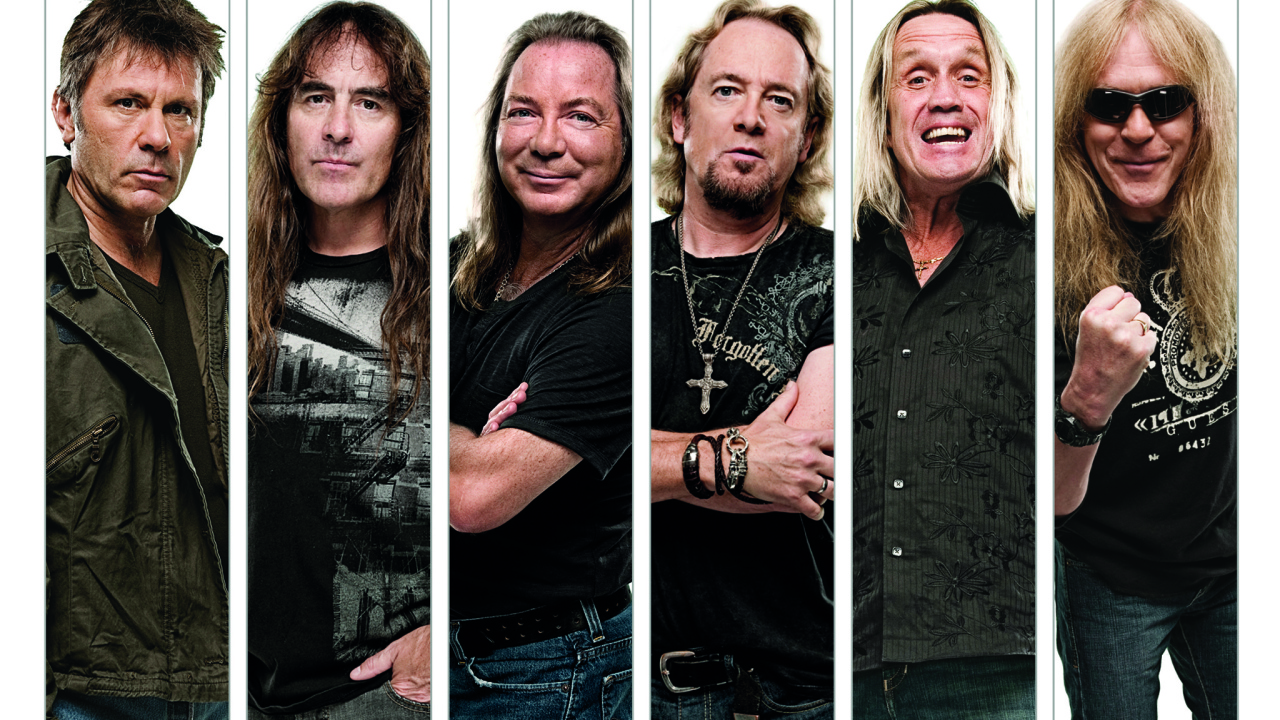

Nobody had seen it coming. At the end of 2014, just a few weeks before Christmas, the six members of Iron Maiden should have been celebrating. In Paris, they had just finished recording a new album, The Book Of Souls. The consensus within the group was that this album would be one of the best they had ever made. It was also going to be a first for Maiden: a double studio album. And for its grand finale, it had the longest and most ambitious track this band has ever recorded, an 18-minute epic named Empire Of The Clouds, written by singer Bruce Dickinson.

It was while mixing the album in Paris that Steve Harris said something strangely prophetic. Harris, the founder, bassist and leader of Iron Maiden, was with guitarist Adrian Smith. It was just the two of them in the studio. Harris turned to Smith and said: “If this was our last album, it would be a good one to go out on.”

It was only a few days later that Harris received a call from the band’s manager Rod Smallwood. He was told that Dickinson had been diagnosed with cancer of the head and neck. Only after the initial sense of shock and disbelief had subsided did Harris remember what he had said in Paris. “I was scared,” he says now. “I mean, Christ, it was really scary for Bruce, obviously, but there were implications for all of us. First, you had to think about how Bruce was feeling. But for the rest of us it was like, well, is this it then?”

