Bruce Dickinson would like you to know that when it came to writing his autobiography, What Does This Button Do?, he didn’t need any outside help. “People ask: ‘So who was your ghost writer?’ and I go: “Actually, I did it myself,’” he told us proudly. “I physically wrote 180,000 words, and all of it was on WH Smith pads in actual handwriting, proper old-school.”

Writing an entire book by hand is a very Bruce Dickinson thing to do. The Iron Maiden singer is seemingly a man who can turn his hand to pretty much anything: flying aircraft, fencing, fronting one of the most successful bands of the past 50 years. The exception is swimming: “I am one of nature’s sinkers,” he said.

What Does This Button Do?, released in 2017, is a genuinely fascinating and funny look back at Dickinson’s life. From his early days growing up in the Nottinghamshire mining town of Worksop (where he was raised by his grandparents until the age of six) to his roller‑coaster 40-plus-year music career, it paints a candid picture of a life well lived.

In the year of its release, Classic Rock sat down with the singer for an in-depth conversation about his life, work and everything in between. This is what he had to say.

Your parents were often absent during your early years – they were on the road with a performing dog act. Were you always destined to follow them into show business?

"Even before I knew properly who my parents were, I was after a pair of angel wings in the school nativity play. I wanted to be the person wearing them. My school reports were always depressingly similar: 'Has not fulfilled his good potential, would do better if he didn’t play the class clown 24 hours a day.'"

You paint a vivid picture of your school days: bullying, regular beatings from the teachers. It sounds pretty horrific, but did it also make you the man you are?

"It’s like the opening of the book says: everything moves in mysterious ways. You’ve got no idea where you’re going to end up. You have to take things as they come. The one thing I am, I suppose, is stubborn. I don’t fall over. Or if I do, I get back up."

Some of the teachers you mention were fairly despicable. You write about some of the canings they dished out as if there was a sexual, S&M-like element to them.

"The whole era was very strange. These were creepy, dirty old men, and it was thought to be normal and acceptable. The whole Jimmy Savile thing and the rest of it opened up a massive can of worms, because that stuff was socially acceptable. The sort of stuff you’d be banged up for now, and quite rightly. You have to pinch yourself and go: 'I’m really not living in the seventies any more.'”

Was there anything good about that time?

"There were a lot of brilliant things about the seventies, cos it was pretty disorganised and anarchic. But the flip side to that was that a lot of people got away with doing things that really weren’t so pleasant."

There’s one teacher, John Worsley, that you speak highly of. He introduced you to fencing. Did you stay in contact with him?

"I didn’t, but funnily enough I met his brother years later. Maiden were doing something in Florida in the middle of the eighties. There was this fencing competition in Fort Myers, and I ended up driving out there. I met this bloke called Worsley. I went: 'Worsley? John Worsley?' And he went: 'Yeah, that’s my brother.' Fencing is a very, very small world."

Do you still fence?

"Yes, but I hardly have any time to go near it. I keep wandering around and looking at all my kit, going: 'It’s getting a bit rusty now.' [Laughs] Like me."

Have you still got it in you, though?

"Absolutely. If I had a good run up, where I didn’t have other stuff going on, I’d be good. I love it. It’s really good fun. It’s cathartic and you get out there and have a yell and a scream but nobody dies."

