As he hurtles across a mini roundabout straight into the wall of a neat Wembley abode, his jangled brain considers the potentially catastrophic consequences. Obviously, he’s not going to die: mortality’s something that only ever happens to the other guy. He is, however, carrying a chemical cargo to gladden the heart of any ambitious cop.

And so, within seconds of his massive Bentley screeching to a halt in the demolished remains of the garden wall, Keith is up, out and frantically disposing of his stash. It’s at this point that he’s surprised to hear a familiar voice: “Hello Keith, how are you doing?”

It’s the Stones’ keyboard player, Nicky Hopkins – the man whose garden he’s just crashed into.

“My steaming Bentley’s in the middle of their rose bushes,” remembers Keith, 38 years down the line, “I’m tossing capsules, because I can hear the sirens already and suddenly there’s Nicky saying: ‘Come inside and have a cup of tea while we wait for the policemen.’ I knew then that God was on my side.”

And not for the first – or indeed last – time. Keith’s crashed his car on so many occasions that even he can’t be sure just how many. “You cover a lot of miles; you’re bound to bump into things,” he shrugs.

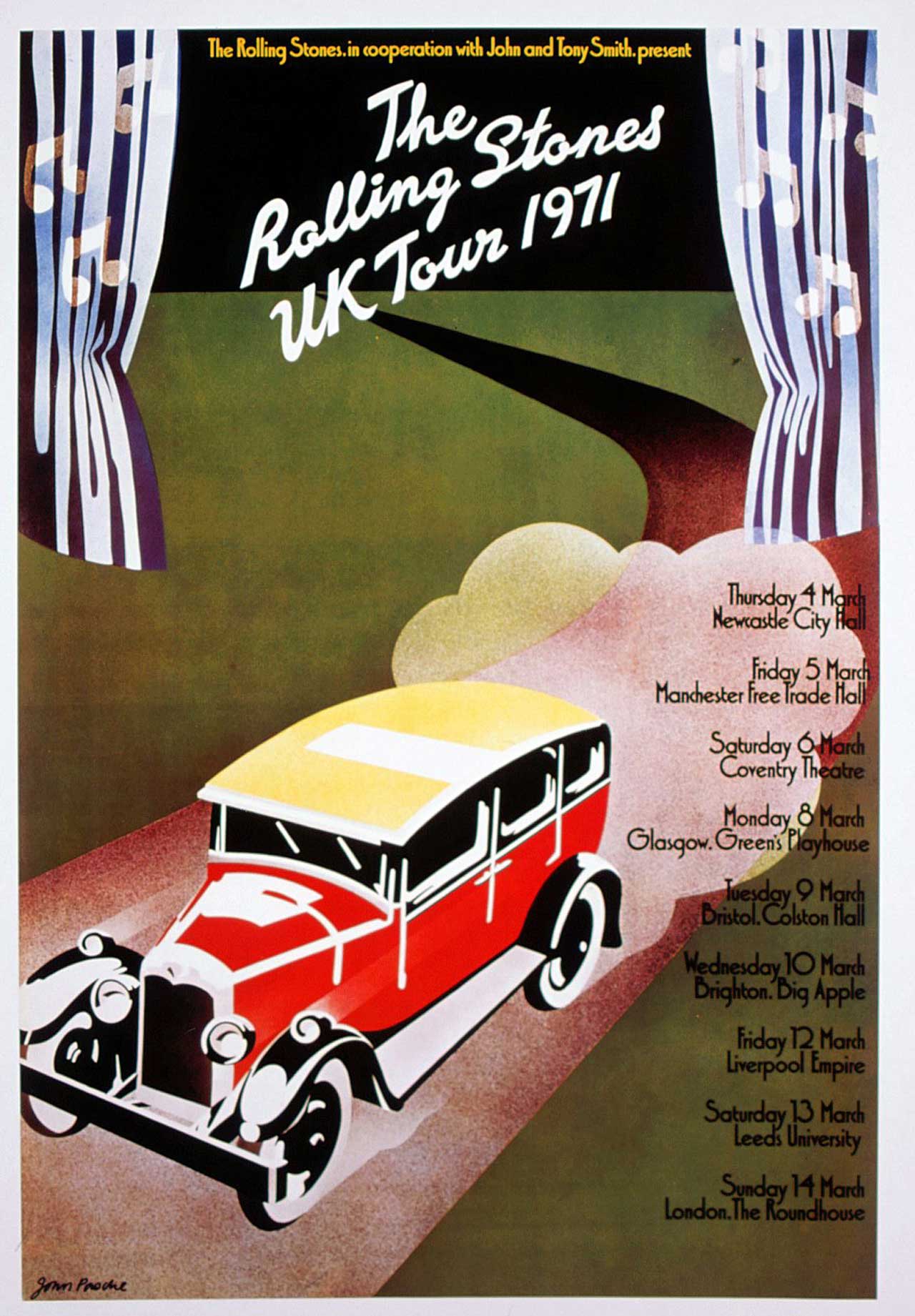

“Anyway, we got out of that one: my farewell to England basically, it was only about a week later that we moved out to Nellcôte.”

To say that his reputation precedes him is an immeasurable understatement. The nascent art of rock journalism found its vocabulary while grasping for superlatives to describe the man we’re about to meet. As rock’n’roll peaked as both a commercial and countercultural phenomenon in the late 60s and early 70s, Keith Richards was the yardstick by which all others were measured.

He was the human riff, the diseased crow-alike that, if he moved next door to you your lawn wouldn’t wait around to die, it’d move to a better neighbourhood. Gypsy, pirate, Glimmer Twin, fugitive, Jack Daniel’s-driven insect man from the Planet Cool. One week he was the world’s most elegantly wasted human being, the next its most stylishly dissipated. More often than not he was simply ‘Rock’n’roll Himself’. But that was then, and while we’re ostensibly here in New York City’s exquisite Mercer Hotel to revisit those halcyon days when the Rolling Stones, officially the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world, were recording their ultimate masterpiece Exile On Main St, we’re also here to check out Keith as he is now.

We’re all aware of the reputation, so what of the reality? With his eighth decade looming, how is ‘Rock’n’roll Himself’ holding up? Keith is a caricature made up of certain familiar elements: the rolling gait is surprisingly unmistakable, as are the brown eyes that flash from humorous warmth to soul-freezing danger in a fraction less than a wink. Then there’s the single most instantly recognisable suite of jewellery in rock: the handcuff bracelet (a reminder to the one-time jailbird that freedom cannot always be taken for granted) and skull ring (the great leveller; as Keith himself puts it: “Skulls remind us that underneath it all, we are all the same”).

