Genesis were back on the road in the autumn of 1971 promoting Nursery Cryme. Apart from the ‘Six Shilling Tour’ it was still random dates here, there and everywhere, still working as hard as we could. I don’t ever remember more than a couple of days off a week and anyway, a day without a gig was never a day off for me because I was always chasing around, going to the office, picking up wages, dealing with Fred, buying tambourines and strings, getting microphones repaired. A roadie’s work is never done. I used to go to Charlie Foote’s legendary drum shop in Golden Square for Phil’s sticks. Fortunately it was around the corner from Brewer Street, where Charisma’s office was located.

Aside from my rather liberated relationship with Betsy, there wasn’t much interaction between the bands on the label, or even with other bands playing the same venues. They might have appeared next to each other in the pages of Melody Maker but they never saw each other because they were all out on the road working. Not long ago, Tony Banks appeared on a Prog Rock Awards show and the presenter asked him what he thought about other prog bands like Yes, ELP, Jethro Tull and Pink Floyd. His reply was, “We absolutely hated them. They were the competition.” (Tony’s always been incredibly honest, often to his own disadvantage.) So this idea of them all being lovey-dovey prog groups together, all supporting and admiring one another was a complete fantasy. I know Tony wouldn’t have admired Lindisfarne musically because their style was too harmonically simple for his taste, yet he couldn’t not be impressed by the way they got the audience going.

Any rivalry between the bands didn’t extend towards the road crews. There was certainly plenty of camaraderie among the roadies who worked for the bands on Charisma. We were all doing the same job, as well as we could. Van der Graaf Generator had an outrageous pair called Crackie and Nodge. Crackie ended up becoming Strat’s trusted driver. He was a largish, chronically asthmatic Welshman while Nodge, also Welsh, was a skinny little guy with a patch over one eye. They were chalk and cheese. At one of the gigs on the ‘Six Shilling Tour’ we could move the gear to and from the stage through a trap door that would have been used for special effects. Crackie, in his lovely Welsh accent, said something about how it was like being down the mines. Of course he’d never been near a coal mine in his life.

On that tour, to ring the changes and alleviate the boredom that comes with staying in the same hotels and driving from one grimy northern town to another, we decided to swap passengers around in the vans. Two of the VdGG members, Guy Evans, the drummer, and Dave Jackson, the saxophone player, came with me in our van and from that day friendship grew between us. On another occasion, we needed to swap vans with them for some reason and it was pouring with rain, so I came up with this really clever idea of making the swap beneath the underpass at Paddington. We parked the vans back to back but slightly off-kilter so you could still get into both vehicles and transfer all the gear by sliding it along the floors of one van into the other.

Gradually the gigs got bigger and better. The equipment was improving too. It was around this time that we got a multicore – a long cable for all the on-stage mics – and this meant that I could position myself with the mixing desk half way back in the audience. On Foxtrot, the album after Nursery Cryme, there’s a picture of me in a top hat, taken at Tony and Margaret Banks’ wedding. Peter wrote a caption that read: ‘Faithful barefooted Richard, stage sound and sound friend’. I never wore shoes in those days. I didn’t see the point and I was letting my freak flag fly.

There were 10 or a dozen mics on stage to mix, certainly enough to mic up the drums. At one end of the multicore, there was a box into which they were all plugged; the cable then ran to the desk where it separated into more connections that plugged into the mixer. They were all numbered so you would know what was coming through what, and as the mixing process became more complex, it became more important for us to do a sound check before the show to get it all in balance. We always started with the drums and built the rest of the sound picture from there.

I taught myself to mix the sound on stage. I didn’t find it hard. My reference point would have been the recordings, even though, as I said earlier, I thought the first two records lacked the power Genesis had when they played live. Nevertheless, I knew what the balance should be. Mostly, my preoccupation was driven by trying to get Peter’s vocals to be audible through the instruments. He’s never had a naturally powerful voice and has always struggled to be heard clearly at live shows. As our tours wore on, he would also inevitably tend to lose vocal strength. I would do what I could to compensate, but it was difficult getting the vocals out as much as I would have liked. Tony Banks didn’t mind at all because he saw the vocals as being like another one of the instruments. This would always be an issue when they were mixing in the studio because Peter would always want the vocals up and Tony disagreed. Mind you, that’s not an uncommon thing with groups: singers wanting to be heard and the rest not really caring. Look at the Stones. You often can’t hear what Mick is singing but it doesn’t matter at all, it’s part of their style. I think that it also adds to the mystery.

