Ian McLagan: Last Orders, Please

A personal tribute to Ian McLagan, the late, great Small Faces and Faces keyboard player, and a man who brought an instant party to every barroom he ever walked into.

Meeting rock stars never gets any easier. As First World problems go, I know this reads like a doozy, but trust me: those that we worship from afar can prove to be truly terrible human beings up close. Sometimes, who cares? As a rock writer you’re there to get the story, and if the story is that your subject is an arsehole, then so be it.

That said, there are occasions when you’re about to enter the orbit of someone with whom you already share an enormous amount of emotional baggage, despite the fact you’ve never actually, physically met. You may have fallen in love to the soundtrack of their songs or adopted an entire lifestyle based on their personification of teenage rebellion. These are the people who simply cannot afford to be arseholes. This is why I’ve never been more nervous than on the day I met Ian McLagan.

Ian McLagan was part of a gang of pineapple-haired reprobates who ram-raided my blameless 11-year-old life in October ’71, spirited me away from formal education and into the arms of rock’n’roll.

As the 1970s floundered to find their feet post-Beatles, pop music was for girls and rock music for students. T.Rex were alright, but Marc Bolan wore glitter and pouted from the pages of Jackie. We pre-teen boys noncommittally scuffed our Clarks Commandos to reggae; our stars were footballers. Then Rod Stewart and The Faces appeared on Top Of The Pops and nothing was ever the same again. The song was Maggie May, the tale of a schoolboy finding love in the arms of an older woman.

The Faces were geezers. They looked like the sort of lapsed mod chancers that you looked up to on the terraces; Rod croaked like a Jack The Lad who’d shouted himself hoarse at Stamford Bridge the previous Saturday, and they all wore provocatively cut, exaggerated clothes that belonged in the driving seat of a sunset-red Ford Capri. These were the elder brothers that we all wished we had. They mimed haphazardly, smirked private jokes like naughty schoolboys and then, just as the song approached its final coda, produced a football.

As the kick-about that defined lads’ rock played out before my goggle-boxed eyeballs, my life changed forever. I was with rock’n’roll now, and I wasn’t going back. Next morning I researched The Faces. The one on the keyboards was called Ian. Inevitably then, ‘Mac’ McLagan became my favourite Face of all.

Fast forward to the end of the last century, and I’m chilling my clenched fist on a fortifying pint of Guinness in the empty bar of an anonymous home-counties hotel, somewhere in the midst of the rock-broker belt, awaiting the arrival of my erstwhile teenage idol.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In spite of the fact that he’s staying with Ronnie Wood and was up the previous night drinking Bloody Marys until seven this morning, Mac bowls through the door bang on time with a lopsided grin beaming through his Texas tan – a by-product of his relocation to Austin in 1994 – and orders us a couple of pints of ‘black madness’.

This, I immediately deduce, is a man I can do business with, and as we sit for the next four hours, guzzling back the Guinness, I’m struck by the fact that, despite having more to brag about than anyone you care to mention, Mac never once allows ego to colour his discourse. He’s funny, self-deprecating, honest, quick, charismatic, unaffected, charming, bright, witty and erudite.

In short, he’s everything you could ever want from an interviewee or, indeed, a drinking partner.

Since that first meeting, I interviewed Mac another half-a-dozen times. Almost every time he came to England, we’d meet up and I’d bask in the sunshine of his personality. Even during the worst times – following the tragic death of his wife, Kim, in a 2006 road traffic accident – he was never anything other than an absolute delight to be around.

Last time I saw him, on a sweltering day last July, we had dinner in Putney prior to him playing a gig at the Half Moon. He was as happy as Larry, full of plans and harbouring higher hopes than usual of finally reuniting Rod with The Faces in 2015. But then the fates intervened in the worst possible way.

On December 3, 2014 rock’n’roll lost one of its finest exponents. One quarter of the 60s’ ultimate mod band (the Small Faces); one fifth of the 70s’ ultimate lads’ rockers (The Faces); sideman to Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, the Everly Brothers, Bruce Springsteen, Bonnie Raitt, Joe Cocker, the Georgia Satellites, Frank Black and Lucinda Williams, and a Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame inductee who somehow managed to find the time to release eight studio albums under his own name.

So that’s what rock’n’roll lost that day… And me? I lost a pal.

Ian Patrick McLagan was born in Hounslow on May 12, 1945. His dad was a car mechanic who’d been British Roller Skating Champion in 1928, and his mum sold gloves in Derry & Toms department store on Kensington High Street. Mac always believed he inherited his love of music from his mother’s side of the family (he spent idyllic summers with his concertina-playing maternal grandmother and Uncle Ned in Mountrath, Ireland), but translating enthusiasm into whistle-able tunes didn’t always come easily. “It took me a long while to figure out musical instruments,” he admitted, as we supped in 1998.

Motivated by the arrival of skiffle, Mac took up the washboard – because it was easy. “But I had a glass washboard that wasn’t very good. My mum wouldn’t get a metal one, and thimbles on glass didn’t have the sound. And I didn’t have much rhythm, so I ended up on the tea-chest bass. I had a guitar soon after that, but it went out of tune and hurt my fingers… I had a saxophone for a while. I heard Little Richard’s horn section and thought you could play all those horn parts in one. I was really disappointed to find that it was only one note, was loud and sounded horrible.”