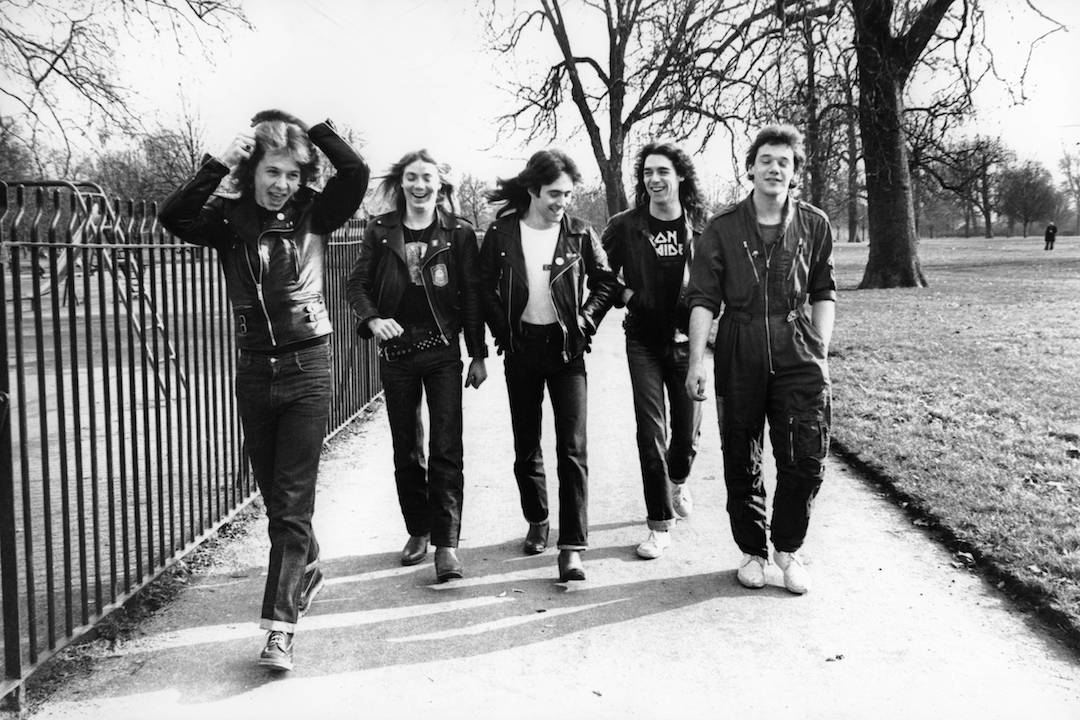

It’s exactly 40 years since Steve Harris formed Iron Maiden in the East End of London, and in all those years, it is he and Dickinson who have been the dominant figures in the group. It’s Harris’s vision that defined the band, and it’s his leadership that has driven them on to huge success, and kept the group together through good times and bad. Equally, it’s with Dickinson that the band have reached their greatest heights: in his first tenure, from 1981 to 1993, and following his return to the band in 1999.

The two men have had their battles: Harris the working-class hero with a quiet authority, Dickinson the outspoken former public schoolboy. The split, when it came in ’93, was acrimonious, and in Dickinson’s absence, the band struggled during the ensuing years when Blaze Bayley was their singer. But when both parties bowed to the inevitable in 1999 – Dickinson rejoining Iron Maiden, along with Adrian Smith – it led to a comeback that was astonishing for the scale of the band’s renewed popularity, and for how long it has continued. This late-career renaissance has rolled on for 15 years, completely untroubled, until Dickinson received his diagnosis.

News of his condition was only made public in May, after he had been given the all-clear following a course of chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment. His full recovery was confirmed on August 25 with the announcement that Iron Maiden will embark on a world tour in 2016, on which the singer, a qualified airline pilot, will be flying the band’s chartered Boeing 747, a role he first undertook in 2008 on the Somewhere Back In Time tour. For Bruce Dickinson and Iron Maiden, it marks the end of a period in which nothing was certain.

It is four weeks before the announcement of Iron Maiden’s 2016 tour that Steve Harris speaks to Classic Rock. It is a warm evening in Bristol, and Harris is at the Bierkeller, one of the city’s many small venues. Here, the entertainment mostly involves tribute acts or oompah bands and the aroma of stale beer permeates the place. “Nice here, innit?” he says.

For the bassist, it’s a place that evokes memories of the band’s early tours in the late 1970s. What brings him here today is a tour with British Lion, his other band, which he operates during his downtime from Maiden.

Over the following eight days, all six members of Iron Maiden will be interviewed separately: Bruce Dickinson in London, the others calling from their homes in the UK, Florida and Hawaii. Harris chooses a quiet place to talk, away from the noise in the Bierkeller. The tour bus in which British Lion are travelling offers a degree of luxury in contrast to the venues in which they’re playing, a luxury Harris can easily afford. For all that he is, a rock star and multi-millionaire, he has no airs and graces about him. He’s dressed down in T-shirt and shorts. His East End accent hasn’t softened, nor the straightforward manner in which he talks.

There’s only one discernible difference between Steve Harris now and in past interviews. For a man who has never been easily given to speaking of his personal life and emotions, Harris is now more open, less guarded. This comes, in part at least, from his experiences in the past year: not just the fear that Bruce might not make it, but also the realisation that the future of his band had to a great extent been taken out of his hands.

Can you describe the moment when you were told that Bruce had cancer?

It was such a shock. It was a shock to him, a shock to everybody.

You feared not only for Bruce but also for the future of the band. Did you think it might be the end?

There was the realisation that it might be. It was very depressing all round.

How soon did you contact Bruce?

I left him alone for a while. I sent him a couple of texts wishing him well, but I waited until he wanted to speak to me. He started the treatment very quickly, so I wasn’t going to call him asking how he is. I thought he probably wouldn’t be able to talk anyway. I just sent him a text saying, “Call me when you’re ready.” And eventually he did.

