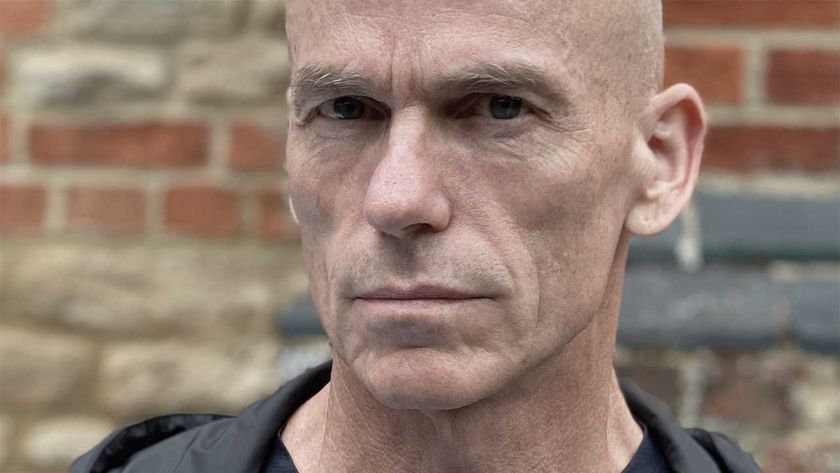

“I think it’s probably the best band I’ve ever had since the Mahavishnu Orchestra!”

John McLaughlin is clearly excited as he talks about the release of Black Light, his 18th album as a named leader in a recording career spanning more than five decades. It is, of course, understandable that a musician with an album to promote is bound to make great claims for his latest offering, but even a cursory listen to the record in question confirms he may well be right.

At the age of 73, having been intimately associated with the birth of jazz rock and fusion in the late 1960s through his work with Tony Williams Lifetime, and In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew with Miles Davis, the guitarist could easily be forgiven for opting to take things a little easier now. Yet McLaughlin’s trademark dexterity remains undiminished.

Crammed with dazzling themes and intense, expressive performances by Gary Husband (keyboards), Etienne M’Bappe (bass) and Ranjit Barot (drums), Black Light appears to back up his claim. “This particular band never ceases to amaze me with what they do. I’m standing there in the studio with them and they’re blowing my mind. It’s as good as it gets!”

An old saying goes that if you’re the best player in the band then you’re in the wrong band. It’s long been a tenet of McLaughlin’s practice as a developing musician that he seeks out those who can take his understanding and playing to another level. While there are some player/composers in the jazz and jazz rock spheres content to recruit skilled sidemen to execute their works, McLaughlin isn’t one of them. While it’s understood that the guitarist is unquestionably the de facto leader, The 4th Dimension band is most definitely not a collection of mere executants, but rather players possessing their own distinctive personality, both individually and collectively.

“My philosophy is that these guys are so great I need them to be who they are. They’re kicking me in the butt but that’s exactly what I need as a player. If somebody is provoking me in the right way – stimulating may be a better word – we need that extra push to get away from what we know and to enter into that special place where it all becomes spontaneous.

This particular band never ceases to amaze me with what they do. I’m standing there in the studio with them and they’re blowing my mind. It’s as good as it gets!”

“This pushing each other isn’t aggressive. In a way, I’m writing to provoke them to get something extra or unexpected out of them. It’s one thing to structure a tune with an arrangement but when it comes to the playing then we need to push and provoke each other in order to get to those places where we’ve never been before. That sounds like Captain Kirk, doesn’t it?” he guffaws.

As well as his new album, 2015 also marks the 40th anniversary of Visions Of The Emerald Beyond by the second incarnation of the Mahavishnu Orchestra. With an 11-piece group that included a string quartet and horn section, it also featured ex-Zappa violinist Jean-Luc Ponty and the phenomenally talented Narada Michael Walden on drums. The album distilled the symphonic ambitions of 1974’s Apocalypse into something more immediate.

Although it’s the first line-up of the group with Jerry Goodman, Jan Hammer, Rick Laird and Billy Cobham that took McLaughlin into the Top 30 album charts on both sides of the Atlantic, and which still receives plaudits for its fiery mix of blues, rock, jazz and Eastern modes, McLaughlin has no hesitation in citing Visions Of The Emerald Beyond as a high point in his output over the years. “It was such a special moment in my career,” he says.Eternity’s Breath, which opens Visions Of The Emerald Beyond, begins with the elements gradually coalescing from the drones and fluid notes oozing slowly into being until they suddenly erupt into flight with both speed and jaw-dropping precision, biting down into one of the band’s most memorable riffs. Closing the record, the track On The Way Home To Earth reverses that process of accretion as the entire ensemble, locked into a scorching finale, are eventually burnt up and discarded, leaving only a single yearning note from McLaughlin.

