He is perhaps most widely known as the drummer with Traffic, the band he co-founded in 1967, and thus for his crucial role in one of experimental rock’s prime exponents. But the switchback muse of the late Jim Capaldi took him to so many addresses and incarnations, that the recent digital release of one of his solo landmarks is the perfect time for an identity check.

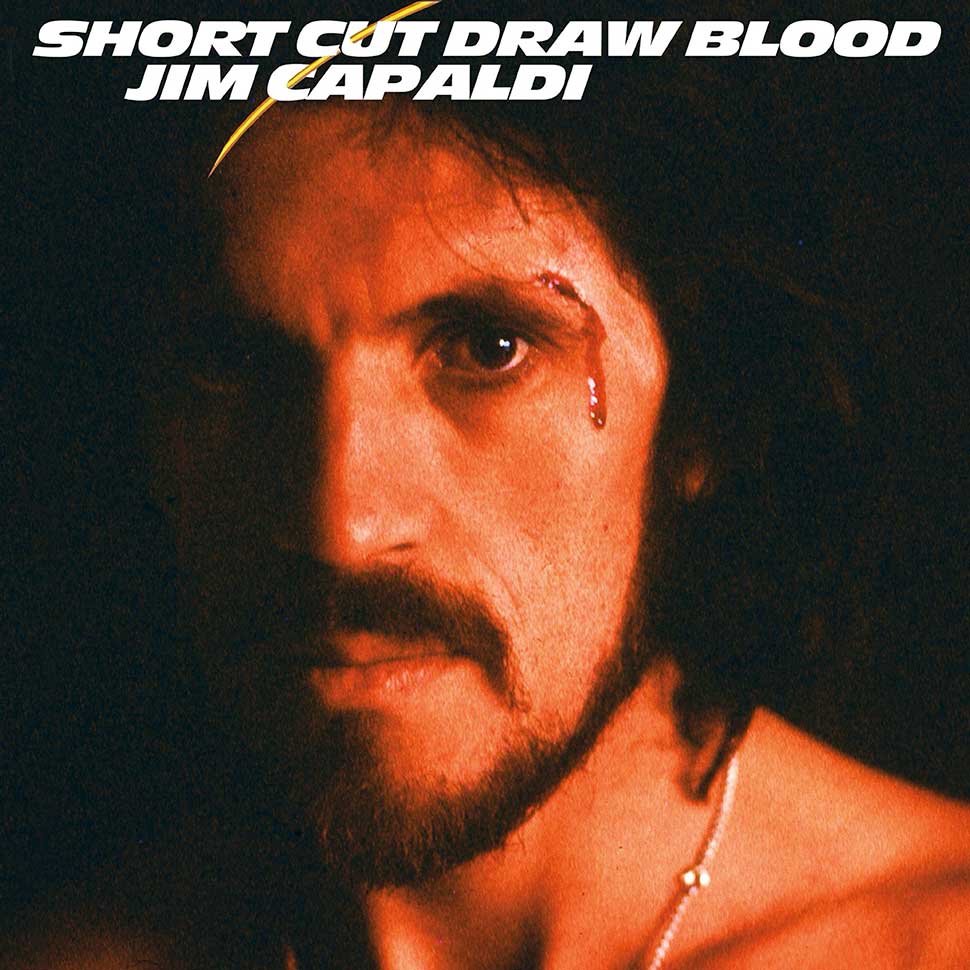

Earlier this year, Island Records gave a long-awaited online debut to one of the landmarks of Capaldi’s catalogue of a dozen-plus albums in his own name, 1975’s Short Cut Draw Blood. To existing admirers, the record is a returning friend, to newcomers it’s a window into a career that has become a little too easy to underrate. Six new deluxe heavyweight vinyl reissues, available individually from 2019’s Traffic – The Studio Albums 1967-74 box set, further correct the imbalance.

From loyal band man to solo hitmaker and philanthropist, from cherished friend and collaborator of the Winwoods, Claptons and Harrisons to award-winning songwriter, Jim Capaldi was a man of many roles. He starred in many of them, but that was never the point. Music itself sustained him, all the way until his sadly premature death at the age of 60, in 2005.

A measure of the love and respect that Capaldi engendered from his peers came in the line-up for the 2007 tribute concert Dear Mr. Fantasy, at London’s Roundhouse. Gathering to pay, and play, their respects were Pete Townshend, Paul Weller, Jon Lord, Cat Stevens, Gary Moore and of course Steve Winwood, among many others.