Was that a difficult conversation?

I was surprised, because his voice sounded the same as ever. He wasn’t groggy. But he told me he’d been through the hoop with the treatment. It was tough for him to talk about it.

And now, after Bruce’s treatment has proven successful, what’s next?

Hopefully I’m not talking out of turn, but the biggest problem now is that his mucus membranes are really dried up. From what I’ve read, I don’t think they come back a hundred per cent. But knowing Bruce, I wouldn’t bet against it.

When did he start singing again?

The last time I spoke to him, he told me he hadn’t been singing, but I know he was telling me porkies. Someone told me he’d been singing, and that it sounded okay. We don’t want him to run before he can walk, and Bruce will be very impatient to get back to where he was, but he’s not daft. That’s why we’re not touring this year. He needs time to recuperate.

Would Iron Maiden have committed to another tour even if Bruce had not fully recovered his voice?

It’s about whether the fans would accept it, and I think they would because Bruce, even at seventy per cent, is still better than most people out there anyway. That’s how I feel about it.

Is that your decision, or his?

It’s totally his decision. I can’t tell him he’s got to get himself in shape and do a bloody tour!

The orders of Führer Harris?

That’s probably what certain people think I’m going to do! [Laughs] But it’s not my decision to make. Maybe you can ask him that question because I haven’t spoken to him for about three or four weeks, and that’s a long time when you’re recuperating.

You and Bruce have had a difficult relationship in the past. In the 80s and early 90s there was an intense rivalry between you and him.

There were a few… debates, let’s put it like that. Since he came back, there’s been nothing that I can think of. He’s a lot more easy-going these days, and so am I. At least I like to think so.

Everybody changes over time.

It’s something you learn. I’m not all peace and love now, but you mellow out as you get older.

Has Bruce’s ordeal brought the two of you closer?

It doesn’t take something like that for us to be close. Our relationship has been great for years. But yeah, I think we’ll be even tighter after this.

When you were in conflict, how did you manage that situation? Did you simply ignore the problem?

The stiff upper lip, yeah. You get the hump for a few hours and you go quiet. That hasn’t happened for a long time. But it’s a weird thing, being in a band. You’re together for long periods of time and then you don’t see each other for ages. Maybe that’s what has kept this band together, because we all live in different parts of the world.

You’ve led Iron Maiden for 40 years now. Do you remember the exact moment when you realised: this is everything I ever dreamed of?

I’ve felt it several times. The first was when we sold out The Marquee in 1978. When we did Running Free on Top Of The Pops, that was a big thing for a metal band at the time. The most recent was when we had our own plane on the Flight 666 tour. I said, “Fuck me, it’s like being in Led Zeppelin!” But I never lose sight of reality.

As the leader of the band, what’s the hardest decision you’ve ever had to make?

When someone has to be told they’re not in the band any more. That’s the toughest thing. Especially when you like people – that makes it even harder.

In all these years, have you ever seriously considered breaking up the band?

I did after Bruce left the first time. I sulked for two hours, then picked myself off the floor and thought, “No, fuck this. This is a challenge – I’m going to keep this together.” But it was tough, because at the time I was going through a divorce, so I was already at a low ebb. I thought: “The rest of the guys will look to me for strength now, and I’m not sure I have it.” But I found something from somewhere.

Was that the lowest you’ve ever felt in your life?

Everybody has tough times. You just have to get through these things. I’m not the only one to go through a divorce. Bruce did, Nicko did. And obviously there’s what Bruce has just been through. But that’s what makes you stronger.

You mean as a band as well as individually?

Yeah. We’ve known when to give people space, or when to help them out if they want it. Some people want to talk about things and some people don’t. You just have to learn how that is. It’s something you learn together.

All of your adult life has been consumed by Iron Maiden. Can you imagine your life without it?

Not really. I’ve always liked to think that maybe I’d be able to take it on the chin, but when that happened with Bruce, I started to think, “Oh my God, this really could be it.” It wasn’t a nice feeling.

You’ve always said that you want the band to go out at the top. Is that something you’ve given a lot of thought to, even before recent events?

We know we’re not getting any younger, but before the scare with Bruce, we were thinking we could carry on for a bit longer yet. Then you get that shock and it gives everyone a shake-up. I’ve said it before: every gig is sacred. And from now on, it’s going to be even more like that. You never know what’s around the corner. But that’s life.

You must have played this out in your mind: walking off stage at the end of Iron Maiden’s final show…

Hey, you’re scaring me! [Laughs] Fuck off!

Do you know what you would do with your life after Maiden?

I wouldn’t give up playing. I’ve got British Lion to fall back on. I’ll play to a couple of hundred people a night. I could produce other bands, or write with other people. But the fact of there being no Maiden any more, I don’t like the sound of that.

