In 1984, Iron Maiden were poised to take over the world. They’d been on a skyward trajectory since the arrival of vocalist Bruce Dickinson three years previously, and had laid the groundwork on the increasingly ambitious tours accompanying The Number Of The Beast and Piece Of Mind.

But the band’s fifth album, Powerslave, would literally set the stage for their most epic undertaking yet. Beginning in August 1984 and ending 331 days and 189 shows later in July 1985, the Egyptian-themed World Slavery Tour helped turn Maiden into one of the biggest metal bands of the decade and produced one of the all-time great live albums in 1985’s Live After Death.

The tour kicked Maiden to the next level in America but it also pushed the band members themselves to their mental and physical limits, almost bringing the group to an end. We look back on that crazy time, in words of the band and those around them.

Bruce Dickinson (vocals): “We rehearsed for the tour in a wonderfully tacky nightclub in Fort Lauderdale, and stayed in a cockroach-infested seafront motel. Soon enough, the holiday was over. It was time to emigrate to the Evil Empire, behind the Iron Curtain, as it was in 1984, to Poland to open the Powerslave tour.”

Steve Harris (bass): “I didn’t really think about the political side too much. I wonder whether we’re being used as a propaganda tool, but at least we’re providing entertainment for the kids.”

Bruce: “The reception was outrageous. It wasn’t just people who liked the band going crazy like at normal shows. I felt straight away that they weren’t just coming out for something to do on a Saturday night – there was real change in the air everywhere. It was a moment of hope, and I felt like we were this beacon.”

Howard Johnson (journalist present on the Polish dates): “What’s really weird is that there were young soldiers in full army uniform talking their shirts off for a mosh and throwing their hats in the air for added pleasure in amongst the assorted human carnage.”

Nicko McBrain (drums): “We ended up going to, well, it was supposed to be a disco, and it ended up being sort of like a converted ballroom. So there was this wedding going on at the time, about 300 people dancing the waltz as we walked in. Then these people in the club said, ‘Would you like to have a jam?’ ‘Yes,’ we said, and we did.”