Steve took care of most of the guitar parts and Mike, who was playing bass a bit on stage, would soon get a double-neck Rickenbacker, with bass and either 12-string or six-string guitar, that was specially made for him. He would switch between guitar and acoustic and bass pedals, which he got the following year at the time of Foxtrot. The lack of designated bass player was something unique to Genesis. Apart from The Doors, I can’t think of any other bands that didn’t have one.

One of our regular venues was Eel Pie Island, an eyot on the Thames near Twickenham with a footbridge that was just big enough to drive a small car across. The promoter there had a minivan so we would load it up – it would take three or four goes – and he would trundle the gear across. The hotel on the island was semi-derelict but it had a ballroom that was just about serviceable. I was amazed to discover that it had stages at either end. We performed there with Free, them at one end and us at the other. They did a set, we did a set, then they did another and we did another, all because we could leave the gear in place. Free were huge at the time, much bigger than Genesis, with a great bass player in Andy Fraser, and Paul Kossoff, a superb guitarist. Both are dead now, but what a band they were.

After the gig I stashed our mics into a duffle bag with a drawstring to tighten it at the top. We used the Mini for the larger pieces of equipment, quite possibly putting a strain on the footbridge. It was left to me to carry the last few smaller pieces over the bridge including the bag of mics. Somehow, the top mic fell out and landed in the river with an ominous plop. It’s still there. I certainly didn’t go in after it. This is the sort of incident that a roadie wishes he could forget.

It was always a slow build for Genesis. Strat, with his indefatigable belief in the band, was always looking for ways to promote his beloved protégés. He hit upon the idea of getting Keith Emerson, who had just formed Emerson, Lake And Palmer, to write a piece endorsing Genesis for publication in the music press. Keith wrote something along the lines of, “One day Genesis are going to be big and one day you’re going to wish you got in on the ground floor.” Nursery Cryme didn’t set the world alight but live it was terrific, particularly The Musical Box. It was a very well structured song and people used to go nuts at the end. Just last year Steve Hackett was doing his Genesis revisited show at the Royal Albert Hall and he played The Musical Box. I was in tears because the response was exactly the same as it had been with Genesis all those years before. Fifty years had gone by but the song still generated the same strong reaction in the crowd.

In retrospect, the most important events for Genesis during 1972 were the two first Italy tours, one in April and the next in August. Sandwiched between them were intense writing sessions of what would become Foxtrot. These took place down at Luxford and at a dance studio on Shepherds Bush Road. Once again Phil surprised us with an unexpected connection. Having attended the Barbara Speake Acting School as a young boy, subsequently appearing as the Artful Dodger in the 1960 London stage production of Oliver! and as an extra in A Hard Day’s Night, he was able to introduce us to the Una Billings Dance Studio and it was here that Supper’s Ready began to take shape. At 23 minutes, it took up the whole of the second side of Foxtrot – a big concept piece.

Banks has gone on record as saying it’s just a bunch of bits that they glued together, and in a way it was, but it’s still an amazing piece of music:

“That was an overall Genesis thing. Some of the pieces were made up from bits written by individuals, and the trouble was that we wanted to change the keys to make them fit. A prime example was Supper’s Ready where Willow Farm, which is in A flat major, was meant to lead on to a little flute melody in A minor. So we had to get between the two and we weren’t going to change Willow Farm and I wasn’t going to change the flute melody because I’d written it on the guitar and it was open strings, so we had to travel through these weird chords in between. When it comes out it’s a totally natural change, and you’ve got there without realising it. There’s another one at the end of that section, of course, which goes into Apocalypse in 9⁄8 which is a diminished chord, but on that occasion it was more like, you’ve built up this big expectancy and you think it’s going to be a major chord but it’s another chord, an F sharp minor which you are not expecting, and that’s an incredibly exciting chord change.”

Tony explains further:

“You think it’s going to resolve in a different way and then it goes into an unlikely chord and suddenly it’s very aggressive. I did that because I wanted to get to this F sharp minor change. This is quite technical but F sharp minor, a minor 6th was from a piece I learned at school called Night In May by Selim Palmgren, and it had a chord change in it and I always thought it was a great sound and we must use that. So I alternated between those chords before going into the solo.

