Is Spotify killing the music industry?

Roger Waters isn't happy. The industry isn't happy. How long will fans continue to value music now it's streamed for free? And how the hell did we get here?

There’s a whole generation who’ve “grown up who believe that music should be free,” said the famously sullen Roger Waters to The Times recently. “I mean, why not make everything free? Then you could walk into a shop and say ‘I like that television’ and you walk out with it. No. Somebody made that and you have to buy it! ‘Oh, I’ll just pick up few apples.’ No. Some farmer grew those and brought them here to be sold.”

Equating the downloading of a snide MP3 with actual shoplifting is not a new argument – nor is it directly comparable as digital files are, by their very nature, infinitely replicable at no incremental cost, unlike a TV or an apple. But Waters does strike here at the very heart of an issue that the creative industries are having an increasingly toxic relationship with; namely that of free content – be it official (on YouTube, Vevo or Spotify) or unofficial (insert the name of your preferred P2P or torrent site here).

“I equate ‘free’ with the decline of the music business,” Doug Morris, head of Sony Music, indignantly told Hits Daily Double in March. “In general, free is death.”

He was not talking about “free” in the pirated sense. He was talking about free on streaming services like YouTube and Spotify. Universal Music, the biggest label in the world, came out with similar views at the same time, suggesting a significant change in business temperature that will profoundly affect how music is made available online.

A year ago, the major labels were flag-wavers for “free” – seeing YouTube and Spotify as places where ads could be placed around free music and they could share in that. What caused this massive about-turn? In short, the numbers were not adding up; or, more specifically, not adding up quickly enough. Or possibly Apple forced their hands – more of which in a moment.

Any historian of the record business, however, will tell you this label flip-flopping around free is nothing new. Plus, as the French say, ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

In the 1920s, the boom in radio set sales looked like it was going to kill record companies who were using discs to help sell their own player hardware. Who needed records if radio played music for free?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Radio in the 1930s: the Spotify of its day?

Reacting counter-intuitively, the canniest labels sent out free records to DJs. Rather than seeing radio as killing them, they saw it as a way to advertise their recordings. Record sales, helped by the boom in jukebox sales and a less turbulent economy in the 1930s, soon grew again, turning what was initially seen as a huge threat into an unfurling opportunity. Record companies were saved.

They did the same trick in the 1980s with MTV, letting it play expensive promo videos for free as it would help sell singles and albums. They forgot to factor in that MTV would also become rich and powerful as a result. The good thing, the labels reassured themselves, was that if they gave music away they did so on their own terms. That quixotic thinking was not to last.

All hell broke out in the mid-1990s with the arrival of file-sharing technology. Initially a geeky endeavour, the development of Napster by Shawn Fanning in 1999 blew the lid off everything. A century of people having to pay to hear the music they wanted when they wanted across a variety of formats was instantly vaporised.

Fighting the Napster wars: Metallica’s Lars Ulrich, Byrds’ guitarist Roger McGuinn, and Napster CEO Hank Barry appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2000.

Stephen Witt’s upcoming book, How Music Got Free, is a fascinating history of this technological perfect storm (development of the MP3, file-sharing software offered for no cost, mass broadband adoption) that pushed the concept of free in front of people who would never have previously considered it as an option. This “normalised” the notion of free in relation to music and the ripple effect has just spread out wider to cover all creative forms.

The record business stumbled into the 21st century with all certainties gone. For the first time, they were no longer competing against each other for market dominance – they were competing with both the political philosophy and the economic reality of free.

The psychological impact on consumers is still, 16 years later, being unpicked. If everything is theoretically free, it is only your conscience that is stopping you turning that theory into practice. This has bled into all corners of society as the culture of “exposure” replaces the culture of being paid. Bands are commonly asked to play shows, give away songs and have their music used in ads for free, with the nebulous promise that, somehow, they can “leverage” the “profile” it gives them.

Roger Waters is merely the latest to join a growing choir of major acts refusing to go along with what they see as a dangerous race to the bottom.

Windmilling into Spotify in 2013, Radiohead’s Thom Yorke described the Swedish company as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse”. Despite the oxymoronic nature of this statement (a corpse is already dead so it can’t be “dying”), Yorke was the first major act to so publicly attack legal streaming for the minuscule royalties that get paid through to artists.

_June 2013: Spotify employees in New York gather to hear mayor Bloomberg announce the creation of 130 new jobs at the company. _

The issue zoomed towards its event horizon at the end of 2014 when Taylor Swift, arguably the biggest pop star in the world right now, pulled all her music from Spotify. “With Beats Music and Rhapsody you have to pay for a premium package in order to access my albums,” she told Time magazine. “And that places a perception of value on what I’ve created. On Spotify, they don’t have any settings, or any kind of qualifications for who gets what music. I think that people should feel that there is a value to what musicians have created.”

In this growing culture of “free”, getting paid is no longer an entitlement. It’s discretionary.

