The Electric Light Orchestra came from the collision of two unique pop visions born in Birmingham’s beat group scene, which morphed into a cohesive game plan, then splintered to leave the world with ELO – and an eternal Christmas standard.

Of the pair, singer-guitarist Roy Wood was first to enjoy chart success after he joined the volatile Move, so named when members of Carl Wayne and the Vikings, the Nightriders and Mayfair Set moved together in late 1965 to form a Brummie supergroup, also comprising singer Wayne, bassist Chris ‘Ace’ Kefford, guitarist Trevor Burton and drummer Bev Bevan.

Steered by Moody Blues manager Tony Secunda, The Move brought old school showbiz outrage into the psychedelia starting to grip the country, sporting 1920s gangsters outfits and attracting attention in late 1966 with an explosive residency at the Marquee club, which expanded The Who’s auto-destruction into wrecking TV sets and cars.

Their set then mixed rock’n’roll standards with covers of West Coast bands such as Moby Grape and the Byrds but, after Secunda persuaded Wood to start writing songs, The Move shot to No.2 with the bad acid trip of Night Of Fear, which was built on sitars mutating Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. It was followed by I Can Hear The Grass Grow, another spangled drug anthem, before September’s Flowers In The Rain became the first chart single played on the BBC’s Radio One. This was despite the furore over Secunda’s promotional campaign, which saw Prime Minister Harold Wilson sue the band after postcards were circulated depicting him naked in bed with his secretary, Marcia Williams. The band forfeited all future royalties (a situation still in place) from the No.2 hit and fired Secunda.

After appearing on November’s legendary package tour with Hendrix, Pink Floyd and The Nice, The Move ignited the top three with Wood’s Fire Brigade (but when this writer witnessed them at that May’s NME Pollwinners Concert, they eschewed hits in favour of a glammed-up Wood exploring his newly acquired wah wah pedal on an epic version of Spooky Tooth’s Sunshine Help Me). Kefford had gone, after freaking out on acid, but the four-piece released their self-titled first album and marvellously autumnal number one Blackberry Way, which signalled Burton’s departure to form Balls with the Moodies’ Denny Laine and future Yes drummer Alan White.