**If it did transpire that The Book Of Souls was Iron Maiden’s last album, could you live with that? **This is a bit strange. It’s not like we were approaching this album thinking there was a problem with Bruce. But when we were finishing up, I actually said to Adrian: “If this was the last one, it would be a good one to go out on.”

And so?

I’d still like to do another one. [Laughs] And so would Bruce.

In the long history of Iron Maiden, only two men have appeared on every one of the band’s albums: Steve Harris, of course, and Dave Murray. The guitarist didn’t make the best of starts with the band. Shortly after joining Maiden in 1976, he was fired following an argument with original singer Dennis Wilcock. But Murray was reinstated a few months later, and he has remained as Steve Harris’s trusted lieutenant ever since. The reasons for this are simple. As much as he’s a fine guitar player, Murray has another quality rare among rock stars: a gentle, even-tempered demeanour, completely devoid of ego.

He calls Classic Rock from his home on the island of Maui in Hawaii. He’s softly spoken, with an easy laugh that punctuates many of his sentences, this lightness of tone changing only when his thoughts turn to Bruce Dickinson.

Living in a tropical paradise, playing in one of the biggest bands in the world – you’ve done okay for a working-class kid from the East End.

I’ve been very fortunate. Blessed. This band has brought so many positive things to my life.

It’s a landmark year for Iron Maiden: the band’s 40th anniversary.

It doesn’t feel like forty years. Time flies when you’re having fun. And that’s what keeps you in the game. When you’re on stage, the adrenalin you get from the audience reaction, it’s such a great feeling. Nothing can beat that. And also, the creativity is still there. Doing a new album every few years, it makes the band relevant, and keeps your energy flowing.

When you look back over those years, what were the defining moments for the band?

There are so many. Headlining for the first time at Hammersmith Odeon, that was a beautiful moment. Playing Earls Court – I remember seeing Zeppelin there in ’75. Over the forty years there have been lots of good moments.

Considering you were sacked from Maiden in 1976, you’ve certainly managed to stick around for a long time…

Hey, things like that happen. I had words with the singer after a gig and it all got blown out of proportion. I went over to Steve’s house and I was out. But it was done in the nicest possible way. And after a few months I was back in.

You’ve been at Steve’s side ever since. What has made this relationship work for so long?

Good question. I suppose it’s because I’m a team player. For myself, it’s about being part of something that’s way bigger than I am, way bigger than any of us.

You’re also a very easy-going bloke. Is that something Steve appreciates?

I’ve never had an argument with Steve, ever – or with anybody in the band. I don’t like confrontation. I steer clear of it. I’m just not that way inclined.

Iron Maiden is Steve’s band and you respect that. Is that the bottom line?

Yeah. Everything is channelled through Steve. He’s the focus. The rest of us, collectively, add to what makes the band. But Steve has given the band its identity with his ideas, and his approach to writing, which is totally unique and original.

What do you think has kept this band together for so many years?

Sometimes personalities can get in the way, but you have to go beyond that. There are going to be clashes in any band. But we’re intelligent enough to find a way to work harmoniously together.

That hasn’t always been the case – certainly not with Steve and Bruce.

Well, you hear all that stuff about them fighting, but it can’t be like that all the time or we wouldn’t be here now. And after all we’ve been through, this is, I think, the strongest line up of Iron Maiden – and definitely the last line up. This is it!

And the future, for all of you, has been determined by Bruce’s recovery.

We’re just profoundly happy that he’s made a full recovery. When I got the call, I was absolutely devastated. You spend some time crying. We knew that his prognosis was excellent, but there were a few moments when, you know, it’s not certain. Bruce is okay now. He’s bounced back. I’m really happy. But it makes you think. You’ve got to enjoy your life. You can’t take anything for granted.

The longest friendship in Iron Maiden is that of Dave Murray and Adrian Smith, a bond forged when they were at school together in East London in the mid-70s. It was Murray who recommended Smith as the replacement for Dennis Stratton in Iron Maiden in 1980. He left the band in 1990, burned out from a decade of heavy touring. He returned to Maiden, alongside Dickinson, in 1999.

Smith is the least talkative band member, and the most difficult to read. At times he can be extremely candid, when discussing his life and his position in Iron Maiden, past and present. There is, however, one subject he will not go into: his exit from the band in 1990. The reasons for his departure might in part be explained by a few of the anecdotes he tells from the 80s, stories about hanging out with famous hedonists such as Robert Palmer. “Partying,” he says. “That’s the only way I can put it.”

It must feel strange now to know that you were making the album while Bruce was seriously ill.

When I got the call about Bruce, it was just awful. You think: “He’s too young for this.” The band was secondary. I just wanted the guy to get better.

Did you believe he would pull through?

I think, with cancer, the mental attitude is very important. In the last few years we’ve lost two people from our crew – Steve Gadd and Andy Matthews – both of them to cancer. But with Bruce, somehow I never doubted that he’d come through. I couldn’t imagine him letting this thing beat him.

You and Bruce both left the band at separate times in the early 90s and returned together in 1999. In the years when you were out of the band, did you keep in touch with the other guys?