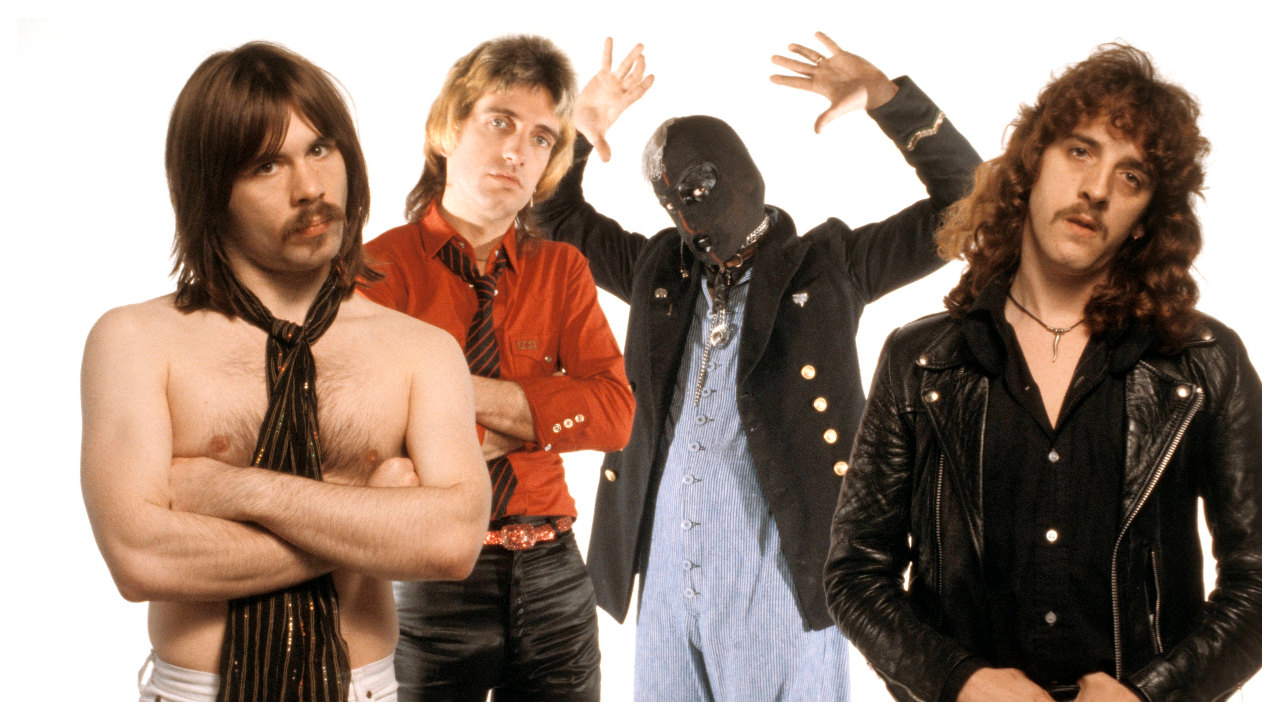

In his late teens, Dickinson moved to London, ostensibly to study history at university but in reality to pursue a career in music. After a few false starts, most notably in pub-rockers Speed, later called Shots (the highlight of their career was Dracula, a homage to the literary vampire that was more Carry On Screaming than it was Bram Stoker), Dickinson ended up as frontman with the NWOBHM band Samson, where he traded under the name Bruce Bruce and sported an impressive moustache.

If you met the twenty-year-old Bruce Dickinson in the pub, what would you think?

"Gosh. Light the blue touch-paper! I don’t know what’s going on with that kid, but something is going to happen. He’s either going to end up doing what he says he’s going to do or he’s going to end up in jail. Or at the bottom of the river."

You make no secret of your spliff-smoking days in Samson, but then you stopped.

"Had Samson not been such a bunch of potheads, I wouldn’t have bothered at all. I was like: 'I’ve done the cannabis now, I don’t see any point in taking it further.' Nothing else happens. All that does happen is that people seem to slow down and eat a lot."

Did drugs get in the way of your ambition?

"No, not really. They just didn’t do anything for me creatively. The first time, you’re like: 'Whoa, what’s all this about?!' But I soon realised I could get the same effect just by wandering around and using my imagination. I thought: 'I don’t need to smoke something to go and imagine that.' It was a nice awakening, but once your consciousness is awake, you go: 'I don’t need that any more.' It’s like writing really trippy lyrics – I’ve never taken an acid trip in my life. I’ve never eaten a mushroom or had anything remotely hallucinogenic. Everything comes out of my imagination."

You always avoided cocaine. Why? It must have been freely available.

"I never got cocaine. I got speed, because it made you run around really fast. But then it also made you feel absolutely shit. As far as cocaine is concerned, people get mashed and then sit there with the most stupid gibberish coming out of their gobs for hours and hours on end. It’s just tedious at best, and at worst it turns people into paranoid nutcases. So I’ve got no time for cocaine whatsoever. And obviously anything resembling depressives, I just don’t get. I don’t get why someone would want to shut reality off. Cos reality is brilliant."

You write about Iron Maiden’s success in the eighties in the book, but also about the hard work involved. What does the pie chart of ‘Fun’ versus ‘Not Fun’ in that period look like?

"By and large we were working so hard, it was Groundhog Day: the venues get bigger, the venues get bigger, the venues get bigger. The roller coaster never stopped going down. At one point, Rod [Smallwood, manager] had us doing nine shows, one day off, eight shows, one day off. I said: 'You can’t run human beings like that, they’ll fall over.'

"We were always arguing with Rod about making life more comfortable for ourselves. At one point, halfway through a tour, the stage manager literally sleepwalked off the stage. We said: 'Don’t you think it’s about time we got a tour bus?' And he went [grudgingly]: 'Yeah, alright then.'"

But was the whole thing actually enjoyable?

