With 100,000 fans packed into Sao Paulo’s grand Estádio Cícero Pompeu de Toledo on the evening of January 16, 1993, the biggest show of Nirvana’s career should have been a cause for celebration, an affirmation of the band’s status as the pre-eminent act at the vanguard of a new rock revolution. In reality, depending upon your perspective, the Seattle trio’s performance at the Hollywood Rock festival was either one of the greatest punk rock shows ever or a pitiful display of petulance from a band whose view of their audience often skirted perilously close to contempt.

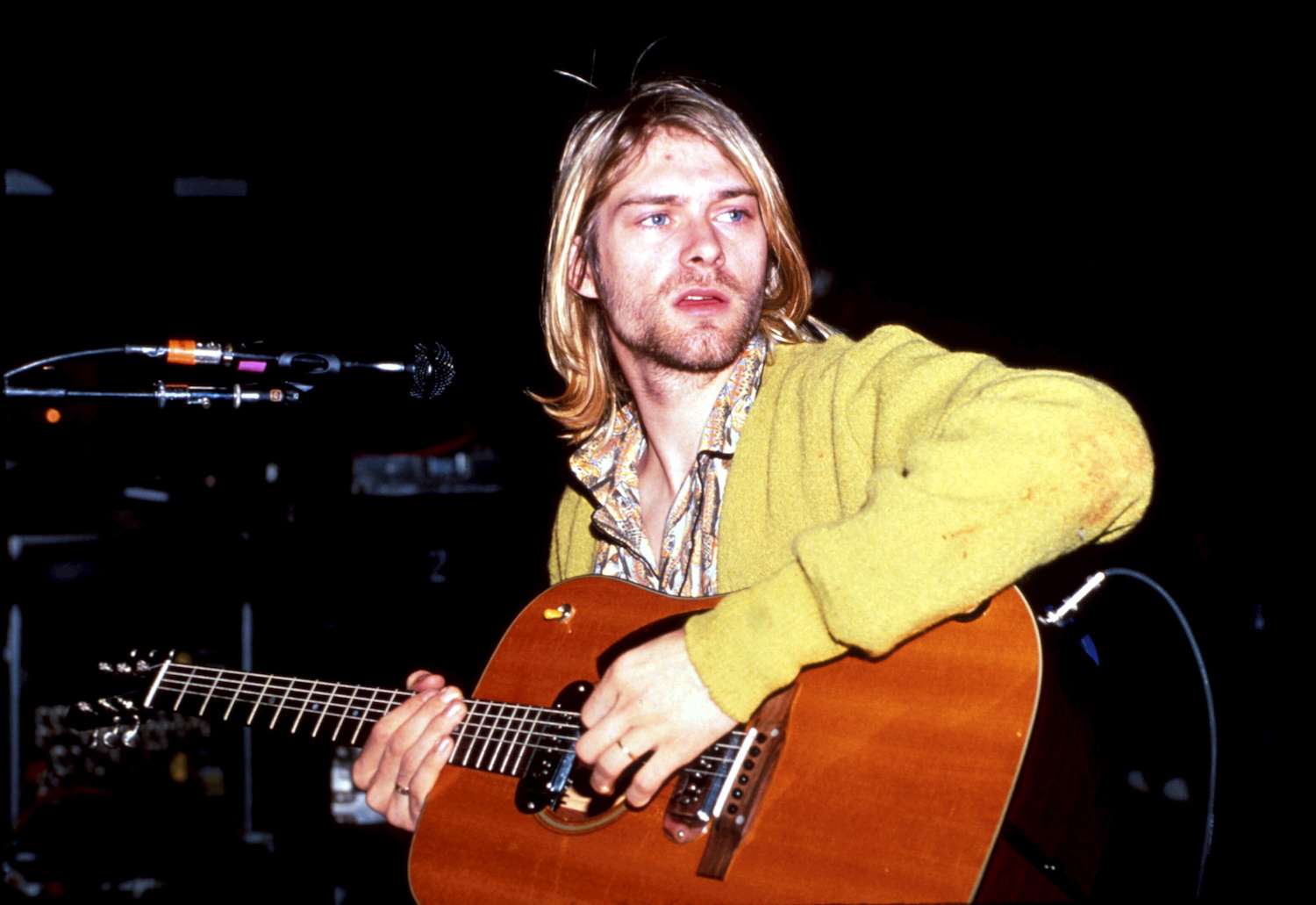

Onstage, Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl knew that something was amiss from the moment Kurt Cobain stumbled through the opening riff of School, the set’s opening number, at quarter pace. Nirvana’s frontman’s decision to mix alcohol with painkillers pre-show had ensured that he was, in Grohl’s recollection, “high as fuck.”