Keith veritably bounces into the room. He’s carrying an opaque paper cup that punctuates his every pronouncement with emphatic clunks of ice. It gives every indication of being a soft drink, but it’s clearly not. It’s an incongruous imposter with a bendy straw. It doesn’t fit. The absence of a characteristic whisky tumbler gives the impression that Keith would rather not advertise the fact that he’s drinking – would rather give the impression that he’s ‘just saying no’.

There’s nothing surreptitious about his continuing allegiance to the fags though. Yet even after all these years his ashtray skills remain rudimentary. As his arms flail emphatically the fallout’s inescapable. As we settle down to spool back through time to 1971, the official Rolling Stones logo Zippo lighter sparks up yet another gasper and seemingly refuelled by an invigorating lungful of fresh nicotine, Keith’s away.

“It was called Exile because we were basically booted out of England. It was either that or sweep the streets.”

It might sound dramatic, but the Rolling Stones were in dire financial straits at the dawn of the 1970s. Their erstwhile manager, Allen Klein, with whom they were currently in ongoing litigation, had misled them into believing that they were far wealthier than they actually were. Consequently, they owed a fortune to the Inland Revenue and, with top rate taxation under the Labour Government running at 93 per cent, were unable to clear enough earnings to pay their back taxes. Keith, then being unsuccessfully busted on a regular basis, took this high rate of tax personally. It seemed like yet another way for the establishment to persecute the Stones.

“They couldn’t get you in jail, so they put the economics on you, the old double whammy,” he says. “So the feeling within the band was we’ve got to show them we’re made of sterner stuff and prove you couldn’t break the Stones just by kicking them out of England. We all looked at each other and said, ‘Okay, we’ll do it on the lam’.”

So the band and their families reluctantly decamped for the South of France. “Well, if it’s going to be France, it’s got to be the Riviera, pal.” Somerset Maugham liked to call it ‘a sunny place for shady people’ – it just seemed to fit. Keith moved into Villa Nellcôte, Villefranche-sur-mer. During the war Nellcôte had served as the Gestapo headquarters (there were still swastikas embossed onto the air vents) and as no other suitable recording space could be found in the area, the band chose to record in its basement using the mobile recording studio that they’d previously rented out to the BBC to record sporting events.