Sadly, in a time of apocalypse, rather than everyone band together for the greater good, a toxic survival instinct starts to kick in, like the twisted end of Animal Farm where all animals were deemed equal but some decided they were more equal than others.

The most recent example of that was Garbage, in April, finding themselves at the sharp end of the free debate when they had the unenviable position of being the ones to break photographer Pat Pope’s resolve. In short, he had photographed them over the years and they all got along swimmingly. The band’s management company sent him a pro forma contract to use some pictures he had taken of the band, and whose copyright he still controlled, for a book the band were publishing about their career. The problem was the absence of a budget.

He snapped, having received hundreds of similar requests a year, and published an open letter to the band on his Facebook page, explaining why this was, frankly, not on. “No, you don’t have my permission to use my work for free,” he wrote. “I’m proud of my work and I think it has a value. If you don’t think it has any value, don’t use it. I’m saying no to a budget that says you can take my work for free and make money out of it.”

The band responded to explain their position, arguably turning a bad situation into a code red one. Some accused Pope of greed; others saw him as a brave defender of the creator’s right to get paid. His case is by no means an anomaly. It’s just the latest battleground in this battle over free which is really a battle about entitlement: the creator’s entitlement to get paid for their work versus a broader presumed entitlement that, just because it’s digitised and online (or has been paid for before for use in a different context), it’s fair game from anyone to pick and use as they see fit.

Garbage, in saying they had no budget to pay for Pope’s pictures (and presumably the pictures of the others who did, consensually, agree) could have taken it to Kickstarter like Amanda Palmer and Neil Young (for his high-def audio service Pono). Or Indiegogo. Or PledgeMusic. Or Patreon. Or any of the other crowd-funding platforms that exist precisely to help bands with cash flow issues get their latest projects up and running. They all, crucially, encourage among fans a culture of paying. You want some stuff from your favourite act? Sure, but you’re going to have to put your hand in your pocket. It’s a less grubby form of busking and is an important pocket of resistance against the dead-eyed march of free.

Garbage in 2002 (Pic: Getty Images/Mick Hutson)

Free is the default price point of music on the internet – songs, photos, journalism, lyrics, guitar tabs are all available for no cost to the user, except in exchange for watching a few ads. These are also ads that, with judicious use of ad-blocking software, can be removed, meaning no one gets paid.

Spotify, when it arrived in 2008, wanted to invert free and make it a way to hook users and push them to become subscribers – offering a limited free version of its service and a £10-a-month paid version that offered a better user experience (no cap on how many songs you could play, no ads, offline storage on mobile and so on). This “freemium” model is common in other businesses, notably gaming apps, and was the subject of former Wired magazine editor-in-chief Chris Anderson’s second book, Free: The Future Of A Radical Price in 2009, after his first book bequeathed us the theory of the long tail.

Spotify now has 60m users, 15m of whom are paying, meaning it has a 25% conversion rate. Labels, however, are starting to question this as a long-term strategy and they want Spotify to convert free users into paying users at a much faster rate. This open war on free in general comes at a time when the labels’ licences with Spotify are up for renegotiation. Which is convenient. And could see a Mexican standoff here. Spotify sees free as a recruitment channel. The labels see it as death by a thousand cuts. Who will blink first?

This has all taken a twist worth of a pulp novel in recent days with The Verge reporting that Apple is attempting to strong arm the major labels into shutting off the free side of Spotify and YouTube. It is doing this so as to give the imminent re-launch of Beats Music, which Apple acquired as part of its $3bn acquisition of Beats last year, a serious chance in the streaming market as the company behind iTunes looks to, a decade on, move its diminishing downloads business into the brave new world of streaming. The logic runs that Apple regards free as the biggest obstacle to Beats being a success and so is using its not inconsiderable muscle to get the major labels to throw licensing spanners into its competitors’ works.

It is interesting that Apple regards other services offering music for free as putting its own business objectives on the back foot when it is not totally opposed to the philosophy of free. Exhibit A: handing out promoted iTunes tracks each week for years. Exhibit B: giving U2’s last album, Songs Of Innocence, away to all its customers last year on its day of release, whether they wanted it or not. Again, the spectre of George Orwell looms with the doublethink on display here: “Free is bad but our free is good.”

Free is everywhere, and is often offered up voluntarily by creators, where it has become not so much a pandemic as a construed as a basic online entitlement. Free is the great disruptor, unhooking culture from commerce and many – most notably academic and activist Lawrence Lessig, who feels copyright and trademark lockdowns are bad for culture and democracy – see this as democratically liberating, breaking open the narrow channels of cultural production monopolised by a handful of profit-oriented corporations.