A little. Everyone started having kids so we saw each other mostly at the kids’ parties and because there was a kind of Maiden wives’ club! [Laughs] My family would visit Dave’s in Hawaii. When I left, there were no hard feelings.

It must have been a difficult decision for you to leave Maiden. Did you have any sleepless nights about it?

Yes, of course. It was probably the best decision for me and for the band. But I wasn’t in a good state of mind back then.

Can you elaborate on that?

Honestly, I’d rather not go there. What I’ll say is that the decision was mutual. I think they’d had enough of me as well.

What changed, for you and them, when you rejoined the band?

I’d grown a bit. It might sound strange, but having had kids, having done my solo albums, I just felt a bit more confident about myself.

It sounds strange that you would lack confidence, having written some important songs for the band.

Well, I never considered myself a virtuoso and still don’t. When I was first in Maiden, I struggled with that. I always felt like someone was going to find me out. I’m not a guitar hero – I’m just Aidy Smith from Hackney! [Laughs] But after I came back, the first song we recorded was one of mine, Wicker Man. I felt so happy. And I felt different, having had a break.

Did you think then that you’d still be in Iron Maiden fifteen years later?

Probably not. In fact, when we first talked about me coming back, I thought maybe I’d just do a tour and that would be it. Steve said, “No, I want to have three guitarists. It’ll work.” And once Steve has an idea, he doesn’t change his mind.

So what is the key to the band’s longevity?

We’re all a bit older, a bit wiser. You know what the band’s about and you know what’s best for the band, so that’s what you do. We know each other so well that it just works. It didn’t always work for me. I spent nine years out of the band. But now I appreciate it more. Of course there are egos. Everyone’s got an ego. But we’ve come through all the ups and downs, and here we are – still a pretty strong unit.

Nicko McBrain is the oldest member of Iron Maiden. Now 63, the drummer joined the band in 1982. “More than half my life I’ve been with Iron Maiden,” he laughs. “It’s part of my sinew.”

That booming laugh is emblematic of a larger-than-life persona common among rock drummers. On this level, he is, along with Bruce Dickinson, the biggest personality in Iron Maiden. There is, though, a complexity to McBrain. In 1999, he converted to Christianity following an experience he described as “a calling”. He refers to his faith as a private matter, and sees no conflict between this and his life as a rock star. He says that he gave up smoking dope – “wonga”, as he calls it – in 1986. But only now is he seriously considering giving up alcohol as the rigours of touring harden with age.

He calls from his home in Florida, near Fort Lauderdale, where he has lived for more than 20 years with his second wife, Rebecca. Unchanged by all those years in America is his blunt working-class London accent.

We all know what the two hardest jobs in a rock band are – Bruce’s and yours. How are you bearing up these days?

I’ve got to be honest, the older I get, the harder it becomes to do this. That’s one of the reasons I haven’t had a drink for three months.

And?

I feel fucking old! [Laughs] At least when I was drinking I didn’t feel it, except for the hangovers.

Seriously?

I feel good, actually. But I needed to start looking after my body a bit more. I’ve started to get a bit of arthritis in my hands. There’s a gruelling tour coming up next year and I’ve got to be fit. I’ve taken a lot of inspiration from the way that Bruce has fought his way back to health. He’s a strong man, Bruce.

Even so…

Well, I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t feared the worst when they mentioned the C word. It was a very heavy time. For his family it must have been unbearable. But my feeling in my heart was, he’s such a strong guy, not just physically but mentally.

As a practising Christian, did you pray for Bruce?

I prayed every day for him. I believe in the good Lord, and my prayers were answered, as well as the prayers of everybody else.

Do you think the other guys in the band might have said a few prayers for him too?

I’m sure they did. Bruce also told me he was singing Heaven Can Wait in the shower, which is classic Bruce humour.

When Bruce was going through this, did you re evaluate your own life?

We’re mortals, and you do question your mortality when something like this happens. But he’s over the hurdle now. I understand Bruce is doing a bit of flying again now, so he’s got to be all right.

Who in the band are you closest to?

At a pinch, I’d say Steve. He’s my confidante. If I have things I need to talk about, it’s Steve I turn to.

I hate to betray his confidence, but Steve says you’re the biggest moaner in the band…

Ha ha ha. You bastard! But I suppose Steve is right. I’m the one that moans and groans and flies off the handle. At the same time, I’ve always been the comedian of the band, the life and soul. But when I have an off day, yeah, I’m the moany one.

Steve and Bruce have had their differences in the past. What changed?

It’s like when two people fall in love, get married, then separate, and end up getting married again. There’s a love affair going on, and the sex is the music. It’s not a gay thing, don’t get me wrong. It’s a weird analogy! [Laughs] But that’s what I feel.

When you’re not working with Maiden, what do you do with your life?

I go out and twat a golf ball. And I have another band, The McBrainiacs. Funnily enough, it’s an Iron Maiden tribute band. We do a bit of AC/DC, Purple, Hendrix, but primarily it’s Maiden songs.