“Finally this truck came in handy: a great control room on wheels, but there was a lot of slap-dash improvising because we’d never recorded outside of a studio before and this basement was… well, I can smell it now: every time I look at that cover, I can pick up a certain damp, oily, dusty flavour.”

“A lot of the songs started off with an idea. Mick’s playing harp, you join in and before you knew it you had a track in the making and an idea working. It might not be the finished track; you’re not trying to force it. As my father used to say:

‘Keith, there’s a difference between scratching your ass and tearing it to bits’.”

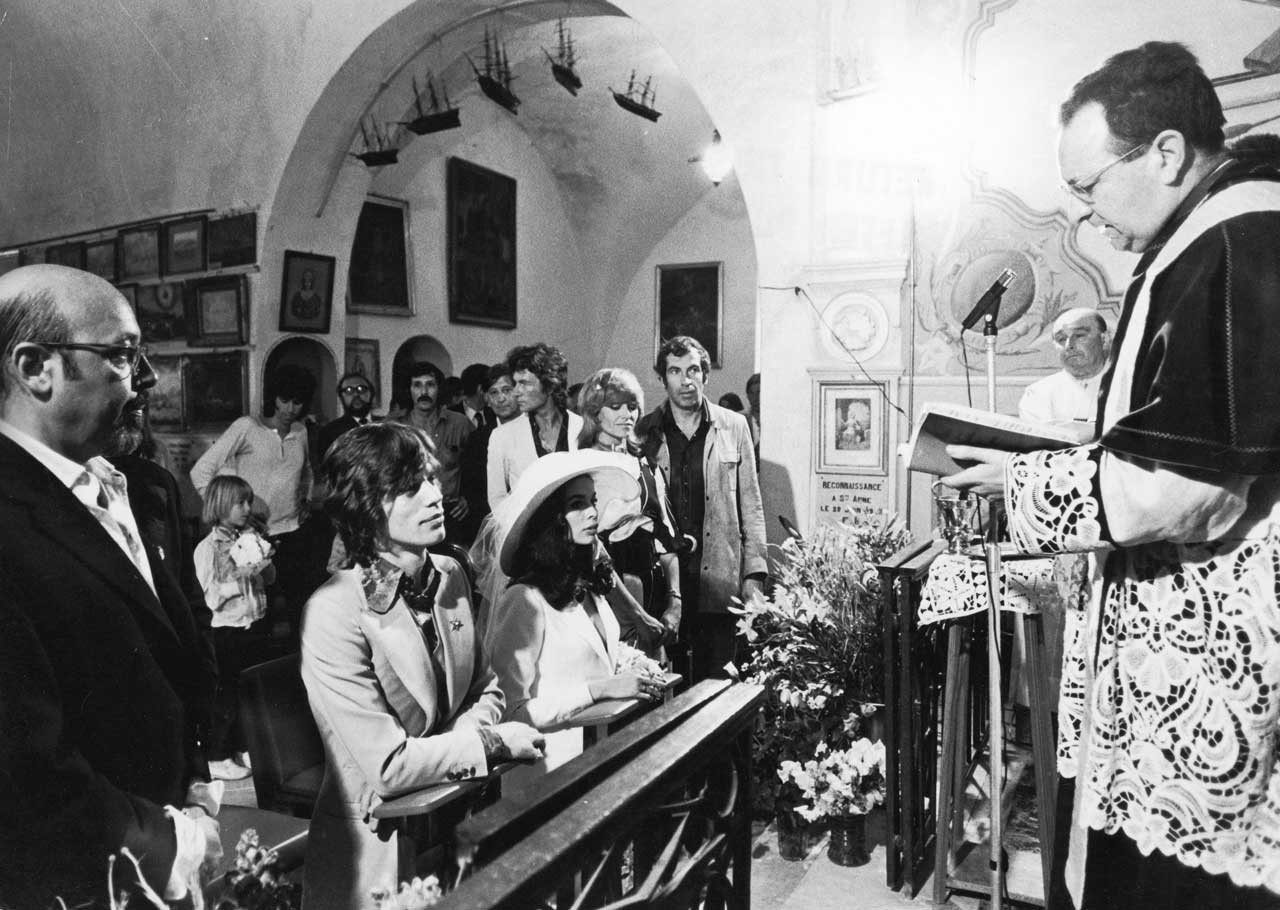

Mick meanwhile was often absent from the sessions, attending to his pregnant wife Bianca who he’d married a month previously (“It didn’t last long,” says Keith. “I knew it wouldn’t”).