“Krist and I looked at one another like, ‘Holy fucking shit! What’s about to happen?’” Grohl remembered. “It was kind of terrifying. And, as Nirvana always did, we somehow managed to sabotage the show.”

Thirty minutes into a shambolic set blighted by scuffed notes and off-key vocals, an embarrassed Novoselic had had enough. Unshouldering his bass, he launched the instrument across the stage at Cobain and walked off into the wings. Confusion reigned before the bassist was cajoling into returning by Nirvana’s tour manager Alex MacLeod, who was aware that the group would forfeit their appearance fee if they failed to fulfil at least 45 of their contracted 90 minutes onstage. Novoselic reluctantly rejoined the fray without even bothering to retune his bass, figuring that the band couldn’t possibly sound any worse. In this assumption, he was entirely incorrect. After fumbling through obviously unrehearsed snippets of Iron Maiden’s Run To The Hills and Led Zeppelin’s Heartbreaker, the trio swapped instruments for a rock ’n’ roll covers set that verged on performance art. By the time the group had chewed through excruciating interpretations of Queen’s We Will Rock You (during which Cobain altered the chorus to sing “We will fuck you”) and Terry Jack's 1974 MOR standard Seasons In The Sun thousands of bewildered, affronted patrons were already streaming towards the exits.

Those who left early, however, would miss the most intriguing part of the evening, the unveiling of two brand new songs destined for Nirvana’s keenly anticipated third album. The first of these, Heart-Shaped Box, exhibited a bruised melodicism betraying Cobain’s long-held love of The Beatles, the second, the lurching sludge rock of Scentless Apprentice, was delivered as an over-amplified primal scream. Taken together, the two tracks, and the chaotic 80 minutes which prefaced their premieres, threw up more questions than answers as to Nirvana's future. In the wake of the phenomenal success of Nevermind, rumours persisted that its follow-up would be the trio's career suicide note, a nihilistic kiss-off to a mass market constituency who had the temerity to like that album’s "pretty songs" and file it alongside 1991's other blockbuster sets from Guns N’ Roses, Metallica, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Pearl Jam. The reality would infinitely more nuanced, and consequently more fascinating.

“Nobody knew what kind of album we were going to make next,” Dave Grohl told this writer. “But by the time we got to Brazil, it started becoming clear that it wasn’t going to be the sugar-coated pop of Nevermind. It was going to be darker, and more dissonant, and noisy. I’m almost positive that the label wanted us to just recreate Nevermind, because it’d be a safe way to sell another 30 million records. But, of course, we weren’t going to do that.”

It was a really strange time: there was tension, there was weirdness

Dave Grohl

Nevermind knocked Michael Jackson’s Dangerous from the summit of America's Billboard 200 chart on January 11, 1992. It was a watershed moment for the alternative rock community. Not least because it signalled the beginning of the end of Nirvana’s career as a fully-functioning rock band.

That same weekend the trio were in Manhattan to perform on Saturday Night Live, arguably America’s best-loved television programme. After showcasing Smells Like Teen Spirit and Nevermind's most chaotic punk blast Territorial Pissings, the three-piece set about gleefully trashing their equipment, with Cobain French-kissing Krist Novoselic as the show’s end credits rolled.

The performance served noticed that the nation’s new favourite band was a very different proposition than any which mainstream America had previously embraced. And yet, it was one bedevilled by familiar curses. Ducking out of the SNL after-show party early, Cobain returned to his Midtown hotel room, shot up a quantity of China White heroin which he had procured earlier that day in the city’s notorious 'Alphabet City' district, and passed out. At 7am, his pregnant girlfriend, Hole's Courtney Love would find him unconscious on the floor. It was Cobain’s first overdose.

