

[Laughing] I remember Alex! What’s that place with the big high stage in Glasgow?

Glasgow Apollo [then called Green’s Playhouse].

The Apollo, yeah. They used to give you a statue if you sold it out. Alex Harvey supported us there – his brother was there and his mother, I met them all in the afternoon – Alex was lovely. That place: the first thing they showed you was the back door out of the dressing room. That was your escape route. Because if they liked you, they would go like, “Yer fucking brilliant!” and they’d smack you. And if they didn’t like you, you were dead.

The guy came in to give us the award for selling the place out, and he’s got a bandage on, with blood coming through the bandage. The front doors were glass and they’d opened late that night, so the crowd had used him as a battering ram to get in. He was apologetic! I’m like, “You’re bleeding!” But that was the norm.

The Sensational Alex Harvey Band and Mott The Hoople were two of the few older bands that the punk generation looked up to and accepted.

I didn’t think it was gonna be like that. I thought it was gonna be like: “Old guys out!” We went to see [punk band] Chelsea one night and Mick [Ronson] got chased. But I was alright. Everywhere you went, everybody adored Mick, so it was strange that this would happen, y’know? He was like: “Fuck me! What the fuck was that?” I thought: for once – because all the girls loved Mick – for once I get to be adored, instead of you.

England in those days: everything changed completely and everybody hated everything that came before. I mean, I hated flower power and those blues guys that looked at their feet while they played. So I got it. It just goes through changes.

It feels like it hasn’t changed much in the past few years.

Because everybody’s glued to the computer. I don’t know. I mean, it’s none of my business. My wife talks to this ball that’s in the kitchen. It does whatever she wants it to.

You don’t talk to it?

No, I’m not that advanced. It’s not an analogue thing. I’m too old to get into it. It’s so fast. I’m an analogue chap. Fortunately, Andy York is not. He’s totally into that kind of thing, so that helps.

Both you and Alex Harvey were Scottish or had Scottish heritage. Do you think that some of your attitude came from that?

I’ve no idea. My mum was English, my dad was Scottish. My grandma had an organ and a piano-accordion. She was a bit of a girl, my grandma. She was married a few times, she was in the Rotary and all that kind of thing. She played various instruments. She was the only one in our family that was musically inclined. Everybody else was normal. My dad was a cop, my uncle was a bus driver. Perfectly normal, apart from my grandma.

There’s a song on the album No Hard Feelings that sounds like it’s a song about a father.

Yeah, that’s a dead-on true story.

‘I’m gonna make a man out of you/If it’s the last thing I ever do.’ Those are the actual words your dad would use?

We never got on. He was a cop and I was looking for excitement. So, y’know, I would do exciting things, or my mates would, and that didn’t go down that well. I don’t know what he thought. I was a different animal. But he was a noble sort of guy. He did 25 years in the police force, he was in the war, he ended up in MI5. A very straight, noble sort of bloke. And he got lumbered with me.

My brother was okay. He was more seriously-minded. But all I seemed to want was excitement. And I went looking for that wherever it was. And some of those places, you know, my father didn’t agree with. It wasn’t easy. But at one point, I was in the shit up to my eyeballs, and he gave me 200 quid. That was a lot of money in them days.

But that 200 quid gave me six months and during that time I met Bill Farley [engineer on the first Stones and Kinks albums, among many others] at Regent Sounds in London, and that was where the auditions for Mott were held. It was Bill who rang me up and said “Come down”. So indirectly, my dad gave me that little timeframe when I needed money. He came through when it mattered. So that’s what the song’s about.

I saw you play in Milton Keynes a few years ago. Afterwards I came back to say hello and you had a load of old mates from Northampton there. It seemed like a close group of old pals.

Yeah. The thing was excitement. You couldn’t get it in those days. Regular people were not exciting and I was on this quest for excitement. I was working for British Timken [a factory that produced roller bearings for the car industry] in Northampton at the time. That was boring. Everything was boring.

And then I happened to meet a couple of naughty boys. I got introduced into the naughty boys’ society, and I was on the fringe, but it was exciting. The humour was incredible – and it wasn’t stupid humour, it was really clever. They could make a little escapade into an hour of hilarity. And all I had to do was play Danny Boy or something and I was in.

