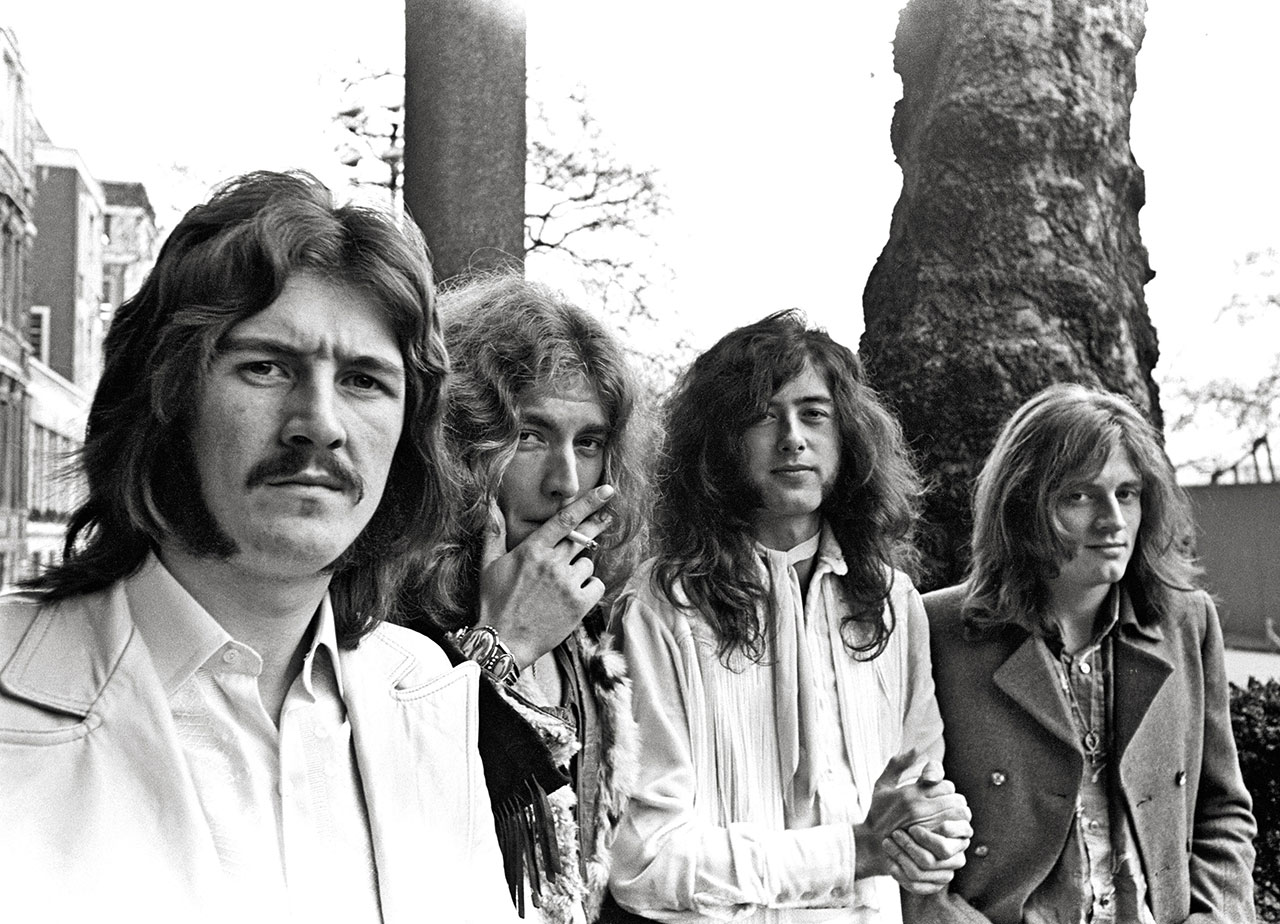

By the time Led Zeppelin returned from their latest US tour in April 1970 – 25 ‘heartland’ dates, no New York, no LA, just deep inside the belly of the beast – what Robert Plant called “the craziness count” had definitely gone up. John Bonham, whose bouts of homesickness seemed to be growing in direct proportion to how successful the band became, began drinking more heavily and taking out his frustrations on hotel rooms. The show at the hockey arena in Pittsburgh at the end of March had to be stopped when a bloody brawl erupted in the audience. Elsewhere, cops hassled the band members at their own shows, blaming them for the uncontrolled antics of the audience.

“I don’t think we can take America again for a while,” John Paul Jones said at the end of the tour. “America definitely unhinges you. The knack is to hinge yourself up again when you get back.”

Plant suffered, too. “More than anyone, Robert seemed on the brink of collapse,” tour manager Richard Cole later noted.

As usual at the tour’s end, they took refuge in West Hollywood, though no longer staying at the Chateau Marmont – the Manson murders the year before had thrown all of LA into a fug of paranoia, and manager Peter Grant decreed the Marmont’s spread of isolated bungalows too easy a target for any potential “nutters”, of which there were more than a few now following the band around on tour. Instead, they had relocated to the Hyatt House (or the “riot house”, as Bonzo and Plant now dubbed it) a few blocks up on Sunset. There, a never-ending parade of girls found their way up to the ninth floor where the band and their entourage were sequestered for a week. Richard Cole remembers the limo for the shows being so weighed down by girls that “the trunk [had] become stuck on the riot house driveway, requiring a push off the kerb… absolute madness.”

Yet just as Zeppelin were reaching the height of their on-the-road notoriety, they were also on the cusp of making their most enduring music. The monumentally successful Led Zeppelin II album was only the beginning. In fact, they only really began to make the giant leaps forward musically that would cement their reputation as one of the all-time rock greats with what came next, starting with what was arguably their first proper album together: Led Zeppelin III.

Written and conceived, in large part, in reaction to both criticism of their first two albums and their own frustrations at being forced to write and record so quickly and under so much pressure, the beginnings of the songs – and indeed the album that followed – were undertaken in much less stressful circumstances. The end result would take everyone by surprise. The whole tenor of the album – acoustic-based songs, rooted in folk and country, as well as their already well-established blues influences – were the last thing anyone, including Jones and Bonham, who were largely excluded from the songwriting process, would have predicted at that point.

Until then the question had been: how would they top the ecstatic thrill of that titanic second album? Would they be able to come up with another Whole Lotta Love?

The answer was: they didn’t even try to. “People that thought like that missed the point,” Jimmy Page told me years later. “The whole point was not to try and follow-up something like Whole Lotta Love. We recognised that it had been a milestone for us, but we had absolutely no intention of trying to repeat it. The idea was to try and do something different; to sum up where the band was now, not where it had been a year ago.”

And where the band was now – or where Page and Plant were, anyway – was halfway up a mountainside in sunny Wales.

