For Iron Maiden, 1989 was supposed to be a well-earned year off. Their last album, the acclaimed Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, had been their most ambitious yet, and the attendant Arctic-themed stage show had given the Powerslave-era set a run for its money. Most bands would have taken the chance put their feet up, congratulate themselves on what they’d achieved and reconvene 12 months later, rested and re-energised.

But putting their feet up wasn’t Iron Maiden’s style. For Steve Harris, a chunk of the year was taken up editing Maiden England, a live concert video recorded on the Seventh Son tour that he had also directed .

Bandmates Adrian Smith and Bruce Dickinson were no less restless. The former had launched ASAP, a hard rock side-project that found him stepping up to the microphone. The latter had released a solo song, the gloriously OTT Bring Your Daughter… To The Slaughter, on the soundtrack to slasher movie A Nightmare On Elm Street 5: The Dream Child, and was in the process of recording a full album away from the comfort of the mothership. “The intention,” he later explained to the band’s official biographer Mick Wall, “was to do something you wouldn’t do in Maiden. “Otherwise what’s the point?”

When Iron Maiden gathered in November 1989 for the lavish launch party for the Maiden England video, everybody seemed to be in good spirits. There were plans for the band to reconvene in the not-too-distant future to start work on their new album, a record that would be a back-to-basics reaction to Seventh Son’s vaulting scale.

As the five members of Maiden watched assorted journalists and music industry types empty the free bar and stuff themselves on good old fashioned British fish and chips, the future looked rosy. Little did they know they were about to enter the most turbulent chapter of the band’s history – one that would see the departure of both Smith and Dickinson.

- The best wireless headphones you can buy right now

- The best metal guitars 2020: Get ready to shred with our essential list

- Best record players: turntables your vinyl collection deserves

- Shop for the best Bose deals

The plan for Maiden’s eighth album was simple: work fast, don’t mess around. Harris had been impressed by the directness of Bring Your Daughter… To The Slaughter, and figured that Maiden would benefit from the same approach. In fact he liked the song so much that he asked Dickinson not to include it on his solo album so that Maiden could re-record it themselves, to which the singer agreed.

“I was happy that Steve liked something so much,” said Dickinson. “In fact, I wandered back into Maiden to start the new album a very happy-go-lucky little leprechaun.”

Dickinson released Tattooed Millionaire in May 1990. It may not have featured Bring Your Daughter…, but it had plenty of other highlights, including epic opener Son Of A Gun and the anthemic pop-metal of the title track. That inimitable voice aside, it bore little resemblance to his day job – its grab-bag stylistic approach took in everything from the reflective Born In ’58 to the raucous single-entendre rock’n’roll of Dive! Dive! Dive! (“No muff to tough!”). The quality might have been variable, but it did the job it was designed to do and took Dickinson out of his Maiden-shaped comfort zone.

Adrian Smith hadn’t fared quite so well. The guitarist was a classic hard rock songwriter at heart, and ASAP’s debut album, Silver And Gold, reflected this. But Smith’s voice and personality weren’t quite quite as big as Dickinson’s, and Maiden’s fans weren’t quite ready for something that strayed so far from the established blueprint. Silver And Gold had caused a ripple of interest on its release in 1989 before disappearing largely without trace.

- The 50 best Iron Maiden songs of all time

- Iron Maiden's Somewhere In Time: the story behind the album

Its lack of success coincided with Smith’s growing disenchantment with life in Iron Maiden. He was also concerned that ASAP had “sent the wrong signals… they were worried that I wasn’t into doing metal any more.”

Like any good leader, Steve Harris sensed his bandmate’s predicament. The pair were good personal friends, but Harris’ professional priorities lay with Maiden. The bassist called a meeting and asked if Smith wanted to stay in the band. When he answered that he didn’t know, Harris made the decision for him – albeit against his better wishes. “It gutted me that he didn’t want to be there any more, but I thought, ‘We’ve got to be strong about this,’” he recalled.

In typically unsentimental fashion, Maiden wasted no time in replacing him. Janick Gers was an amiable six-stringer from Hartlepool who had played with ex-Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan, NWOBHM-era outfit White Spirit and former Marillion singer Fish. More importantly, he had recently played on Tattooed Millionaire. Gers was invited to an audition, though he was such a shoe-in that he told the job was his after just three songs.

This urgency extended to the new album. Opting to record in the UK for the first time since 1982’s The Number Of The Beast, the band reconvened with longtime producer Martin Birch. Rather than a traditional studio, they elected to work in a barn on the grounds of Harris’ Essex estate. The recording process took just three weeks.

“It is mainly more aggressive than the previous albums,” said Harris at the time. “I think that some of our fans were disappointed in the musical orientation we had taken lately. So I think they'll be happy to see that we're going back to a more aggressive and powerful style. The band still has the fire anyway.”

