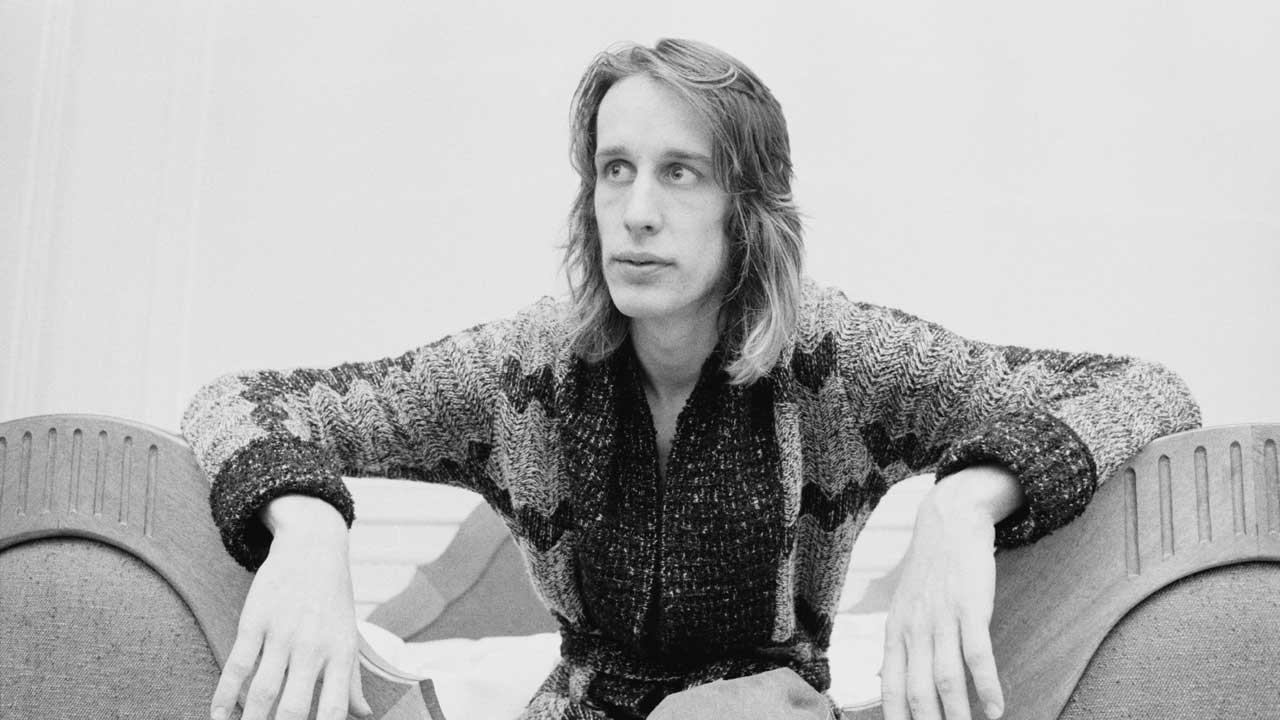

As well as being part of the title of Todd Rundgren’s classic album from 1973, A True Star is also a fitting description of the multi-talented musician/producer/ cyber voyager who has been a potent force in popular music since his eviscerating debut single Open My Eyes with his proto-psychedelic garage rockers The Nazz in 1968.

Since then Rundgren has worked with a dazzling array of bands, and achieved recognition as an artist with a series of critically acclaimed solo albums.

Here he shares some of his moments and insights from more than 40 years in music, which include some spiky exchanges with John Lennon, experiences with a drunk and sober Ringo Starr, the weird, formative years of Sparks, the insanity of the New York Dolls and the walk in the park that was his gig with Grand Funk Railroad.

John Lennon

I met John Lennon in a place called the Rainbow in Los Angeles during his carousing days with Harry Nilsson. He was sitting in a booth and someone introduced me to him. I said hi but had no conversation; I wasn’t loaded enough. That was the only face-to-face experience I had with him. But there was this infamous exchange we had through a British music paper [Melody Maker].

Someone interviewed me when I was in England, and I’m not exactly sure how John’s name came up but the context was to do with his credibility as a revolutionary. John’s antics were fairly well-publicised at the time. He was going out every night and getting drunk, and there was one particular incident where he got into an altercation with a waitress and apparently was wearing a Kotex [tampon] on his head and acting somewhat boorish.

My opinion at the time was that if you’re going to encourage people to change the world you have to have a certain amount of personal credibility, and if you start going backwards and abusing women when ostensibly you are supposed to be a feminist, it’s time to either be just what you are or drop the revolutionary shtick and clean up your act.

So this started a whole faux conflict between us. His take on it – as his take was on just about everything in those days because he and Yoko were involved in this primal scream therapy which had gotten into his music – was that he attributed my commentary down to some issues I might be having with my father. Anything that happened at that time John attributed down to some infantile issues.

Apparently after he was assassinated the police found of copy of one of my albums in the hotel Mark Chapman was staying at. I never had any contact with him and I don’t believe that there’s any evidence that the little spat me and John had any effect on Mark Chapman at all. I’m not even sure he knew about it.

Sparks

At the time I worked with them they were this weird band from LA who were called Halfnelson. While they must have had some commercial influences on their first album, it was one of the strangest projects I’ve been involved in.