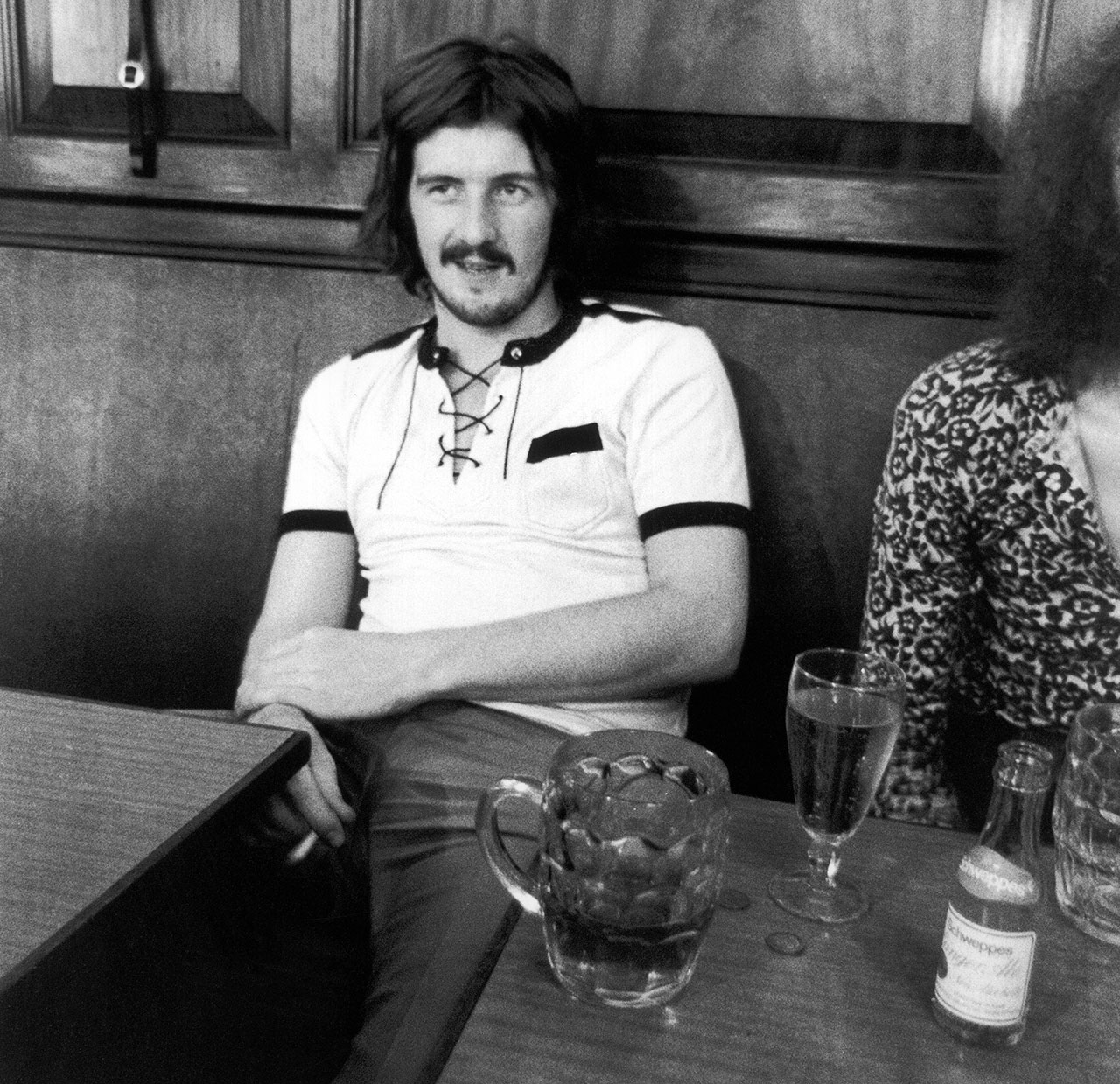

With the final show of the US tour cancelled when an exhausted Plant’s voice gave out, they flew home from Las Vegas on April 20. Between their first show in December ’68 and their latest in April 1970, Zeppelin had performed in the US no less than 153 times. They were now playing for guarantees of up to $100,000 per show (more than $625,000 in today’s money). It was also now, in the spring of 1970, that they received their first substantial royalty payments. The year the band began to live large. Twenty-four-year-old John Paul Jones bought himself a big new place in Chorleywood, Hertfordshire, which he and his wife Mo and their two daughters moved into as soon as the band returned from America. Twenty-two-year-old John Bonham finally moved out of the council flat in Dudley he’d been living in since he’d joined the band two years before, and relocated the family to a 15-acre farm in West Hagley, on the borders of Worcestershire and the West Midlands. Plant, not 22 until August, had already paid £8,000 (more than £92,000 today) the year before for a similar dwelling, Jennings Farm, near Kidderminster. He now set about spending several more thousand refurbishing it. Page kept the boathouse in Pangbourne that he’d owned since his Yardbirds days, and bought Boleskine House – home of occultist Aleister Crowley 50 years before– on the banks of Loch Ness.

But while Bonham and Jones immersed themselves in nest building, Plant was restless, and began talking to Page on the phone about a remote 18th-century cottage in Wales that he recalled from a childhood holiday. He told Jimmy how his father would pack the family into his 1953 Vauxhall Wyvern and take them for a drive up the A5 through Shrewsbury and Llangollen into Snowdonia; places with strange names, full of tales of swords and sorcery.

The cottage, named Bron-Yr-Aur (Welsh for, variously, ‘golden hill’, ‘breast of gold’ or even ‘hill of gold’, pronounced Bron-raaar) had been owned by a friend of his father’s, and stood at the end of a narrow road just outside the small market town of Machynlleth in Gwynedd. Plant further intrigued Page by telling him of the giant Idris Gawr, who had a seat on the nearby mountain of Cader Idris, and how legend had it that anyone who sat on it would either die, go mad or become a poet; how King Arthur was said to have fought his final battle in the Ochr-yr-Bwlch pass just east of Dolgellau.

Page, who had only just begun to restore the interior of his own new mythological abode, Boleskine, to its former glories, was equally taken by the idea of some time away from it all. Before committing full time to The Yardbirds, he had been an occasional solo traveller, moving through India, America, Spain and elsewhere. Now, with his new French model girlfriend Charlotte Martin by his side, and Plant talking of bringing his wife Maureen and infant daughter Carmen (and his dog Strider, named after Aragorn’s alter ego in Lord Of The Rings), plans were laid for a sojourn into the Welsh mountains.

Both men had also been very taken by the debut album the year before by Bob Dylan’s former backing group The Band, Music From Big Pink, famously named after the country house it was recorded in, in Upstate New York.

Page and Plant weren’t the only musicians newly influenced by The Band’s ramshackle musical blend of rock, country, folk and blues. Eric Clapton had been so bowled over he had actually flown to Woodstock and asked to join the band, an overture they merely laughed at as they sat there rolling another joint. George Harrison had also since flown out to hang with The Band in LA, where they’d fetched up to record their second album.