Which left the Hammond organ. Mac had an epiphany upon hearing Booker T & The MG’s’ Green Onions and, in 1964, trialed a Hammond L-101 on approval from a music store on Regent Street. By this point he was back on the guitar, sore fingers notwithstanding, and following much effort he’d mastered some basic Chuck Berry riffs.

“That’s all I played on the guitar, and pretty much all I play on the piano. I transposed Chuck Berry guitar riffs on to the piano. I never could figure out what [Berry’s pianist] Johnnie Johnson was playing on those Chuck Berry records. I’m playing da-da-da, like Chuck, but Johnnie’s playing what you should. And I can never play that booga-booga, Jerry Lee, all that shit, that’s fucking hard… But I’m working on it. I ain’t giving up.”

Just to clarify, at the time of making this admission, Mac had already toured with the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. And we’d both had enough Guinness to blacken the Thames.

Fondly reminiscing about his schooldays, Mac would wistfully recall: “I was a little bastard.” His discovery of the concept of ‘playing hookey’ within the pages of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn immediately transformed his schooling into a more leisurely pursuit. “I had the school record for black stars, detentions and absenteeism,” he’d proudly boast. “I used to go to Osterley Park with a sketchbook and spend hours drawing.”

After discovering he could get a grant for doing exactly the same thing at Twickenham Art School, off he went: “But I started playing hookey from there when I realised there was no money in art. Anyway, I was already in bands by then. That was my schooling.”

On the first day of his second year at Twickenham, Mac collected his £120 grant, cleared out his locker and left. “To become a professional musician,” he said. “Or, to put it another way, become unemployed.”

In August 1965, Mac’s dad shouted up the stairs of the family home: “Here, Ian. Look at this lot, will you?” ‘This lot’ were the Small Faces, performing their debut single What’cha Gonna Do About It? on Ready Steady Go! “He looks like you,” McLagan Senior concluded, pointing at bass player Ronnie Lane. By November, Mac had been headhunted by Small Faces manager Don Arden to replace the departing Jimmy Winston.

Mac thought he’d made a pretty sweet deal. Overstating his zero earnings as £20 a week, he was delighted when Arden countered with the words: “You’ll start at thirty, but be on probation for a month, then if everything goes well you’ll be on an even split with the lads.” Everything did go well, but the £20 a week never, ever went up.

The Small Faces personified the mod ideal and lived a lifestyle to match. “We were always smoking dope and taking pills,” he recalled. “The worst part was running out of dope on the road. Take it from me, it was very difficult trying to score in 1965 in fucking Barnsley.”

Having first taken acid together in early 1966 the sound of the Small Faces altered to reflect their pharmaceutical intake. The chart-topping Itchycoo Park (1967) was followed by 1968’s Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake concept piece. “But once we’d got over the rosy glow of acid it was back to soul music for us,” Mac said. “Acid didn’t change that, it was an excursion –a left turn and then back on track.”

Yet the Small Faces also managed to invent Britpop. “Lazy Sunday [Afternoon, their 1968 hit single]? Steve [Marriott] just couldn’t help himself. He always had that musichall sense of humour, and while we thought we were all blues men, we were Max Miller wearing denim.”

Mac would lubricate his tales as regularly as others would punctuate theirs. Right about now in any conversation with Mac, more drink would be called for: “We need two more pints and I’m talking about two more pints now.” And so to the bar for the usual interrogation. Wherever you went with Mac, every barmaid beyond the age of 40 would ask one of two questions: either “Is that Ian McLagan from the Small Faces?” or “Is that Ian McLagan from The Faces?” It was easy to forget just how famous he was. Especially among barmaids of a certain age…

Back at the table, pints delivered, he’d offer a quick “Sorry, what were we talking about?” before diving back into the conversation. In 1998, it was on to The Faces.

“After Steve [Marriott] left we said ‘no more lead vocalists’… Ronnie Wood came down, and then Rod started hanging around. [Drummer] Kenney [Jones] asked him in, and I thought, ‘Oh no, we don’t want another singer’. But once he started singing, I was impressed; suddenly we had a top to our pyramid. My voice is similar now, but that’s twenty-five years of smoking. Rod’s is like Bobby Womack and James Brown, and he’s never tamed it or tried to make it pure.”

The Faces’ misbehaviour on tour has since passed into legend. “We used to get very naughty. Tables and chairs would fly off balconies, because the road was so fucking boring. With twenty-two hours of waiting against two hours of playing you’re bound to get into mischief. It’s like being in the army without the war.”

After just four studio albums, a quartet of hit singles and a career that ran concurrent to Stewart enjoying solo superstardom, The Faces gradually collapsed. Sick of being sidelined, Ronnie Lane was the first to quit in 1973. Ronnie Wood jumped ship to tour with the Rolling Stones in ’75, swiftly followed by Rod himself.

