10 Roger Waters tracks every Pink Floyd fan should own

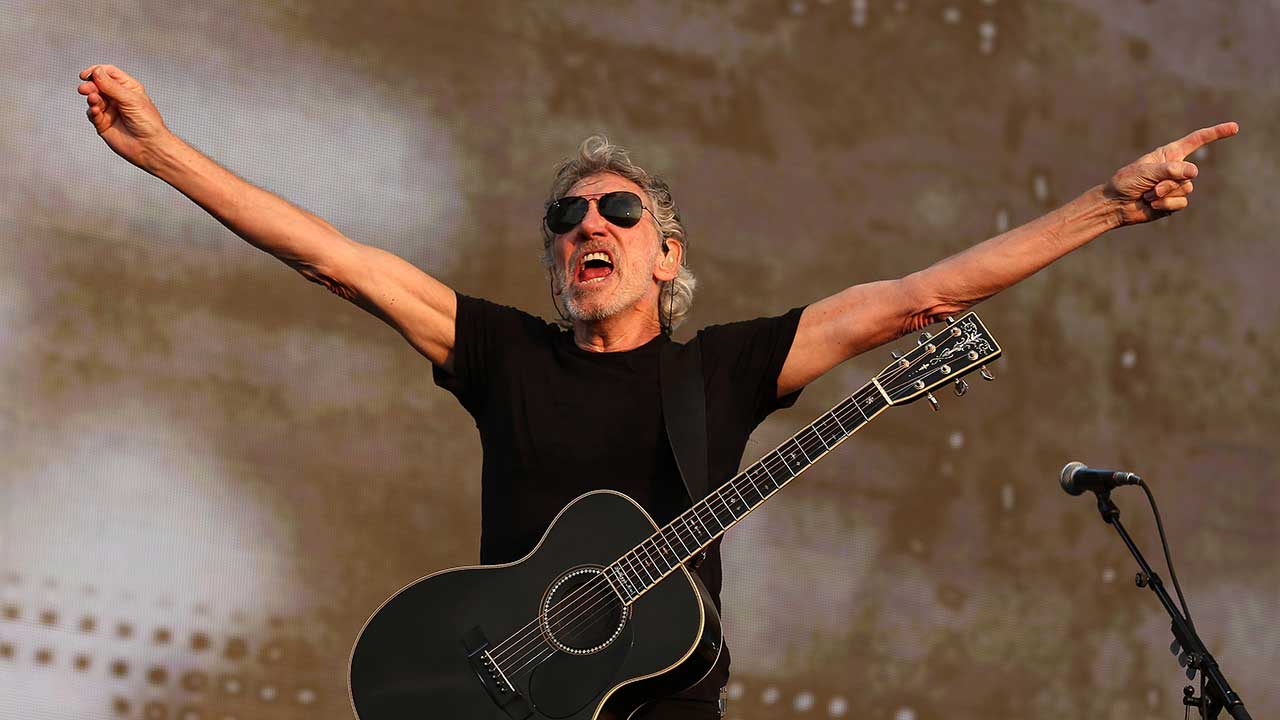

Roger Waters’ solo catalogue might have been eclipsed commercially by Pink Floyd’s, but you overlook it at your peril. Here are the 10 Waters solo tracks that every Floyd fan should own

Despite Pink Floyd’s colossal success in the 70s, the biggest-selling band on the planet could have walked down any city street unrecognised.

After the band’s rancorous split in the 80s, such anonymity was to prove costly to Roger Waters as he attempted to established his solo career. To the uninitiated he was just the bass player/singer; only Floyd fans appreciated his overwhelming contribution to the band.

During the 80s Waters looked forwards rather than backwards. His 1984 tour was dominated by an elaborate presentation of the whole of his solo album The Pros And Cons Of Hitch Hiking. The tour for Radio KAOS was an even more spectacular affair. But that tour clashed with Pink Floyd’s stadium-busting return (without him), and Waters had to face uncomfortable truths about the pulling power of a name.

His response was the gargantuan, all-star Berlin Wall bash that reclaimed his meisterwerk from his erstwhile colleagues. But for whatever reasons – mainly economic – he didn’t tour after the release of 1992’s Amused To Death, widely regarded as his finest solo album. As a result, a major opportunity for Waters to consolidate his solo identity was lost.