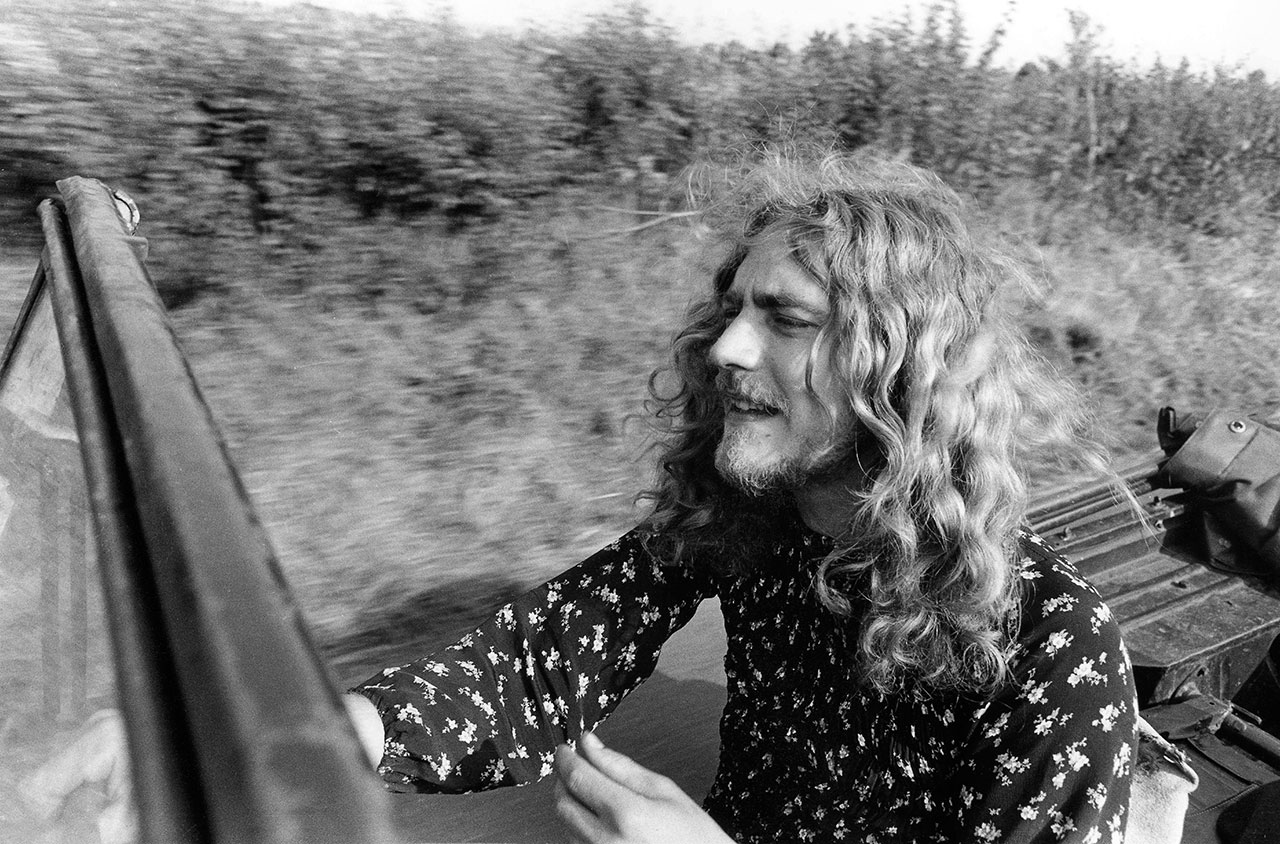

Suddenly everyone, including all of Led Zeppelin, had beards, along with a new pastoral chic in sharp contrast to the blend of mod sharpness and pre-Raphaelite foppery that had dominated their look early on. There were other influences too, such as Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, whose deeply spiritual, if somewhat bleak mix of folk and soul Plant was particularly taken with. And Joni Mitchell, whom Page now became besotted with, partly through her inspiring use of different acoustic guitar tunings, which were almost a match for his own in their range and obscurity, and partly through her remarkably honest and clearly autobiographical songs – and of course her long blonde hair and aquiline features.

The huge impact of Crosby, Stills & Nash, whom Plant had seen at the Albert Hall in London just before Zeppelin played there in January, had also been noted with intense interest by both men.

Above all, there was simply the desire to prove something that neither the critics nor even the fans had picked up on yet, which was the fact that Led Zeppelin were not a one-trick pony. That there was more to Jimmy Page, certainly, than a growing collection of great rock riffs, not least his deep and abiding interest in the acoustic guitar.

As soon as Plant suggested the cottage, Page saw the potential. As he would later explain: “It was the tranquillity of the place that set the tone of the album. After all the heavy, intense vibe of touring, which is reflected in the raw energy of the second album, it was just a totally different feeling.”

When in May Page and Plant arrived at Bron-Yr-Aur, situated along a steep track that leads through a ravine, they found a stone dwelling so derelict it had no electricity, running water or sanitation. Fortunately, as well as their respective partners, they had also brought Zeppelin roadies Clive Coulson and Sandy Macgregor with them, both of whom were now saddled with domestic chores.

“It was freezing when we arrived,” Coulson remembered. He and Macgregor would be sent to carry water from a nearby stream and gather wood for the open-hearth fire, “which heated a range with an oven on either side”. There were Calor Gas heaters but only candles to light the place. “A bath was once a week in Machynlleth at the Owain Glyndwr pub. I’m not sure who got the job of cleaning out the chemical toilet.”

Evenings off would also be spent at the pub, where they mingled with local farmers, the local biker gang and some volunteers restoring another old house nearby. When invited to join in on Kumbayah one night, Page apologised and explained he didn’t play guitar.

Meanwhile, back at the cottage, where Page did play the guitar and Plant warbled on his harmonica, the songs began to come, sometimes just scraps, sometimes fully formed. Songs that would “prove there was more to us than being a heavy metal band”, as Page put it. Chief among them, Friends, built on some esoteric scales Page had brought back with him from a trip to India in his Yardbirds days, laid over a conga drum; Plant’s dreamy That’s The Way; the rousting (misspelled on the record) Bron-Y-Aur Stomp.

There were also several begun there that would find a home not just on the next Zeppelin album but also on their next four albums, including the bare bones of Stairway To Heaven, Over The Hills And Far Away, Down By The Seaside, The Rover, Poor Tom and (similarly misspelled) Bron-Y-Aur.

Of the tracks that did make the third album, there was also Tangerine, with its nicely low-key, deliberate-mistake intro, a song originally begun at a disastrous final June ’68 Yardbirds session in New York as a song called My Baby, now reborn in Wales as a country-tinged, Neil Young-inspired dirge.

Bron-Y-Aur Stomp had also begun life as another, electric number, Jennings Farm Blues, laid down at Olympic Studios in London the previous autumn. Here it was transformed into a jugband hoedown dedicated to Plant’s dog Strider. ‘Walk down the country lanes, I’ll be singin’ a song,’ Plant warbled cheerily. ‘Hear the wind whisper in the trees that Mother Nature’s proud of you and me.’

The song that really summed up the spirit of adventure at Bron-Yr-Aur was one that arrived almost unbidden late one afternoon as Page and Plant traipsed through the surrounding flower-decked hills, then in full spring bloom. Stopping to smoke a joint and admire the view, Page took the guitar he’d been carrying on his back and began strumming some random chords, half-remembered from Bert Jansch and John Renbourn’s arrangement of the traditional The Waggoners Lad.

