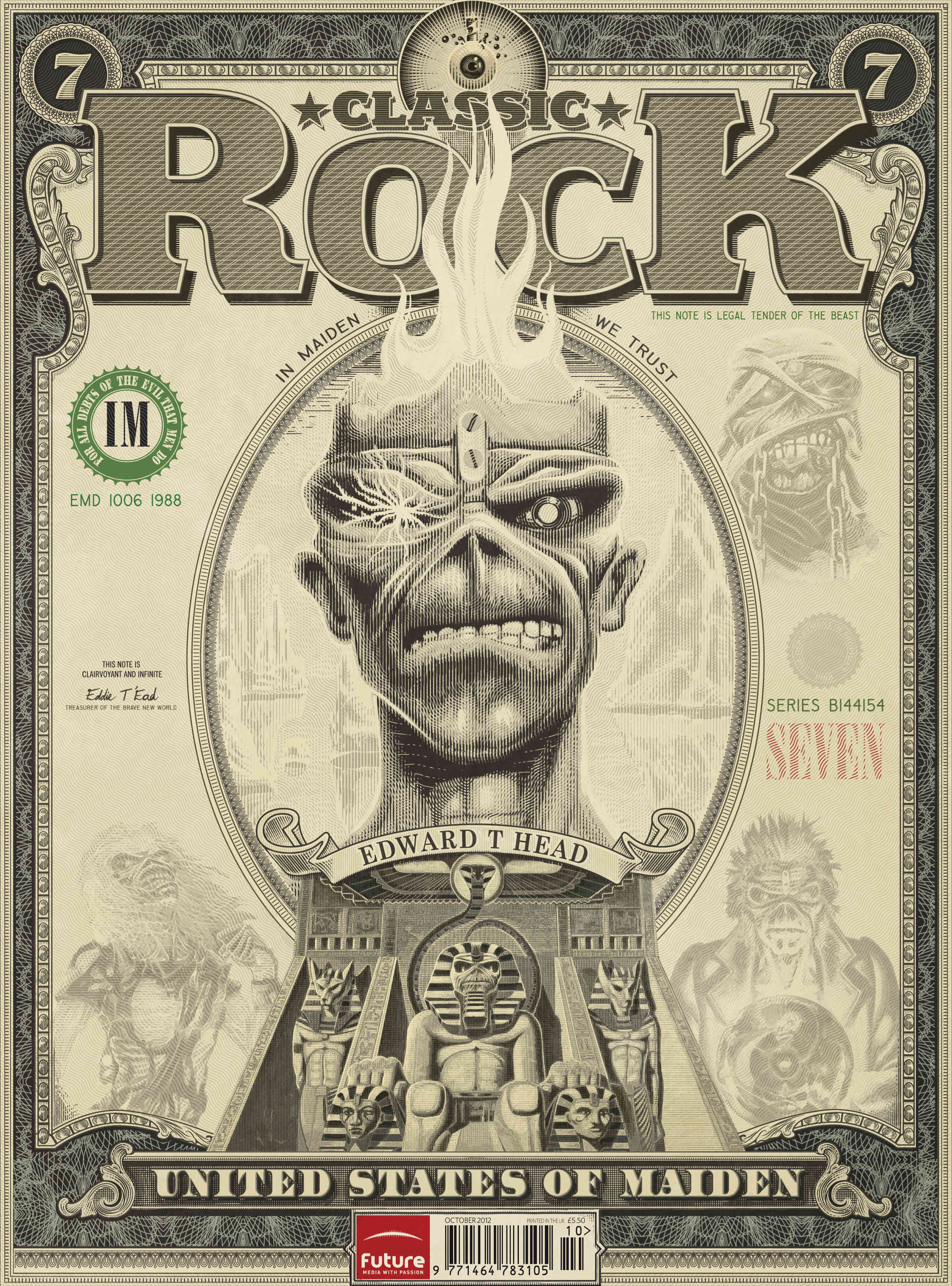

Iron Maiden were born in the East End of London, but their stellar 50-year career has seen them become one of the most globally popular metal bands of all time – not least in the USA and Canada. In 2012, as the band embarked on their Maiden England, Classic Rock joined them in Montreal to discover just how they conquered North America.

When the owners of the Aladdin Hotel decided to level the building with a series of controlled explosions in April 1998, not only did Las Vegas lose one of its most iconic structures, but the world lost a rock’n’roll landmark. It was here at the Aladdin that Elvis Presley married his 21-year-old fiancée Priscilla Beaulieu on May 1, 1967. The ensuing publicity established the newly opened hotel as one of Vegas’s premier nightspots, and in subsequent years the most storied names in the music business, from Frank Sinatra to Black Sabbath, would follow in The King’s shadow by taking headline bows in the hotel’s beautiful, 7,500 capacity theatre.

Surveying that room from the side of the stage on the evening of June 3, 1981, Iron Maiden’s 25-year-older leader Steve Harris was less concerned about the Aladdin’s rich heritage or its elegant architectural lines as by the sight of hundreds of stoned heshers slumped on the velvet-covered seats sweeping down to the lip of the stage. This was not quite the vibe Harris had envisaged for Maiden’s first gig on American soil.