Short Cut Draw Blood is a splendid musical timepiece, and an admirable place for anyone to start their appreciation of a proud West Midlander who travelled the world. Recorded after the conclusion of Traffic’s initial history, it featured other former members of that venerated band in Rebop Kwaku Baah and, of course, Winwood, along with guest appearances by Paul Kossoff, Chris Spedding, Jess Roden and John ‘Rabbitt’ Bundrick.

The album, like so much of Capaldi’s catalogue, comfortably switched from pop to rock to jazz and reggae flavours, stopping off for a couple of hit singles along the way: a minor one in the gentle It’s All Up To You, and a big success with a cover of the deathless Love Hurts, which was in the UK top five at the same time as Bohemian Rhapsody.

For a man raised on the glorious 45s of the pre-Beatles American pop of Roy Orbison, whose version he adored, it was an unexpected pleasure. It was listening to that album again that caused me to muse on how many times Capaldi had been part of not just my musical education, but also my working life.

I interviewed him in person twice, firstly following the release of his 1988 album Some Come Running, then with Winwood when they reunited under the Traffic name for 1994’s Far From Home and the ensuing tour.

I also handed him the awful task of eulogising his friend George Harrison for a national newspaper piece I wrote when Harrison passed away in 2001. Then, with sad symmetry less than four years later, it fell on me to write an obituary of Capaldi himself for Billboard magazine. In both cases it felt painfully too soon to be doing so.

The digitisation of Short Cut Draw Blood has done us a collective favour in shining renewed light on an important musician, not to mention a humanitarian whose perceptive lyrics about the woes of the planet now sound alarmingly prescient. It’s a record that underlines the versatility of an artist who could rock as hard as the next person, but also inhabit the sensitive songwriting territory of a Justin Hayward or even a Carole King.

We now have the benefit of a new tribute to him from Steve Winwood, exclusive to this story, in which he reveals that but for Capaldi’s demise, Traffic would have reunited again.

“Jim was one of my greatest friends and he was my writing collaborator well into the nineties, twenty or more years after the break-up of Traffic,” says Winwood. “He had boundless enthusiasm and an almost child-like zest for life, and an uncanny ability to charm everyone he met.

“Our writing methods were unorthodox in many ways. And we must remember that Jim was a great drummer, also unorthodox, so it was inevitable that rhythm and drumming would be part of the writing process. To say that our writings came from ‘jams’ is correct to a degree, but it must be remembered that all composition stems from improvisation. When writing songs, Jim would have written some lyrics before we set about improvising music, then when it felt right I would begin singing Jim’s words.

“Traffic disbanded in the mid-seventies, I think because of a certain disillusionment with the music scene as a whole,” Winwood continues. “Punk rock was emerging and we probably felt we no longer fitted in. Of course, as time went on we realised that Traffic did indeed have a place in British music history, and this was manifest in the re-formation of Traffic in 1993. We had planned to go out as Traffic again, and would have done were it not for Jim’s untimely passing.

“On Short Cut Draw Blood I didn’t collaborate with Jim on the writing. My role was as a musician on some of the sessions and a kind of production input. I know that Jim had his own music ideas, and I suspect that his solo albums were a vehicle for his own music, as on Traffic records he was confined to writing the lyrics and playing drums and percussion.

“Jim and I used to make time together to get inspiration from all walks of life,” Winwood muses. “We spent many happy hours roaming the countryside, mainly England, and sometimes Wales, often to historic sites, and making random acquaintances. I still miss him very much. Short Cut Draw Blood is a fitting legacy and a tribute to a great man.”

Nicola James Capaldi was born a war baby to Italian parents in Evesham, Worcestershire, on August 2, 1944. His father Nicholas was a music teacher, which gave the young man a head start at the piano and in vocal technique. Playing drums followed in his teens, as did his formation of The Sapphires, who gigged locally. But rock’n’roll was no place for a guaranteed career in those days – if indeed it ever has been.

At 16 Capaldi took up an apprenticeship, where he met Dave Mason, who later joined him in The Hellions. They served time (the phrase is chosen deliberately to reflect the glamour-free grind of the posting) at the fabled Star Club in Hamburg, backing singer Tanya Day. There they met the nascent Spencer Davis Group, and Capaldi’s lifelong friendship with their singer and keyboard player Steve Winwood began.

The Hellions released three singles, including the Buddy-Holly-meets-beat-group A Little Lovin’, but chart compilers were untroubled by them. Nevertheless, the group’s early move into writing originals continued into later incarnations as The Revolution (without Mason) and Deep Feeling. Rock was getting louder, and so did they, as they played around the Midlands, including with an as-yet unrecognised Jimi Hendrix.