To his delight, Plant began singing along in a much more restrained voice than usual, ad-libbing the opening to what was originally called The Boy Next Door but later became That’s The Way. Afraid to lose the moment, they pulled a cassette recorder out of a knapsack and recorded the rest of it then and there. Afterwards they celebrated by sharing some squares of Kendal Mint Cake, then made their way back to the cottage where they sat in front of the fire, eating a fry-up and drinking cups of cider mulled by red-hot pokers, listening to endless repeats of the tape.

“We wrote those songs and walked and talked and thought and went off to the Abbey where they hid the Grail,” Plant later told writer Barney Hoskyns. “No matter how cute and comical it might be now to look back at that, it gave us so much energy, because we were really close to something. We believed. It was absolutely wonderful, and my heart was so light and happy. At that time, at that age, 1970 was like the biggest blue sky I ever saw.”

Jones and Bonham were equally taken with the rough tapes of the songs Page and Plant had returned from Wales with. But back at Olympic at the start of June, the band struggled to recreate the atmosphere in the stale environs of a professional recording facility. So they decided to decamp once again, this time for a dilapidated mansion in Hampshire named Headley Grange, where, with the aid of the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio, they hoped to have the album finished before returning to the road in America in August.

Headley Grange had been found by Grant’s secretary, Carole Browne, through an ad in The Lady. Once again, Page was attracted to the setting more by its history than by its practical application. Headley Workhouse, as it was originally known, was a three-storey stone manor built in 1795 in order to “shelter the infirm, aged paupers, orphans or illegitimate children of Headley” and nearby Bramshott and Kingsley. In 1875 it was bought by a builder who converted it into a residence and renamed it Headley Grange.

With the advent of mobile studios and the 60s fashion for “getting it together in the country”, the Grange began to be let out to rock groups by its widowed owner. Both Genesis and Fleetwood Mac had recorded there previously.

With both Page and Plant still enchanted by their newly consummated creative union, they were especially susceptible to their surroundings, and the austere, often bleak mansion appealed to the same sense of adventure as their trip to Wales.

“It really looked to me as if it had been… not derelict, but it looked as if it had hardly been lived in,” Page revealed. “It was quite interesting considering the tests we were going to put it to.”

As Plant put it, “We were living in this falling down mansion in the country. The mood was incredible.”

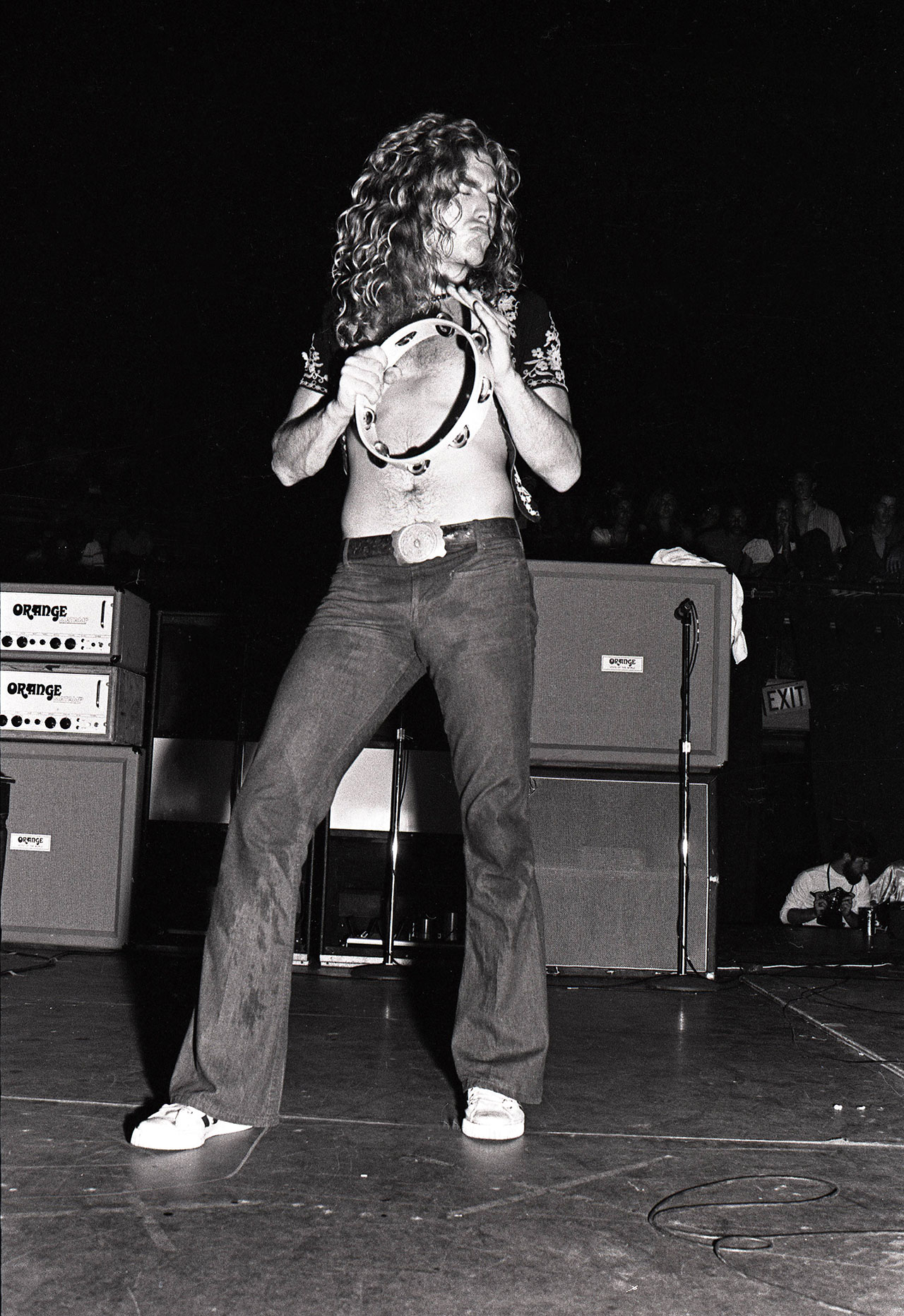

It wasn’t all work, though, with the band breaking for two weekends to play some gigs. The first two shows were in Iceland, on June 20 and 21, at a converted gymnasium in Reykjavik, from where they returned to Headley with a new, distinctly non‑acoustic battle cry of a number called Immigrant Song, Plant solemnly intoning, ‘We are your o-ver-looords…’ to chilling effect. The staff at the venue were on strike at the time, so the local student body ganged together to help put on a show. “The students took over,” Plant says now, “and got the whole thing going and it was just amazing. When we played there it really did feel like we were inhabiting a parallel universe, quite apart from everything else, including the rock world of the times.”