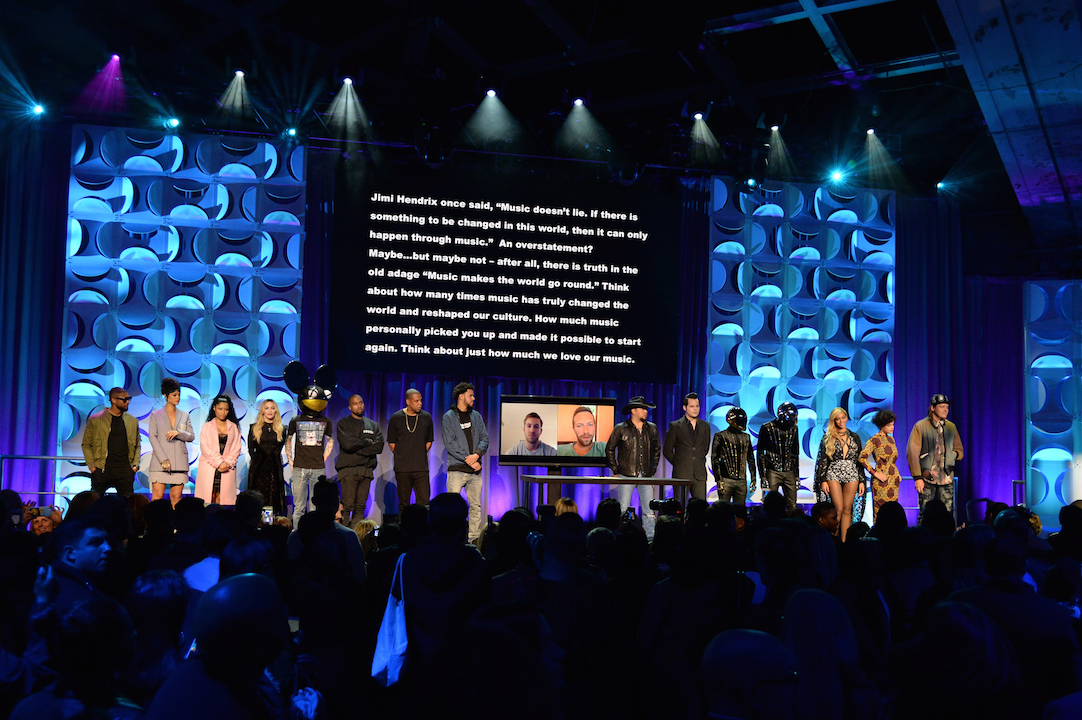

Millionaire musicians gather to offer an alternative to Spotify, as Tidal launches beneath suitably appropriate words from Jim Hendrix.

In his 2004 book, Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology & The Law To Lock Down Culture And Control Creativity, Lessig puts forward his argument around free which is as much about semantics as it is about political positioning. “We come from a tradition of ‘free culture’ — not ‘free’ as in ‘free beer’ […] but ‘free’ as in ‘free speech’, ‘free markets’, ‘free trade’, ‘free enterprise’, ‘free will’, and ‘free elections’,” he argues. “A free culture is not a culture without property, just as a free market is not a market in which everything is free. The opposite of a free culture is a ‘permission culture’ – a culture in which creators get to create only with the permission of the powerful, or of creators from the past.”

There is no cultural hierarchy now, runs the theory. Everyone is a creator. But being a creator and being paid have long stopped being synonymous.

What will all this mean? Record companies will still continue to exist, but they’ll be squeezed down in terms of the number of acts they sign. More artists will try the DIY route but only a percentage will be able to make a proper living from music alone. Labels and artists will still, ever the optimists, try to harness free in a way that suits them but which could only exacerbate this free/paid tension further.

Streaming, either paid or free, is going to become the dominant way people consume music and that is going to seriously affect the way money flows into the record business (and, thereafter, to artists). Despite the claims made on vinyl’s behalf, it will stay a niche format. The CD will crumble further and the MP3 will become a curio of the past, like the cassette or the MiniDisc. That all means that making a living out of recorded music is going to become harder – especially if acts are supposed to exist on the promise of repeat micro-royalties spread over decades as opposed to upfront payments typical of the vinyl and CD (and download) age.

Not every artist, of course, gets the vapours when confronted with the idea of “free”, seeing the giving away of music as a means to raise their profile and make money elsewhere, such as playing live or DJ-ing. Pretty Lights, Moby and even (oh, yes) Thom Yorke have all used the Bundle option on BitTorrent, either giving everything away or offering just a handful of tracks while encouraging fans to click through and buy the premium bundle.

Free, however, has such momentum it will only grow in power – either actually funded by ads or through a subscription so it become a utility like a mobile phone bill that’s paid automatically but, in doing so, stops feeling like a treat to the consumer. The knock on effect on how the public attaches both a monetary and a cultural value to music is still the great unknown.

Oscar Wilde famously described a cynic as “a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing”. In the digital age, we might have everything for free, but no one has fully worked out the cost.

Eamonn Forde was paid for writing this article. The photos used throughout were also paid for. You’re reading it for free.