Rumours about the singer’s drug use had been circulating for months. Indeed, that very week, the Californian music paper BAM had hinted at the possibility that Nirvana’s frontman had acquired a habit. While Nirvana’s management company moved swiftly to publicly dismiss the story as sensationalist gossip-mongering, in private they acknowledged that the singer needed help. Tentative plans to stage a run of summer arena dates to capitalise on the success of Nevermind were shelved, and it was agreed that Nirvana would come off the road upon the completion of their January/February touring commitments in Japan and Australia so that Cobain might receive treatment. In total, the band would play just 35 shows in 1992. By way of comparison, Metallica, whose ‘Black Album’, released six weeks prior to Nevermind, was still in the Billboard Top 10 when the Seattle trio hit Number 1, racked up some 167 dates across the same 12 months.

At the tour’s conclusion, Cobain and Courtney Love wed on Waikiki Beach in Hawaii. Krist Novoselic and his wife Shelli, who'd been unafraid to call the couple out on their increasing heroin dependency, were not invited. The following month, the newly-weds moved from Seattle to Los Angeles, renting an apartment on Spaulding Avenue in the city’s gritty Fairfax district. Here, Cobain focussed on his art and sculpture, only occasionally picking up a guitar while high: “I did all my best songs on heroin this year”, he later told Musician magazine.

The singer also re-drafted Nirvana’s publishing contract, which had previously stipulated that all royalties would be split evenly between the three band members: under the terms of the new arrangement, Cobain would receive the lion’s share of the monies accrued. To his bandmates’ dismay, Cobain also insisted that the new contract be applied retroactively to the September 1991 release of Nevermind, meaning that Novoselic and Grohl now effectively owed him money from the album sales. Bitter arguments ensued and for a few anxious weeks no-one was entirely sure whether Nirvana actually still existed as band. It was, says Dave Grohl, looking back, “a really strange time: there was tension, there was weirdness.”

On April 7, the trio regrouped at the West Seattle home Grohl shared with his longtime friend and drum tech Barrett Jones for their first recording session since the stint at LA’s Sound City Studios which had yielded Nevermind. With Jones producing on the 16-track desk in the apartment’s basement, the band cut three tracks - Return Of The Rat, Oh, The Guilt, and Curmudgeon - in a matter of hours. During downtime, Cobain also took the opportunity to show his bandmates rough sketches of two new songs he had penned in Los Angeles, Very Ape (then provisionally titled Perky New Wave) and Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle.

“We hadn’t jammed with each other since we stopped touring for Nevermind, and you know, that's a funny feeling,“ Grohl recalled. “It’s like going out on a date with one of your exes and trying to have sex again, it’s just weird. But I remember Kurt showing us those songs that day, and that’s when the lightbulb went off and I knew, ‘Oh my God, we’re going to have another record.’ I thought, ‘Wow, these are good songs, and we’re going to have another great record’.”

Nevermind was more pop, and a little bit more commercial: now we’re reverting back to the weirder stuff

Kurt Cobain

Kurt Cobain had been compiling songs for Nirvana’s third album even before Butch Vig had set the tapes rolling on Nevermind. Written in the Olympia apartment he and Grohl shared in 1990/1991, Pennyroyal Tea was first aired at the same April 17, 1991 show at Seattle’s OK Hotel where Nirvana premiered Smells Like Teen Spirit, while rough sketches of the baleful All Apologies (then titled La La La) and the scathing Radio Friendly Unit Shifter (originally titled Nine Month Media Blackout) had been committed to two inch tape by the band’s live sound engineer Craig Montgomery at Seattle’s Music Source studio on New Year’s Day 1991. Dumb, a deceptively pretty song referencing Cobain’s burgeoning heroin habit, had been part of the band’s live set since 1990 and first surfaced in recorded form as part of a radio session recorded for John Peel’s Radio 1 show on September 3, 1991.

The centre-piece of the album however, in Cobain’s eyes, was to be a new song authored in the bathroom of his Spaulding Avenue apartment. Taking its title from a trinket given to the singer by Love in the early days of their relationship, Heart-Shaped Box was Cobain's most achingly tender yet deeply twisted love song yet, a lyric poem for his wife winding his familiar obsessions - entrapment, dependency, addiction - into a raw, affecting meditation upon consumptive love.