The one thing naughty boys love is rock’n’roll. The London mafia loved rock’n’roll. It was like: [dismissive] “Get your gear and fuck off” and then Freddie ‘Fingers’ Lee goes [mimics piano playing] a bit of Jerry Lee and all of a sudden we would be the life and soul of the party. Free drink, free everything. Villains always love rock’n’roll music.

What kind of villainy are we talking about?

Various types, y’know. I mean, some of these guys are still living. But they were exciting.

At the High Voltage festival in 2010, the plug was pulled too early on your set with Joe Elliott and the Down N’ Outz and it ended with a bit of a backstage brawl. Afterwards, you and Jimmy Page were laughing about it saying, “It’s just like the sixties!”

Yeah. You’ve gotta remember, it was pretty boring in the sixties. I lived in Shropshire, which is agricultural. There’s not much going on. Northampton was different. Northampton was full of life in them days.

Am I right in thinking that you had a bit of a fearsome reputation. People were quite intimidated by you, weren’t they?

I don’t know. David [Bowie] was. David thought I’d been in a motorcycle gang. And he wasn’t far off, y’know. It wasn’t a motorcycle gang, I dunno how to ride a motorbike. But David gravitated towards people he thought were a bit naughty.

Since his death, Bowie’s talked about like he was some kind of saint. But you were never close – why not?

David was a different kettle of fish. You know how people are. You go to a party, you get on with some people, you don’t get on with other people. Not because you don’t like them or they don’t like you, just because they’re accountants or they’re lawyers – they’re from a different neck of the woods than you.

David was great all the time I knew him, but he wasn’t a guy I would have hung out with. Nothing personal. We got on fine in the studio. I went out with him a couple of times, but I don’t make mates easy. I never did. And when I do make a mate, it’s for life. He was a friend like lots of people you meet along the way. David was extremely ambitious. He’d been around.

He was determined and he was ambitious. I wasn’t – I just wanted to play rock’n’roll because it excited me. But David saw a whole lot more and was going for it, 24 hours a day. He just wasn’t the type I would hang out with. But generous to a tee, lovely with the band. I mean, he gave us Dudes. I’ve got nothing but praise for David.

From the Mick Ronson angle, he seems really ruthless – the way he got rid of the Spiders – which seems like something he did throughout his career. He picked up people and then…

If you want to be that big, you’re gonna have to be ruthless. I never wanted that. The fortnight I was in the first division, it got on my nerves. I didn’t like it. First of all, you’ve got to plan years ahead, and all the rest of it. It stops becoming music, it stops becoming rock’n’roll and starts becoming business. David knew he wanted to be a monster. In a good way. When you want it that bad, you get it. If you’ve got the talent, which he did.

You're talking about the period after Dudes when you hit a purple patch and wrote All The Way From Memphis and all those classic songs. What had you learned – what changed?

It’s the press, isn’t it? It always comes down to the press [chuckles]. ‘You’re living on David Bowie,’ y’know – ‘You can’t do anything yourselves’. David wanted to do another one but it was like, ‘No way: because then we just become servants to you.’ So then of course me and Mick [Ralphs] were panic-stricken, trying to write a hit for about nine months. And it was difficult because I’m limited as a singer. Mick would write these more soulful, blues kind of things, y’know, which Paul Rodgers [Bad Company] eventually sang. He was the right kind of guy to sing Mick’s songs. I couldn’t do them. That’s the beginning of the end right there. My songs started coming through. We had to do that to get away from the David tag.

That was defiance then, too. The press said you were living in Bowie’s shadow and you were like, “Fuck you, we’ll show you”.

Still, to this day, it’s All The Young Dudes. It wasn’t even the biggest seller. The thing with Dudes was that it represented something. That’s what separated it from all the other songs. It was special. We knew that the minute we heard it. And it’s not a bad song to be tagged with either. There’s some horrible songs that people have been tagged with. It’s a great song.

Look at Jeff Beck and Hi Ho Silver Lining. He went to his death sort of hating that song.

Well, you know, at least it ain’t Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep. People say: ‘Why do you do that [Dudes] every night?’ Well, because people want to hear it every night. It’s a great song. God knows why he gave it to us. I’ve said that many times, but really, if I’d’ve had that song I wouldn’t have given it to anybody. I think we caught him just right, because he had recorded it and wasn’t happy with it. He’d done it in C, and we did it in D. Our’s was a little higher, you know, and then Phally [Verdan Allen]’s organ was great. I think [Bowie] learned a bit from the way he’d done it with his band. That’s why it came out as well as it did.