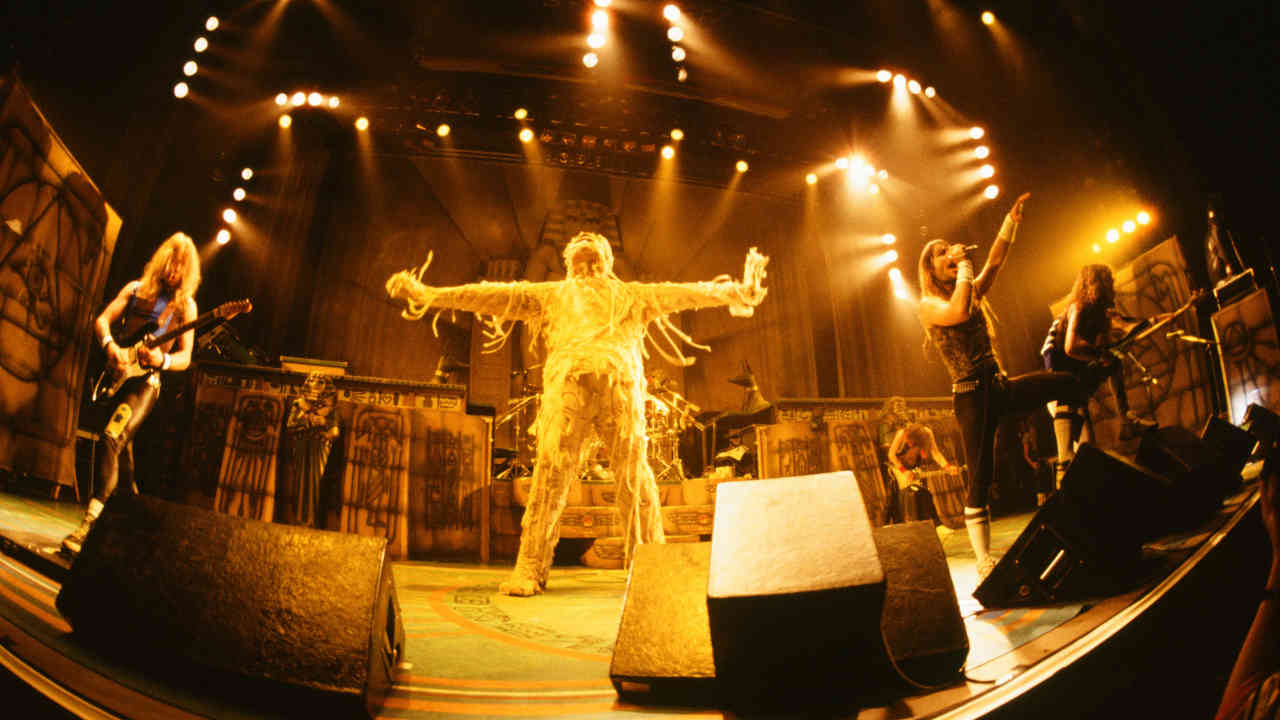

The World Slavery Tour’s impressive, Egyptian-themed staging was already in place, but as the juggernaut moved from Europe to North America, the venues went up in size and an even bigger stage set was deployed, featuring sarcophagi, a huge Sphinx-like Eddie head looming over the stage, and a mummified version of their mascot. However, as the band’s ambition grew, so did the distances and pressures involved.

Charlie Kail (stage set engineer): “[The set] took two months to build. We did things like building lighting into the hieroglyphics – those details really made it special… The whole thing probably cost £145,000 – a lot back then. But Maiden were the pioneers of those big shows in heavy metal.”

Bruce: “I still think that was the best show that Maiden ever put on. It was just the right combination of epic stuff, but it wasn’t too overblown and it wasn’t so hidebound by the sort of technology and loads of hydraulics and inflatable things that occurred later, all of which had the possibility for Spinal Tap-type fuck-ups on a regular basis.”

Charlie: “There were some groundbreaking special effects, like the Eddie-on-a-stick. At one show, they parked the cherry picker too near the stage, and when the big reveal happened, all you could see was Eddie’s head bobbing up and down behind Nicko McBrain. I could feel [Maiden manager] Rod Smallwood’s eyes boring into the side of my head.”

Bruce: “Virtually everybody I know who’s seen one of our shows expects to see some sort of phenomenon that’s going to corrupt the morals of their town. What they see is 7-10,000 young kids having a great time, enjoying themselves, with a show that delivers a lot of value for money.”

Adrian Smith (guitar): “When we first started out in America, we went from one bus to two buses to seven buses… so things do become more comfortable. More comfortable than when we first toured the US with Judas Priest in ’81! We don’t have to sleep on our luggage anymore.”

Nicko: “Some people do sort of crack underneath the pressure of being on the road constantly and living out of a suitcase. I sometimes don’t even know what the day is – I maybe know the date.”

Adrian: “It got on top of me a few times and when we hit America things really kicked in with booze and drugs, using it as a crutch.”

Iron Maiden roared into 1985 with an appearance at the inaugural Rock In Rio in Brazil. They played on January 11, the opening night of the now-legendary festival, where they were second on the bill below Queen.

Adrian: “It’s very difficult to do anything in Rio because the fans are very passionate, and even back in the first Rock In Rio they were outside the hotel, and we couldn’t go out. Even when we sat out in the balcony having breakfast, there’d be people in the buildings taking photos and looking at you through binoculars.”

Bruce: “We conquered an entire continent overnight with that one show.”

Adrian: “It wasn’t as well organised as it is now – back then it was a bit chaotic.”

Bruce: “Hot and bothered, I wrenched the guitar off, over my head, and split my forehead open on its wooden edge… [A roadie] looked carefully at the wound. ‘Rod says can you squeeze it and make it bleed some more,’ he said. ‘It looks great on the telly.’ Next day, the picture was front-page news: sweaty, bloodstained me… and 300,000 new Iron Maiden fans.”