Drugs-wise, when the Stones first arrived at Nellcôte, “Nobody was particularly dirty,” says Richards, “but I was probably the dirtiest of the lot… but what else is new?”

Keith’s mood changes immediately and he flashes a glance that can freeze the blood in your veins. Ian McLagan (former Faces keyboard player and occasional Stones sideman) once told me that “Keith always had a .38 with him.” And how, after his former confidant Spanish Tony Sanchez betrayed his trust by writing his fix ‘n’ tell Up And Down With The Rolling Stones memoir, Keith didn’t threaten him verbally, he simply showed him a revolver. A simple reminder: ‘what goes around comes around’.

But that look, where his right, Kohl-smudged eye widens slightly, his left narrows and his whole body pivots forward shoulder first, is the physical equivalent of producing a concealed weapon.

Say hello to His Satanic Majesty. Now here’s the Keef of legend…

“I’m off and I’m on,” he leers. “It’s no big deal to me. Cold turkey? I spit on it. Oh, agony… It’s no fun, but… At that time I was no more out of it than anybody else. Charlie was hitting the Cognac like a motherfucker, Mick loves his wine – but that didn’t even occur to us. People did what they wanted to do. It was like, ‘Are you going to go into that room and come up with something? If you do that I don’t give a damn if you’re snorting God.’ What fuel you’re running on is immaterial, as long as you come up with the goods.”

While Villa Nellcôte had been temporarily occupied by the Rolling Stones and an extended entourage of guests, n’er-do-wells and hangers-on for recording and partying purposes, it was also Keith Richards’ home.

Consequently, Keith would occasionally disappear upstairs for hours on end, sometimes at crucial points during recording. Not to conjure up Lucifer over exotic narcotics with Anita (who, it should be noted, the majority of the party were genuinely terrified of), but to set about the task of putting his 18-month old son, Marlon, to bed in spite of the ongoing tumult below.“Kids can get used to anything,” he shrugs. But it’s a pretty strange arrangement…

“Go tell it to the gypsies,” he says. “What’s so weird about it? What am I going to do? Send him to a prep school in a silly little uniform? This is what dad does. He was my navigator. At five years old he could read a map – to tell me when we’re getting near the border, because I’ve got to dump the shit, you know what I mean?”

Ah yes: ‘You know what I mean?’ Keith’s colourful discourse is liberally peppered with these five words, though they’ve long since evolved into a single almost unintelligible ejaculation – not unlike a lorry changing gear – that punctuates his every anecdote. Like the one about Nellcôte’s French chef…

“Big, fat Jacques, yeah, he was a dealer too. Every Thursday he went to Marseille to pick up… [he checks himself and laughs: a fruity death rattle]. He also blew up the kitchen… some of this is cartoon shit, you know what I mean?”

Or Keith’s only – as he remembers it – run-in with Monsieur Plod Le Gendarme: “I was with Spanish Tony in Beaulieu, the next town along from Villefranche, and we got pulled over by the harbour master and his bosun. Anyway, they took us into this office. They were big guys and Spanish Tony smells trouble and says: ‘Get ready. They’re gonna do us.’ I said: ‘Right, I’ll watch your back’ and Tony went into action. Talk about Bruce Lee, you know what I mean? Tony leapt onto this table, picked up a chair, and put the both of them down. Within two seconds these guys are groaning and going ‘Zut alors!’ and all this shit. ‘Mon Dieu!’ ‘Sacre bleu,’ and other curses in French. I stood on one while Tony finished off the other and we left.”

End of story? Not quite… “A week later there’s a knock at the door and there’s the Gendarme with the lovely kepi, all smiles, with some papers. They’d filed charges of course, and French courts are weird, you go through this charging structure and it’s a totally different system, you’re guilty until you’re proven innocent over there, which is an interesting twist, you know what I mean? Not that it makes much difference in the long run, I’ve found. Anyway, it all drifted away, but that was my only brush with the constabulary in France.”

Do such things usually drift away so easily? Previous reports of the incident suggest that a few signed Stones albums helped to smooth things out for Keith and that Spanish Tony, as the man ultimately wielding the chair, was fined $12,000 in his absence (which Keith paid). Bill Wyman remembers Keith having another brush with the Gendarmerie after his car was in collision (what are the chances?) with some Italian tourists, but hey, who’s counting?