Maybe he wanted to make his name as a producer, at that time. Writing and producing a hit like that was no small thing.

Yeah. He was fabulous in the studio. He wanted to do the rest of the album, so we did. It didn’t make any sense to me. It’s like, “If you can write songs like this, get out there and do it. You’re the one with a big ambition and all that.” But somehow we had time for Iggy, he had time for Lou, you know. Pretty special.

[We talk for a bit about Mick Ralphs. Mick had a stroke in 2016. Hunter still speaks to him by phone.]

The first time I met Mick Ralphs was when you brought him to the Classic Rock Awards. I got to know him a little later. He’s a lovely guy.

Yeah, he’s a West Country kinda guy. Great humour. Short little jokes. Kept himself to himself but great to be with in a band. A beautiful player. Underplayed. Like Mike Campbell in a way – played for the song. 100 per cent. Same with Ronson. There’s two kind of guitar players: the ones that play for themselves and the ones who play for the song. I like the guys that play for the song because I’m a songwriter. Back to Bowie: I mean, that was Mick’s intro on All the Young Dudes. That’s a great intro.

Let’s talk about the seventies in rock music. There’s lots of bad behaviour. Lots of drugs, lots of booze. Did you ever feel like you were going down a slippery slope?

No. Mott wasn’t like that. The weird thing was, everyone thought they were – especially over here [in the US] – because of the name. “Mott The Hoople – what the fuck is that?” I remember San Francisco, everybody was clamouring and asking us what we were on, because they thought we were on some sophisticated British drug that they weren’t privy to. And we were on light ale.

Later on, was different, I suppose. Y’know, you have a look but it was like: “Four hours up, four hours down, that’s no good. That’s not value for money.” I really don’t see it and I really don’t recommend it to any kids coming up. Look at the opioid shit we’re in the middle of. You’ve got to be in control, you can’t let it control you. I wouldn’t advise it. It doesn’t help. You might get one song out of it, but that’s it. And the cells never forget. A friend of mine says that: the cells never forget. It always comes back to haunt you.

In Diary Of A Rock And Roll Star there’s a mention of groupies – the ladies of the hallway and so on. People are now looking back at the seventies and asking, “Were these women being exploited by bands?”

Aw, forget it. If you’re in a band with Ronson, there’s one outside the door, there’s one outside the elevator, you come out to the ground floor there’s another one there, in the breakfast room there’s two waiting for him there. These were poor downtrodden people. Some of them travelled – I mean, girls were all over the place. Not really for me. I was never that God’s-gift looking bloke. But I played with a few that were, you know. There were ladies all over the place. It was a different time, you can’t equate it with now.

But you could see how people could take advantage of them – in more than just the obvious way.

Mick would never actually bother. The thing with Mick was that he liked to pull ’em. He liked to be the best-looking bloke in the room. All the girls wanted him. On the odd occasion that they wanted somebody else, he was horrified. “What are you talking about? It’s me you’re supposed to be looking at!” Because he was so used to it.

Girls would travel, girls would be around, and some of them were really genuine: they were really into music and all the rest of it. I remember one girl travelling, and she had a two-year-old with her. And [Mott guitarist] Luther Grosvenor took her in a room and said, “You get on the bus and you go back to San Francisco where you come from because this kid should not be on the road”. And Luther gave her the money. That’s Ariel Bender for ya.

We’re in the hotel in LA and they’re sitting outside on the kerb all night. This would horrify girls nowadays, but it was how it was then. But what’re you trying to get at here, c’mon?

I’m just trying to get a sense of it. You lived through some of rock’s best years, I suppose, which in some ways are looked at now as problematic. People are looking back at, say, Steven Tyler and going: “Why did he have a teenage girlfriend? Was that appropriate?”

I don’t know. I’m not really qualified to talk about what Steve did. I know a lot of guys had pasts, you know what I mean. But that’s how life is. With everybody, not just people in rock’n’roll.

You’re on Sun Records, the same label as Elvis and Jerry Lee. How did that happen?

When I auditioned for Mott, my audition was in Regents Sound in Denmark Street. Jimi Hendrix, Little Richard – all them people – they all rehearsed or played there at some point. That was the beginning. And the American equivalent of that has got to be Sun Records in Memphis. Howlin’ Wolf, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee – I’m doing this for your readers – all these people started there. Have you been there?