The sickness at the heart of the couple's relationship was exposed in the most terrifying manner in the summer of 1992. While Cobain was detoxing in the Cedars-Sinai health centre, a profile of Courtney Love was published in Vanity Fair magazine. A compelling read, the article quoted Hole’s singer as saying that she can continued using heroin weeks after discovering she was pregnant, claims which the couple would later furiously deny as social services began to ask questions of their own. On the morning of August 18, Love gave birth to a healthy baby girl, Frances Bean Cobain, at Cedars-Sinai with her husband passing into unconscious by her bedside. The following day a strung-out, delirious and paranoid Cobain returned to the maternity wing with a handgun secreted in his hospital gown and tried, unsuccessfully, to convince his wife to join him in a suicide pact. Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson smuggled the weapon out of the facility for the couple’s own safety.

Five months on, with a week free between the Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro legs of the Hollywood Rock festival, Cobain and Love sought to document some of the madness enveloping them by taking their respective bands back to the studio to track some new recordings. The working title of Nirvana’s third album was I Hate Myself And I Want To Die: Love had determined that Hole’s second album would be titled Live Through This. The couple’s shared love of gallows humour was nothing if not striking.

Nirvana's last recording session had been a frustrating affair. Inspired by the off-the-cuff session with Barrett Jones, Cobain had made a two day booking at Seattle’s Word Of Mouth studio with Jack Endino, Sub Pop’s de facto in-house producer, who had manned the desk for the band‘s 1989 debut Bleach. But on October 25, the first scheduled day of recording, the singer failed to materialise: that neither Grohl nor Novoselic voiced much complaint was as bemusing to Endino as Cobain’s no show. The following afternoon, the singer appeared without a word of apology, and the band laid down six instrumental tracks and a ragged vocal take - for Rape Me, a fiercely confrontational sister piece to Nevermind’s harrowing Polly - before the arrival of Cobain's wife and infant daughter effectively called time on the session.

The group who showed up to studio B of BMG’s Ariola Ltda facility in Rio on January 19 were infinitely more focussed and purposeful. With the horrors of the Sao Paulo show behind them, the band had spent their downtime in Rio sight-seeing, sun-bathing, hang-gliding and indulging in what the bassist remembers as “a lot of debauchery” with their friends in L7, the Red Hot Chilli Peppers and Alice In Chains, and consequently were in a much more agreeable frame of mind. With soundman Craig Montgomery manning the studio’s vintage Neve board, over three consecutive evenings the trio navigated their way through seven new tracks - Heart-Shaped Box, Scentless Apprentice, Very Ape, Milk It, Moist Vagina, experimental noise-fest Gallons of Rubbing Alcohol Flow Through The Strip and the darkly sarcastic I Hate Myself And I Want To Die. A band version of Cobain’s favourite guilty pleasure Seasons In The Sun was also tracked, and Dave Grohl amused himself with a knockabout solo take on Forward Into Countless Battles by Swedish underground metallers Unleashed.

“I think we’re going in a more experimental, New Wave type direction,” Cobain told MTV Brazil's Zaca Camargo when he dropped by the studio. “We used to be more Gang Of Four/New Wave influenced, more experimental with more noise and different effects boxes and stuff, and then we started getting too much into straight-ahead guitar grunge music, and that’s pretty much what Bleach was like. And then Nevermind was more pop and a little bit more commercial and now we’re reverting back to the first thing, just weirder stuff.”

Our A&R man at the time, Gary Gersh, was freaking out.

Dave Grohl

Cobain already had a definite idea as to the producer who could help realise his vision for Nirvana's third album. His choice had set alarm bells ringing in the boardroom of Geffen Records.

Steve Albini had a reputation within the corporate music industry as a professional pain in the ass. Formerly a fanzine writer with a penchant for winding up the more po-faced members of the underground community, Albini started his first band Big Black while studying journalism and art at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois: with graphic lyrics dissecting child abuse, domestic violence, racism and misogyny allied to sheet-metal guitar riffing and harsh, skittering drum machine beats, the group were every bit as brutal, confrontational and provocative as his writing.

Albini's liner notes for their posthumous 1992 live album Pigpile provide an excellent insight into the basic principles which informed his work. “Treat everyone with as much respect as he deserves (and no more),” he wrote. “Operate as much as possible apart from the 'music scene.’ Take no shit from anyone in the process.” Post-Big Black, Albini carved out a career as a recording engineer, working with artists such as The Jesus Lizard, Superchunk, Slint and Urge Overkill. In 1992, when Kurt Cobain was asked by England’s Melody Maker magazine to nominate ten records that changed his life, he listed The Breeders’ Pod and Pixies’ Surfer Rosa as his number one and two choices: Albini had recorded both albums. In their stark, unvarnished sound Cobain heard a blueprint for Nirvana's new direction. Beyond this, there was also a 'fan boy' element underpinning Cobain's decision: in his journals, he had listed Big Black's 1986 debut album Atomizer as one of his favourite records, and he'd been in the audience when Albini's band played their last ever show, at the Georgetown Steamplant in Seattle on August 11, 1987.