Anyway, Keith’s side-tracking us: back to Exile…

Part of the magic of Exile On Main St stemmed from the working relationship that had developed between Keith and fellow guitarist Mick Taylor.

“Brian [Jones] and I would swap roles. There was no defined line between lead and rhythm guitar, but with Mick’s style I had to readjust the shape of the band and it was beautifully lyrical. He was a lovely lead player. I loved playing with Mick Taylor. I was probably more shocked than anybody else when he decided he was going to leave. ‘What, are you crazy? What d’you think you’re gonna do, pal?’ And sure enough: nothing.”

He clearly thought that he had to match your lifestyle which, obviously, not everybody can.

“I don’t know if he thought he had to. He was just sort of drawn into it. It’s like a vortex… ah…hur… hur… hur… [the most evil laugh of the day so far: like an extended, gasping death rattle that never quite touches the sides]. Don’t get too close to the whirlpool, you know what I mean?”

One of the most significant visitors to Nellcôte during the summer was Gram Parsons: a kindred spirit of Keith’s who harboured hopes that the pair would record a country album together.

“There was an idea – but nothing in concrete,” says Keith. “We’d all become very good friends, especially myself and Gram, and I think Mick [Jagger] looked a little bit askance at it. Mick doesn’t like me to have anybody around me…

And at that time, Mick’s regular response to: ‘Hey Mick, this is a mate of mine,’ was [adopts sniffy, unimpressed Mick voice] ‘Hmm, who are you?’ [a laugh that starts out as emphysema and ends up as a knackered motorbike clearing its carburettor]. You could say either he was being protective or that there was a streak of jealousy there, you know what I mean? I’d say yes to both.”

And at this point it seemed that the unwritten law was that no members of the Rolling Stones made solo albums. “Yeah, that would have been an absolute no-no at that time. That would mean that you weren’t happy with the band. That came later, Mick started that.”

Would you have ever made a solo album if that hadn’t happened?

“No, of course not… I’m glad I did though, I’m glad Mick forced me to do that because I prefer Talk Is Cheap and Main Offender to She’s The Boss [a satisfied chuckle as the ice clanks]. Mick thought it would be easy and found that it wasn’t. He didn’t quite cotton onto the fact that, yeah he’s a good singer, but the important thing was… the Stones. Mick, given his enormous ego, which every lead singer needs, thought: ‘Ah, they’re just sidemen’… Which led to World War III.”

Mick’s always seemed to have something of an ambivalent attitude to Exile… “Well, that’s Mick. Mick’s never gonna tell you the truth [long pause, pops the old right eyeball for emphasis]. Who are you to get the truth out of him? To the point where he doesn’t know what the truth is, or even if there is such a thing as the truth. There are a whole lot of conflicting emotions and ideas there… You’re just the damn singer, man. But what do you expect of guys that have been together for 40-odd years? The whole thing works off of certain abrasions…

Pointless fighting is useless, but if certain things come out of conflict, it’s worth the fight.”

It’s the grit that makes the pearl. “Exactly… and God help the oyster.”