With hindsight, that fire didn’t translate to the album. No Prayer For The Dying was made with noble intentions, but it never quite exploded. Opener Tailgunner was a classic Maiden Boys’ Own anthem in the vein of Aces High and Where Eagles Dare, even if it didn’t scale the lofty heights of its predecessors. Lead-off single Holy Smoke was a scabrous takedown of US televangelists, their version of Bring Your Daughter… To The Slaughter rattled with metallic toughness and the soaring title track stands as an unsung mid-period classic. But other songs, such as The Assassin and the ponderous Mother Russia, lacked the energy and power that defined Maiden.

Released on 1 October, 1990, No Prayer For The Dying reached No.2 in the UK and No.17 in the US – both lower than its predecessor, Seventh Son Of A Seventh. While second single Bring Your Daughter… would give Maiden their first ever No.1, it was clear that something was off.

“We tried to get the album to sound as live as possible,” Harris later recalled. “For me it didn’t quite come off. But again it depends on who you’re talking to. Some people think it’s our best album and some people think it’s our worst. Me, I don’t think it’s our best but it’s certainly not our worst.”

For all its flaws, No Prayer For The Dying did succeed on one level: it successfully repositioned Maiden for the incoming decade. The back-to-basics sound pre-dated the rise of grunge, itself a reaction to the excess of the 1980s. Ironically, the man spearheading that movement, Kurt Cobain, had once scribbled Iron Maiden logos in his schoolbooks when he was younger.

But the grunge explosion was a few months off, and Iron Maiden had plenty to think about anyway. Chief among these was correcting the course they had embarked on with No Prayer. This may partly explain why Harris chose to step up as co-producer alongside Martin Birch for their next album.

Returning to Harris’ barn – now converted into a proper studio, aptly named Barnyard – they recorded their ninth album, Fear Of The Dark, at a slower pace than its predecessor. The results were more polished, even if the likes of opening one-two Be Quick Or Be Dead and From Here To Eternity still crackled with the energy that Harris had strived to recapture last time around. But they brought back a couple of longer songs too, notably the seven-minute title track which would rapidly become a live favourite.

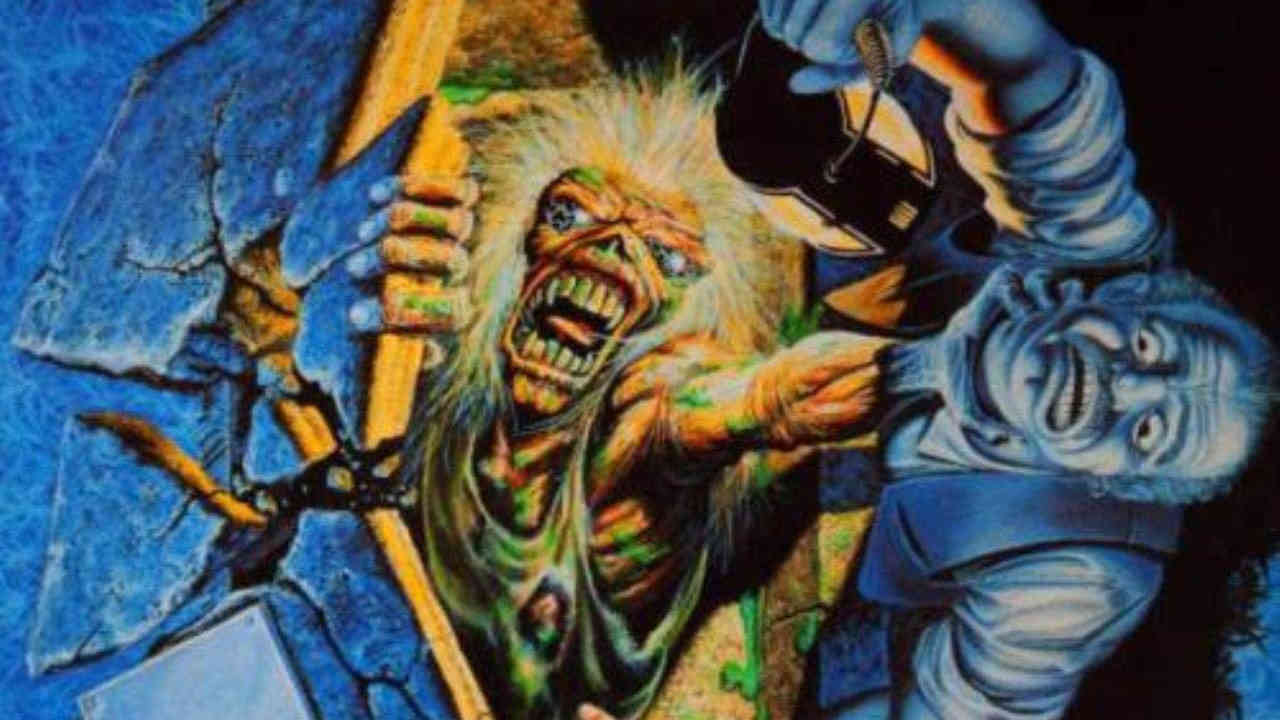

However the biggest change came with the cover. Rod Smallwood sensed that Maiden’s visuals needed updating for the new decade, and decided that some new blood was required. “We wanted to upgrade Eddie for the 90s,” Smallwood explained. “We wanted to take him from the sort of comic-book horror creature and turn him into something a bit more straightforward so that he became even more threatening.”

