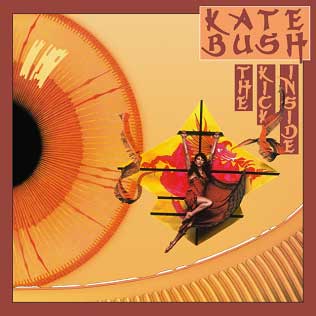

In March 1978, a young singer-songwriter called Kate Bush shot to the top of the UK singles charts with Wuthering Heights. Based on Emily Brontë’s gothic novel of the same name, it was the centrepiece of Bush’s debut album, The Kick Inside, and introduced her elegant songwriting and explosive baroque pop to the unsuspecting masses. With a little help from some early collaborators and a few famous fans, Prog charts her journey from teenage wonder to one of the most unique and influential artists of the modern age

She was the baby of the family, born in Bexleyheath in 1958, but in her elder brother John’s black and white snapshots of her aged between eight and 12, dressed up and posing in various places around the extensive family plot of East Wickham Farm and their seaside retreat near Margate, Kate Bush’s sweet little visage often shows a deep, pensive look that’s beyond her years.

Kate – then answering to Cathy – was taking everything in. Her semi-rural upbringing on the border of Kent and south-east London was a social bubble filled with family love, happily disrupted by two much older siblings who brought art, philosophy and music into an already culturally vibrant and liberal home. Their parents balanced practical jobs – their Irish mother a nurse and Essex-born father a doctor – with an enjoyment of fun and entertaining friends. While Kate’s brothers John (more frequently called Jay) and Paddy honed skills in martial arts, photography and performing folk music, Kate was surrounded by classic English poetry and literature, Celtic folklore and fairy tales, and she started to write poems. Some were published in her school magazine – a rare highlight in a time of unhappiness while at St Joseph’s Convent Grammar School, where Kate had few allies. Back home, comedy, TV drama and old films provided comfort when she wasn’t plonking away on a decrepit old church organ in one of the outbuildings, or spinning discs by Donovan, Bowie, Elton, Roxy, Billie Holiday and John Fahey.

Kate was signed up for violin lessons. However, Dr Bush – an amateur musician himself – acquired a piano and Kate’s world changed forever.

“[It was] a release,” she later told DJ Tony Myatt, “I could create something out of nothing. It was a very special discovery.”

The song compositions flowed, with lyrics inspired – as her poetry had been – by love, death and religion, among other things. By the time Kate was 13, in 1972, Jay and Paddy had recorded demos, which Jay passed to his Cambridge Uni friend Ricky Hopper, a record plugger, who shopped them around record labels, unsuccessfully. But when Ricky played the songs to his other Cambridge pal David Gilmour, who had set up a studio and was looking to foster new talent, the Pink Floyd man was impressed enough to offer his services as a mentor to the young artist: the Bush family agreed. One of Kate’s early studio encounters included sitting in at Abbey Road while Pink Floyd recorded Wish You Were Here in 1975.

“I was absolutely staggered,” she remarked in Brian Southall’s 1982 book on the studio. “I really thought I’d never be able to record [there].”

At age 15, Kate’s repertoire blossomed from 30 to 50 compositions.

Gilmour recalled to Q magazine in 1999: “I had her up to my studio and recorded some things [Passing Through Air and Maybe, with Peter Perrier and Pat Martin of Unicorn, a band he was A&Ring, on drums and bass]. I decided that the way she sang and played piano, on its own, was not going to be very effective for convincing A&R men at record companies of her value.”

He was right: these new demos were also declined at the time, and Kate continued her education – achieving 10 O-Levels and passing English, Music and Latin with particularly good grades – but pondered dropping music and entering psychiatry.

Gilmour decided to bankroll demos that would present a more 360˚ view of her music and assigned his friend, Andrew Powell, as producer-arranger.