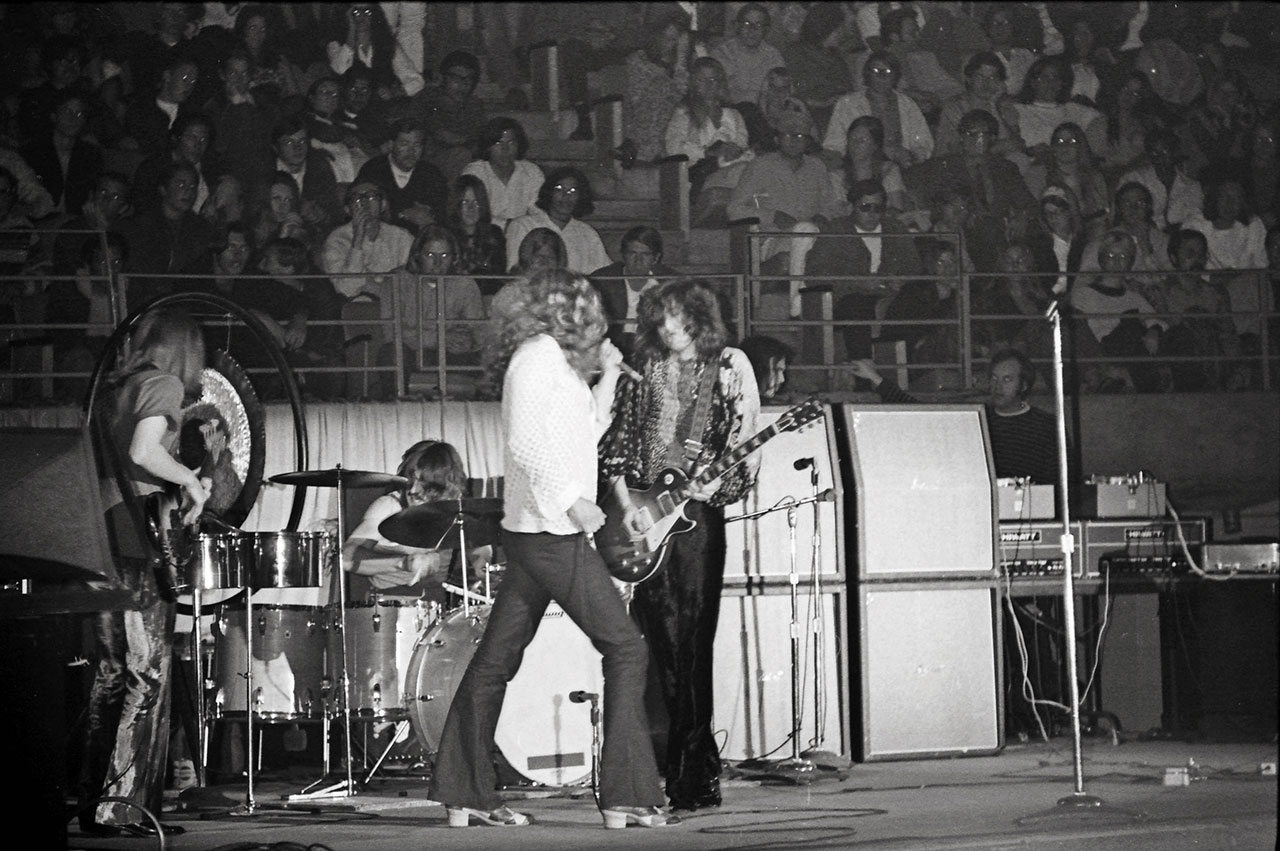

The following Sunday evening they were back for their second Bath Festival appearance, this time held in Shepton Mallet at a much larger site than the first, where more than 150,000 people eventually showed up over the duration of the two-day festival. The official line peddled by Zeppelin manager Peter Grant to the press was that the band were playing at Bath despite an offer of $200,000 to play in America that weekend – almost certainly Grant’s shrewd attempt to drum up a bit of useful PR for the event. Nevertheless, it became another key moment in the winning over of the British music press.

BP Fallon, then working as PR for T. Rex but soon to become Zeppelin’s publicist, was at Bath and remembers it well: “I was there as a punter, me and my girlfriend, on acid in the VIP enclosure at the very front. The sunset was tickling the skies, and this Led Zeppelin monster exploding into action yards away was like a fucking rocket going off and carrying us to Mars and beyond. Whoosh! Sonic sex! Beyond brilliant, you know?

“But there was no strategic follow-up, not really. People in Britain knew that Led Zeppelin were doing very well in the America, but mostly they were lumped in with Ten Years After or Savoy Brown or Keef Hartley or whoever, this blues-based Second British Invasion Of America.”

It was after Bath, though, that Zeppelin began their rapid ascent in Britain to what Fallon describes now as “full-on and on fire. After that, Led Zeppelin were treble-mega in Britain. Tick that box! Next!”

Zeppelin’s near-three-hour set began with a halo of sunlight descending into the horizon behind their heads, the band dressed, as per their new pastoral mode, as tweedy troubadours, heavily bearded, Page even sporting what looked like a scarecrow’s hat.

“I remember Jefferson Airplane and Janis Joplin were also on the bill,” said Plant, “and I remember standing there thinking: ‘I’ve gone from West Bromwich to this! I’ve really got to eat this up.’ The whole thing seemed extraordinary to me. I was as astonished as the audiences some nights.”

- Led Zeppelin reunion rumours circulate

- 25 things you didn’t know about Led Zeppelin III

- How Led Zeppelin III Was Their Most Misunderstood Album

- The top 10 best Led Zeppelin songs, as chosen by Trans Am

It was also at the Bath Festival that Page first met Roy Harper, destined to become the titular subject of another of the songs on Led Zeppelin III, Hats Off To (Roy) Harper. Rustic jester and folk troubadour Harper exerted an unusual influence on everyone he came into contact with, including Led Zeppelin.

Harper was a stereotypical English eccentric whose formative years had seen him feign madness to get out of the RAF, the result of which was five years in and out of mental hospital and prison. He spent the early part of the 60s reading poetry and busking around Europe. Having washed up in London in 1964, he became a fixture on the folk circuit, where Page had first noticed him, before eventually recording his own albums, all quite distinct, all utterly uncommercial.

Seeing Harper wandering around backstage at Bath, Page approached him and asked to be shown how he played an instrumental from his first album, Blackpool.

“So I played it for him,” Harper remembers, “and he said: ‘Thanks very much.’ The only thing I thought as I watched him leave was: ‘That guy’s pants are too short for him.’”

It wasn’t until he saw Zeppelin play that evening that he realised who Page was. “During the second song [Heartbreaker], all the young women in the crowd started to stand up involuntarily, with tears running down their faces. It was like: ‘Jesus, what’s happening here then?’ In the end you knew you’d seen something you were never going to forget.”

Although neither of them knew it then, it was also the start of a long relationship between the two guitarists, with various Zep members appearing at Harper shows and Harper opening occasionally for Zeppelin. Nevertheless, he was taken aback some weeks later when he discovered his name on the next Zeppelin album.

“I went to their office one day and Jimmy said: ‘Here’s the new record.’ ‘Oh… thanks,’ I said, and tucked it under my arm. ‘Well look at it then!’” I discovered Hats Off To Harper. I was very touched.”

As he should have been. Over the next few years, that one track would introduce the perennially unsuccessful Harper to millions of album buyers around the world. “As far as I’m concerned,” Page explained, “hats off to anybody who does what they think is right and refuses to sell out.”