As Maiden’s instrumental intro tape, Ides Of March, swelled out into the half-empty venue, Harris gestured to his bandmates to follow his lead and leapt over the stage monitors to confront the room, his face contorted with rage, his Fender Precision bass stabbing at the air, its headstock inches from the faces of startled crowd members.

“We were right in their faces, screaming: ‘Get up, you fucking wankers!’“ Harris recalls with a laugh. “People were sitting in their seats going, ‘Woah, what the hell is this?’ That was our first 10 seconds on stage in America. And we pretty much carried on from there with the same attitude.”

The story of Iron Maiden’s ascent to stardom in America in the 1980s is one of the great success stories of the decade. They weren’t the only British rock band to break through in the United States during the Reagen era, but, uniquely, their rise owed nothing to the patronage of the entertainment industry’s cultural gatekeepers or the endorsement of MTV, radio or the mainstream music press. This was a grass roots revolution driven by hard graft, business smarts, intractable self-belief and sheer bloody-mindedness.

In taking on America without anyone’s permission, the uncompromising working class East Londoners ultimately emerged victorious. But their triumph would come at a cost, jeopardising relationships both personal and professional, and threatening their own implosion.

Thirty years on from their Las Vegas debut, Maiden are back across the pond once more, for their most extensive North American campaign for more than a decade. The set-list and stage production for the 34-date Maiden England tour closely mirrors the 1989 concert video of the same name, shot at Birmingham’s NEC Arena during the tour in support of the previous year’s Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son album. As such it’s a history lesson for younger fans, and an opportunity to remind old-school fans of both the peerless quality of their back catalogue and their continued relevance.

Even by Maiden’s standards, the scale of the tour’s production is staggering – 22 vehicles are required to transport the band, crew, three animatronic Eddies, PA and pyro – and the gate receipts are equally impressive, with industry bible Billboard reporting gross ticket revenues of $500,000 to $850,000 per show.

Eleven dates into the tour, and Classic Rock finds ourselves at Montreal’s 11,700-capacity Bell Centre. As Steve Harris greets us with a firm handshake outside Maiden’s dressing room, it’s clear that the tour has already settled into a comfortable groove. Backstage the atmosphere is impressively serene, with production co-ordinator Zeb Minto and her assistant, Steve’s youngest daughter Kerry, ironing out potential problems for crew members and local stagehands with beatific calm.

The first band member to arrive at the venue this afternoon, Harris is in good form and good shape. Now resident in the US, he’s more attuned to the continent’s brutally humid summers, and daily tennis matches plus two-hour on-stage workouts have him looking tanned and lean. Unassuming and imperturbable, the 56-year-old bassist has always been wary of contributing to media spin and hype, making him a guarded interviewee. But this afternoon, as he retraces the path of his band’s ascent in the US, a smile spreads across his face as memories resurface.

“We were never obsessed with breaking America,” he insists. “We always planned to come out here and give everything we’d got, and they’d either like it or they wouldn’t. Fortunately for us they liked it. In fact they bloody loved it. But it was always a challenge. We didn’t do things the normal way. And maybe that’s why we’re still here.”

Unlike Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, or indeed NWOBHM peers Def Leppard (who made their own aspirations clear with the inclusion of a track titled Hello America on their debut album), Iron Maiden didn’t tour the US in support of their self-titled debut album. Their manager Rod Smallwood, however, did. A bluff Yorkshireman who’d entered the music industry as a booking agent, Smallwood had toured the US once before, when his act Cockney Rebel had supported The Kinks in 1975, but by his own admission he knew next to nothing about the US rock market. Concerned that his relative inexperience might hold Maiden’s career back, he considered calling in heavyweight US management to take charge of the band’s affairs Stateside, but was talked out of the idea by his friend and mentor Clive Calder, a South African record industry executive.

“When you talk about Maiden you’ve got passion in your eyes,” Calder noted. “Go see the American label and convince them.”

And so, in the autumn of 1980, while Maiden hitched a ride on Kiss’s European tour, Smallwood went “into battle” in the USA.

“My belief and Steve’s belief in the band was absolute,” he recalls now. “At that time there was no metal press, and all I ever heard in regards to American radio was: ‘They’re never going to play this…’ But the first album had done 60,000 copies on word-of-mouth, and I knew that if we got the US label on our side we had a great shot.”

Smallwood’s first point of contact at Maiden’s label, Capitol, was Bruce Ravid, a young A&R hotshot who’d brought The Knack and Duran Duran to the company and had struck up a friendship with Smallwood while working in the label’s promotions department in Cleveland in the mid-70s. Now an LA-based music industry consultant with two nationally syndicated radio shows, Ravid remembers Smallwood’s energy and passion for his charges electrifying the Capitol boardroom and instantly charming company President Don Zimmermann. Together, the three men set about formulating an unrelenting five-year plan for Maiden in the US, centred on a yearly release schedule, a brutal annual touring schedule, and ambitious merchandising and marketing campaigns aimed at making the band’s cadaverous sixth member, Eddie, an instantly identifiable icon in his own right.