Albini set out some ground rules before agreeing to take on the assignment. He insisted that if Nirvana wanted to record with him, they should come to the studio fully prepared: he proposed a recording schedule of just two weeks. Furthermore, he suggested that the band should lay out the $24,000 fee for the session themselves rather than relying on Geffen's largesse: this, he maintained, would ultimately give them a greater degree of autonomy in the process. Wary of corporate interference, as he had been throughout his career, Albini also drew up a contract between himself, Geffen and the band, insisting that all parties acknowledge that whatever album Nirvana might make with him would be released as recorded. Tellingly, no-one from the label would commit pen to paper on the document.

“Our A&R man at the time, Gary Gersh, was freaking out,” Dave Grohl admitted in 1993. “I said, ‘Gary, man, don’t be so afraid, the record will turn out great!’ He said, ‘Oh, I’m not afraid, go ahead, bring me back the best you can do.’ It was like, ‘Go and have your fun, then we’ll get another producer and make the real album.’”

“I don’t think [the label] were behind it,” Krist Novoselic added. “But we’d sold enough records to do whatever the hell we wanted.”

We wanted to impress Steve Albini. He was our hero.

Dave Grohl

On February 12, 1993 Cobain and Novoselic flew to Minneapolis - St. Paul International Airport, where recording engineer Brent Sigmeth was waiting to take them to Pachyderm Recording Studio, a residential studio in Cannon Falls, Minnesota: Dave Grohl joined them a day later. Nirvana were finally getting back to the business of being a working, creative rock band once again. The two weeks that followed would be an oasis of sanity, productivity and celebration amidst the turmoil that too often enveloped the group.

It was Albini’s decision to record at Pachyderm. Located in a 50-acre private forest, the studio was a reasonably-priced facility favoured by musicians who liked to work on their art without external distractions. Albini had recorded The Wedding Present’s 1991 album Seamonsters album at the studio and had returned in December '92 to helm sessions for PJ Harvey’s Rid Of Me: he admired the studio's acoustics, and its vintage Neve 8068 recording desk, formerly located at Electric Lady Studios in New York, where it was used to mix AC/DC's Back In Black.

“A number of reasons coalesced for choosing Pachyderm,” Albini recalled. “The places that they’d used before in Seattle and LA I wasn’t familiar with: they’d recorded at Smart in Madison and I knew that studio somewhat, but I knew Butch [Vig, Smart’s co-owner] and I thought it might have been slightly uncomfortable for them to go there with another engineer and do a record and not have Butch involved. Plus they had a lady at their management company or label who’d said that they were concerned about Kurt having access to drugs and Madison was a college town and had a bit of a drug subculture, so that seemed like a bad idea, and in other places that had fancy studios he knew people that would probably turn up and mule for him and that seemed like a bad idea too.

“This place in Minnesota, besides being, acoustically, a very nice studio, was 50 miles out in the woods, so it wouldn't be the case that anyone would just turn up or that Kurt would just wander off into the city. So it seemed like a good option.”

“If you’ve ever been in Minneapolis in February, it’s like an ice planet, I swear to God,” Dave Grohl told this writer with a laugh. “During the day it was fifteen degrees below zero. At night it went down to twenty-five, thirty degrees below zero. It was fucking freezing: the coldest I’ve ever been in my entire life. So, we were in total isolation and locked indoors because if you stepped outside you’d die. But it was a beautiful place, and an unusual place to record.”

As the band settled into their new environs, Albini placed a proposition before them. He proposed playing a single frame of pool: if Team Nirvana won, he would waive his $100,000 fee for the session. If the producer won, however, the trio would be required to double his money. The band refused to take the bait.

“I think they were a little more risk adverse than I was,” Albini said with a shrug.

Work on Nirvana's third album began on Valentine's Day 1993. The band set up their own equipment, Albini positioned his microphones and recording of the basic tracks began immediately.

