When Kneecap vocalist Naoise Ó Cairealláin looks back over his band’s year, it’s not the most high-profile, headline-making flashpoints on their 2024 highlights reel which gives him the most satisfaction. It's a rather simple one.

Following the release of the west Belfast hip-hop band’s self-titled ‘heightened reality’ biopic this summer, Ó Cairealláin got a message on Instagram from a young woman he’d been friends with years previously. As a direct result, she said, of watching the Kneecap film, she had decided to enrol her child at an Irish-language primary school, even though she herself, or none of her family, spoke Gaeilge.

“We didn’t start Kneecap primarily to save the Irish language,” says Ó Cairealláin, “but obviously because we speak Irish, there’s a big part of us that wants to preserve the language, and nurture it, because the more people that speak it the better, and the longer it will survive. But that just goes to show the impact a piece of art can have on someone’s life. That child will now go to an Irish school, and learn the language, and be very cool, like us.”

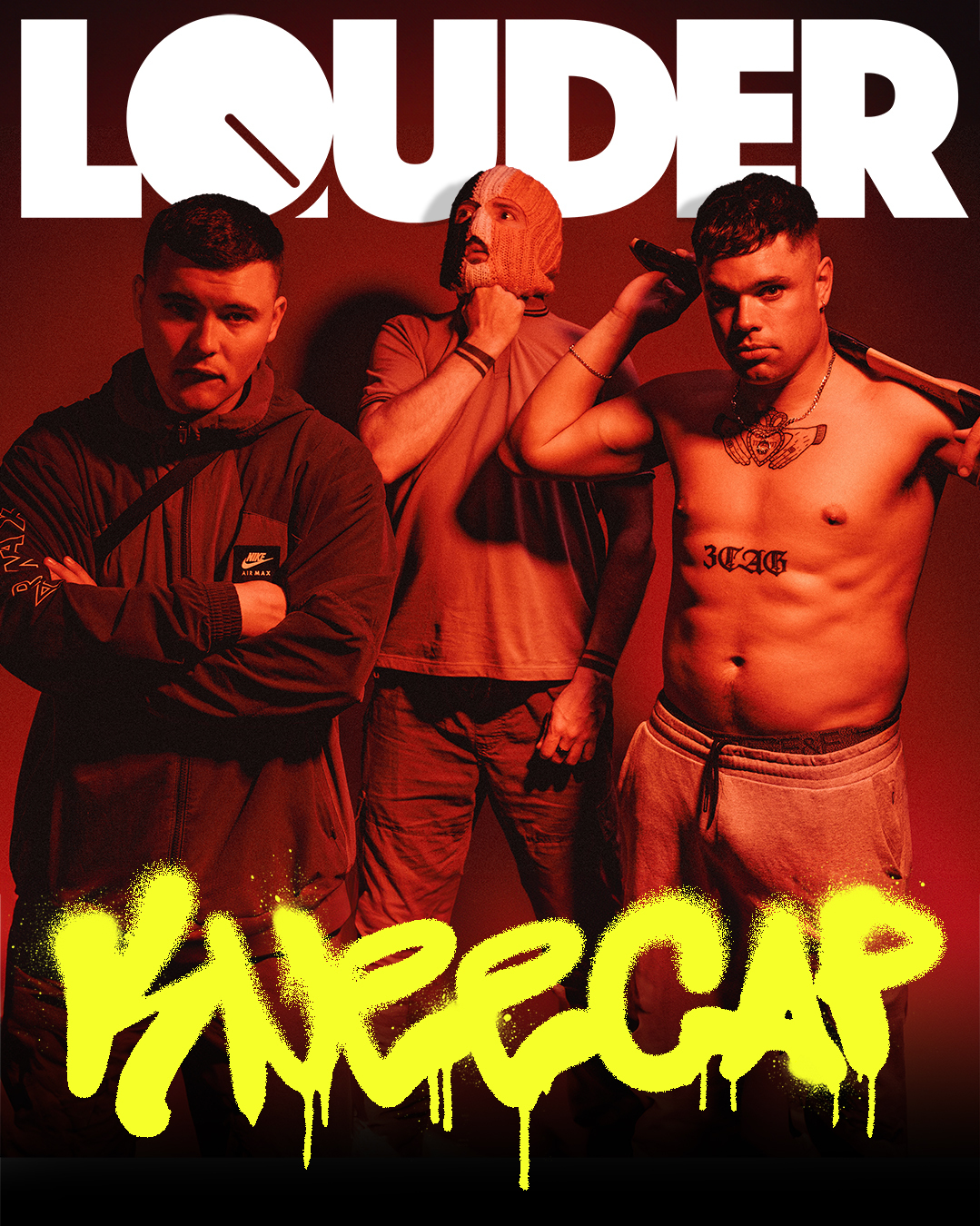

Ó Cairealláin (better known as his stage name Móglaí Bap) and his bandmates Liam Óg Ó hAnnaidh (Mo Chara) and JJ Ó Dochartaigh (DJ Próvaí) burst out laughing, but this rather sweet tale represents another small victory in what has been a truly remarkable year for the trio. Love them or hate them – and few bands are so divisive – the bi-lingual hip-hop crew are unquestionably 2024’s buzz band, lauded by superstar musicians from Elton John to Oasis bandleader Noel Gallagher, with not only that multi-award-winning biopic (Kneecap) to their name, but also a rapturously-received hit album (Fine Art) and sell-out tours of the UK, Ireland and America.

And the accolades just keep on coming. Having picked up seven awards, including the top honour, Best British Independent Film, at the British Independent Film Awards earlier this month, it was revealed this week that the trio have been shortlisted for two Academy Awards. Kneecap will represent Ireland in the International Feature Film category, while Sick In The Head, Fine Art’s second single, has been selected for the Original Song category, raising the prospect of the tracksuit-clad, Buckfast-swigging trio strolling down the red carpet at the Dolby® Theatre at Ovation Hollywood on March 2 next year.