Or as Plant would later jokingly recall: “Somebody had to have a wry sense of humour and a perspective which stripped ego instantly – [and] we couldn’t get Zappa.”

Back at Headley Grange, Led Zeppelin continued honing their new material. Eventually there would be 17 near-complete tracks. To the acoustic-based material from Bron-Yr-Aur they now added Hats Off To (Roy) Harper, a piece of spontaneous combustion initiated by Page one night, inspired by some frenzied slide-guitar channelling of Bukka White’s Shake ’Em On Down (credited on the sleeve to ‘Charles Obscure’).

There was also Gallows Pole, a rollicking reinvention of a centuries-old English folk song called The Maid Freed From The Gallows, a striking contemporary version of which Page remembered fondly from the B-side of a 1965 single by Dorris Henderson that she’d dubbed Hangman, and which had stuck in his mind.

There were also a handful of electric, more obviously Zep-sounding tub-thumpers like Immigrant Song, Celebration Day and The Bathroom Song (so called because everyone said the drums sounded like they had been recorded in the bathroom), later changed to Out On The Tiles. Plus the foundation of what would become one of their finest ballads, the exquisite blues Since I’ve Been Loving You, begun at Olympic during the same truncated sessions that produced the original electric Jenning’s Farm. The band had played a shorter, tighter version live at Bath, but it wasn’t until now that they’d tried to finish it.

That said, the genesis of what was destined to become one of Zeppelin’s most famous tracks can again be fairly clearly pinned down to an earlier, typically unaccredited blues jam by Moby Grape titled Never. As the Grape remain one of Plant’s favourite San Francisco groups of the period, it’s inconceivable that he wasn’t already acquainted with Never. Indeed, the opening lines of Since I’ve Been Loving You – ‘Working from seven to eleven every night, it really makes life a drag, I don’t think that’s right’ – are almost identical to those on Never, which go: ‘Working from eleven to seven every night, ought to make life a drag, yeah, and I know that ain’t right.’

With Plant also displaying his new Van Morrison and Janis Joplin influences on the scatted vocal amid the sound of John Bonham’s squeaking bass-drum pedal and John Paul Jones’s jazzy bed of keyboards, while playing the bass pedals of the Hammond organ with his feet, all it needed to round it off was a spine-tingling guitar solo from Page.

The tape op at the session was a young guy named Richard Digby Smith. “I can see Robert at the mic now,” he later recalled. “He was so passionate. Lived every line. What you got on the record is what happened. His only preparation was a herbal cigarette and a couple of shots of Jack Daniel’s… I remember Pagey pushing him: ‘Let’s try the outro chorus again, improvise a bit more… There was a hugeness about everything Zeppelin did. I mean, look behind you and there was Peter Grant sitting on the sofa – the whole sofa.”

In an effort to try to complete the album, by now they had abandoned Headley in favour of the more polished surrounds of Island’s No. 2 studio at Basing Street in Notting Hill Gate. It was during these sessions that the first rough recording of another new song, No Quarter, written by Jones, was etched out.

All other considerations went out the window, though, as Page battled to come up with a suitable solo to finish off Since I’ve Been Loving You. But by the time their US tour began in Cincinnati on August 5, the album still wasn’t finished and Page was left with no option but to repeat the gruelling process that had characterised the previous summer’s US tour, jetting off to the studio between shows.

Fortunately he was able to call on his old friend Terry Manning at Ardent Studios in Memphis for help. “I’d pick Jimmy up at the airport and drive him straight to the studio to begin work,” Manning recalls. “Peter always accompanied Jimmy too. No one else, though. I think Robert came in for one day, Bonham came in for one. That was it.”

Manning remembers editing “a lot” out of Gallows Pole and Page trying – and repeatedly failing – to find the right solo for Loving You. “In the end Jimmy accepted that the demo solo done in England wasn’t going to be bettered, and so that was the one they eventually used. Listening back now, it’s my all-time number-one favourite rock guitar solo. We took three or four other takes, and tried to put takes together and come up with something, and they were all great. But there’s something magic about that one take [he did], that stream of consciousness.”

Page worked alone with Manning on the mix of the album. Manning says the much looser approach – the tape echo at the start of Immigrant Song, the wayward segue of Friends and Celebration Day, the occasional voices you can hear in the background, what a quarter of a century later would be called ‘lo-fi’ – was “all thought-out, not accidental at all”.

It was this aspect, he says now, that demonstrated to him what “a really brilliant producer” Page was.

“Not to demean or cast any aspersions,” he adds, choosing his words carefully, “but I think he harmed himself perhaps in a few ways later on. But at that particular time, the very early days, Jimmy was an incredibly insightful, true musical genius, in my opinion – and I’ve seen a lot of musical people. I would say that very little happened by accident. When it says ‘produced by Jimmy Page’, it seriously was.

“He asked me: ‘What do you think about leaving the beginning of the Celebration Day thing on [referring to the moment when Bonham can be heard shouting ‘Fuck!’]?’ No one ever seemed to pick up on it. But he said: ‘That’s not why I wanna leave it, not cos that’s cool. I like the sonic texture of everything. I like the feel that you’re really there.’ We really talked all that through.”

It was also Manning that Page would ask to help master the album. With albums produced, mixed and largely made on computer these days, mastering a vinyl record is almost a lost art. Back in 1970, though, it was still one of the most crucial parts of the recording process.

Using a lathe to transfer the sound from acetate on to vinyl, great care and an even greater set of ears were essential. Page and Manning were well aware that over the years, many potentially marvellous albums had been ruined because of poor technique at the mastering stage, and they approached the job with great seriousness. That is, until the final moments, when adding the usual catalogue numbers that would be stamped onto the run-out groove of the finished record.

“Working with Big Star, we had added some messages of our own on there,” Manning says. “I mentioned this to Jimmy and said: ‘Anything you wanna write?’ And he said: ‘Ooh, yeah…’”

Due to the enormous quantities of copies the pressing plant knew they would need to fill the advance orders alone for Led Zeppelin III, they had requested two sets of masters – not unusual for the biggest-selling American acts in those days. As a result, Page would come up with four separate ‘messages’, one per side of each master.

“We’d been talking about the Aleister Crowley thing,” Manning says. He said: ‘Give me a few minutes.’ And he sat down and he thought and he scribbled some things out, and he finally came up with ‘Do What Thou Wilt Shall Be The Whole Of The Law’ and ‘So Mote It Be’ and one other one which I’ve forgotten.”

I suggest perhaps either ‘Love Is The Law’ or ‘Love Under Will’, Crowley’s other two most famous maxims. “I suspect the latter,” Manning replies. “Sounds the most familiar.”

Released on October 23, 1970, two weeks after its release in America, Led Zeppelin III was already at No.1 in the US by the time it went on sale at home in Britain, where it would also top the chart. Nevertheless, it was destined to become one of Zeppelin’s most overlooked albums, misunderstood and largely reviled by the critics.

Even the fans seemed confounded. And although the album would eventually sell in millions, it remains one of the comparatively weakest sellers in the Zeppelin canon. Indeed, by the start of 1971 it had all but disappeared from the charts, while its more popular predecessor maintained a steady presence in both the US and UK Top 40s.