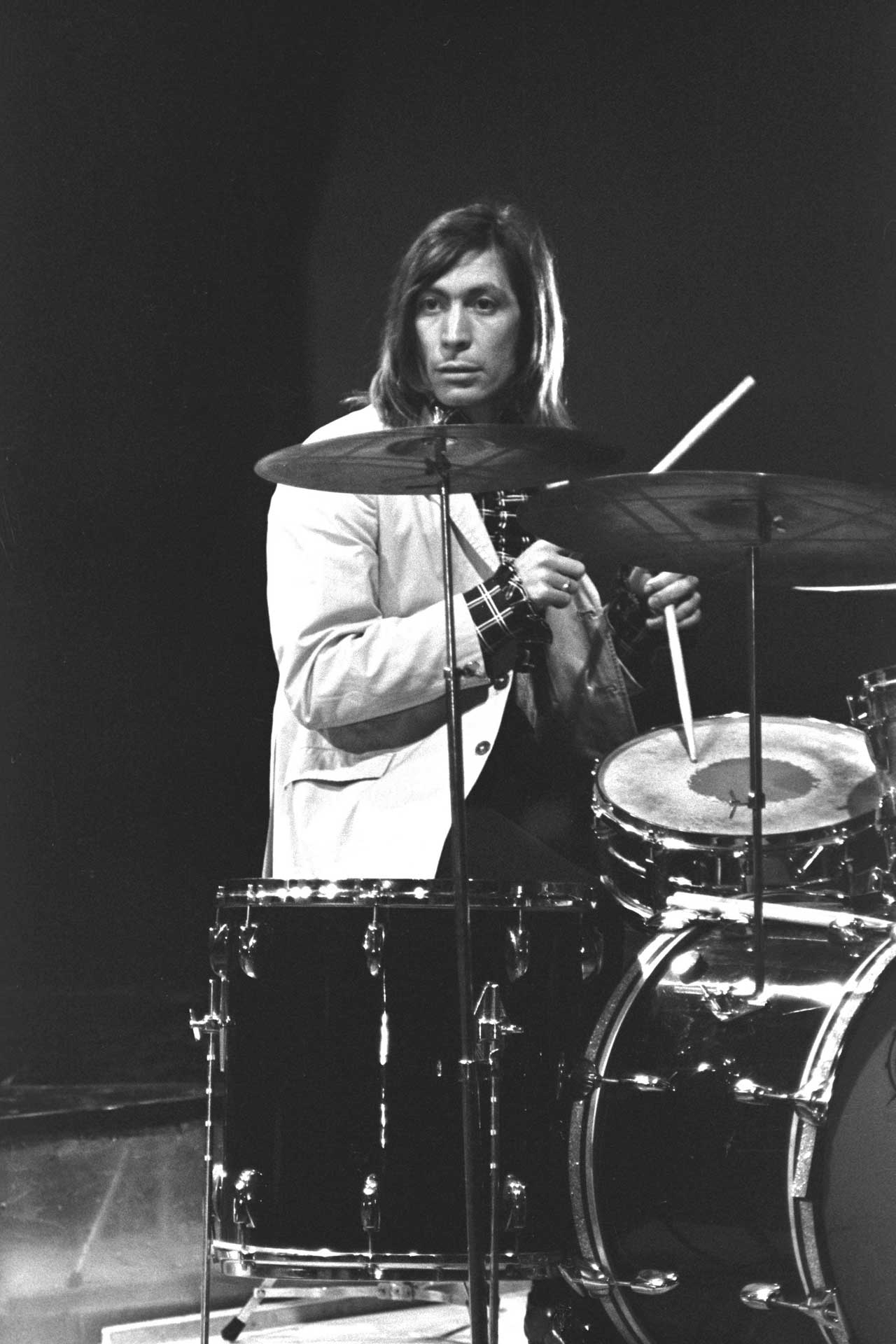

“You’ve seen Keith?” Charlie Watts, the world’s most effortlessly dapper human being, sets aside his second and – fully engaged, with eyebrows raised – enquires: “How was he? Well?”

He smiles broadly at the news that Keith is, if anything, very well. In fact, the first adjective that springs to mind to describe his state of health is ‘bouncy’. And, with a degree of understatement that surely only he could muster, chuckles: “He’s funny, he is.”

Charlie Watts, immaculately attired in a gangster-cut, navy blue, broadly pin-striped suit, Cambridge blue, round-collared shirt and Oxford blue, Windsor-knotted tie (complete with pin, naturally), cuts quite a dash.

Keith clearly thinks of Charlie what everybody else thinks of Keith – that he’s the heart and soul of the Rolling Stones personified: “I can never say enough about Charlie Watts,” Keith had told me a couple of weeks before. “It was the luckiest day for this band and myself personally the day that we got to play with such a drummer. With Charlie I never have to worry where the backbeat is. I mean, hey – if you’re talking about rock’n’roll, the drummer is the hidden hero basically.”

So what was it that Charlie saw in the fledgling Stones that finally coerced him to join? “A job,” says Charlie, somewhat unromantically. There’s no old flannel here, not a single scrap of diplomacy, his honesty is disarming, his openness total.

“I was in about three bands when I joined them. It was like whoever came up with somewhere to play, you’d go and play.”

Charlie was distinctly unimpressed with the band’s decision to move to France in ’71. “I was told I had to move and I said ‘No, I’m not’.”

My suggestion that, as a non-songwriter his need to escape British taxation was probably not as great as that of Mick and Keith (who, then as now, commanded the lion’s share of the Stones’ earnings) is met with a withering: “It had nothing to do with song-writing, I don’t know where you’ve dreamed that up.”

