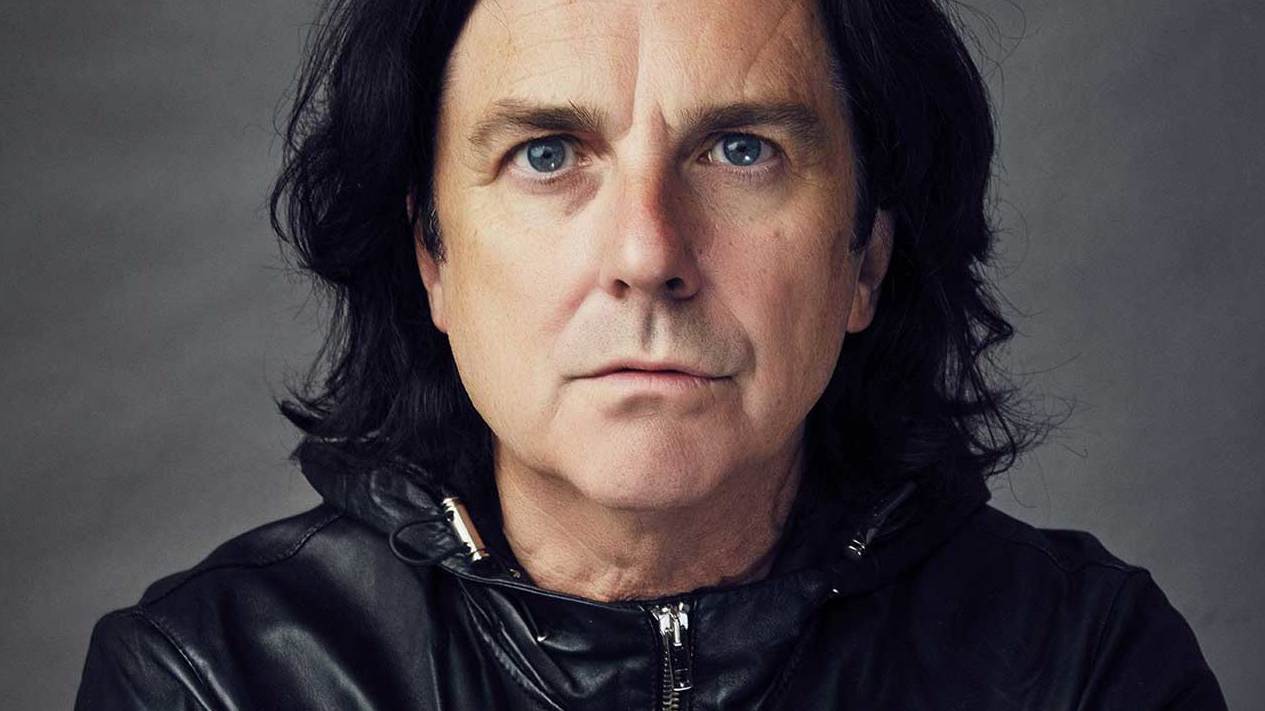

Steve Hogarth is one of the few singers – Bernard Sumner and David Gilmour would be two others – who know what it’s like to take over from a near-mythical frontman. He’s not without hubris – he tells Classic Rock about the Steve H doll currently doing the rounds among fans, complete with trademark black hair, white shirt and long black coat – but it’s tempered with humour and a self-debunking streak. He becomes heated when discussing his lyrics for FEAR, but then they are uncannily prescient. From his home near Silverstone, he considers the band dynamic that he had to negotiate when he joined in 1989.

Has there been a lot to forgive in this band?

There’s always something. The creative process will set you against one another. The potential for differences of opinion is colossal. You’ve got to employ a lot of tact and try not to take something deeply personal to you too personally. Mark and I are very passionate so we go head-to-head a lot. Then again, Rothers is the most stubborn man I’ve come across in my life.