“Oh, if we’re nominated, someone will definitely have to dig into their pockets for business class tickets to Los Angeles,” says DJ Próvaí with a laugh. “We’ll head over and get some nice goody bags. And if we win an Oscar, we’ll take it to Cash My Gold, melt it down and get some gold teeth made.”

Five years ago, Kneecap were making headlines in their native Ireland for entirely different reasons. In March 2019 Móglaí Bap, Mo Chara and DJ Próvaí were in the news after being thrown out of their own gig at University College Dublin’s Clubhouse Bar. Audience members were understandably outraged at seeing the rappers physically dragged from the stage mid-song by the venue’s bouncers, without a word of explanation: only later did student union officials reveal that they considered the band’s performance of single-in-waiting Get Your Brits Out – a hilariously over-the-top fantasy about taking politicians from the notoriously uptight Democratic Unionist Party out on the lash – to be in contravention of the college’s Dignity and Respect policies.

“The bouncers lifted us like surfboards and forcibly escorted us out of the building,” recalls DJ Próvaí. “Things have changed a bit since then: we haven’t been thrown out of our own gigs for a few years. I don’t know if that means we’re doing something right now or doing something wrong.”

“Things have changed a bit since then” is a fabulous piece of understatement from the former school teacher from Derry. Consider this: at the end of October, the trio were back in Dublin to play five sold-out shows at the city’s 1,500-capacity Vicar Street venue. And this time, rather than being “fucked off the stage” by pissed-off bouncers, they had Ed Sheeran, one of the world’s biggest pop stars, knocking on their dressing room door, wanting to hang out.

“Ed’s great craic,” Próvaí says. “Loves an aul dirty joke. For someone at his level of stardom, he comes across as very grounded: he walked in, swigged some Buckfast and Beamish with us, and we hit it off straight away. He’s a sound cunt.”

“Oh, and Robbie Williams has invited us to come see his new film [Better Man, set for release on December 25],” he adds casually. “He saw our film and loved it, and got in touch. He wants to come along to a show.”

There’s a brief pause while Próvaí lets this sink in.

“Aye, it’s been a mad, surreal, brilliant year,” he reflects.