Despite sounding incredibly structured and deliberate, the final shape of the album was the result of a process far more intuitive than the listener might have ever imagined. “I haven’t the foggiest idea of what will start an album or what will end it,” admits McLaughlin. “The pieces evolve as they go in the studio and it’s really a matter of listening once everything is mixed. That’s really the first opportunity I have where I can sit down and listen and say what kind of rhythm an album will have. It’s a bit tricky sometimes to know what goes first and what goes last. It’s a very mysterious process – sometimes something special can happen when you make a record, and that album has it. It has a quality that even today I can’t quite put my finger on. It’s one of my all-time favourites.”

He sighs heavily, remembering the costs of running an 11-piece band on the road and the technical difficulties involved in ensuring the acoustic string quartet elements of the group were able to compete against the highly amplified sections of the bass, drums and keyboards. “These days it would be impossible because there’s no more record industry to support that kind thing.”

As the band eventually reduced down to a more manageable quartet, McLaughlin once again felt that burning need to look for other challenges. “By the end of 1975, really for my musical development and spiritual development, you could say, I had to let the Mahavishnu Orchestra band go because I wanted to concentrate on playing in Shakti with my Indian brothers,” McLaughlin says. “I got a lot of flak for that from my agent and record company. In America they were saying to me: ‘What are doing sitting on a carpet with those Indians? You’ve got a very successful jazz rock band!’ But I had to do it and I told them I’d accept the consequences. I ended up losing sales but at the same time I was happy. I just have to go where the music pulls me by the nose.”

While there’s much joy to be found in Black Light’s stridently vibrant music, that happiness is tinged with McLaughlin’s sadness at the loss of some of his fellow musicians, which is alluded too in the titles and the dedications. Panditji was written in honour of Ravi Shankar, with whom McLaughlin studied in the 70s, while El Hombre Que Sabia is for flamenco virtuoso Paco de Lucía, who died in 2014.

Inside I’m 29 years old but my actual body is a 73-year-old hippie – I’ll stop recording when I fall over dead!

“You know, me and Paco were supposed to record last year and we were going to do this as a duo. As Paco was particularly fond of this tune, I thought I should make an arrangement of it for the band. I miss him terribly.”

Then, by way of breaking the mood, he quickly adds: “Actually, I’ve just finished mixing a concert Paco and I did in 1987, which is finally going to be released. It’s taken me 28 years to convince a record company to put it out. It’s fantastic!”

However, McLaughlin’s normally upbeat mood and charismatic energy audibly falter when he talks about the dedication of Here Come The Jiis to U. Srinivas, the mandolin player who was one of McLaughlin’s partners in Remember Shakti, and who also died in 2014. Having previously divided his time between The 4th Dimension Band and Shakti, McLaughlin admits that the death of his close colleague hit him hard.

“Since we lost Srinivas last year I haven’t had the heart to replace him. I really don’t know what to do about it. Fourteen years we were playing together and he was so dear to me. There are plenty of great players in India but right now I don’t have the heart. Maybe later… I don’t know.”

On the question of his own mortality, he’s typically sanguine. “I’ll stop recording when I fall over dead!” he laughs again. “Well, inside I’m 29 years old but my actual body is a 73-year-old hippie! Until now, everything’s fine, but I know the machine is getting older. I’m very lucky because I keep fit and eat wise and I’ve given up all my bad habits over the years. I’ve already reached the Biblical age of three score and ten and so every day you have after that is a bonus.”

With more touring planned for The 4th Dimension Band in 2015, and a 2016 summer tour of Europe currently in the pipeline also, as well as a future project with Carlos Santana, Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter being talked about at the moment, McLaughlin is still looking to connect with music in a physical and spiritual way.

“When I was five years old, my mom played me Beethoven’s Ninth, the vocal quartet part, and it made my hair stand on end. I knew it was the music that did that. You have a total identification with the music – you’re part

of it and the music is part of you. That’s what made me want to be a musician. It still does.”

Black Light is out now on Abstract Logix. See www.johnmclaughlin.com for more information.