Wire, The Only Ones, Pere Ubu, Gang Of Four – shine a light into the darkest corners of the punk and new wave explosion and you’ll be hard pressed to find a band that doesn’t have its champions.

Britpop darlings Elastica paid homage to (i.e. ripped off) Wire. Gang Of Four have been name-dropped by everyone from Audioslave to a recent crop of punk-funk bands like The Rapture. Pere Ubu have long been a hip name to drop, while The Only Ones have always been cited as one of the great lost bands of the 70s.

Everyone from The Clash to the Buzzcocks to Sham 69 have been lusciously repackaged and reissued, while many others live on in cyberspace, with dedicated web communities for everyone from Stiff Little Fingers to XTC.

But The Skids?

For a band that had several top 20 hits (Into The Valley, Working For The Yankee Dollar, Masquerade), a Top 10 album (The Absolute Game, in 1980), a genuinely gifted guitar hero and a unique (and uniquely Scottish) sound, The Skids have been all but forgotten. There’s no dedicated website. Reissues came out on specialist punk label Captain Oi! to very little attention, and even Scottish rock acts fail to namecheck a band that were one of the most distinctive and ambitious of the time.

Maybe it’s because guitarist and co-songwriter Stuart Adamson went on to form the achingly untrendy (but frequently brilliant) Big Country: not only did this put off the hipsters, but it meant that – unlike the vast majority of punk and new wave bands – a reunion was never on the cards. Neither Adamson nor frontman Richard Jobson having any need or desire to trade on their past.

Adamson took his own life on 16 December, 2001, aged 43. Today, his one time partner Jobson is sitting in a members club in Soho, looking far too young and healthy for someone who fronted a second-wave-of-punk band (though, to be fair, he was only 17 when Into The Valley hit the charts).

Since leaving The Skids, Jobson formed the short-lived Armoury Show, has been a poet, a film critic, a movie director and novelist. Ask him why The Skids have been all forgotten, and he takes some of the blame.

“I’ve never really had any passion to talk about it,” says Jobson. “I wasn’t embarrassed, but I just let it go. I didn’t feel the need to fight for it. I’m not great at clinging on to things.”

One of the people who didn’t forget was U2’s The Edge. Approached with the idea of doing a charity single with to aid victims of Hurricane Katrina, he came up with the idea of a cover version of The Skids’ third single The Saints Are Coming (the New Orleans Saints is the name of the American football team whose stadium was used as shelter while the good people of the Big Easy waited in vain for their government to help them). Released in 2006, it topped the charts around the world.

In 2007, the band reunited for a handful of gigs and played sporadically before reforming for a 40th anniversary tour in 2017. A new album, Burning Cities , was released in 2018, and an acoustic album, Peaceful Times, in 2019. They still tour to this day.

Formed in Dunfermline – home of Nazareth – in 1977, Adamson and Jobson had been unaware of each other until punk. “I went to a Catholic school and he went to a Protestant school,” says Jobson. “He was already in a band, touring all the RAF bases in Scotland, doing cover versions. But they got excited by the punk thing when it happened. I think Stuart always thought of Nils Lofgren as being a kind of punk – which in a way he was, y’know – and they were looking for a singer and the only punk in the area was me.”

Jobson got the gig and was thrown in at the deepest of deep ends. “They said: ‘We’re doing a live gig in two weeks’ time’,” he remembers. “Which we did – at a hotel in Dunfermline where the whole audience ended up on stage fighting me while the rest of the band ran off and left! That was something that dogged us for years, actually – I used to end up fighting the whole audience. This promoter would book us into barn dances in Elgin – and then we’d turn up. So all these big Highland guys would get stuck into us. It was great fun. I was gonna say that maybe the violence wasn’t as serious as it is now, but of course it was – I got stabbed and stuff…”

He won’t elaborate, but Jobson’s first film 16 Years Of Alcohol chronicles the growth of a skinhead who falls in love with an art school student and discovers The Stooges and the Velvets. His gang then turn on – and knife – him. (“It was pretty much as it happens in 16 Years…,” he admits. “My fellow gang members stabbed me.”)