“I’d written the thing and I wanted to try and keep it in that key and it produced quite interesting results, [so] rather than just everything being in the same key I made these adjustments, particularly in something like Supper’s Ready which is a very episodic piece. This was new. It was something I did in my own songs, so the chorus and the verse were in different keys. Holland Dozier Holland did that all the time on songs like Baby I Need Your Loving. It shifts and you think, ‘That’s great.’ The change itself is so good that it makes whatever you do afterwards sound really great. I did a lot of that in my own writing.”

Foxtrot was recorded at the Island Records studios in Basing Street and instead of John Anthony, John Burns was brought in to produce it. At last they had made an album where I felt that the production did justice to their sound.

When they’d finished rehearsing Supper’s Ready, they did the same thing they’d done with The Musical Box, inviting me to come and listen. As before, I’d been chasing around picking up wages and buying drumsticks, all the mundane tasks of my job. I then went down to the studio and sat and listened. Twenty-three minutes later my mind was blown; this was the most unbelievable piece of music I’d ever heard them play and happily, John Burns did a good job of capturing it on record.

The sessions for Foxtrot were bracketed by the two Italian tours. None of us really appreciated how well the band was going down in Italy, at least not until we got there and saw it for ourselves. Before leaving I raised my eyebrows a bit when I noticed that the scheduled gigs were going to be those palazzo dello sport places, medium indoor basketball arenas that were bigger than anywhere we’d played in the UK. I guess the Italian promoter knew what he was doing but it was still a surprise.