Do you think much about life after Maiden?

I’ve thought about it, I’ll admit that. But I can’t see us hanging it up any time soon. Let’s get one thing straight: we would never become a parody of ourselves. But it’s my job to drive Maiden, and one day I’m not going to be able to do it any more.

So, realistically, how long have you got?

Ideally… ten years? Nah, don’t see that. Imagine me trying to play Run To The Hills at fucking seventy-three years old! So I don’t know, mate. But I’m planning on bowing out gracefully.

Janick Gers is the one member of Iron Maiden who was not present during the band’s rise in the 1980s. Even so, the guitarist has been a fixture for the last 25 years, having joined in 1990 as the replacement for Adrian Smith. Born in Hartlepool, Gers has now settled close by, in Yarm, a small town near Stockton-on-Tees. He’s alone in his house when he calls. His wife and two teenage children are on holiday without him, on the Greek island of Kos. “I’m enjoying a little peace and quiet,” he says. “I’ve always been comfortable in my own company.”

Gers was a member of White Spirit, NWOBHM-era contemporaries of Maiden, before joining ex-Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan’s solo band, Gillan. With Iron Maiden he has enjoyed a level of success far beyond anything he had previously experienced, yet he remains a man of simple pleasures. “I like the nice things in life,” he says. “But it doesn’t take a lot to make me happy.”

Steve lives in the Bahamas, Dave in Hawaii, and you live in a little place in the North East of England…

Where the north winds blow cold! [Laughs] But I like it here. It’s half an hour from where I was born. The people are great. I go out for a drink most nights and wander home by myself. I’m in my own little bubble here.

Is living in Yarm the perfect antidote to life in a famous rock band?

Yeah. I forget I’m in a band until someone asks for a photo at half-one in the morning when I’m in the pub and my nose is bright red. I’m comfortable in my own company, and I like being in a place where nobody knows me.

When the band aren’t working, do you socialise with the others?

When I’m in London I see Bruce, but he has another clique of friends that talk about aeroplanes, which I can’t handle for more than a few minutes. We all live in different places, so we don’t get much chance to meet. But they know where to find me – in the pub round the corner.

Are there certain qualities that are required to be a member of Iron Maiden, beyond musicianship? A degree of humility perhaps? A sense of your place in the group?

That’s it exactly. You have to be down to earth. We all have our idiosyncrasies, but we seem to fit together. There has to be give and take between us. The Who, there was a negative atmosphere in that band. Jagger and Richards had that negative/positive energy. It’s part of the mechanics of a band. But we get on tremendously well.

It wasn’t always so.

No. When Bruce left, everybody was hurt. We all felt we’d been left high and dry. It was a really difficult time. But we carried on with Blaze, and we did okay.

Did you have reservations about Bruce and Adrian coming back to the band?

You’ve got to build bridges. I’m a big fan of [Japanese director Akira] Kurosawa’s movies: he’ll show you five different perspectives of the same thing. And you’ve got to understand that when you’re in a band. After Bruce and Adrian came back, we couldn’t have been happier.

You’re close to Bruce. How did you deal with the news that he had cancer?

I’d been in hospital that week with my brother-in-law, who had also been diagnosed with cancer. So the call about Bruce, it knocks you on your back.

Did it bring a sense of your own mortality?

Of course. Not long ago I lost both my parents when I was away on tour. Those things make you feel very deeply.

Since Bruce got the all-clear, have you celebrated with him?

We had a night out recently, drinking, and he was in fine form. He told my wife how much weight he’d lost, and she said, “That’s not really the way to do it, Bruce!” That put me at ease. And he was buzzing. It was the old Bruce.

And so, going forward, what’s next?

The band can’t go on forever. We knew that before Bruce was ill. We’ve talked about it. But the band is still vital, still growing. The new album proves it. I don’t know how long we can keep that up. I still love it, we all do. But if the moment ever came when we’d lost that energy, that desire to keep pushing forward, I’d like to think we’d all be man enough to say we’ll stop.

It’s a sunny morning when Bruce Dickinson meets Classic Rock at a private members’ club on Chiswick High Road. He’s lived in this part of West London since 1981, with his family.

Clad in plain black T-shirt, baggy gym shorts and trainers, Dickinson has arrived this morning on a bicycle. He cycles most days, each time a little further. He’s noticeably thinner, having lost weight during his courses of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. His face is a little pale and drawn. Apart from that, his appearance is unchanged, and in conversation, he is his usual ebullient self.

Typically of a man with an expensive private education, Dickinson has always been a high achiever, not only as the singer for a famous rock band, but in his other interests. In the sport of fencing, he competed for Great Britain. As an author, he wrote two satirical novels. He worked as a pilot on commercial flights for the now-defunct airline Astraeus, and he’s in the process of setting up his own airline. The Boeing 757 he piloted during Maiden’s Somewhere Back In Time tour has been upgraded to a bigger and more powerful 747 for next year’s tour.

At 57, Dickinson is the youngest member of Iron Maiden. It’s one reason, he says, why he never expected that he would be the one who would end up staring death in the face…

How did you discover you had cancer?