Anyway, once it was explained to Charlie that financially a move to France was the only way forward for the band, he eventually capitulated. Did it ever occur to him that life outside of the Stones – who were not only being forced out of the country by taxation but were also being constantly hounded by the forces of law and order – might have been simpler?

“It never crossed my mind. Keith was really getting the hassle, but then Keith was a stronger drug man than anyone. I wasn’t into drugs… I mean, I smoked, but everyone I admired was either a junkie or an alcoholic. It’s not something to be proud of, but it’s true. That world seemed very glamorous to me. It was the world that I wanted to be in from the age of 13. I didn’t want to be a junkie personally, but that’s the world I loved. I used to go to the all-nighters at The Flamingo Club [in London’s Wardour Street]. And, though I didn’t know it at the time, half the people in there were junkies. That’s where I first met Ginger Baker… So Keith suddenly taking a liking to it wasn’t a shock to me at all.”

- The Rolling Stones announce new album Blue & Lonesome

- The Rolling Stones – 50 Years Of Rock'n'roll

- Keith Richards' Guide To Life

- Rolling Stones albums ranked from worst to best

Charlie has a vinyl copy of Exile On Main St open on the table in front of him, so it should be relatively easy to steer him back to the subject at hand. But as our tête-à-tête takes place in Dean Street, Soho, a series of stone’s throws from The Flamingo, Old Compton Street’s 2i’s Coffee Bar and Archer Street (where as a jobbing jazz drummer pre-Stones Charlie would often tout for work), he’s easily side-tracked.

Keith had told me that, with Charlie and Bill Wyman living an hour’s drive away from Nellcôte, a lot of Exile’s recordings were made in their absence – with (in the case of Happy) producer Jimmy Miller on drums and Keith doubling on bass. I put this snippet of insider information to Charlie.

“We played together on Happy,” he says. Oh. According to Charlie, rather than being an hour’s drive away, he was actually living at Nellcôte at the time.

Keith Richards? Memory lapse? With his reputation?

Whatever, Charlie’s extremely generous in his praise of Jimmy Miller both as a producer and as a drummer: “I loved Jimmy Miller,” he says.

“I thought he was the best producer we ever had. Jimmy was a hands-on type of guy. When we played he could never keep still, so he’d always be banging something; a drum or a cow bell [that’s him at the start of Honky Tonk Women]. But Jimmy was lucky; he had a good band to record back then.”

Ah yes, now we’re getting somewhere.

So how was working with Bill Plummer? “Who’s Bill Plummer?”

He played stand-up bass on Rip This Joint and All Down The Line.

“What, on here?” Charlie asks, gesturing toward Exile’s cover…

Anyway, moving on. Were you surprised when Mick announced that he was to marry Bianca?

“No.”

Really? He’d always seemed to be very non-conformist up to that point and then suddenly, out of the blue, he’s the marrying kind?

“Mick is a very middle-class boy from Dartford,” says Charlie. “Keith is, and was always, much more outside of everything than Mick. Mick was never what he wrote: he was never Satanic Majesties and he was never a Street Fighting Man, but he wrote bloody good songs that created this persona. So for him to marry… It’s what people did. I don’t think it’s ever suited him though. He’s never really liked it… But he seems very, very happy at the moment.”

While Charlie doesn’t mind talking about his summer in Exile he’d much rather wax lyrical about the drummers he admired in his youth (Phil Seaman, Earl Phillips), but if he absolutely has to talk about the Stones, this is the period – and indeed line-up – that he remembers with the greatest fondness.

“I don’t think Keith is as enamoured of Mick Taylor as I was. It was like having Carlos Santana in the band. For me it was wonderful. Mick would go off, and you’d go off with him. It was like the jazz thing, really. He gave terrific beauty to the tracks he played on: Loving Cup was a good one. For me, that’s always been our best and most productive period: that Exile era.”

“What came out of us on Exile,” says Keith Richards in a blur of waving arms, jewellery and fag ash, “was what we’d learnt playing America for eight years. We were working an awful lot in America, and learning first hand what we’d only learnt before from records. Just soaking up American culture and realising that, you know… they love an Englishman, if you play it right.”

Keith’s been playing it right for four decades now: the English rapscallion; exiled from his homeland; trotting the globe; the quintessential lovable rogue; Terry-Thomas with a skull ring.

“Yeah right… ‘You bounder!’ ‘Blast!’ all of that.” Keith grins, adopting the requisite accent.