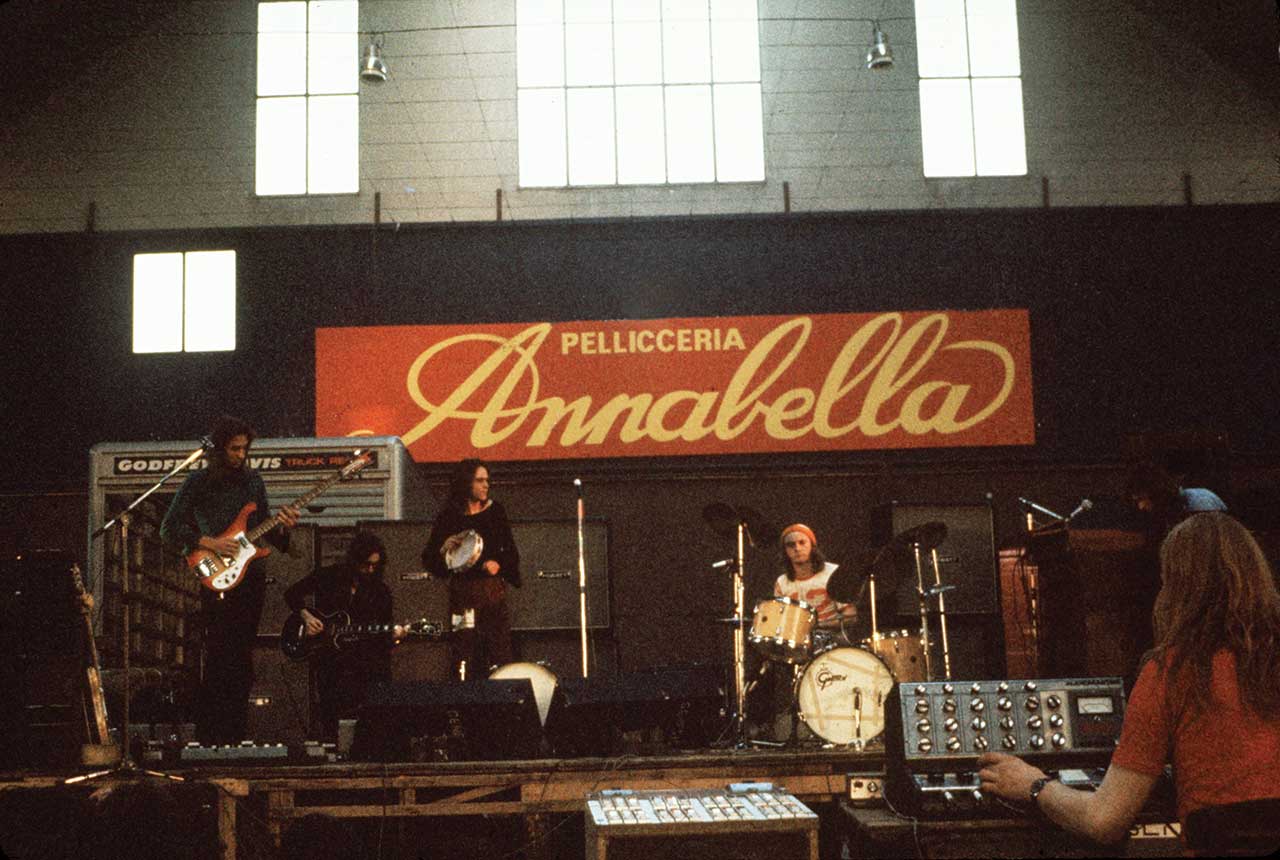

Bigger gigs meant we needed a bigger PA and that meant a bigger van. Before we went I got back in touch with our friend Reg King and told him we were going to need a three-tonner, which is the largest truck you can drive without a Heavy Goods Vehicle licence. Reg didn’t have a three-tonner so he subcontracted one from Godfrey Davis, the truck hire company. I went to Alperton to pick it up and Reg met me there, showing up on cue in his Cadillac. He said, “I haven’t told them you’re taking it abroad. If anything happens, bury it. Just leave it over there.”

Of course I had the carnet and all the rest of it but God knows if I was properly insured, probably not. Reg wasn’t one to worry about such details. The truck was easy enough to drive but when I first climbed into the cab, the one thing I couldn’t do was let the handbrake off. I didn’t recognise the unusual rod that came out of the dashboard. You had to pull and then turn to release it. I couldn’t figure it out. When the guy at Godfrey Davis asked me if I’d ever driven one before, I had brazenly replied, “Of course. No trouble, mate.” I managed to get it started but he had to show me how to work the handbrake. “It wasn’t like this on the last one I drove,” I insisted, never having driven one before. He gave me an odd look, probably not liking the length of my hair and my patent ignorance. I doubt Reg mentioned that the truck was being used by a rock band.

The other trick I had to learn was how to bleed the brakes when you parked up for the night. There was a big cylinder underneath the cab and it would make a loud hissing noise when you bled it. When you then started the engine it pumped up again. In those days I could still park it outside wherever I was living, so there was never an issue with what to do with the truck at night. As far as I’m aware we didn’t even have insurance for the gear that was left in the van, unattended of course. We didn’t worry about any of those details. It was an anonymous Godfrey Davis rental van, could have been full of anything – office furniture, fruit and veg or building materials. Eventually we bought our own three-tonner, with a cream cab and a brown box, quite a distinctive livery. Nobody would have known it contained Genesis’ priceless equipment.

So off we went to Italy, across the Channel, down through France and over the Alps. The band went in a van with actual seats and windows, accompanied by Paul Conroy from Charisma’s booking agency. There’d been some changes in the road crew by now. Gerard had gone and another old friend of mine called Paul Davidson, a school friend of one of my Millfield friends, Michael Reed, had taken over. He was at a loose end and became a great roadie mate. It’s funny to think that we were still recruiting roadies from the ranks of my school friends rather than professionals. That would come later.

So the conquest of Italy began. I remember driving down the Valle D’Aosta to Turin, Milan and Brescia, with breathtaking mountain scenery all the way. The promoter was called Maurizio Salvatore and he had arranged about 15 gigs for us, a substantial tour. We went down as far as Naples but no further south. The tour finished with a show on the outskirts of Rome. In those days there was a lot of political unrest in Italy that used to focus on rock gigs. This meant the police wouldn’t allow performances in the centre of towns, so you were always 20 miles or so outside in some sports arena.

