Factually, Talk Talk were an Eighties band. They effectively existed from 1981 to 1992. Yet it’s hard now to think of music which sounds less typically Eighties than theirs. Sure, the early albums were period synth-pop, complete with fretless bass, shepherded by the record company towards the New Wave-New Romantic overlap which the likes of Duran Duran (early label-mates and touring companions) gobbled up.

Yet Talk Talk had travelled so far by the climax of their trajectory that their later work, the work for which they are remembered and loved, sounded completely separate from such notions as time and space. They tapped into something eternal, profound, transcendent. They probably invented post-rock, but are unique and indefinable. Whispered and wailed confessions, psalms and exhortations spring from their depths, that voice more gospel than pop, the broken-up then rebuilt musical structures aware of the codes of jazz, progressive rock and soul but emanating from what might be a blinding light in a subterranean cave.

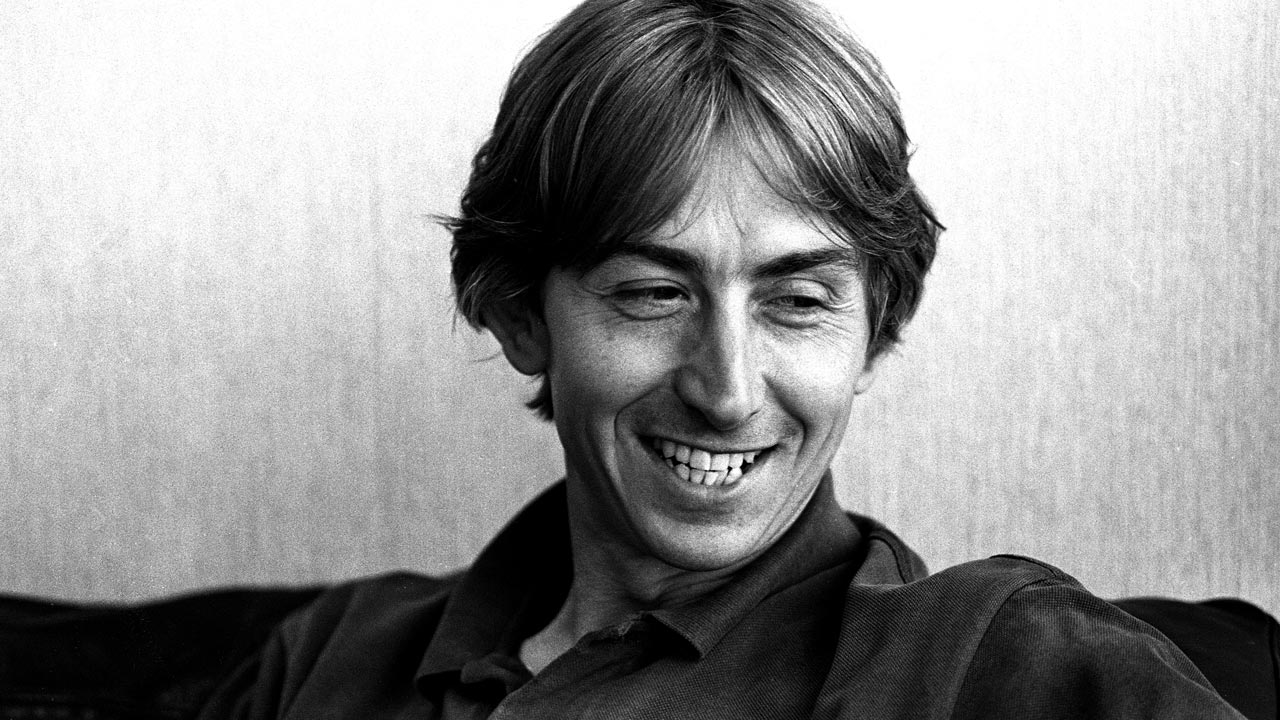

The death of Mark Hollis at age 64 has put an end to the understandable hopes of many that he, or Talk Talk, might reappear one day with further new music. In reality this was never likely to happen. Hollis all but retired from music after his one solo album in 1998, and seems to have decided to happily focus on family life, turning his back on an industry with which he was patently uncomfortable.