Sun Studios? I have. I loved it.

I get the strangest vibe when I’m in there. It’s like a room full of ghosts. Mike said to me, “Sun Records are going to re-form. How would that feel?” And I was like, “I’ve got to be on it! The yellow label!” I’m like a fucking four-year-old. So it worked out. If these are my last two records, it’s almost like: Regents Sound. Sun Records. That’s where it all started and this is where it all ends. It’s kind of poetic in a way.

We’ll see how it goes. I’ve got Part 2 to finish, you know. But then already I’m writing for Part 3. Not because I want to, just because, y’know, you wake up in the morning and go, “That’s not bad”. We’ll see what happens. Maybe these records will do OK, maybe they’ll stiff, who knows?

How do you judge? How can you decide if something’s a success anymore?

No, it’s not at all like it was and I’m not particularly interested in how it is. So I just write what I write.

I think people are gonna love this record.

I hope they do, you know. But I don’t think I’m gonna get a lot of new people because people are into new music, you know. That’s the way they grew up. It’s the way everybody grows up. It’s what they’re used to.

You’ve gotta assume that people who are interested in Taylor Hawkins, or who like Slash or Jeff Beck, they’ll check this record out, and be interested in the connection.

It’s a very, very special record to me, put it like that. For all of them people to be nice enough to do it, and to do it as well as they’ve done it, is great in itself. It’s a lovely feeling. So if it goes no further, I’m a very happy man. Because it’s a special record.

But you earned it. Forget the classic albums: you’ve been making great records for the past 10-15 years.

I’ve enjoyed making them. The Rant Band has been great. We’ve been together 20 years now. It was time to do something different but I never realised it was gonna turn into this. It’s been fabulous. It takes a lot to make an old chap like me excited. I’m like a teenager again, y’know, with the music. All these people got me excited again.

Tell me about the song Guernica.

I was in Madrid. The gallery was down the road [Museo Reina Sofía] and I stood looking at that thing [Guernica, an anti-war mural by Pablo Picasso, prompted by the fascist bombing of the city of the same name in 1937] for about 45 minutes. It’s just symbolism, I guess. It just stayed on my mind. The weird thing was, I had a place on the south coast for a while – a place called The Beach House in Worthing. It was apartments right on the seafront, and it turns out that the Guernica survivors, the children, were all put in The Beach House. I read this recently, after I’d written the song, but there’s a connection: I lived in the same house as the survivors from Guernica.

You worked with Guy Stevens, Bernard Edwards, Roy Thomas Baker: what producer had the most influence, in terms of bringing ideas and vision to the music?

Guy. This is going back. Guy would just stand in front of you and scream at you. “You’re great! You’re better than the Stones!” And I guess it probably had an effect because we were all new to it. I’ve never really had producers. The biggest help has been three engineers and that’s Bill Price in England – he wound up at Wessex but he was at AIR when we did Mott and The Hoople – and then Bob Clearmountain in New York and the guy we’re working with now, James Fraser. He’s absolutely brilliant.

Bill Price – who produced or engineered albums by Mott, Wings, Roxy Music, Badfinger, The Clash, The Pretenders , even Guns N’ Roses – is an unsung hero of British rock, isn’t he?

Oh, people just don’t know. I mean, he did the Pistols. He got beaten up with the Pistols. There’s a pub round the corner and they went in there one night and a fight broke out and Bill was one of the guys on the receiving end. Bill was fabulous. I mean, Bill was like James – he was ahead of ya. You’d be talking about it and by the time you finish the conversation, it was there in front of you.

He would get Mick Jones [producer of Short Back ’n’ Sides, 1981] eight tracks just to fuck with. All different echoes and reverbs, because Mick was into all different sounds. He would just give him his own little sort of mixing session on the side. But he’d come in with 100 cigarettes every day. A hundred Dunhill. And smoke ’em all.

So while Guy Stevens was in your face screaming and shouting and smashing furniture, Bill was the one actually doing the technical stuff.