Winwood had, of course, been the teenage sensation and lead voice of the Spencer Davis Group’s spectacular national and international success, from 1965 to 1967. But the pop merry-go-round was not for him. Soon he joined Capaldi, guitarist/vocalist Mason and another Brummie, saxophone and flute-player Chris Wood, in Traffic.

Traffic’s fascinating transition from short-lived psychedelic popsters to enduring progressive pathfinders could fill an issue of Classic Rock on its own, and it was a source of pride to Capaldi.

“It was never ‘Next hit off the album,’ we were living what we did,” he told me in 1989. “It just came right out of what we felt, not what was expected or what could be marketed.”

At the encouragement of Island Records founder and their first producer, Chris Blackwell, Traffic famously ‘got it together in the country’ in their Berkshire cottage at Aston Tirrold, where their music became as free-spirited as their catholic lifestyle. But soon, success demanded live work, with consequences that swiftly told on them.

In Record Mirror in December 1967, David Griffiths wrote: “A few days ago I had a brief conversation with Jim Capaldi and asked how Traffic were making out in the Harsh, Real, Touring, Pop-Concert World. ‘We’re feeling the pull a bit now,’ he confessed. ‘It gets on your nerves – all this chasing around here, there and everywhere. But since the group’s career has gone so fantastically well – better than we dared hope – we reckon it’s all been worth it.’”

In his memoir Do You Feel Like I Do?, contemporary Peter Frampton captured the moment in pop history when he, even pre-‘Face Of 1968’, was out with The Herd on a package tour. And get this line-up: The Herd were on in the first half, after Marmalade and before Traffic. The second half of the show was The Tremeloes and headliners The Who.

“It was all exciting to me,” wrote Frampton. “I’m walking past an open dressing room and there’s Stevie Winwood and Jim Capaldi from Traffic sitting there, and their room always smelt pretty heavy.”

Once Traffic had shaken off the pop market, and were at least more free to pursue the eclectic spontaneity that made them unique, their glorious album years followed. In our 1989 interview, Capaldi listed some of their work that he was most proud of. “The early track would be Dear Mr. Fantasy, and then the later track towards the end of Traffic was The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys.

Musically, if you listen to those two things, there’s not many bands that would span that variation. “Low Spark was never written to get played on the radio. It just came right out of what we felt, purely, and only what we felt. When you hear a piece of music like that, it’s like: ‘Wow, this is coming from somewhere else.’”

Were there things you would have changed about Traffic’s halcyon years?

“No, not at all. I think it was perfect. It happened the way it happened. Nothing got over-produced or over-thought about, and it stands up because of that. It’s got integrity.”

Capaldi’s early solo years weaved in and out of his work with the later Traffic line-up’s stop-start activity, beginning with 1972’s Oh How We Danced. Co-produced with Chris Blackwell, it included the charming piano ballad and single Eve, with Winwood playing organ. Winwood and Capaldi would continue to contribute to each other’s records, as good friends do.

Capaldi took the helm on his own for the 1974 follow-up Whale Meat Again (good rockers loved bad puns). Both albums found a wider audience in the US than at home, benefiting no end from the existence of an entire broadcast genre that we simply didn’t have in the UK: album rock radio, with the occasional flip over to the AM dial for a spinoff 45.

Speaking of which, when Short Cut Draw Blood was released, Capaldi’s reworking of the much-covered Love Hurts was hugely successful, especially in the UK where it reached No.4.

“I loved the song,” said Capaldi. “It was Roy Orbison’s version that I had, on an old album of his. He was one of my all-time favourites. I hadn’t quite intended for it to come out the way it did, that was kind of accidental in the studio. I said let’s try and give it a bit more of an up-tempo [feel], everyone that’s ever done it has done it in the original slow feel. So it turned into I guess a pop record, but still with some good qualities, because of the playing on it – Jean Roussel [on electric piano and Minimoog], and Steve played keyboards as well. And it was a very big hit in England.”

That love of Orbison was typical of Capaldi’s broad palette. “I was playing Otis Redding the other night,” he told me. “That’s got to be one of the greatest voices ever. It’s just a case of people being drawn back into a little bit more depth in the music, into something to be said. Because it did get very much like light entertainment for a while, it became a great big ‘sell’, a big hype.”

By now, Traffic had ground to a standstill, hamstrung by exhaustion and ill health. The name was mothballed for nearly 20 years. In the later 70s, Capaldi dabbled (largely unhappily) in disco, but soon returned to his strengths, living with his Brazilian wife Aninha between Rio and their English home in Marlow.

“I wrote a few songs which were about Brazil, and I did a couple of songs that were Brazilian and I put English lyrics to them. So that interaction came out, but I didn’t suddenly come out with an album with samba all over it. I’ve always written things with a basic Latin rhythmic feel. I like that feel. In Traffic we always had congas on stage, and I’ve always listened to a lot of Latin music, so it’s quite close to home.”