But if many were left nonplussed by the unexpected change in musical direction, the same critics who had previously attacked them for being shallow peddlers of roisterous clichés now accused them of daring to undermine such perceptions by singularly failing to repeat the trick.

At best they assumed the band had been unduly influenced by the recent success of Crosby, Stills & Nash, whose remarkable debut album had seen a seismic shift in critical opinion on where rock was – and should – be heading at the dawn of the new decade. It was a charge Page, in particular, whose background in acoustic roots music was well-established long before it became the fashionable sound of southern California, was furious over.

“I’m obsessed – not just interested, obsessed – with folk music,” he said, pointing out that he’d spent many years studying “the parallels between a country’s street music and its so-called classical and intellectual music, the way certain scales have travelled right across the globe. All this ethnological and musical interaction fascinates me.”

But no one was listening. Instead the critics screamed betrayal. Under the headline ‘Zepp weaken!’ Disc & Music Echo typically enquired: ‘Don’t Zeppelin care any more?’ There were occasional flashes of insight from the press. Lester Bangs – who had previously chastised Zeppelin for their “insensitive grossness” – wrote in Rolling Stone: “That’s The Way is the first song they’ve ever done that’s truly moved me. Son of a gun, it’s beautiful.”

According to Terry Manning, however, Page had anticipated such reactions. “He was quite apprehensive but quite determined. We spoke of these matters as we were in the studio completing it. He would say: ‘This is so different, this is going to shock people.’ And it did.”

“I felt a lot better once we started performing it,” Page told Dave Schulps in 1977, “because it was proving to be working for the people who came around to see us. There was always a big smile there in front of us. That was always more important than any poxy review.”

With an irate Page refusing to explain or make excuses to the press in 1970, it was left to Robert Plant to defend the album. “Now we’ve done Zeppelin III the sky’s the limit,” he told Record Mirror. “It shows we can change. It means there are endless possibilities and directions for us to go in.”

It was an entirely prophetic statement, as the next Zeppelin album would demonstrate in no uncertain terms. But that was still a year away, and for now the band were forced to live through the first dip in what until then had been a steady upward surge of their commercial fortunes. By the start of 1971 ‘Zep to Split’ stories were even beginning to pepper the British music papers.

But if Led Zeppelin III polarised opinion, long-term it went a considerable way to cementing their reputation, confounding expectations and proving there was more to them than simply being the ‘new Cream’ they had started life as.

Instead of more wall-shaking, heavy rock classics, the third Zeppelin album should be looked at now as the first convincing marriage of Page’s fiery occult blues and Plant’s swirling Welsh mists. It was the first serious proof of the band’s ability to move beyond the commercial straitjacket that would eventually leave contemporaries like Black Sabbath and Deep Purple marooned in a creative cul-de-sac, churning out copycat hits until they finally ran out of steam, key members came and went, and their reputations would be sealed forever as second-rung niche acts, truly loved only by heavy metal fanatics.

Besides, with bands like Sabbath now doing the job for them – “We used to lie on the floor of the rehearsal room, stoned, listening to the first two Zep albums,” recalls Sabbath’s Geezer Butler, who admits that his band’s most famous song, Paranoid, “was just a rip-off of Communication Breakdown” – the determinedly non-metallic direction of the new Zeppelin material was, in retrospect, not only a brave move but also an exceptionally shrewd one.

As Terry Manning says: “None of it was accidental. Jimmy knew they could not be more than the greatest heavy rock band if they didn’t expand into new avenues, into more than just beating you on the head with a riff. You take a band like The Beatles, or Pink Floyd, the kind of bands that kids of fifteen love today as much as the kids of thirty or forty years ago, and they sound totally different from their first album to the middle of their career to the end of their career.

“And Jimmy knew that. He wanted to be more. The first two Zeppelin albums are quite different from The Yardbirds. He wanted to keep going, keep expanding. He would talk about rhythms, and people like Bartok, Karl Heinz Stockhausen or John Cage. He was totally into Indian classical music, Irish folk music, all sorts of things.”

That would become ever more clear on subsequent Zeppelin albums, where Page’s fondness for such seemingly disparate musical bedfellows as funk, reggae, doo-wop, jazz, synth-pop and rockabilly could be felt amid the symphonic slabs of rock.

For now, the third album showcased what Page describes as “my CIA”. That is to say, “my Celtic, Indian and Asian influences. I always had much broader influences than I think people realised, all the way right through, even when I was doing [session] work. When I was hanging around with Jeff [Beck] before he was in The Yardbirds, I was still listening to all different things.”

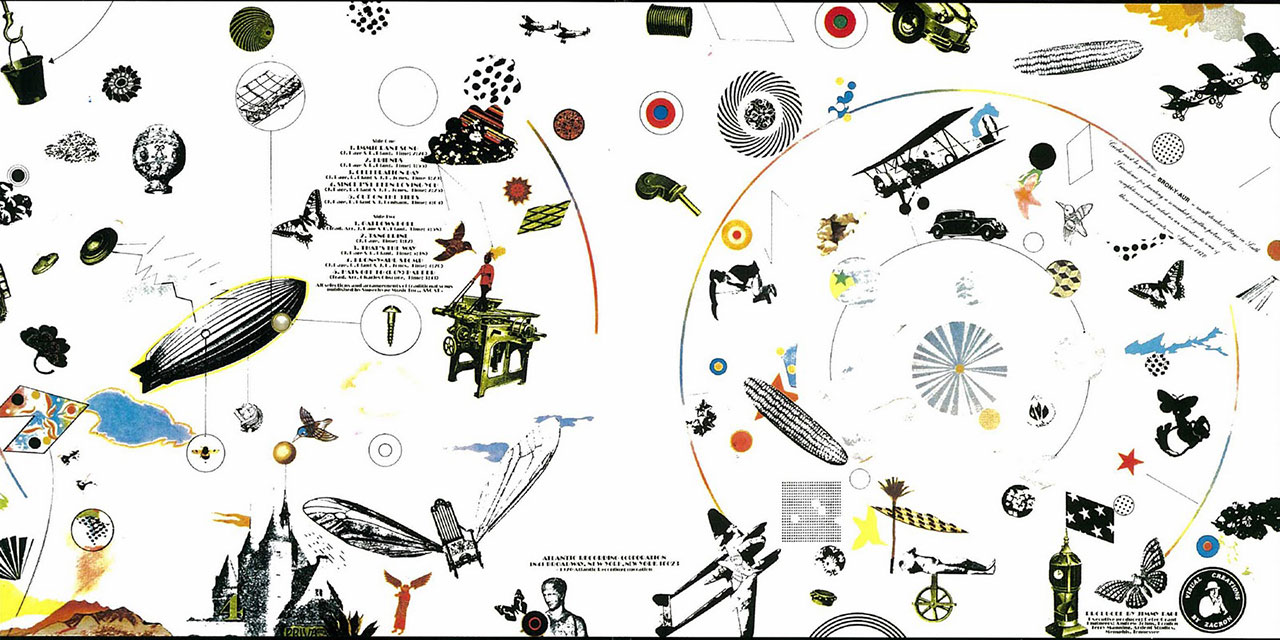

As if to add insult to injury, the gatefold sleeve of the third album was often more positively reviewed than the music inside. Designed by an old college pal of Jimmy’s who liked to go by the name of Zacron, then a tutor at Wimbledon College Of Art, the end result was a self-consciously ‘surreal’ collection of seemingly random images – butterflies, stars, zeppelins, colourful little smudges – on a white background.