Powell was an astute choice; a piano-playing prodigy at the age of four, he was a multi-instrumentalist and orchestral percussionist by the time he was 11 and at King’s College School in Wimbledon. Later he studied under Ligeti and Stockhausen in the 60s before joining Cambridge Uni group Henry Cow in 1968, and also the live electronic group Intermodulation, which featured composers Tim Souster and Roger Smalley. While at King’s College, Powell had put together a May Ball in that year and booked Pink Floyd – then touring A Saucerful Of Secrets – for £200; he became firm friends with the band thereafter.

After graduation Powell aimed to be a concert pianist and began performing in orchestras, but fell into session work for artists such as Nick Drake – he was mates with arranger Robert Kirby – and the jazz-rock group Come To The Edge, led by percussionist Morris Pert. Thanks to Robert Kirby he then moved into arrangements for pop music, taking on a session that Kirby hadn’t time for, Cockney Rebel’s debut, The Human Menagerie, in ’73. His treatment of the choral-enhanced seven-minute centrepiece Sebastian certainly got Powell noticed and he stayed for the next two records as he bonded with producer Alan Parsons. Powell’s blend of traditional classical rudiments and modern progressive approach – with wiggle room for theatrical quirkiness – could be just the right fit for elevating Kate’s ideas.

Speaking to Prog from his home in Wales, Powell remembers meeting Kate for the first time: “David had said to me, ‘I’ve got this girl, and at least one of her songs needs an orchestral arrangement. I can’t do that, but you can!’ I went to Floyd’s offices in Bond Street and David, Kate and I talked for a bit and then played me some of the music. I was hooked straight away. When I heard The Man With The Child In His Eyes I said, ‘I’m in!’”

And who wouldn’t be? A poignant and haunting love song in the vein of the baroque pop of the time, The Man With The Child In His Eyes was a remarkably sophisticated work in lyrics and melody by the schoolgirl. Powell noted that Kate “knew what she wanted” from production and that her compositions were “remarkably consistent”.

“We spoke about a few of her influences, and she was enthusiastic about creating a lovely orchestral part on that track in particular,” he recalls.

Alongside The Man…, Maybe and Berlin were chosen to be recorded, later renamed Humming and The Saxophone Song, respectively. Kate found herself in AIR studios in June 1975, right above the crossroads of Oxford Street and Regent Street, central London.

“It was owned by George Martin and was a studio that both David and I liked,” says Powell.

“Dave was doing his guardian angel bit… he was great, such a human, kind person – and genuine,” Kate told Q magazine in 1999. “[He] put up the money for everything. It must have cost a fortune, but he didn’t want anything out of it.”

Also working this session was Abbey Road’s eminent engineer Geoff Emerick, whose work with The Beatles, Zombies, Wings, Robin Trower and more must have been a tad daunting for Kate, but the 16-year-old took it in her stride.

“Geoff did a wonderful job on the rhythm section, and on the orchestra,” Powell says. “We did one session, I think, maybe two. I had a day between to write the orchestral parts and then we did overdubs. When we did The Man With The Child In His Eyes Kate did it in one take, and the whole recording was live.”

In July, David Gilmour took Kate’s tape to a listening session at Abbey Road with EMI’s General Manager, Bob Mercer. Mercer was impressed, but also wary of having a young, possibly vulnerable act on the books. A deal was reached – £3,000 and a four-year contract – but with the caveat that activity be held off for two years while Kate finished all her studies and gained more real-world experience. Mercer recommended Floyd manager Steve O’Rourke to the family, paid for piano lessons to refine her technique, and, importantly, took her along to a performance by Lindsay Kemp, the flamboyant choreographer and actor who had inspired and taught David Bowie.

“I just thought she might enjoy it,” Mercer said in 1999, “but she was completely blown away.”

Kemp’s world of burlesque, drag, avant-garde and erotica was another creative spur for Kate.