Adrian: “We were touring in New York state in the winter and it was 10 foot of snow everywhere. Then we went down to Rio and it was hot and we were partying – we came back and all got sick immediately. But Rock In Rio, that was a very exciting time.”

Maiden had been on the road for almost six months by the time they played Rock In Rio, but there were still another six months left of the tour. A four-night stint at Long Beach Arena in Orange County, California in March 1985 would – along with earlier shows at London’s Hammersmith Odeon – provide the basis for the Live After Death album.

Steve: “We wanted to record all of [Live After Death] from Hammersmith but we ended up recording three sides from LA because by that time we were just playing that bit better.”

Malcolm Dome (journalist who saw the Long Beach shows): “I’d seen the band at Hammersmith Odeon the previous October, and that was impressive. But as the lights dimmed, the crowd erupted, and you knew [Long Beach Arena] was going to be a different level of hysteria… This was Maiden elevated to the stature of the biggest bands in America.”

Adrian: “The worst part is [when] you’ve been on the road for six months and you realise you’ve got another six months to do. It’s like doing time. You’re kind of in your own cell anyway, a little cocoon – either in a plane or a hotel or a bus, and there’s security guards. It cuts you off from real life.”

Bruce: “At no point on the tour did we ever get to the point where anybody hated each other. We held that end of it together very well. Because we all realised what each of us was going through, and if someone threw a wobbler – which we all did at some point – it was, ‘Shall we leave the room and let him wreck the place and come back later?’ Because everyone was going through it.”

Steve: “That tour fried everybody, and [Bruce] in particular. Christ, he had to get up and sing six nights a week for 13 months, and that took its toll. Our schedule then was insane. It wasn’t like anyone twisted our arms, we were totally up for it, but perhaps we took on more than we could deal with.”

Bruce: “It was the first time I really thought about leaving. I don’t just mean Maiden, I mean quitting music altogether. I really felt like I was pretty much basket case material by the end of that tour, and I did not want to feel that way. I just thought, ‘Nothing is worth feeling like this for.’ I began to feel like I was a piece of machinery, part of the lighting rig.”

Rod Smallwood (manager): “We should’ve stopped sooner. It was probably one of many mistakes I’ve made. But, you know, it was really hopping for us then and I was impatient. The jungle drums were summoning more and more people, and we wanted more.”

Iron Maiden did survive the tour and became one of the biggest metal bands in the world on the back of it. It was not without cost, however. As well as the personal toll it took on individual members, it opened the first few cracks that would eventually see Bruce quit the band.

Steve: “We were never obsessed with breaking America. We always planned to come out here and give everything we’d got, and they’d either like it or they wouldn’t. Fortunately for us they liked it. In fact they bloody loved it.”

Bruce: “It felt like the world had just shrunk. We’d sort of conquered everywhere. Not just played, but really had an impact. But it was hard work. The World Slavery Tour was great, but on a personal level I thought, ‘This is all well and good, but I can’t be doing with another 13-month tour.’ It did my head in. I ended up taking a back seat creatively on the next album [Somewhere In Time] because I was basically fried.”

Steve: “The stuff Bruce was coming up with [for Somewhere In Time] wasn’t us at all. He was away with the fairies, really.”

Bruce: “I came very close to quitting music after the Powerslave tour. I was in no mood for any more backstage politics or solitary confinement in tour buses or gilded cages. I didn’t expect others to understand, because I’m sure for many it might seem like the ultimate dream, but I wanted more than the challenge of standing still successfully.”

Nicko: “I’m really surprised we got through that tour… When you get to that stage, it’s just not fun any more; it’s becoming too tedious or too difficult, emotionally. I mean, it nearly destroyed the band.”

Additional sources: What Does This Button Do? By Bruce Dickinson, Run to the Hills by Mick Wall, Iron Maiden – Behind the Iron Curtain, Metal-Rules, Kerrang!, Forbes