The new album is very current, with its references to ‘leavers’ and ‘remainers’ and songs filled with a sense of impending doom.

I coined the terms ‘leavers’ and ‘remainers’ about five years ago, and I finished a lot of the lyrics three years back. I’ve been waiting for the band to finish the music. It was almost like I had a premonition – it’s spooky reading the lyrics with my July 2016 head on, and how much they resonate with what’s happened. It was all there a long time before the album was finished.

How apocalyptic a landscape are you envisioning on the album?

I don’t think I was envisioning a landscape or a worst case. I was talking about how I feel about what I see around me and also how I feel about this thing I can’t quite put into words about this approaching storm. I’m saying I’m becoming harder to live with because you can’t see into my head, because if you could, you’d understand why I don’t sleep at night.

Marillion were reviled as the antithesis of punk, but the level of anger on the album is actually quite punk.

Well, it’s a protest album. I’d like to think a bit more thought went into the lyrics than a lot of punk ones. ‘God save the queen/The fascist regime’ isn’t necessarily something that’s had a lot of thought put into it.

Surely it takes a smart mind to come up with a pithy slogan that endures for forty years?

Well, yeah, top marks to Johnny [Rotten] for that, then.

Shouldn’t rock lyrics be pithy slogans that can be reduced to wall graffiti?

They should be true. What’s the point of a slogan if it’s just bollocks? I’d rather truth that isn’t catchy than catchy fiction.

How do the Fish and H eras of Marillion differ?

I think I’m more limp-wristed than Derek [Dick]. People often say to me, ‘What kind of music do you make?” and I say, “If Radiohead and Pink Floyd had a baby that was in touch with its feminine side…”

How upset do you get by websites such as the one that asked if you’d destroyed Marillion?

I think if I was to read it, it would probably upset me. I’m sure you can find ten people to make a good argument for that, and I’m sure you could find ten people who could make a good argument for Marillion not being any good till I showed up.

Did you feel the need to ‘diva it up’ when you joined, to try to match Fish?

I’m a natural diva anyway. Always was, even in my first band, The Europeans. But I can tell you, hand on heart, I’ve never ripped Fish off or had Fish anywhere in my consciousness whenever I made any decisions about what I’m going to do on or off stage. To be honest, I never ever think about Derek William Dick, apart from when I do interviews. He really could never have existed.

- Living Colour are angry. Marillion are angry. Where are the angry young bands?

- Marillion - (Fuck Everyone And Run) F E A R album review

- The Marillion Quiz

- Pledge Pioneers: How Marillion invented crowdfunding

You’re very different from the other four. Has that made it work?

Maybe. Maybe there’s tension there. If I was more like the other four, we might be a bit whiter and a bit duller. I’d like to feel that I brought a black influence to this band. We’re still one of the whitest bands in the world, but not quite as white as Genesis or Pink Floyd.

It hasn’t been easy for Marillion, has it?

Most bands exist in a permanent state of, “Oh my God, it’s all about to fall apart!” Or, “Oh shit, now so-and-so’s got a smack addiction, or this bloke’s hanged himself.” Look at The Pretenders, for fuck’s sake. Ride that train and come out of it in one piece. I think there’s something inherent in being in a band that attracts fairly colourful characters who are not gonna have straightforward lives.

But there’s no one in the band as extreme as, say, an Ian Curtis, which presumably is why you’re all still here?

Yeah. There’s one or two very bright people in Marillion that, when our backs were to the wall, went, “We’ll embrace the internet. We’ll get everybody to pay for this next album before we’ve recorded it.” Whenever the record label lost interest, I’d get hysterical, whereas there are characters in this band who go, “We can do this.”

So without you they might have lacked an edge, but without them you might have gone off the rails?

Who’s to say? But certainly without me they’d have sounded a lot less like me.

This interview is taken from Classic Rock 228, which features interviews with every member of Marillion, and is available now to TeamRock+ subscribers.

The rise and rise of Marillion – the band that refuses to die