“When we talked to him before recording,” Grohl told me, “he made a point about, ‘Are your songs prepared? Are you going to come into the studio and fuck around for two weeks? Are you going to write in the studio?’ We said ‘No, no, no.' We set up and recorded.”

“More than the intention of making a great record, we wanted to impress Steve Albini. He was our hero. He was making albums that sounded so real and so powerful with such a signature sound, sonically he was just untouchable. I remember taking Pod and the first Jesus Lizard record down to Los Angeles to Sound City and referencing those albums, like ‘This is the drum sound we want to get, this is the sound that we like.’ And of course it didn’t really turn out that way. But everybody was looking forward to meeting with Steve not only so that we could have a Steve Albini album, but also so that we could show him like, we're for real: whatever you've seen on television, whatever you've read in the newspapers, forget that, watch us play Scentless Apprentice, we're for real.”

“We could really play well when we wanted to,” Novoselic added. “The first song we recorded was Serve The Servants, and we did it in one take. Albini was like ‘Are you fellas ready?’ and we're like ‘Yeah, go ahead’ and he presses 'Record' and we just busted the song out. We finished the song and looked at each other, like, ‘Yeah, that was good.’ And Steve’s like, ‘Yeah, that was good. Okay, let's do another one’.”

“One of the beautiful things about that album was that it was recorded in that way,” Grohl said. “Had we laboured over that album, or picked it to shreds with a heavy-handed producer, it would not have been the same album.”

“The sessions went really smoothly,” Albini remembered. “None of it was difficult. They'd sent me their demos from Brazil and they were pretty skeletal - there were really only a couple of proper songs there - so I was a little bit surprised that when they got to Minnesota, it seemed like things had fleshed out quite a bit. I thought they were all excellent musicians, particularly Dave, who is an absolute monster of a drummer.”

After just one week at Pachyderm, the trio had laid down basic tracks for 17 songs, most recorded in one or two takes.

“It was real quick,” Grohl recalled. “That's the thing with working with Steve: Steve's not going to dive in with his scalpel and surgically deconstruct the song that you've just made as a band. He appreciates the idea that a band does what a band does, and he's just there to document or capture that moment. And what I love the most about that album is the sound of urgency and the sound of the three of us, that's really the three of us in a room playing.”

As week two of recording began, an uninvited guest joined the trio: Courtney Love had decided to pay her husband a surprise visit. The singer's louder-than-life personality rather disturbed the vibe at Pachyderm: Albini would later label her a ‘psycho hose beast.’ Despite the disruption, Nirvana completed the recording of their new album one day ahead of schedule. Albini dispensed wine and cigars to all present, and the mood was celebratory. The trio left Cannon Falls in high spirits. This buoyant mood would soon be deflated: in mid-March, Kurt Cobain phoned Albini to tell him that Gary Gersh hated their record.

“My A&R man called me up one night and said, ‘I don’t like the record, it sounds like crap, there’s way too much effect on the drums, you can’t hear the vocals’,” Cobain later recalled. “He didn’t think the songwriting was up to par.”

“I think the actual quote was ‘Are you kidding?’” said Grohl. “Kurt basically said ‘No, this is it, we are Nirvana and this is the record.”

Writing in his journal at the time, Kurt Cobain imagined a scenario whereby his band’s provocative album would be issued first on vinyl, cassette and eight-track cartridge only, before Geffen forced the release of a neutered remix on CD, sold as the ‘Radio-Friendly, Unit-Shifting Compromise Version.’ In reality, however, it would be self-censorship rather than corporate intervention which ultimately dictated the sound of the album presented to the record-buying public. In late March Steve Albini received a second phone call from Cobain. On this occasion Nirvana’s frontman was markedly less enthusiastic.

“He said they were starting to believe that they were unhappy with the record and they wanted to remix some stuff,” Albini recalls. “And I said, ‘Okay, well, I’ll give it a listen and if I feel I can do any better or if I feel like there’s specific stuff I can change then I’ll be happy to give it a shot.’ And so I listened to the master again at home in Chicago and I really felt pretty strongly that I couldn’t improve on what we’d done. And after doing that, I called Kurt back and said, ‘Well, what exactly did you want to do, like how many songs and what did you want to do?’ And he said, ‘Well, basically everything.’ Kurt might have been in a vulnerable state at that point - I don’t know if his drug use kicked back in or if he started to fear for his pension or whatever - but as soon as he said that I realised that there was something up and that it didn't have anything to do with whether or not they were actually satisfied with the record.”