Essentially the core of the band was two pairs of brothers – the Maels and Mankeys – and another guy [Harvey Feinstein on drums]. There seemed to be a lack of focus in the group when I was working with them. They wanted to produce this strange music. The Mael brothers had this highly developed image thing going but it seemed the rest of the band was more committed to playing.

The stuff they had been writing up until then was way out of the mainstream, and they wanted to become a little more commercial. It was obvious that Ron [Mael] was doing this kind of Chaplin-esque thing; he was like a silent movie, and he never said anything.

Ringo Starr

Ringo was the most approachable of all of the Beatles. I have met each of the band in turn. If you grew up on A Hard Day’s Night and Help! and watched The Beatles’ antics, to actually meet them in person was often a let-down. For instance, Paul McCartney was an unusually dour person and John was totally drunk and inanimate. George I met very briefly when I was producing a Badfinger album.

You expected cleverness and a happy-go-lucky demeanour because of the image they projected up until the point they broke up. The only one who seemed to have recovered from any of the effects of that was Ringo. He did the music for fun. He didn’t feel that there was some burden to it, he just liked to play. Any opportunity to sing was fine but I never saw him having any pretence that he was building some giant musical legacy.

My experience with him spans quite a few years. The first time we worked together was for a Jerry Lewis telethon in the late 70s in Las Vegas. Ringo was still something of a drinker at the time. I didn’t really notice; he seemed to be in pleasant spirits. Jerry brought in this fiddle player named Doug Kershaw and made us play behind him, and he started playing Jambalaya and wouldn’t stop. I got up on one of the drum risers and started directing and we just started playing the song faster and faster until the fiddle player couldn’t keep up any more. That’s the way we made him stop.

Years and years later when Ringo started doing his All Star shows, he asked me to join him. By that time he was all cleaned up and very well organised. Ironically he was heading up a group of musicians of whom half were in Alcoholics Anonymous and the other half were completely smashed. I managed to straddle a middle ground; I could drink casually and enjoy it and not get into any shenanigans. But at the time, there was Ringo who was in AA, and Zak, his son, who was the other drummer and definitely not in AA. So there was a whole dynamic going on there.

My nemesis was Burton Cummings [The Guess Who]. He was a bad drinker. When he got drunk he would start getting ugly with people, and then the next day he would apologise to everyone and then in 12 hours he was back in the same state again. He was a good example of what not to do. Joe Walsh was also pretty toxic at the time. The thing is that Ringo does not discriminate, he doesn’t tell musicians they have to be on the programme. It just so happens that on every tour I’ve been on there’s always somebody who doesn’t know where to draw the line.

The New York Dolls

In a sense what they did was anti-musical, and at the time I recognised that this was the necessary cyclic thing in music. When rock music gets too flaky or fancy there’s always a movement to break it down. I always thought the reason that certain music critics liked bands like the New York Dolls is because they are doing something that is comprehensible to them.

The New York Dolls weren’t presented to me, they were just part of the milieu I was involved in at the time. I was still living in New York in an apartment that was walking distance from Max’s Kansas City which is where everything was happening; there was no CBGB yet. There were a lot of bands that were performing what was referred to as ‘the New York Scene’; it was not called punk rock yet.

I knew I was going to be leaving New York to move upstate to Woodstock and entering a new phase, so I wanted to do one of these bands as a farewell to my New York lifestyle. The band that was creating the most excitement and actually got signed first was the New York Dolls.

I was such a fixture on the scene and was having wild success with my production work, it was a logical step for me to work with them. I went to see the band play a couple of times and met up with them, and knew that were certain members with whom the musical responsibility lay and then there were guys who were living the dream.

Looking back on it, and having had the recent experience of working with them, that part of it hasn’t changed. It was always Sylvain [Sylvain] and David [Johansen] who were shouldering most of the burden, so I mostly kept a focus on them and tried to manage the other guys, keep them from consuming too much during the course of the sessions.

For the most part I went through David. I used him as a translator to get to the rest of the band. The challenge of making the record [1973’s New York Dolls] was that the control room was a freaking circus; everyone wanted to know what was going on with The New York Dolls – the critics’ favourite band.

I was pretty sober throughout the entire thing, my only working drug was pot. While these guys would smoke pot they would also do everything else. The sessions involved politics, psychology and crowd control. And at a certain point I had to surrender to the process and accept that the surrounding insanity was going to be a part of the character of the record.

Grand Funk Railroad

The Grand Funk Railroad album [We’re An American Band, 1973] was one of the easiest things I ever did. It simply required my normal sensibility, particularly because the band was operating with such low expectations. They’d had some great success but they were not well-regarded critically.

They had a huge live following but were excessively jammy, and if you compared them to real jam bands like Cream they really didn’t hold up. To compound things their manager insisted on producing their records, and he was terrible at it. So by the time I worked with them their expectations for the record were so low I couldn’t fail.

I got involved through photographer Lynn Goldsmith, who was part of the new management team and a good friend of mine. She got the idea of putting us together. And by then the band had spent so much time under the thumb of Terry Knight that they were a little unsophisticated about a lot of things outside their world and they went along with it. By the time I got to them they had already been encouraged to produce stuff that was more in the mainstream.

We’re An American Band surprised a lot of people, and the title track has been covered by countless bands since, most famously Bon Jovi. I haven’t heard their version yet, but that’s because I really don’t pay that much attention to Bon Jovi.

This feature originally featured in Classic Rock 139, in October 2009.