The 1988 album Some Come Running brought a new injection of energy to Capaldi’s career, as evidenced by our interview of the time in which he enthused about guest spots by Steve Winwood, George Harrison and Eric Clapton.

“Every track stands up on its own,” he said proudly. “I wanted to make an album that showcased me and the production, something you could listen to.”

A later session, for the track Oh Lord, Why Lord, took place at Harrison’s house. The pair had met occasionally in the 60s, but had become much closer friends in later years.

“He lives eight miles down the road from me, and he very kindly gave me a couple of days,” Capaldi explained of the session. “I took the tapes up, and he was great. We sat there and jammed out some old Beatles songs, very relaxed, and he played most of the rhythm arpeggio and slide parts.

“[George] played over the end of the song but he was never very comfortable, because he plays a more simple approach, he doesn’t actually solo as such, as a virtuoso. So he said: ‘Well, I’d get Eric, that’s what I do, to play the fast stuff.’ I happened to be on a charity walk with some people, including Ian Botham. Eric came out and the timing just seemed to fall into place.

“I said ‘You owe me one’ – I played for him on the Rainbow [Theatre in London] concert in ’73, when he made his comeback gig. I said: ‘Do you fancy doing something for me,’ and he said great, he just popped in.”

Harrison, along with Winwood, Paul Weller, Gary Moore and Ian Paice, was also on Living On The Outside, Capaldi’s eleventh solo album, released in 2001, soon before we lost George to cancer.

“It was just an honour to have done stuff with him,” said Capaldi. “Everybody who worked with him would say the same thing, because The Beatles meant so much to me and everybody else.

“He had a great sense of humour, that’s one of the things I’m going to miss the most,” he reflected about his friend. “We used to have a very silly sense of humour and play some great word games. I’m grateful to him for introducing me to transcendental meditation. As he said in many statements, it’s the inward journey – dealing with who you are and where you’re going. I know he had a fantastic amount of strength.”

In the early 90s, there was a palpable sense that the tide had turned back towards the progressive folk rock that Traffic had symbolised. Weller, then setting off down his own genre-blending solo path, was one of many to cite them as an influence.

Winwood – by this time a chart-topping, Grammy-winning solo star – and Capaldi reconvened under the Traffic name for 1994’s Far From Home album and a subsequent major tour. Covering a double-headliner date with the Steve Miller Band on the North American leg that summer, in New York state, I sat with the two of them on their tour bus.

“Punk rock was down on Traffic’s kind of thing, because punk was a very a musical form,” Winwood mused. “But oddly enough, people like Paul Weller came out of punk rock. I don’t claim to understand it, but fashions do go round and round.”

To which Capaldi added pugnaciously: “Just because a certain music was alive twenty years ago, it doesn’t mean it has to be nostalgia now, it can still be good music. The culture of rock’n’roll is very instantaneous, something that’s here today, gone tomorrow. But I think Traffic has always been more of a music band than rock’n’roll.”

Capaldi had the satisfaction of further endorsement for his skills as a soft-rock songwriter in 1996. Love Will Keep Us Alive, which he co-wrote with Paul Carrack and Peter Vale, won the prestigious ASCAP Award as Song Of The Year after it was snapped up and delivered to millions by the Eagles, on their Hell Freezes Over reunion tour and subsequent live album.

Back in ’89, that tough exterior was failing to conceal boyish enthusiasm, especially when I asked Capaldi about his second nature, playing live.

“‘On the road again…’” he sang playfully. “Touring, that’s the other half. You don’t feel total until you’re out there actually playing. We’re starting to loosen the machinery. Eric keeps asking could he come on, and George is there – he says: ‘I’ll roadie, I’ll do anything.’”

Jim Capaldi left us after what became his final solo album, 2004’s Poor Boy Blue, yet again featuring Winwood, and Gary Moore. He was steadfastly proud of the music he made on his own and in the company of cherished friends, and especially of the records, and the spirit, that Traffic had given the world.

“I was at a Neil Young concert a few years ago at Madison Square Garden,” he said, “and there were a lot of kids. I was sat there and we started talking, and they knew who I was. They said they were heavily into The Doors and Traffic, and they were eighteen, nineteen, twenty-year-olds. It was great.

“I think that music is timeless, really. If you listen to it and examine it now, I don’t think you can come up with anything that will make that sound old. It reached a total spectrum.”

Short Cut Draw Blood is now available digitally. Traffic’s six studio albums from 1967- 74 are out now in 180g vinyl editions. More info at jimcapaldi.com