So was Britt Ekland, the Swedish actress Rod started dating in ’75, The Faces’ Yoko? “No,” says Mac. “Rod was his own Yoko.” Fair enough, so that was The Faces…

As the years rolled by, Mac and I spoke over convivial libations in various locations, and the anecdotes never once slowed, let alone stopped.

There was the one where Mac kicked Ronnie Lane offstage in Cleveland; the time he had to give Steve Marriott the kiss of life after his heart stopped beating; the time he had to rescue his beloved wife Kim from her abusive first marriage to Keith Moon. Then there were tales from the road with the Stones (Keith Richards – ‘Keith Rigid’ in Mac parlance – wandering around laughing loudly with a syringe jabbed through his jeans and into his arse) and Bob Dylan (“He likes a joke, but sometimes has to be told why it’s funny”). And the revelation that Paul Weller once asked him for hairdressing tips.

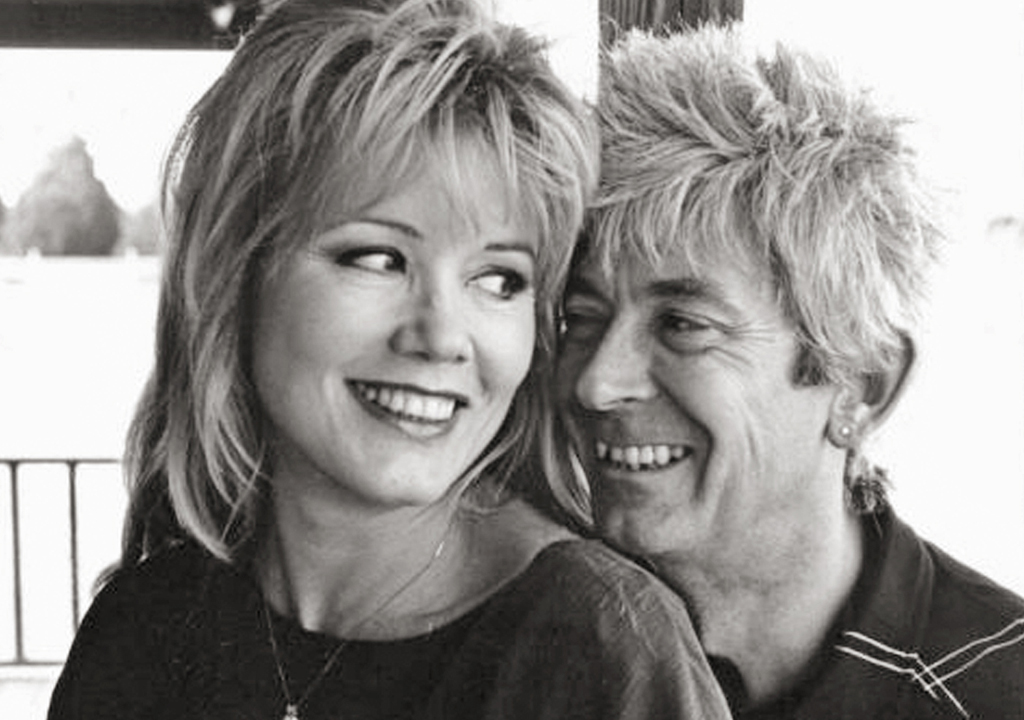

Life was always a riot with Mac, right up to the very end. We were laughing as we said goodbye for what was to be the last time. As we posed together for a photograph before I left the Half Moon, Putney, he quipped: “Look at us… the last two mods in London.”

Obviously, death – however sudden – brings with it certain clichés. “He had a good innings…”, “He’s in a better place…”. Usually it’s all so much vapid bullshit to make those that are left behind feel better. But at 69 years old, Mac, still in sprightly fettle, had played with pretty much all the greatest names in rock’n’ roll and just finished overseeing the re-release of the Small Faces’s entire recorded legacy.

The last time I interviewed him, on the phone in August 2014, I’ve never heard a man sounding quite so content and complete. When asked what in life he was most proud of, he immediately and characteristically replied: “The size of my cock.”

This, as they say, was the measure of the man. Then, following a further moment’s reflection: “My son and his daughter, my grand-daughter. She’s lovely, she’s funny, it’s a delight. We only had one day off on the last UK tour so we drove to Brighton where he lives, and we had such a beautiful day in the park there. It was just absolutely fucking perfect – the whole day.”

When I asked if he harboured any regrets, Mac replied without a moment’s hesitation.

“I don’t have any, not one. The cards are dealt, you deal with it, you move on. If you made a mistake there’s no point regretting it. You’ve learned something. All good.”

Finally, preposterously, I asked the man with the infectious laugh and the snaggle-toothed grin who, 43 years earlier, had changed my life by mischievously kicking a football about on Top Of The Pops, and who was the life and soul of the instant party he brought to every barroom he ever walked into, what would be written on his tombstone?

“I’m not going to have a tombstone. I want my ashes to be thrown into the creek on my property in Austin, because then they’ll flow down into the Texas Colorado River which flows into the Gulf Of Mexico which, thanks to the Gulf Stream, will flow to England and Ireland. My ashes will be strewn all over the beaches of the west coasts of England and Ireland. No tombstone for me, it’s over. I’m going to a better place.”

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.