We were in Paris, in the middle of making the album, and… something wasn’t right. I knew it and I could feel it. I had earache. I thought, “It’s November, maybe it’s a cold.” But I also had this lump on my neck. So I went on Dr. Wikipedia and diagnosed myself. It seemed, in all probability, that I had the human papillomavirus, a tumour on my tongue. In layman’s terms, it’s cervical cancer of the gob. If a woman gets cervical cancer, it’s squamous cell carcinoma. This is squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue.

So then what?

I ignored it. I thought: “Internet hypochondriac. Don’t be daft.” I didn’t go the doctor.

Why not?

Because I thought, “If I am right, I don’t want to know. Not now. I want to know when I’ve finished the album. Then I’ll deal with it.”

Most people in that situation would rush to a doctor to make sure that if it was cancer, they would be treated immediately.

I know. But I wanted to finish the album.

Did you tell anyone? Your wife?

No. I sort of mentioned it in passing, the lump on my neck. She said, “Oh it might be glandular fever.”

How convinced were you that your self-diagnosis was right?

Fifty-fifty. Deep down, I knew there was something wrong.

How soon did you seek out qualified medical advice?

Six weeks later. We were finishing the album and I saw a doctor. He had a feel around my neck. Then he went straight for the goolies. I thought, “He’s either very friendly or very thorough.” He said, “You need a head and neck scan and a biopsy of that lump.” A few days later I saw my doctor in London.

And your self-diagnosis proved to be correct?

Absolutely. I’d wondered how they tell you. Is it over tea and biscuits? But the oncologist just said, “Well, I have a letter here that says you have head and neck cancer.” So that’s how they do it: straight between the eyes. I appreciate that. I was told I had a golf ball-sized tumour on my tongue, and another in my lymph node. But the oncologist also said: “You’re an excellent candidate for a complete cure.” He told me, “I’ll get rid of this for you and it won’t come back.”

Did you believe that, or did you fear the worst?

I thought I would probably be okay, on the balance of probabilities. I’d gone quite heavily into the medical research papers on the internet. I had nothing better to do. I’d looked at my odds. With my age and my profile, it was eighty per cent in my favour.

It’s the other twenty per cent that would put the fear of God into most people.

I didn’t see the point in being fearful. You know me – I’m quite bouncy anyway.

Even so…

Well, I went through a couple of days of ‘poor me’ and ‘why me?’ But a mate of mine had a better question: not ‘why me?’ but ‘why not me?’ This wasn’t the universe having its revenge on me. It’s just random shit. It’s got to happen to somebody and it’s happened to me. So, crack on with it. If the outcome is bad, it won’t be for want of trying.

What was your state of mind like in the days that followed ?

All I noticed for three days after my diagnosis was graveyards and hospitals. And when I sat at home watching daytime TV, there were all these ads – ‘Cancer. We can beat it together’ – and ads for life insurance. But after those three days, I thought, “Stop it. Start noticing women’s legs and pubs again. Get back to normality.”

Was there anything else you could do?

I started taking mushroom supplements. I asked the oncologist if that was okay. He said, “That’s fine – as long as you’re not taking any heavy metals.” And I went, “Really?” He meant iron or whatever.

That sounds like a line from a bad sitcom.

It is! But there’s a black humour in all of this. I got all of the one-liners out of the way early. Like when people ask, “Why aren’t you touring?” I say, “The reasons are too tumourous to mention.”

What treatment did you have?

I had nine weeks of chemotherapy. In that same period I had thirty-three sessions of radiation. The effect of the chemo was… interesting. A lot of strange sensations: like an out-of-body experience. And the last two or three weeks was… yeah, rough. I’d get zapped, go home and just sit on the couch. My full-time job was just to try to get liquid and food down. Liquids only, oral morphine, and oral antibiotics, because your immune system is on the floor. Milkshakes I could just about manage. My tongue hurt so much, I couldn’t speak – a blessing for the wife. My way of getting to sleep at night was to put kitchen roll soaked in Bonjela around my back teeth so it would anaesthetise my tongue. Then it would wear off and I’d wake up in the middle of the night going, “Aaargh!”

So was this a psychological battle as much as a physical one?

It was. Because you had to drink so much fluid every day, I’d sit there with my head in the sink going, “Okay, one more gulp of water.” After the first diagnosis, they’d offered me a feeding tube. I said, “Fuck right off. I’ll feed myself. I’ll get it down somehow. If I can’t, you can shove a tube up my nose, like they do with hunger strikers. But I will do it.” And the doc said, “Fair dues.”

What would you say was your lowest point during this whole process?

The last three weeks were the worst. To be honest with you, you’re so flat-out knackered that you don’t have the energy to be enthusiastic about anything.

Did they put you on the heavy stuff, morphine?

Ah, the old morphine! [Laughs] I was taking it by the spoonful, and it was a bit disappointing, really. I wanted to see pink elephants! I was expecting to want to cut my ear off. But – nothing. It was all rather underwhelming.