I don't harbour any bad feelings towards the band... but literally every other person involved in that record was an asshole

Steve Albini

“The first time I played it at home I knew there was something wrong,” Cobain told Melody Maker in 1993. “The whole first week I wasn’t really interested in listening to it at all, and that usually doesn’t happen. I got no emotion from it, I was just numb. So for three weeks we listened to the record every night, trying to figure out what was wrong with it, and we talked about it and we decided that the vocals weren’t loud enough, the bass was inaudible and you couldn’t hear the lyrics. That was about it. We knew we couldn’t possibly re-record because we knew we’d achieved the sound we wanted. So we decided to remix two of our favourite tracks.”

On April 19 these private conversations tumbled into the public domain when the Chicago Tribune ran a story titled ‘Record Label Finds Little Bliss In Nirvana’s Latest.’ In journalist Greg Kot’s article Steve Albini admitted that Geffen hated the recording and said “I have no faith this record will be released.” Kot also quoted unidentified sources at Geffen who claimed the album was “unreleasable.” The article was transmitted by media outlets worldwide, with outrage growing over what was perceived as corporate interference in Nirvana's art. Such was the clamour to disperse this interpretation of the facts that on May 11 Geffen issued a press release refuting the story. By now R.E.M. producer Scott Litt was already ensconced at Heart’s Bad Animals Studios in Seattle remixing the album’s two prospective singles, Heart-Shaped Box and All Apologies.

“There was an element where we were thinking ‘We’re a big band, we might as well face up to it’,” Krist Novoselic admitted to this writer.

“Kurt was very clear in his vision of what he wanted the record to be,” Dave Grohl confirmed. “I do remember there being some tension between Kurt and Albini. But ultimately Kurt was going to get what he wanted.”

“Up to the point where we finished the mixes on that record I had a pretty good time working with Nirvana,” Steve Albini told me, “and it remains a pretty good memory for me. After that - once the management company and record label started turning the heat up on the band and they started dropping shit into the press - it got really ugly.”

“I don't harbour any bad feelings towards the band, it was people external to the band who were pulling this bullshit. The three guys in the band were perfectly reasonable and easy for me to deal with, but literally every other person involved in that record was an asshole.”

In the third week of July ’93, Nevermind finally dropped out of the Billboard 200 after 92 weeks on the chart. By coincidence, that same week had been earmarked for Nirvana to unveil their new album to the world’s press. The trio booked a show at New York’s Roseland Ballroom on July 23 during the city’s annual New Music Seminar and invited representatives of the world’s major media outlets to attend. Those who accepted were handed a cassette tape bearing the title In Utero. That evening, Nirvana would perform nine tracks from that cassette in front of an audience of just 3,500 people. Only a handful of those in attendance were aware that Kurt Cobain had almost died that same day.

The singer had received a delivery of heroin at the Omni Berkshire Place hotel the previous afternoon. His decision to use ahead of one of the most-eagerly anticipated gigs of Nirvana’s career led to furious, and prolonged, arguments with his wife. Those closest to the couple initially opted not to intervene, but Frances Bean’s nanny Michael 'Cali' DeWitt and Nirvana’s UK press agent Anton Brookes became concerned when silence descended upon the hotel suite.

“I was upstairs, and suddenly the screaming, or the arguments, changed,” Brookes recalled. “We realised we should go in. We went rushing into the bathroom and slumped behind the toilet was Kurt with a syringe in his arm, blue. He was lifeless.”

Brookes and DeWitt jolted Cobain back into consciousness by splashing water on his face and punching him repeatedly in the stomach. When hotel security turned up, Brookes begged them not to call the police, and removed all traces of drugs from the room, flushing bags of heroin down the toilet. The PR swore the journalists in his charge to secrecy.

The following afternoon, during an interview with UK music writer Amy Rapheal, Cobain discussed the question of whether or not there is life after death.

“I believe if you die you’re completely happy and your soul somehow lives on and there’s this positive energy,” he mused. “I’m not in any way afraid of death. I’m afraid of dying now, I don’t want to leave behind my wife and child, so I don’t do things that would jeopardise my life. I try and do as little things as I can to jeopardise it. I don’t want to die. I’ve been suicidal most of my life, I didn’t really care if I lived or died, and there were plenty of times when I wanted to die, but I never had the nerve to actually try it.”