When he eventually returned in 1999 with the In The Flesh tour, three-quarters of the show consisted of Floyd classics. And when he played Hyde Park last year and performed the whole of Dark Side Of The Moon, there were just two solo songs in the set. With Waters’s shows this summer once again to be dominated by the performance of Dark Side Of The Moon, his solo career is in danger of being trapped on the wrong side of the wall.

Which would be a tragedy, as some of the post-Floyd music Waters has recorded is up there with some of the best he helped create with the band he co-founded almost 40 years ago.

What follows, then, are 10 Roger Waters solo tracks that every Pink Floyd fan should listen to. You won’t be disappointed. Then again, given that it’s Waters, you also won’t be amused to death.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Every Stranger’s Eyes (The Pros & Cons Of Hitch Hiking, 1984)

After the gloom that infused The Wall and The Final Cut, Every Stranger’s Eyes brings the optimism of redemption at the end of his first ‘proper’ solo album. It’s a theme he returns to frequently in his solo career.

The notion of hope through fear may be somewhat unexpected for Waters but in fact the sentiments aren’t so different from the ones he had expressed in Echoes more than a decade earlier.

It’s the song from The Pros & Cons… that Waters has continued to play live where it stands out in contrast to the lyrical cynicism of the Floyd classics. It may be simplistic, it may be hippy-ish in tone at times but Waters’s own passion gives it a positive charge.

Radio Waves (Radio KAOS, 1987)

Steeped in 80s pop production technology, Radio Waves is probably one of the most commercially calculated songs Waters has written.

For the opening track on the Radio KAOS album, he had to come up with the kind of song that would fit the playlist of the radio station that was part of the album’s concept. He also had to devise a short and effective way of introducing a complex plot and storyline.

Those who criticise the song for being “trapped in the 80s” are missing the point. The song had to be clad in the prevailing pop fashion of the time. This was 1987, and elementary post-disco beats with all the bland studio mod cons were all over the charts. In addition, part of the concept for the album involved the demise of free-form music stations like Radio KAOS and the rise of formatted, computer-programmed stations where music was played for profit rather than pleasure. So there’s an irony to Radio Waves.

No other Roger Waters album starts in such a bright and breezy manner. Grab it and be grateful.

Who Needs Information (Radio KAOS, 1987)

Inspired by an incident in 1985 when a striking miner threw a concrete block off a motorway bridge, killing a taxi driver who was taking a working miner to the pit, Waters weaves the event into the broader context of the album’s theme on this powerful rocker.

Wheelchair-bound Billy and his twin brother Benny, an out-of-work miner, go out for a night on the piss. In the early hours they’re hanging round an electrical shop when the temptation becomes too much for Benny, and he steals a cordless phone.

A little while later, heady with bravado and alcohol and bitter at the system that has left him jobless, he’s swaying on the parapet of a footbridge yelling: ‘Can you see the whites of their headlights?/Are they coming yet?’

All the while the song is gradually growing in density and power, driven by a relentless chorus. The sound gets thicker as jagged metal guitar chords and saxophones jostle for space and later on there’s even a brass section trying to get in on the act. But Waters marshals his musical resources superbly and slowly ratchets up the intensity of the song while leaving room for his vocals to cut through.

The Tide Is Turning After Live Aid (Radio KAOS, 1987)

If Radio KAOS begins in unaccustomed Waters style, the final track shows another unfamiliar trait: optimism.

The clue lies in the brackets. Although Pink Floyd did not participate in 1985’s Live Aid, Waters was deeply affected by how the event used the power of global communication as a force for good. Hence the glimmer of hope for mankind at the end of a diatribe against the abuses of power and technology.

But now there’s a chance for the future and a challenge to world leaders: ‘Now the satellite’s confused cos on Saturday night/The airwaves were full of compassion and light… I’m not saying that the battle is won/But on Saturday night all those kids in the sun/ Wrested technology’s ward from the hand of the war lords.’

As the feeling takes hold, the song’s hymnal qualities are enhanced with swathes of keyboards and choirs, boosting the melody. At the end comes the line: ‘The tide is turning, Sylvester.’ Not a fan of the Rocky movies, Waters is taking a shot at Sylvester Stallone and his portrayal of the macho violence that Waters blames for so many of the world’s ills.