Fear Of The Dark would be the first Iron Maiden album not to feature artwork by Derek Riggs, the man who had created Maiden’s mascot all those years ago. Instead, the image of a vampiric Eddie crouching on a tree was illustrated by fantasy artist Melvyn Grant.

Maiden’s fans weren’t unsettled by this change if chart positions were anything to go by. Fear Of The Dark restored Maiden to No.1 in the UK and reached No.12 in the US – the same as Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son (it remains the band’s best-selling album in America).

- We got Chris Jericho to pick his fantasy Iron Maiden setlist

- Iron Maiden’s Powerslave: the story behind the most epic metal album of the 80s

Maiden kicked off the Fear Of The Dark tour on June 3, 1992 with a secret show under the name The Nodding Donkeys at the tiny Oval Rock House in Norwich. On 22 August, they returned to the Monsters Of Rock festival at Castle Donington in Leicestershire. Where their previous appearance had been marred by the tragic deaths of two fans earlier in the day, this time they served up a vintage Maiden performance for the ages, even inviting Adrian Smith onstage to play Running Free.

Behind the scenes, though, trouble was brewing. After the tour finished, Bruce Dickinson travelled to Los Angeles to begin working on a second solo album. Rod Smallwood visited the singer in the studio. That’s when Dickinson dropped a bombshell: he wanted to leave Iron Maiden.

“It was all about stepping out of what was a pretty comfortable regime,” he later explained. “Hard work, good guys, relatively safe, well-managed. All the things people would say, ‘He, that’s a comfortable job.’ That was my life in Iron Maiden. I thought, ‘It’s not enough. I’m too young to be settling down.’”

Dickinson’s announcement threw Harris for a loop. For the first time in his professional career, the bassist was unsure of the future of Iron Maiden. He called Dave Murray and told his old friend that he didn’t know whether the band would continue.

“I did have a doubt as to whether to carry on or not,” recalled Harris. “I thought, ‘I just don’t have the strength at the moment.’”

Murray himself had no such qualms. “We were all sitting around talking,” said the guitarist. “It was probably the first real long, serious talk the four of us had had together in ages. I suddenly just got fed up talking about it and went, ‘Look, why the fuck should we give up just cos he is? Bollocks to him. Why should he stop us playing?’ I hadn’t really thought about it. It just came out.” Murray’s impromptu pep-talk worked. Harris had the impetus he needed to continue the band.

Maiden had another tour lined up through the spring and early summer of 1993. Ever the professional, Steve Harris refused to cancel it and the band took the bold step of announcing Dickinson’s departure at a press conference just before the tour began, assuming it would work as a chance for the fans to say goodbye to the singer. It quickly became apparent that the reality was very different. The atmosphere at the shows was awkward at best.

“It wasn’t a good vibe," Dickinson later admitted. “We walked out onstage, and it was like a morgue. The Maiden fans knew I’d quit, they knew these were the last gigs and I suddenly realised that, as the frontman, you're in an almost impossible situation.”

Worse, backstage tensions between Dickinson and his soon-to-be-ex-bandmates had hit rock bottom. This was partly down to Harris’s view that the singer wasn’t giving it his all.

“We all though thought he was really out of order and that he wasn’t performing,” said the bassist. “The worst thing was, if he’d been fucking crap, over the whole tour, you can sort of understand it, but this was specific times. It was so calculated. I really wanted to kill him.” The singer refuted the claims, but the bad blood would linger after he had left the band

Bruce Dickinson played the last show of his original run with Iron Maiden on August 28, 1993 at Pinewood Studios just outside of London. The show was filmed as an MTV special and it featured magician Simon Drake, who concluded the show, appropriately enough, by ‘killing’ Dickinson. It pretty much reflected how the rest of Maiden felt.

Dickinson’s departure marked the end of an era for the band – one that had seen these East End heroes scale heights they could only have dreamed of. Replacing him wouldn’t be easy. But Steve Harris and Iron Maiden had never ducked a challenge before, and they weren’t about to start now.

Published in Classic Rock And Metal Hammer Presents: Iron Maiden