“No revolutionary movement is complete without its poetical expression. If such a movement has caught hold of the imagination of the masses they will seek a vent in song for the aspirations, the fears and the hopes, the loves and the hatreds engendered by the struggle.”

With these words, in 1907, revolutionary socialist, trade union leader and Irish republican icon James Connolly introduced Songs Of Freedom By Irish Authors, a songbook of stirring rebel anthems to fire the spirits of Irish men and woman united by dreams of rising up against establishment rule. The songs on Fine Art might not always concern themselves with heroic deeds and actions – there are significantly fewer words in praise of the transportive powers of cocaine and ketamine in Connolly’s songs – but in 2024 the Republican trio have kickstarted a genuine revolution of their own, whether raising awareness of the ongoing fight for a united Ireland, raising funds for those affected by the ongoing genocide in Gaza, or highlighting the need for respect and tolerance for refugees in the North of Ireland in the wake of racist riots in Belfast.

Kneecap began the year as they meant to continue: causing chaos. Ahead of their biopic, written and directed by Rich Peppiatt, becoming the first Irish language film to premiere at the prestigious Sundance Film Festival in Utah, the trio commandeered a Police Service Northern Ireland Land Rover, and pulled up outside Park City’s Egyptian Theatre on January 18 holding smoking green, white, and orange flares, to the bemusement of both bystanders and the local police.

Later, during a Q&A session staged after the screening, Móglaí Bap had his own question for those assembled, asking “Does anybody have any drugs?”

“Cheap”, Mo Chara emphasised.

By the time the festival concluded, Kneecap had walked away with the Audience Award, sold worldwide distribution rights for their film, and saw first-hand that speaking and rapping in Gaeilge presented no barriers to their story connecting.

“The audience were laughing at completely different beats,” says Móglaí Bap. “They loved it in a completely different way from someone watching in Belfast, but it was class to see that even if they didn’t know what the fuck we were saying at times, they were laughing all the same.”

“The impact it’s had has been amazing. Our whole tour in America was sold out, and everyone at every gig had seen the movie.”

“And there’s Irish language classes springing up in every city and state now,” adds Próvaí. “They’re all speaking Irish with American accents.”

Not everyone received the film in such a positive manner, however. No sooner had news of the band’s triumph in Utah broken, than British newspapers were running articles amplifying criticism of the film by Conservative Party and Democratic Unionist Party MPs, focusing on the fact that it received funding to the tune of £760,000 from Northern Ireland Screen, and a further £775,000 from the National Lottery, via the British Film Institute. Former Northern Ireland Secretary Theresa Villiers professed to be “shocked” at this “unjustified use of public and lottery money” and accused the band of “promoting division”, while DUP MP Gregory Campbell dismissed Kneecap as “ultimately little more than an offensive three-piece version of (Irish X Factor contestants) Jedward”, an uncharacteristically amusing putdown, to be fair.

It’s easy to imagine that Kemi Badenoch, the UK’s Business and Trade Secretary, had such criticisms in mind in February when she stepped in to personally veto a £14,250 grant awarded to Kneecap by the Music Export Growth Scheme to help fund their first American tourism, based purely on the fact that the trio hold Republican beliefs and wish to see Ireland reunited. “We fully support freedom of speech,” Badenoch told The Irish Times newspaper, “but it’s hardly surprising that we don’t want to hand out UK taxpayers’ money to people that oppose the United Kingdom itself.”

Her ill-advised intervention would hand Kneecap the kind of worldwide PR boost that no amount of money could buy. Fast forward to November 29, and following a ruling that Badenoch, now the Conservative Party leader, acted illegally in blocking the arts grant to which the trio were fully entitled, DJ Próvaí stood outside a court in Belfast to reveal that the £14,250 awarded to the band would be split equally between two organisations working with Catholic and Protestant youth in Belfast, and to tell the gathered journalists why Kneecap’s legal victory matters.

“They don’t like that we oppose British rule, that we don’t believe that England serves anyone in Ireland and the working classes on both sides of the community deserve better; deserve funding, deserve appropriate mental health services, deserve to celebrate music and art and deserve the freedom to express our culture,” he stated. “They broke their own laws in trying to silence Kneecap.”