"Of course it was enjoyable. The only thing you miss is any semblance of life outside it. That’s where it started to feel oppressive, especially towards the end of the Powerslave tour. You think: 'What’s the point of all this?' And it turns into the world’s biggest circular argument. 'What’s the point?' 'The point of it all is just to do it.' 'Well, there’s other things I want to do…'"

For Dickinson, there certainly were other things to do. In the book, he doesn’t hold back when talking about his growing disillusion with Maiden during the early 90s, and his subsequent solo career. The impression of that period, at least initially, is of a man who stepped out of a gilded cage, only to spend the next few years trying to escape his own shadow.

What was it like to leave Iron Maiden?

"It was like being a wild animal in a cage. They suddenly let you out and say: 'There you go, off you go into the jungle, feed yourself.' And you go: 'I’ve forgotten how to do that.' When I quit, everybody assumed I knew what to do, but I didn’t.

"It was a question of building it all up again. Most bands have the luxury of doing that when nobody’s bothered about them, so they make all these really goofy mistakes. I just happened to go and do the whole thing in public. In retrospect, I didn’t do a bad job of it once I’d got things in focus."

What do you mean?

"There were some great songs on [Dickinson’s first post-Maiden solo album] Balls To Picasso. The big Achilles heel was that there was no clear direction – that’s what the listening audience want. But even if I had come out with a clear direction I don’t think people were ready to listen anyway, because they were so shell-shocked at me leaving."

What did you learn about yourself during the years away from Maiden?

"I actually learnt a lot more about other people. The one thing that happens when you’re in a big, powerful rock band – as in, powerful in the media – is that you have all kinds of people who will protect you; all kinds of people who will hide bad reviews from you or make sure you don’t see that paper because it didn’t say nice things about you. I don’t think that’s very helpful. But when you leave the fold and you’re suddenly on your own, outside the protective pentagram, you see all these people queuing up to give you a good kicking, because they couldn’t when you were in Maiden. And you think: 'Really? Wow.'"

Did the negative reviews bother you?

"I was quite sensitive to reviews, especially if I thought they weren’t being fair. At the same time, I was never afraid of a critical review if it was honest and laid out reasons why."

When Blaze Bayley replaced you in Maiden, you sent him two bricks painted yellow.

"I saw an interview with him, and there was a line at the end where he said: 'I feel like Dorothy in The Wizard Of Oz.' I thought: 'That’s really sweet. I know exactly how you feel.' So I painted two bricks and sent them to him."

Did you ever see Maiden with Blaze singing?

"No. It was all a little bit fraught. The only time I’ve actually listened to the albums was when Steve [Harris] said: 'We need to go and record one of these songs.' I thought: 'Oh, how does it go, then? I’d better go and have a listen to it.'"

Blaze gave it his best shot.

"He did. Absolutely. Hats off. Full-on respect to him for that. His voice is very different to mine, and there was a point when he got the job where I thought: 'How the hell is he going to manage to do those songs? Maybe they just won’t do them.'

"I said to someone at the time: 'Why don’t they really do something off the wall and really outrageous? Get a woman! There’s some of these female Finnish vocalists kicking around, and they’ve got the most outrageous voices! Do something to really, really knock people’s socks off.' But I’d have been fucked then. I’d never have come back."

Dickinson did return to Maiden, of course, in 1999, helping to usher in a period of success that outstripped even that of the band’s 80s heyday. Since then he has diverted his energies into other areas, including flying (he’s a qualified commercial airline pilot, and famously piloted Maiden’s Ed Force One plane on several tours) and beer-making (he had hands-on involvement in launching Maiden’s signature Trooper beer). Even a potentially life-threatening diagnosis with head and neck cancer in 2014 was seen off with a characteristic combativeness.

You steer clear of politics in the book. You’ve tried a lot of other things, but have you ever thought of running for office?

"[Emphatically] No, no, no, no, no, It’s madness. No. I’ve got quite a few friends who are actually MPs of all shapes and sizes. And I’ve had my fair share of dealings with government agencies from the aviation side of things. And the one thing I’ve realised is that if you want to get anything done, don’t be a politician. It’s the civil servants who run the politicians, as they quickly realise when they get into office.

"We stand more chance of helping people out in Maiden by brewing beer and creating jobs, or taking a hundred and fifty people out on the road with us and giving them all jobs. We do a huge amount with Maiden."

How did your cancer diagnosis change your view of death?

"I’m a bit more philosophical about it now. Although I wasn’t at any stage… how can I put it… near death, I could certainly see it in the rear-view mirror. Death doesn’t really cross your mind much, unless someone has an accident or falls under a bus. As human beings we brush it off, especially if you’re at a relatively young age, full of piss and vinegar, running around like a lunatic. And then all of a sudden in comes Mr Death with his scythe, pointing and saying: 'I have come for you.' And you go: 'Oh fuck. Really? I’ve got things to do.' So suddenly you find yourself really getting on with that, living your life that bit more, doing the things you’ve got to do. I find I have less time for people who want to waste my time."