Roxy Music were in AIR One and we were in AIR Two. Eno and Bryan Ferry came down one night. We were doing the Mott album, and we were trying to get hold of Mike Leander [the producer and arranger who had arranged the string parts for The Beatles’ She’s Leaving Home but was better known at the time as the man responsible for that big Gary Glitter sound] or Roy from Wizzard and we weren’t having much luck. And they both said, “Well, why? You don’t need a producer. It sounds great.” And that was really because of Bill. So you know, we just carried on. And it worked. Til Ralpher left.

I read a thing where you said some songs you write are “prefabricated” – and then there’s the good stuff. I took that to mean that sometimes you feel like you’re writing clichés, or to a formula. But when it’s good, you know you’ve hit on something special. How do you know the difference?

I’m kind of on 24 hours a day. You can be watching TV and somebody says something and it kind of relates to the lyric you might be working on. I’ll think, “Yeah, I can twist that”. I have to think vocally as well because I only sound good if I’m singing a certain way. I’m not that great a vocalist. When you’re not that great a singer, you have to phrase a lot to get it across. It’s the Dylan approach, a character approach. Like, “Yeah, I could get my chops around that”. And if there’s a bit of humour there, you know, or a double entendre, I like doing that. A lot of it’s basically grammar. English grammar.

You mean enjoying words and playing with language?

Yeah. Sometimes you’re getting the point across but you’re preaching. Or it’s too serious. You try and grab something. It happens in Bed Of Roses. It happens in Angel, a couple of times, y’know: ‘I want my angels to be perfect/Except on Saturdays’ [chuckles] The track comes back [from Taylor Hawkins] with all these dead serious harmonies and all the rest of it and I’m thinking, ‘I hope nobody notices’. But it lightens it up, y’know?

Are there any of your songs that you thought would have done better than they have? For example, I think You Nearly Did Me In or Irene Wilde from All American Alien Boy are the kind of songs that could be played on radio every day of the week.

At the time Columbia Records had AM and FM acts. AM was the singles market and the FM was the album market and they felt that Mott was an FM band so they wouldn’t push any singles because that would put us into the AM market. I kept saying, “But the Rolling Stones seem to do okay in both departments”. But they wouldn’t have it. They said the same to Ten Years After. There are various reasons why things don’t happen, you know. Presidents get fired. That happened to me on Polygram. You’ve got an album coming out and all of a sudden, the President gets fired and with him all his mates.

So the new lot come in, you know, and nothing the last guy did was good. And I’ve been on little labels too. You get a song like When The World Was Round [Shrunken Heads, 2007]. It had a great video too. If it’d had a bigger label behind it, I thought that might have been a hit. And yeah, it’s a drag, because you put a lot of effort into this stuff, for very little return. That’s the song that comes to mind. I think the words are great, but what can you do? It is what it is. I was out with the Rant Band, I was having a great time and with the little labels, you don’t do much record-wise but you do a lot of merch while you’re on the road. So it works out fine.

And it’s nice for your audience. It might be small comfort, but the fact that you’ve never been a superstar has meant that your audience gets to see you in smaller venues rather than huge soulless arenas.

Yeah, I’ve always liked that. People think I’m lying to audiences when I say that. But anything between 500 and 2500 maybe, they’re amazing places to play, because you can see people and they can see you. I’m not fond of the arena shit.

I read recently that you were once asked to front The Doors. What’s the story there?

There was a guy, I forget his name, but he worked for an agency – ICM or something like that, one of the New York agencies – and I went in one day and he said, “The Doors are looking for a singer and they mentioned you, would you like to do it?” I said, “No!” [Laughs] Because Jim Morrison looked like God and I looked like an average bloke.

There’s a gig south of LA, about 60 miles down the road there, I can’t remember the name of it now, but I found out quite recently that The Doors came to one of the shows I did there. Two of them came. So maybe it was true. This was around about ‘75/’76, somewhere around there. This agency guy, he always had a gun on his desk. Which was weird, y’know.

Can you reveal anything about Defiance, Part 2?

I think it’s a bit heavier, a bit more serious. On the first one, you know, we were in the middle of Covid and Trump and all that, so I wanted it to be on the light side. The next one’s a tad heavier. As things were getting to me [laughs]. Not that heavy, just a tad more political in places. It’s supposed to be entertainment, not ramming shit down people’s necks who are already fed up.

But there’s a lot to be angry about right now, isn’t there?

That’s one of the reasons why this album is not angry. I didn’t want that. But I couldn’t help myself on the second one.

Defiance Part 1 is out now on Sun Records.