When this was happening, who knew about it?

Nobody except my immediate family, and Rod and the band. After I got the diagnosis, Rod said we should tell the press, and tell the promoters why we’re cancelling the tour. I said, “Don’t fucking tell anybody! Can you just wait until at least I’ve finished going to hospital every day? Fucking hell!” So we timed the announcement with the end of my treatment.

Steve says that when he got the news, he sent you texts because he didn’t think you’d be able to talk, or want to.

He was right. But I’ll tell you what else he sent me – three books on how to beat cancer, and a trampoline! [Laughs] It was fucking brilliant. A mini-trampoline, so when I was watching daytime telly I’d have something to do.

After the radiation, had you lost your hair?

No. But I grew a big, shaggy beard, like Captain Haddock [from the children’s comic Tin Tin], and that fell out – all at once, from under my chin, in the pub.

What were you doing in a pub?

Having a beer!

Ask a silly question…

I couldn’t taste the beer. I lost all sense of taste as soon as I started chemo. But I had to get out into the world at some point, so why not the pub?

You’ve now had the all-clear. Is that definitive?

Yeah.

Could the cancer return?

In theory, yes, so I have a check-up every month for the first year.

After all you’ve been through, how has this changed you?

From a practical point of view, I take lots of mushroom supplements [laughs].

And on a more profound level?

You mean the spiritual side of things? No great revelation on that score. There was a brief moment of, oh, mortality might be cropping up a bit sooner than I expected. But I thought: “I’ll deal with that when they finally tell me you’ve only got a year or two left.” In which case, I’ll say, “Well, I’ll beat that.”

In all of this, has your relationship with the other guys in the band changed?

Yes, depending upon how people are. Some people are just, “Wow, I’m really glad you’re okay.” Other people are: “I’m glad you’re okay because it scared the life out of me that you might go and I might be next.” Some people project their own fear upon you. When they give you a hug, what they’re actually hugging is this sense of: “I’m so relieved I’m still alive.” You can detect that.

Steve had said to Adrian, before they knew you had cancer, that if the new Maiden album were the last, it would be a good one to go out on…

I felt the same thing going into the treatment. Before I could see there could be a positive outcome, I thought, “If this was the last thing I ever recorded, with this voice, as it were, it’s a pretty good way to bow out. It would be ironic.”

In what way ironic?

That you do this great double album, with this amazing song Empire Of The Clouds, and people are saying, “Oh my God, you’re singing better than ever.” And then, suddenly, it’s gone.

Steve thinks that Empire Of The Clouds is a masterpiece. Is it the most important song you’ve ever written?

For me it was – and doubly so after I got diagnosed. The story in that song is very poignant. The R101 was this amazing airship, the equivalent to Concorde and the QE2 rolled into one, and it crashed on its maiden voyage. There were only five survivors. As a kid I built a big plastic model of the R101, and the story stuck with me.

There are many epic Iron Maiden songs, but none quite so epic as this.

Exactly! I wrote it on piano, and I’m a two-fingered pianist. I thought at one point, “Ooh, this is a bit Billy Joel.” And then I decided on a little overture at the beginning, a nice bit of cello, some horns. None of the instruments that I had in my head was a guitar. It was written for Irish fiddles – diddle-de-diddle-de-diddle…

In fairness, diddle-de-diddle-de-diddle is very Iron Maiden.

Totally Iron Maiden! It was designed for fiddles, but I knew in reality it was going to be guitars. And that would Maiden-ise it immediately.

And now the album is finally released, what next?

I’ve got the most difficult period at the moment. I’m running around doing all kinds of other stuff, but with the voice, I just have to wait. I don’t like waiting. Last December, I asked the doc: “Assuming I get rid of this, how long before I’m back to normal?” He said about a year. I said, “I’ll beat that.”

Typical Bruce Dickinson.

Absolutely. It’s a challenge.

When did you start singing again?

I had a little go in the kitchen, a little yell. It was interesting. The upper-mid register was a bit yodelly, a bit Von Trapp family. I sang a few notes, got it warmed up, so I thought I’d let rip. I tried one from the new album, If Eternity Should Fail. Then I had a go with The Trooper. And I thought, “It’s there.”

So that voice, the Air Raid Siren – will it sound the way it did before?

It needs time, like Doctor Who, to regenerate. It’s had a pretty good kicking from the radiation. The very top of the voice, that’s great. The low end is fine too. It’s only the only mid-range of my voice that needs some work. I might have to go to vocal rehab. I might have to take some lessons.

And what does all this mean for the future – for you and for Iron Maiden?

Well, the worst case scenario was: I have the treatment, I don’t get rid of it, and then the guy says, “Sorry mate, you’re on your way out.” The best case scenario was: you get rid of it, everything gets back to normal, and there will be no difference at all in your voice. Well, that last bit hasn’t happened yet. But I’m absolutely confident it will. Wild horses are not going to stop me from getting back on that stage. And you know, I’m still here. I won.