“As a kid I was a skinhead,” he says. “It’s kind of interesting talking about it now because people’s idea of a skinhead is this kind of National Front, right-wing thug. But this was before all that – it was all about music, clothes and football. I’m from an Irish Catholic family, but where I was brought up was in a pretty hardcore Protestant housing estate – I think we were the only Catholics on it…

“The clothes, the music and the violence were part of your daily diet. As a teenager – though it’s shameful to talk about it with any excitement now – it was really exciting. You weren’t persecuting violence against some guy walking down the street, you were fighting other gangs. But most of the time it was about music and hanging out and learning how to dance.”

He grins. “Although quite clearly some people would say that I never did learn how to dance. Maybe that’s where the title of the first album came from.”

Debut album Scared To Dance was a flawed but brilliant mix of keening guitars and anthemic choruses. The critics hated it. “It had a high production value and at the time people found that kind of offensive,” says Jobson. “Stuart was influenced by Bill Nelson and Nils Lofgren – that guitar-led thing – and he did guitar solos.

“I mean,I always thought they were more melodic [rather than just indulgent], like the stuff I used to enjoy: like Steve Hunter, who played with Alice Cooper and Lou Reed. Hunter and Dick Wagner were my two favourite guitar players at the time. Very melodic. Stuart was more from that school.

“I was into ska and R&B,” says Jobson, “then I got introduced to Alice Cooper through my brother: Love It To Death and an album called Killer. There’s an Alice Cooper fan club convention in my new movie, actually… And then there was Leonard Cohen. One day he gave a copy of the New York Dolls album – and that was it for me really – I just saw something there.

“So there was a new thing pulling me away from ska and R&B into a world that was more alienated and lost. I think I was inclined toward that anyway. I was always a little bit ill as a kid – I’m epileptic, but we didn’t know that at the time – and so drifted away from people and spent a lot of time on your own, and that sort of music and my love of cinema merged. Ska was something you really shared with other people whereas Lou Reed is something you can do on your own.”

Signed to Virgin and championed by John Peel, the album yielded a trio of classic singles: Sweet Suburbia, The Saints Are Coming and the Top 10 hit Into The Valley – famously lampooned in an 80s TV ad for Maxell tapes that got all the lyrics wrong. “I really loathed that commercial that took the piss out of the words,” says Jobson. “Stuart gave permission for that in my absence. I would never have said yes to that because the song is about something quite potent for me.

'All of the early lyrics that I wrote – Melancholy Soldiers, Into The Valley, The Saints Are Coming – were all about my mates. Fife was a great recruiting ground for [former regiment] the Black Watch. I would never join cos I’m from an Irish Catholic background and after Bloody Sunday and stuff there was just no way you’d join the British Army – they were seen as some fuckin’ dreadful imperialist force.

"But my mates at the time were facing either Rosyth dockyard or the mines – or unemployment – so the Army recruited pretty hardcore in the estates that we lived in.

“A lot of my mates joined up and within 15-20 weeks they were in Northern Ireland. They joined to become car mechanics and engineers. Into The Valley was about the depersonalisation of these young guys, how they were thrown into the Falls Road and these places. Hell on earth at the time, and they didn’t want to be there. And when they came back, they were changed – you would be, right? – and their attitude toward me changed too, cos obviously I was pro-nationalist and that rankled.

“The Saints Are Coming was about one of my friends who got shot while he was in the army. He’d just had a kid and it was about a kid phoning his father. For me it was also about the death of my own father. Melancholy Soldiers – all those songs, there was a real militaristic sort of thing. So the words were reflections of all that, but rather than do it in straightforward Bruce Springsteen kinda folk-tales, I chose to do it in a slightly different way. But it was a time for experimenting.

For second album, Days In Europa, Jobson was keen to do something completely different – much to Adamson’s horror. As a compromise they got in Stuart’s hero, Be-Bop Deluxe’s Bill Nelson, as producer.