The most striking element was a rotatable inner disc card, or volvelle, based on crop rotation charts, which when turned revealed more indecipherable sigils and occasional photos of the band, peeping through holes in the outer cover. Critics cooed, but it veered away drastically from what Page had actually asked for, and was more to do with Zacron’s own taste, rotating graphics being a signature of his work since 1965.

Zacron later recalled Page telling him: “I think it is fantastic.” But Jimmy told Guitar World in 1998: “I wasn’t happy with the final result.”

Zacron had got far too “personal” and “disappeared off with it… I thought it looked very teeny-bopperish. But we were on top of a deadline, so of course there was no way to make any radical changes to it. There were some silly bits – little chunks of corn and nonsense like that.”

Out on the road, the band were still going from strength to strength, with whatever acoustic subtleties employed on their new album sacrificed in concert for all-out rock assault. With Immigrant Song becoming another Top 20 single, reaching No.16 during a 13-week run on the Billboard chart, their 1970 summer tour of the US was their biggest yet, topped off with two sold-out three-hour shows at Madison Square Garden on September 19 and 20, their first time at New York’s most famous venue.

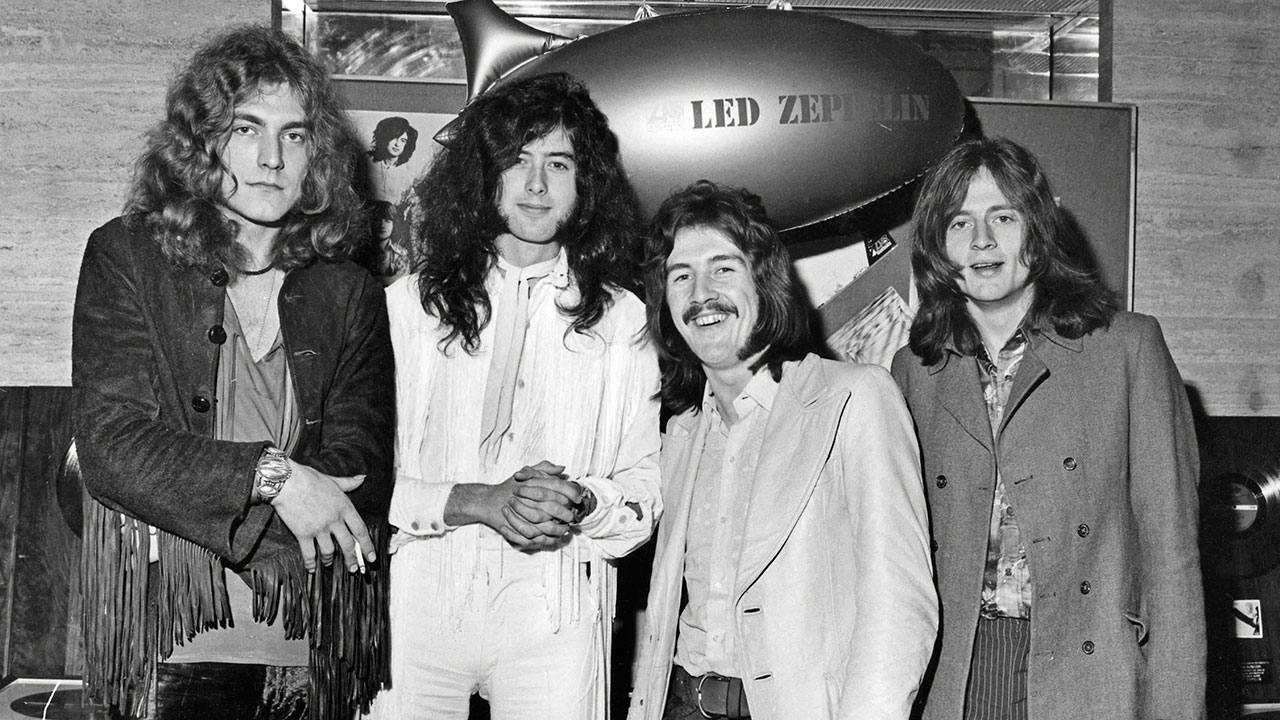

The same month, they were voted Best Group in the annual Readers’ Poll in Melody Maker – the same music paper that had slated Zeppelin III for “ripping off” Crosby, Stills & Nash. The first act for eight years to oust The Beatles from the top spot in what was then the UK’s most prestigious music magazine, Zeppelin returned to London for a special reception where they were also presented with more gold discs.

Yet for all the band’s public defiance, and Led Zeppelin III’s not inconsiderable sales, behind the scenes there was a palpable sense of disappointment when the album slipped unobtrusively from both the UK and US charts within weeks of topping them, at a time when Led Zeppelin II was still riding high around the world.

Used to fighting fires, Peter Grant moved swiftly to reassure Jimmy Page that no one at Atlantic, certainly, was perturbed by this disappointing downturn in events. The album had still sold more than a million copies in the US and had gone gold (for advance orders of more than 100,000) in the UK – the sort of figures they’d have been throwing lavish parties to celebrate a year before. The fact that the second album had sold more than five times that amount in the preceding 12 months was, if anything, a freak result, he argued, not the kind of thing one should expect every time Zeppelin released a new album.

Nevertheless, there were tensions over at Atlantic’s Broadway offices. Relatively speaking, Led Zeppelin III had been a commercial failure. The feeling – though politely disguised in earshot of Page, if not Grant – was that the band had shot themselves in the foot by releasing something so radically different from the winning formula established by their first two albums.

In order to appease both sides, Grant suggested the band take the rest of 1970 off. That is, abort their plan to tour Britain over Christmas and instead return to the studio. Although he was reluctant to spell it out to Page, Grant knew it was essential that the band get another, hopefully more representative album out as soon as possible. By going into the studio now, he argued, they would be in no rush this time, either.

So concerned was Grant, in fact, that he turned down an offer of a million dollars for a New Year’s Eve concert to be performed in Germany and linked by satellite to a large chain of cinemas in America. The reason he said no, he later explained, was because “I found out that satellite sound can be affected by snowstorms”.

In reality, he was more concerned for Led Zeppelin’s career as recording artists. He felt sure their next album would be make or break.

For Peter Grant and Led Zeppelin, there were more than a mere million bucks at stake in whatever they did next. There was their entire all‑that-glitters-is-gold future.

Eddie Kramer's guide to Led Zeppelin's Houses Of The Holy

Peter Grant interview: Life with Led Zeppelin and the death of John Bonham

Led Zeppelin: The Story Behind Led Zeppelin II

Led Zeppelin Albums Ranked From Worst To Best – The Ultimate Guide