It’s too easy to label a musician a “recluse” just because they haven’t been releasing albums and doing interviews: one interesting thread over the last 24 hours has revealed that he was a keen motorcycle enthusiast. A fellow member of that informal club has said that, upon realising who Hollis was, he gushed that he wanted his music played at his funeral one day. Hollis laughed, benignly. He’d moved on. It must have seemed to him like a memory from youth, living in another world.

And while more of his music would, for us, have been at best inspiring, at worst intriguing, there is a kind of beauty in achieving perfection in what you set out to do then leaving it there, having said what you wanted to say. He’d advocated the spaces between, the silences, the parts you leave out. As he, never good at the promo game in an era where it was vital, told one interviewer, “If you understand it, you do. If you don’t, nothing I say will make you understand it. The only thing I can do by talking about it is detract from it. I can’t add anything. Can I go home now?” For the last 21 years, he went home, his masterpieces done.

Few saw this greatness growing as Talk Talk appeared, dressed like lads who’d studied Roxy Music’s latter-day wardrobe too closely, on their 1982 debut The Party’s Over. Perhaps the title had more resonance than was at first noted. Not that it was poor: of-their-era hits like Today and Talk Talk still motor and shine. Something in Hollis’ keening voice already suggested he had more sorrow and joy to express. As peacocks however, they were gauche. “We just got caught up in a whirlwind”, he sighed.

In October 1982 they supported Genesis at their Six Of The Best reunion show with Peter Gabriel at Milton Keynes Bowl. The weather was atrocious. It did not go well. By 1984’s It’s My Life they were in bed with dancefloor-remix culture, even though songs like Dum Dum Girl and Such A Shame were riddled with melancholy. Talk Talk’s only possible parallel might be Japan, who similarly moved from (partly imposed) foppery and frippery to brittle, brutally candid angst.

It was 1986’s The Colour Of Spring on which the doors of the cage were flung open, and all kinds of odd animals, birds and insects – echoed by James Marsh’s classic cover art – tumbled out. Life’s What You Make It and Living In Another World pulled off implausibly brilliant marriages of euphoric big beat and eccentric, left-handed shifts. Between these bold lines, flickers of their music’s future murmured through on fragile, floating elegies like April 5th and Chameleon Day.

The Colour Of Spring went gold, so EMI had no problem backing Talk Talk with a budget. They weren’t at all convinced this had been wisely spent when 1988’s landmark Spirit Of Eden revealed itself. Famously, Hollis and co-writer/producer Tim Friese-Greene were imposing almost evangelically bizarre studio routines (or anti-routines), and the results were a radical, neo-religious fusion of gospel, classical and prog tropes.

The Rainbow, Eden, and I Believe In You stand as musical edifices which cause your jaw to hit the floor while your soul is showered in exaltation. Even now – and it’d be a hard-hearted Talk Talk fan who played them today without experiencing something in their eye – the album teases out new treasures with each listen. (Contrary to myth, it wasn’t universally panned by critics. Reviews ranged from glowing to ghastly).

Now understood as an artist who didn’t compromise, Hollis (having switched labels) re-engaged for the swansong under the Talk Talk name, 1991’s archly-titled Laughing Stock. If Spirit Of Eden created post-rock, this created post-post-rock. Sparse yet studded with intensity, it drew a new map: “Trust us, listener, drop your compass”, it said, “and these seemingly random shapes will eventually coalesce into something quite magical”. Minimalism was now appealing to Hollis, and after the (by then notional) band’s split, his self-titled 1998 solo album was brittle and breathtaking. That year he came close to describing his ethos: “Before you play two notes, learn how to play one. And don’t play one unless you’ve got a reason to play it.”

He took his own advice, embracing silence. Everything he struggled to communicate verbally was there, IS there, in the music. Happiness, desire, floods, belief. An “ordinary”, Tottenham-born football fan whose brother Ed had managed Eddie & The Hot Rods, he packed it all in because “I choose my family”. The family of musicians remains forever in awe of his work. In a very early interview for Look-In magazine he chose his ten favourite records: these included Marvin Gaye, Augustus Pablo, Walter Carlos, Keith Jarrett, Faure and Shostakovich. He was never going to be your average pop star.

The word “genius” is bandied around too readily. In this case, immersion in those last three Talk Talk albums insists it’s entirely appropriate regarding Mark Hollis. That music, stroking and scratching the sublime, is deathless.

Chris Roberts is the co-author of Spirit Of Talk Talk (Rocket 88 Books)