It’s not much of a stretch, to be honest. Beneath the superficial damage wrought by miscellaneous recreational toxins, Keith’s customary enunciation is more that of a charm-laden, public school rotter than a Dartford-encumbered, art school drop-out.

The Keef of legend – the Keef that sells magazines – was partly created by a pre-punk 1970s music press in search of an anti- establishment figurehead. While Keith was occasionally vilified by the red-top tabloids, rock journalism’s finest were regularly reinventing him as ‘the world’s most elegantly wasted human being’ while crediting him with a degree of infamy and indulgence that could only ever have accorded him iconic status. He was the Patron Saint of Rock Misbehaviour; the Minister for Unhealth. He sold an awful lot of newspapers.

“They fed us the material and we played up to it, basically,” he admits. “You wanna meet Keith Richards? Which Keith Richards would you like to meet?”

Whenever Keith makes a joke it’s reported as fact because it makes for good copy and compounds the myth of Keef: Marlon’s first words being ‘room service’, the Swiss blood changes, the snorting of the ashes [Keith greets each of these self-seeded myths with a fruity snigger].

“I enjoy finding out what other people find interesting because from the inside out it’s all very amusing.”

You’re not a serial litigant: the likes of Spanish Tony publish their allegations without fear of a court case. Do you enjoy the notoriety that’s been thrust upon you?

“As long as they talk about us who gives a shit? You know what I me-ahh-ahh-nnng-ah…” [He drifts off into a bit of a boggle-eyed yodel – ice clanks, ash flies, arms wave – it’s classic Keith.]

With Keith long considered the essence of rock’n’roll distilled, there’s more than a frisson of déjà vu when you finally meet the real thing: I’ve never met a band that didn’t include at least one counterfeit Keef. But what of the genuine article; who is the real Keith Richards?

“Hey, I’m a family man,” Keith soberly asserts, “And I have been since I was 26. I know people always like to make you all very cut and dried and simple: ‘Oh, he’s a fucking maniac’. Yanarrrrrrrrrrrrr rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr [an outboard motor-styled ‘you- know-what-I-mean’]? And I can be, when I have the time for it, but I’m also growing up. I pace myself. I love my families. I have several – extended.

And they all love each other. I’m extremely blessed with my ladies who all, thank God, get along [raps the table three times]. Even I couldn’t be that kind of Keith Richards all the time.

“When I’m at home I do as I’m told: ‘Yes, darling, no, darling’, like any other guy. I avoid conflict as much as possible, especially domestically, but at the same time I know there’s a streak in me that given the opportunity will show you what Keith Richards can do [boggles the eye, lurches piratically, clanks, pouts and… relaxes]. But I feel no compulsion.

“I’m not a Keith Moon, who felt he had to top himself every time until he finally did. I’m not a maniac. But when I want a good time, I have one. And I take people with me, because then I find out what I actually did. There are a lot of things that I’ve done that even I wouldn’t believe, except I’ve got 59 witnesses, and you can’t argue with numbers.”

Do you still feel, if indeed you ever have, indestructible?

“Not quite, but almost. I’ve never felt any compulsion to prove it. I never went for this image. An image is like a ball and chain – it’s always there and you’re dragging it behind you, and people, including myself, are more complicated than that. I can be a real pussycat, hurhurhurhurhur. I’ve never felt driven to live up to this image that they’ve made of me. That’s a mug’s game, a sucker shot. But I don’t mind using it occasionally… especially if I want to get a reservation.”

As we wind down our summit, I reveal to Keith that my Christmas celebrations always commence on his birthday, December the 18th: Keithmas Day.

“It’s a real good date,” says Sagittarius Keith, who was 66 last Keithmas. “You can’t go wrong: half man, half horse and a licence to shit in the street.”

I always open my Christmas presents to the sound of Ronnie Spector singing Frosty The Snowman, what about you? I venture, in the hope that Keith will reveal a little more of himself.

“I’ve done several things with Ronnie, very few of them to do with Frosty The Snowman.” He leers suggestively before quickly throttling back from boggle-eyed lechery to silk-cravat suavity. “She’s a very good friend of mine, lives not very far way from me up in Connecticut. A great girl, and in her day… shit… I’ve been blessed.”

And with that Rock’n’roll Himself tips his fedora, clanks his ice, sparks his Zippo and is gone.

He’s the best Keith Richards I’ve ever met, and there’s been a few.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 145.