It’s entirely possible to appreciate and enjoy Kneecap’s music without any knowledge whatsoever of where the band come from, but to truly understand their humour, their activism, their politics, and the foundations of their art, a basic understanding of the troubled history of the North of Ireland helps.

Though the opening minutes of Kneecap, the movie, makes it clear that the group’s origins are not rooted in ‘The Troubles’ – the complex, bitter political, social, civil and religious conflict which resulted in over 3,500 deaths and impacted life in the Six Counties and beyond from 1969 through to the signing of the Belfast Agreement in April 1998 – a significant part of their art is rooted in black-humoured deconstructions of sacred cows and sectarian tropes, which previous generations were often loathe to address amid a climate of fear and intimidation.

This is one of the reasons that Elton John professes to love the band. “Your music tackles controversial subjects, and you say that unless you make a topic of it, and make fun of it, it’s never going to get any better,” he noted during a September interview with the band on his Apple Music show. “I think you’re very brave to do that, you’re very brave to speak out.”

A photo posted on the band’s Instagram account in July, is the perfect example of this. Beneath the caption ‘Cross-community relations at Madrid Airport’ the trio are shown arm-in-arm with a young man from Belfast, who’s wearing a full Rangers Football Club kit, signifying his Protestant background. In the comments section, the man in question wrote, “Ah ffs lads… that’s me getting shot when I get home’, following by two laughing face emojis.

“Fair play to that guy, he totally got the craic,” says Móglaí Bap. “We started slagging him because he’d a full Rangers kit but an Irish passport, and it’s that kind of banter which takes the sting and bitterness out of our differences.”

Not everyone gets it, of course. While Oasis’ Noel Gallagher was hugely impressed by Kneecap’s performances at Glastonbury festival this summer, his younger brother Liam is not a fan. During one of his regular spontaneous Q&A sessions with his followers on The Platform Formerly Known as Twitter, it was suggested to Gallagher Jnr. that Kneecap could be the perfect band to support Oasis on tour next year. “Not happening,” he replied. “There [sic] a bunch of squares in knitted face thongs.” When another X user posted a photo of Noel Gallagher backstage at Glastonbury with the band, Liam responded, with his usual disdain for grammar, “That’s him not me I don’t do politics we’re here to come together not to divide.”

“He’s not wrong about the thongs,” laughs Mo Chara, before adding the hilariously childish joke, “They’re his ma’s thongs.”

“Liam is just jealous that Noel met us first,” he says. “Noel is sound as fuck.”

“Liam was in the green room too, but we had to fuck him out as he had a face on him,” adds Próvaí. “He was raging.”

Is that actually true or have you just made that up?

“It’s bollocks,” says Próvaí, with a wink, “but sure print it anyway.”

In truth, Kneecap are going to be way too busy next year to need to hitch a ride on the Oasis bandwagon, or anyone else’s. The’ve a sold-out tour of Australia and New Zealand in March, a first festival headline slot at London’s Wide Awake festival in May, a sold-out, 11,000 capacity Dublin show in June, and another festival headliner at 2000 Trees in July, plus more shows lined-up in the US and mainland Europe. There’s also the important matter of writing the follow-up to Fine Art, a process, they say, is already well underway. Anyone worried that the trio’s newly-elevated profile will see them abandoning their working class roots can rest easy.

“We’ll always be low-life scum,” says Próvaí, echoing the chorus of live favourite H.O.O.D. “We haven’t become middle class, we still stand for working class people. But maybe when the money rolls in next year we’ll buy a wee castle and get all our scum friends in for a party.” [Laughs]

“But no, the second album is already in the works, and we’re working with [Fine Art producer] Toddla T again. We’re busy, but it’d be stupid of us to complain about that when we’re doing the job that we’ve always wanted to do. It’s a blessing, and we keep reminding ourselves about that. We’re working towards better lives for our families and our friends, and we’re thrilled that this is our life now.

"Our friends in West Belfast and the Creggan are very good at grounding us, and there’s no chance of us getting above our station.”

Fine Art is available now via Heavenly Recordings. Kneecap (film) is available to stream now via Apple TV, Amazon Prime and more