Kate moved out of one family home and into a flat that was one of three in a converted house in Brockley, Lewisham, owned by her parents, where her brothers also lived. With no pressure to write or record, she enjoyed this period of freedom and for a few months became part of a group, The KT Bush Band, that played local pubs and clubs. She had now fully adopted the name Kate after 18 years of being Cathy, and her bandmates were Brian Bath on guitar, Vic King on drums and Del Palmer on bass, old(ish) hands on a gigging circuit who were closer to Paddy Bush’s age – in their early-20s – and all nuts about the band Free. Already jamming pals with Brian, Paddy told him that his little sister needed a band to gain some live performance experience, so after practices at a swimming-bath boiler house in Greenwich and in a barn at the bottom of the East Wickham garden, they debuted at Lewisham’s Rose Of Lee in March 1977 with a well-drilled setlist of original Kate tunes such as James And The Cold Gun and Them Heavy People as well as covers of Motown songs, Steely Dan, The Beatles and Free’s The Stealer. By day, the 18-year-old was in jeans, T-shirts and hacking jackets; onstage at night she wore long, floaty dresses and some decoration in her hair. Nerve-wracked at first, by the time of their 20th, and final, live show, her new-found self-assurance and stage presence helped to draw audiences.

Outside of the band, Kate had enrolled in dance classes in Covent Garden led by Lindsay Kemp, mime artist Adam Darius and jazz dancer Robin Kovac. Back in her flat, in the company of kittens Zoodle and Pye, she applied herself to improving her vocals and playing her piano.

“I’d get up in the morning, practise scales at my piano, go off dancing, and then in the evening I’d come back and play the piano all night,” she told VH1, recalling the remarkably hot summer of 1976. “I had all the windows open and I used to write until four in the morning. I got a letter of complaint from a neighbour who was basically saying, ‘Shut up!’ They got up at five to do shift work and my voice carried the length of the street.”

The end of two years of development was approaching. Kate was getting impatient and visited Bob Mercer in his office with some newer songs; at some point Kate began dancing and Mercer saw her transformation.

“She now had the courage to perform in front of me like that,” he said. “I knew she was ready. Within a couple of weeks, we had her in the studios. I didn’t want to miss anything.”

Demos for the upcoming debut album occurred in locations such as De Lane Lea and De Wolfe studios in Soho, but the label had some feedback for their star David Gilmour about his charge: in their humble opinion, what was emerging was disappointing and that Gilmour had sold them “a dud”. In a 1987 radio interview he recalled that, “[Bob Mercer said,] ‘You conned us by making one song sound really good.’ I said, ‘Give me a fucking break, this girl’s really talented!’ They said, ‘We just can’t get anything right, we’ve tried God-knows-who…’ I said, ‘Why don’t you put her with the guy that I put her with originally?’… and that’s when it became plain sailing.”

Kate was finally reunited with Andrew Powell at AIR studios in July and August 1977. House engineer Jon Kelly rode shotgun on the desk and would become part of her future crew. Powell tells us that there was “no mention of budget at all” from EMI – a vote of confidence, surely. Kate asked for the KT Bush Band to be in the studio but this was overruled in favour of Powell’s dream squad of Cockney Rebel keyboardist Duncan Mackay and drummer Stuart Elliott, with Ian Bairnson on guitars and David Paton on bass, both members of Scottish pop band Pilot. Powell’s old jazz-fusion comrade Morris Pert guested on percussion, popular session pro Alan Parker on guitar and Powell dived in himself on various synths, Fender jazz bass and celeste. Lastly, Kate’s brother Paddy was present, playing mandolin and adding BVs.

Powell says that crunching a track listing down to 13 songs was “incredibly difficult” given the quality of compositions available. And then, just days before the session, Kate arrived at Powell’s flat with a new work.

“It was Wuthering Heights!” he says with a laugh. “Once I heard that I knew that it had to go on the album, so we bumped Wow off the list to make room.”

Fortunately, the players bonded with Kate immediately.

“On the first day of the session, she sat down at the piano to play them the first track,” remembers Powell. “I was watching them and thinking, ‘They’re lapping this up.’ They were mesmerised, and she was entirely in her comfort zone.”