Towers Of Faith (When The Wind Blows OST, 1987)

Written for the film animation of Raymond Briggs’s When The Wind Blows, Towers Of Faith appears on the soundtrack but not in the movie. Waters’s lyrics bypass the film’s theme of nuclear war and focus instead on the ivory towers built by religious and business leaders who ignore the conflicts and damage that their beliefs and actions produce.

The song attacks prophets and Popes for their blinkered intransigence and fundamentalist views There’s no mention of Islam but there’s an eerie feeling of déjà view when Waters directs his venom at the multinational corporations: ‘And in New York City the business man in his mohair suit in the World Trade Center/Puffs on his cheroot and he says: “Well I don’t care who owns the desert/My brief is with the hydrocarbons underneath”.’

Written 15 years before the events of 9⁄11, Waters’s prophecies would make Nostradamus jealous.

Perfect Sense (Amused To Death, 1992)

On the two-part Perfect Sense Waters shifts his attention from Radio KAOS to TV mayhem, where war has become a 24-hour reality show.

American sports presenter Marv Albert provides a running commentary as a submarine torpedoes an oil rig, while the crowd cheers and jeers.

Out of this glorious confusion of sounds and images emerges one of Waters’s finest choral refrains, repeated until it becomes a mantra: ‘Can’t you see/It all makes perfect sense/Expressed in dollars and cents/Pounds shillings and pence.’

Perfect Sense could rival Wish You Were Here as a crowd singalong, given the chance.

The Bravery Of Being Out Of Range (Amused To Death, 1992)

Having assembled a stellar band for Amused To Death, Waters gives them some biting rock’n’roll to play.

The Bravery Of Being Out Of Range opens with some heavy drums and a biting guitar that coalesces into a thunderous, booming riff. No need for any special effects here; Waters’s scathing sarcasm gives the song all the spice it needs.

The title of the song is loaded and self-explanatory: The “brave” include any old president of the USA, people watching war on TV in bars (‘You hit the target and win the game from bars 3000 miles away’) and the gun lobby (‘You’re at home on the range’).

All the while the girlie backing vocals are reminiscent of Floyd’s The Great Gig In The Sky from Dark Side Of The Moon.

Too Much Rope (Amused To Death, 1992)

The sentiments are straightforward and there’s scarcely a melody to speak of, but the production and added sound effects – chopping wood, sleigh bells and horses hooves passing by – combine to make Too Much Rope a soundtrack so vivid that you don’t need pictures.

Waters’s lyrics are something of a rambling monologues. He starts out in the frozen tundra, searching for gold and gazing suspiciously at his travelling companions, then you are transported to a colonial bar where some hapless soul is selling his kidneys, and then to Vietnam where an American veteran is trying to come to terms with his past.

The music shimmers as guitarists Steve Lukather and Geoff Whitehorn circle each other over some wonderfully deep bass runs, ethereal keyboards and delicate 12-string strumming.

Amused To Death (Amused To Death, 1992)

The final track on Amused To Death opens soporifically, as if waking from a deep sleep. The mournful guitar, the meaningless TV show droning on and Waters asking: ‘Doctor, doctor, what’s wrong with me? ’

Images of celebrity culture, with women as eye candy, of people huddled round TV sets, and of feeling breathless, conspire to maintain the confusion which only begins to make sense when Waters pronounces: ‘This species has amused itself to death.’

The song swells into one of Waters’s classic grandiose riffs, propelled by soaring guitars. Meanwhile, mankind is watching its own demise on TV following a nuclear disaster. While some grab the last of the luxuries left lying around – jars of caviar, a fast car – most are simply transfixed by the spectacle being played out on television.

Each Small Candle (In The Flesh, 2000)

Written in 1999 in response to the mutilation of Yugoslavia and specifically the Nato bombing of Kosovo, Each Small Candle was introduced during the extended In The Flesh world tour (it appears on the live CD/DVD) and soon became established as its encore.

The quavering keyboard sound that starts the song is reminiscent of the introduction to Sheep, from Floyd’s Animals, but the rest of the band impose a sombre mood as Waters recites a poem by a man who is scared not by torture or death but by the ‘Blind indifference of a merciless unfeeling world’.

He then tells the story of a Serbian soldier, as the music resumes it’s stately pace, leading to the chorus: ‘Each small candle/Lights a corner of the dark.’ At first it’s almost tentative, but the repeated chorus lines become more potent until the band take over with a burst of late-70s Floyd-style pomp, and a guitar solo that even David Gilmour could relate to.

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.