On a typical day we’d get to the gig and it was wonderful for me because the venue would be completely empty and we would be met by a stage with huge loading doors at the back. We’d reverse in, up to the stage and out came the equipment, straight on to the stage, no carrying it along corridors or up the stairs, plus there were all these agreeably willing fans who would help with the gear. It made my job so much easier. The band then used the empty van as a dressing room. We’d get into the venue at around 11am, set up and then do a proper soundcheck, allowing plenty of time to get it right. These places were like cathedrals. You clapped your hands and you’d still hear the sound 12 seconds later, reverberating around the space. In some ways, mixing the sound was a bit academic – it was just swirling around – but it didn’t matter as the fans really loved it. After we’d set up and done the soundcheck, it would be about 1 or 1.30 p.m. and Maurizio would say, “OK. Mangiamo.” He always knew where the best restaurants were, so off we’d go for a huge lunch. We quickly learned how to eat in the style: first a pasta starter, often a scrumptious plate of incredible homemade spaghetti with a delicious sauce, then a slab of meat, no veg, maybe a bit of salad, and then a dessert like tiramisu. We also discovered fantastic wines to wash it all down with, so by the end of lunch, typically about 4pm, we’d be absolutely stuffed and out of it. We’d go back to the hotel, shut the blinds down with proper shutters to create complete darkness, collapse into bed and sleep like the dead for two hours and then get up and do the gig. Life was good. We would return to the sports arena and it would be packed with 5,000 fans, sometimes more, especially on the second tour when we might have up to 10,000 waiting to hear us.

I’ve often wondered why Genesis appealed to the Italians as much as they did. We met the Italian music writer and photographer, Armando Gallo, on these first tours and he cottoned on to us early and became a big supporter, eventually writing several books about the band. I think Italians appreciated the emotional content of Genesis’ music. It was romantic, like opera, and the songs resembled long suites. A fast and furious passage would often bring people to their feet. Being such avid fans the Italians had bought and absorbed all the records; this crowd knew every note and nuance of the songs. It was extraordinary really. We’d never experienced anything like it. There I was at the mixing desk in the middle of the audience and they were all clapping, a wonderful experience to see my boys being so understood and appreciated. The fans loved it all and gave the band standing ovations at the end of every show. It did wonders for their confidence and all five guys, Peter, Mike, Tony, Steve and Phil, have never forgotten the warmth of their early following in Italy, or its importance in their development as a band. I hope we paid our debt of gratitude by playing well for them.

Steve has another theory as to why Genesis were so popular in Italy:

“I think it has something to do with Catholicism. I think it’s to do with the theological nature of many of the songs. And it was partly that track Fountains Of Salmacis that audiences in the rest of the world didn’t understand at the time. That track… they got it immediately. I think they understood it because of the Greco-Roman connection. Catholic countries throughout the world subscribed to early Genesis. They liked the stories. These were very religious countries and it struck a chord deep within them. I have to go on record and say it was theatrical. I know that the others tend to distance themselves from that era but when they look at the early model they can’t understand why those albums still sell so well. But I feel that I do understand it.”

On the second Italian tour we had a bit of a problem on the way over because we didn’t know that in Europe they have a lot of extra bank holidays, religious holidays that were Saints’ days. The border was closed to us, not for cars but for trucks with a carnet, and we got stuck somewhere in the French Alps. Of course back then there were no mobile phones, no ATM bank machines, no credit cards, no internet, nothing. We only had enough cash to get us over to Italy, maybe to buy us a couple of meals, but no reserve and there we were stuck in the foothills of the French Alps until the border opened in a couple of days. So we retreated into the hills nearby. By this time there were a couple more roadies, one being Adrian Selby, Gerard’s younger brother who had joined us straight from school and eventually ended up taking my place. We slept rough under the truck and the next morning washed in a fountain in the middle of a tiny Alpine village.

All this meant we were about two days late getting to Rimini where the band were all waiting for us. Hearing nothing, they obviously thought the worst – that we’d driven off the edge of a cliff somewhere and had all perished. They were visibly relieved to see us but also a bit pissed off. Margaret Banks gave me a real dressing down. “Don’t you dare do that again,” she said to me. “You put us through hell.”

The other addition to the crew was a professional sound mixer to work our new mixing desk. He showed me how to use it, but by this time I had graduated to becoming Genesis tour manager, the guy with the briefcase who travelled with the band, looked after admin and no longer humped the gear. Until then I was just a general do-everything roadie, so you could say that I’d been promoted, in recognition of my long and devoted service. Not before time, though it soon made me realise that having reached this stage, maybe my horizons were beginning to expand, possibly beyond the world of Genesis.

My Book Of Genesis is available now from Argyll and Bute Publishing. See www.mybookofgenesis.com.

The story behind the song: Follow You Follow Me by Genesis

Wind & Wuthering: Genesis look back on their boldest prog statement