Nine months later, Cobain would face up to those fears, with tragic consequences.

In Utero was released to the world in September 1993. Those who listened discovered an uneven yet utterly compelling body of work, by turns horrifying, hilarious, pitiful, harrowing and venomous.

Knowing how much scrutiny the album would be placed under, Cobain's decision to introduce the collection with the lyric “Teenage angst has paid off well, now I'm bored and old” (on Serve The Servants) displayed breath-taking chutzpah: elsewhere he sounds less confident, as befits a man desperately seeking psychological stability even as the tectonic plates beneath his feet are shifting. In truth, it’s a profoundly confused, conflicted album, neither the unlistenable career suicide note many feared nor a wholesale dismissal of grunge formulas. But the poignant All Apologies read suspiciously like a shrug of resignation from a man instinctively sensing that his happiest days are behind him.

“One of my favourite lines in a Nirvana song - which is fucking dark and I didn’t realise its weight until I sat in my house in Seattle playing [Fugazi frontman] Ian MacKaye the first mixes of In Utero, without a lyric sheet - is the line on Scentless Apprentice where Kurt sings ‘You can’t fire me because I quit’, Dave Grohl told this writer in 2010. “Ian heard that and he goes, ‘That’s fucked up.’ And I realised, ‘Wow, that is fucked up.’ If there’s one line in any song that gives me the chills it’s that one. Maybe all those things that people wrote about him painted him into a corner that he couldn't get out of.”

The way it ended was just cruel and unforgiving

Krist Novoselic

“The way it ended was just cruel and unforgiving and you can’t revoke it, it’s just terrible,” Krist Novoselic reflected. “I told him not to do heroin. I told him. But he didn’t listen. He told me the first time he did heroin, and I said, ‘Don’t do it.’ But he didn’t stop. When I think of that time from Nevermind to when Kurt died, it seemed like it was ten years because there was so much going on, but it was only like a few years. It was really intense. It was such a whirlwind and it's too bad. But we have the music, and lots of positive memories: the band liked to laugh a lot and we had a good time. And we liked to play together, and you can hear that on In Utero.”

“Nevermind and In Utero are two totally different albums,” said Grohl. “Nevermind was intentional: as much as any revisionists might say it was a contrived version of Nirvana, it wasn't, we went down there to make that record, we rehearsed hours and hours and hours, day after day, to get to Nevermind. But In Utero was so different. There was no laboured process, it was just - bleurgh! - it just came out, like a purge, and it was so pure and natural. And both of those things I'm very proud of. If you can make one of those albums in your lifetime you're lucky, we got two in a row, and that’s awesome.

“Obviously In Utero was a direct response to the success and sound of Nevermind, we had just pushed ourselves in the other direction, like ‘Oh really, that’s what you like? Well here’s what we're going to fucking do now!’ But it’s a hard album for me to listen to from front to back. Because it's so real and because it's such an accurate representation of the band at the time, it brings back other memories. It kinda makes my skin crawl.”

“I hear a really weird rock record and I also hear a lot of Kurt Cobain's artistic sensibilities,” Krist Novoselic added. “Because Kurt was a painter and a sculptor and his sensibilities as a true artist meant that everything had to be kinda weird or cryptic. He made me this sculpture once, and I still have it, which is this writhing spirit person, it's kinda weird and beautiful. When I hear In Utero it's kinda the same: I mean, it's a rock record, with big riffs, and melody, but it's also kinda dark. It's a strong record. It's a testimony to Kurt Cobain’s artistic vision and it's powerful and the messages resound with people. I’ll get Twitter comments or fan mail, where people say ‘Oh, I went to rehab, or I had a bad family life, and I had a bad time and In Utero brought me through it.’ And that’s great, that’s cool. And that’s a big dedication to Kurt Cobain.”

“It’s funny,” Dave Grohl concluded, “I spend a lot of my time planning on things to come, I don't spend a lot of time thinking back on things I've done. But In Utero, man, what a trip.”

For more of Dave Grohl's reflections on life in Nirvana, and his musical journey before and after his time in the band, pick up This Is A Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl, where excerpts of this feature were first published.