Kate had also worked out “90 per cent of the backing vocals and other touches” while at home.

“During one track,” recalls Powell, “Stuart ceased playing and shouted, ‘Oi, stop! Listen! Can you ’ear what she’s singing? It’s really sensitive lyrics and you’re all banging away!”

It also helped that Kate would be constantly asking if any players would like some tea – they thought she was AIR’s tea girl to begin with – bringing a little of her home life sociability and maternal Irish nurturing into the space as she also picked up tips about recording and producing – as ever, taking her surroundings in.

That first track on the first day was Moving, dedicated to Lindsay Kemp, who received an acknowledgment on the sleeve, and the intro would feature a sample of a bio-acoustician Roger Payne’s 1970 popular new age record The Song Of the Humpback Whale. This might tie in with the cover art, which referenced a scene with Monstro the whale in the Disney’s Pinocchio. Kite was also recorded on day one, its reggae lilt worked up by the players in the studio.

In the final list were two “demo” tracks from the 1975 session, The Saxophone Song and The Man With The Child In His Eyes – why mess with their perfection? Bluesbreaker Alan Skidmore had provided the jazzy sax part to the former, chosen because “I wanted something slightly left-field, and I think Kate did too,” says Powell as they conjured a nightclub type of mood and realised Kate’s idea of the sax as a “feminine voice”.

James And The Cold Gun didn’t stray too far from the rocking KT Bush Band’s version, nor the treatment of Them Heavy People, the theme of which drew on Kate’s thirst for learning, and the philosophy of spiritual leader George Gurdjieff who had particularly affected Kate’s brother Jay (check out his matching moustache style) with his Eastern-influenced Fourth Way enlightenment theory.

Ever-fascinated by ghosts, ley lines and supernatural energies, the Twilight Zone-twinkling Strange Phenomena showed off Kate’s hippie side, complete with the Buddhist chant ‘om mani padme hum’. A slew of earthier songs balanced the set. Feel It, Oh To Be In Love and L’Amour Looks Something Like You were conduits for Kate’s sensual self-expression, lyrics frankly discussed with her family, much to

Ian Bairnson’s surprise when he saw her show the ‘feeling of sticky love inside’ lyric to her dad, receiving warm, supportive approval. Kate’s personal life had taken a turn; always drawn to older men, she was now dating KT Bush Band bassist Del, and they’d be together for 16 years, and collaborate creatively for even longer. Del would provide the small illustration of a man on a kite for the back cover of the LP.

The title track drew from a folk song, Lucy Wan, where an incestuous sibling relationship resulted in a pregnancy, so the sister was to take her own life to protect her brother, her final act of love. Heavy themes indeed, worn surprisingly lightly, as Powell notes: “That’s what she writes. It’s her art, it’s not personal to her.”

During the six weeks of recording, the band and technical personnel would see Kate inhabit many characters and personas, and none more so than that late addition, Wuthering Heights. Inspired by a BBC TV adaptation she’d watched in ’67, she later firmed up her lyrics with a scan of Emily Brontë’s 19th-century turbulent gothic romance, and it then developed into the tour-de-force that we know today (later, the dance moves learned from Robin Kovac would inform the weird and spooky expressive choreography for the video clip and live performances). The lyrics came from the point of view of the doomed lover Cathy, called back from the grave to haunt by her distraught and dysfunctional beau Heathcliff after her dreadful death in childbirth. What could be a better lead-off single to launch a very unusual and eccentric new artist into the world?

The label didn’t agree, pushing for the more straightforward, easier-on-the-ear James And The Cold Gun. “But Kate was very, very persistent,” says Powell. “And she was absolutely right.”

Released on January 20, 1978, Wuthering Heights and its spectral video clip made the most incredible and unlikely impression on a stunned – and in some cases bemused – general public, rising to No.1 for four weeks in March, just as The Kick Inside hit the record shops, going on to become the ninth biggest-selling album of the year. The world had never seen or heard a teenage performer like her, and now there was no going back.