“But by this time Nelson had already moved on from Be-Bop Deluxe into [artier new wave band] Red Noise,” says Jobson, “ and he was much more into the world of Brian Eno. So his influence on me was very strong. He read some of my lyrics and was like: ‘Wow – you should be taking this further.’ So we really engaged – and him and Stuart didn’t, in fact. And I think the seeds of the end were already being sewn then.”

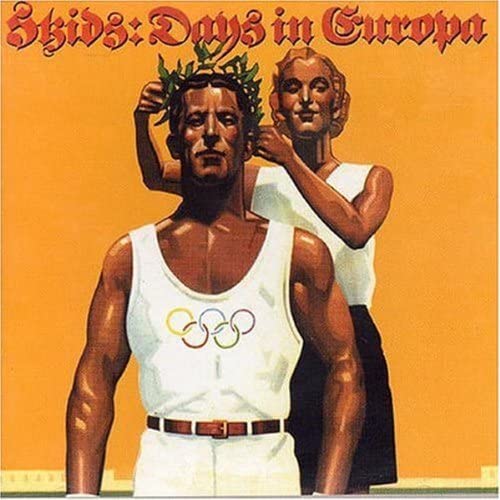

The album sleeve had to be changed after its image of a blond athlete being crowned, complete with Germanic-style lettering, was deemed reminiscent of the 1936 Berlin Olympics and the work of Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl. The idea that the band were flirting with fascist imagery (check the two ‘S’s in their early logo) did them no favours.

“The Aryan thing?” says Jobson. “I thought that sleeve looked great – but I was probably, I dunno, 18 then. But is it in the songs? I don’t think it is. I mean, there’s a song called The Olympian and there’s a sense of Europe… To be fair, I think what had happened is that we’d gone to Europe.

"We’d gone to Amsterdam and it was such a modern place. Britain during the 70s was still kinda like, post-war, even London – you almost felt like you were still on rations. But Amsterdam felt modern. You had all these Bauhaus buildings and everything – and then you’d go to Germany and it had all been rebuilt and was sparkling and exciting. It made a big impression on me that there was this other place out there that was full of excitement and possibility and much more about the future than the past.”

Third album, The Absolute Game, was The Skids’ most perfectly realised collection – a series of anthems filled with mythological imagery and Adamson on top form (“It’s Stuart at his best,” says Jobson, “All those little riffs and licks”). Adamson left during the early stages of last album Joy, and The Absolute Game stands as the logical first step to the sounds and themes he captured on Big Country’s classic debut The Crossing.

“I wanted to evolve quick and I ran around a bit like a headless chicken, grabbing anything that influenced me and using it,” says Jobson of the split. “I didn’t really care about the response to it, it was just the doing of it that was exciting. Whereas I guess probably Stuart was more measured.”

Would he try and hold you back? “No, but I think he thought I was an uncontrollable force at times, and I’m sure I pissed him off all the time. We never really had big arguments; we were just different people. He was more tuned into a world that was kind of real: he wanted a house and a family and those things while I didn’t really expect to be alive after the age of 25. I was always a little bit ill as a kid – I’m epileptic – and I was shadowed always by that.

“I’m fine now, actually – it’s something that I’ve managed to control – but I always had that in the background and, without being too melodramatic, you always had this sense of foreboding that you might not be here for that long so you might as well have a little sample of everything. But here I am.”

Classic Rock reads him a line from an interview he and Adamson did with a fanzine way back in 1978. “It’s not a friendship,” Adamson tells the interviewer of the pair’s relationship. “Richard won’t ever have friends. I think he’ll commit suicide eventually.”

“Wow,” says Jobson, surprised. “That’s quite a strong thing to say. And, of course, y’know…”

…Look what happened.

“Yeah,” he says. “It was a real shock about Stuart. I was so shocked. Because he was never a man of extremes. I was, because to me it was about grasping it before it was taken away from you.

“Because of my background I always expected someone to come along and go: ‘Game’s up now pal, there’s your rifle. Now get marching’.”