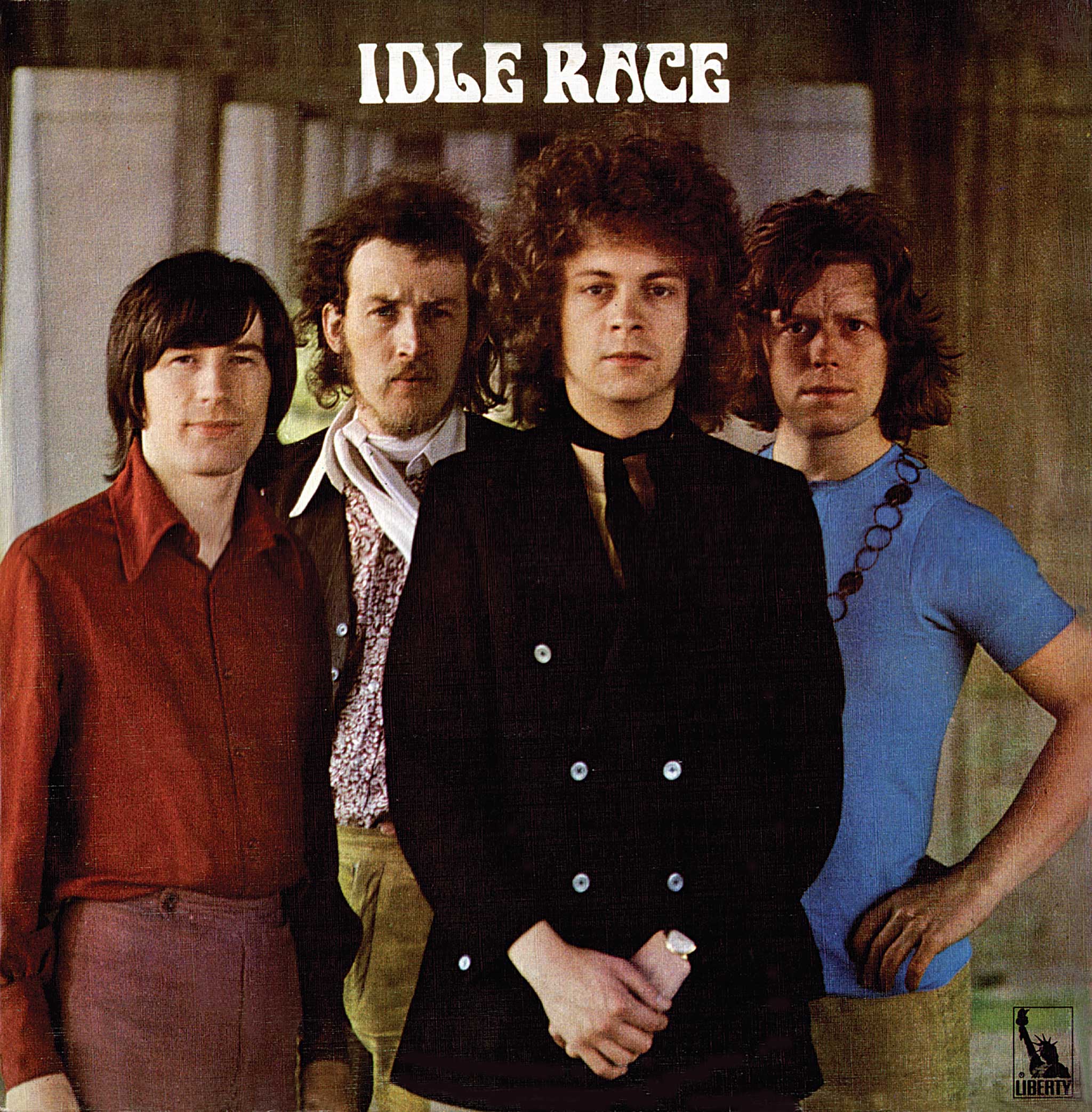

Meanwhile, Jeff Lynne had been struggling to make his own mark with The Idle Race. While playing in local groups, Lynne taught himself recording on his stereo tape machine and was already well-developed by 1966, when he joined the same Nightriders that Wood had ridden with. Chiming with the times, the Nightriders changed their name to The Idle Race in 1966.

Although winning critical acclaim (and praise from Beatles) with two albums of melodic paisley pop with Lynne’s heavy Beatles overtones, led by magical singles such as Skeleton And the Roundabout and The Birthday Party, The Idle Race just couldn’t hit the charts. Maybe Lynne’s songs were too idiosyncratic for those loved up times, notably singles such as Impostors Of Life’s Magazine.

“Yeah, it was all pretty wacky, that stuff,” he says now. “There was nothing straightforward or remotely like a love song or anything. It was always peculiar subjects. I just couldn’t get into doing those love songs in them days.”

He credits the unusual approach to growing up. “My dad was a big George Formby fan and I used to hear lots of that when I was a kid. He also loved classical, so it all got mixed together somehow: George Formby doing classical!”

Lynne qualifies that surreal thought by adding, “Well, I suppose pop-rock is what I do. I don’t think I was progressing towards anything really. I just wrote what I wrote. I suppose when you look at it as a body of work, it is something, but to me I was just doing one little bit after another.”

Still living in hope, Lynne declined Wood’s early 1969 offer to replace Burton (as did Hank Marvin of the Shadows). With friction increasing between the mainstream-leaning Carl Wayne and Wood’s long-held dream of a classical rock band, the Electric Light Orchestra was originally conceived as a parallel project to The Move. Wayne quit The Move to hit the cabaret circuit after 1970’s Shazam, whose Cherry Blossom Clinic Revisited displayed Wood’s new classical vision by amping up Bach and Tchaikovsky.

As Lynne recalls, he and Wood had often talked about a classical rock project, which started germinating when he finally accepted The Move post in late 1970. “Me and Roy used to talk about it when I was in The Idle Race and he was in The Move. We’d meet up down the pub or in a club in Birmingham, or he’d come over to my house or I’d go over to his house and we’d listen to the records we’d just done. We discussed having this group for a couple of years, and finally we did it when I joined The Move. He asked me before but I still wanted to give The Idle Race more time because I really liked the guys and I enjoyed being with them. But I thought, four years is pretty long and I’m going to be too late if I don’t do something now; try and get a hit, you know. It wasn’t really long at all now that I think about it, but it seemed urgent at the time; ‘Get a hit, quick!’”

Lynne became The Move’s second songwriter on December 1970’s Looking On album, which yielded a hit with Brontosaurus. Its Lynne compositions were What? and epic prog-presaging Open Up Said The World At The Door, which he still holds in special regard.

“It has that real close jazzy harmony, lots of thirteenths in the chords. That was just venturing into that kind of world. It wasn’t really what I intended to do forever. That was just one of the styles that I did. I do many different styles on those albums, really.”

Wood and Lynne, plus Bevan, were now primarily concerned with the ELO concept, securing a deal with Harvest but having to work on it concurrently while they honoured The Move’s existing contract with October 1971’s acclaimed Message From The Country. The album included Lynne singing more of his compositions, including The Words Of Aaron and lustrous ballad No Time, which he describes as “just a strange one, again. I was never aiming for singles or anything; it was always more about album tracks in those days.”

This was followed by December’s Electric Light Orchestra, the band declaring its mission to “pick up where The Beatles had left off” with cello‑dominated outings such as Lynne’s Queen Of The Hours and 10538 Overture. After The Move hit for the last time with early 1972’s California Man and also released the first version of Lynne’s Do Ya, the band completed their transformation into ELO.

While 10538 Overture became their first Top 10 hit in June and recording commenced on ELO 2, Wood left to form Wizzard (this writer witnessed their first indoor show at Aylesbury’s Friars club that September, a drunken quasi-classical brawl joined by defecting ELO cellist Hugh McDowell and keyboardist Bill Hunt).

Meanwhile, with Richard Tandy moved to synths and keyboards, Lynne proceeded to take ELO on its path to global success. While now fully realising the vision he’d talked of with his old mate Roy Wood, ELO also clinched the success he’d dreamed of in The Idle Race. Wood would now bring Phil Spector’s widescreen productions into the glam era and score hardy perennial seasonal standard I Wish It Could Be Christmas Every Day. All told, a double Brummie triumph.