With this blueprint in his back pocket, Smallwood hit the road on a charm offensive, visiting each one of Capitol’s 12 regional offices to sell the plan to the people who could actually make a difference for the band at a grass-roots level – the sales managers, promotion teams and customer service reps.

Today, Joel McFadden is a record label executive, but back then he was Capitol’s Minneapolis branch manager. He recalls Smallwood blowing into each city like a whirlwind.

“He was a force of nature,” he says. “He was very opinionated, very open-minded, and one of the most honest people I’ve known. He’d say: ‘I don’t know much about this market. Teach me.’ He knew where he wanted to go. And once you were part of his inner sanctum you felt like you’d do anything for him and the band. Long before Maiden set foot here, there were thousands of people who wanted to be part of breaking them in America.”

Iron Maiden finally touched down in America in support of their second album, Killers, in May 1981, following their first ever Japanese tour. With five days free before they were due to join Judas Priest’s World Wide Blitz tour in Las Vegas, half of the band, led by guitarist Dave Murray, decamped to Seattle to visit Jimi Hendrix’s grave, while Harris and Smallwood set up base in Los Angeles. On their first night in the city, Harris and guitarist Adrian Smith were taken to the Rainbow Bar & Grill, a notorious Hollywood club infamous as Led Zeppelin’s preferred Sunset Strip hangout throughout the 1970s.

By coincidence, Jimmy Page was holding court that night, and the Maiden party were invited to join him – a fact that didn’t go unnoticed by the club’s patrons. As word spread that there was a hot young English rock band in town, Maiden found themselves on the end of the sort of ‘hospitality’ they’d only ever dreamt about. Beers, weed and nubile young ladies were thrust in their direction from all sides. “There were chicks all over us,” Smith later recalled. “I didn’t even get time to finish me pizza!”

“It was unreal, just total overkill,” Steve Harris says with a laugh, while politely declining to go into detail about the extent of this debauched introduction to The Land Of The Free. “We were getting in all sorts of trouble. We were young and impressionable and things will happen. I thought: ‘Christ, I’ve got two months of this. I’m going to be dead at the end of it!’”

Maiden had supported Judas Priest in the UK the year before, although frontman Paul Di’Anno’s boast to Sounds magazine that Maiden would “blow the bollocks” off the headliners had done little to encourage a sense of bonhomie between the two bands. But Priest’s manager, Jim Dawson, was savvy enough to realise that the brash young Londoners would help draw a youthful audience to the US shows.

Maiden were given a 45-minute nightly slot, with minimal lightning and reduced PA. Expecting no favours, they grabbed the opportunity with both hands. They set off for the opening show at the Aladdin in two station wagons. Smallwood drove one, tour manager Tony Wigens the other, and their gear followed in a truck. Harris describes the trek as “a proper challenge”.

“We were up against it from day one,” he notes. “People had come to see Priest; we weren’t very well known over there at all. But we lapped it up. And right from the start we got incredible reactions. Just fantastic. And you start to think: ‘Maybe this could happen…’”

Maiden guitarist Dave Murray has equally vivid memories of that first tour. Then a baby-faced 26-year-old, he recalls being overwhelmed by a country where “everything seemed louder than everything else”. But he instinctively knew that there were opportunities in a land where the polished AOR of Foreigner and REO Speedwagon dominated rock radio airwaves as surely as Zeppelin and the Stones had a decade earlier. “We thought: ‘Hmm, this could be the beginning of something splendid,’” Murray says. “We were sleeping in the back of station wagons with pillows stolen from motels, but it didn’t matter. We would have hitch-hiked to the gigs if we had to, because those 45 minutes on stage were so incredible.”

The word-of-mouth buzz on the band grew as the tour progressed. A group of hard-core fans, billing themselves the Chicago Mutants, began following the band from city to city, their number swelling with each successive show. In Toronto 1,200 fans turned out for Maiden’s first Canadian headline date, on June 19; in New York 1,000 more swamped Brooklyn’s Zig Zag Records for an in-store signing session during a four-night stand at the Palladium.

“I was tired of Rush and Nugent and stuff like that,” one teenage metalhead told Canadian TV’s New Music Special during a 13-minute feature on Maiden. “And these guys offer something different.”

“We’re picking up fans all the way,” Paul Di’Anno proudly told the same interviewer. “Hopefully after another two years of touring we’ll be a huge name. But I hope everyone can say: ‘Oh yeah, Iron Maiden’s big now, but they ain’t changed a bit since we first seen them.’”

Ironically it was Di’Anno himself who had changed. The more technical nature of the Killers album left the singer feeling estranged from main songwriter Harris, and he began to question his own role within the band. Support sets left Maiden with a lot of free time to kill. And while his happy-go-lucky bandmates contented themselves with beer and “birds”, Di’Anno’s indulgences leant towards brandy and cocaine – a fact that didn’t go unnoticed as his on stage performances became increasingly lacklustre.

“We’d have a lot of time to hang around and get up to no good,” Harris recalls. “I was always the sensible one, trying to keep everyone together, but it’s difficult when you’ve got everyone wandering off in different directions with full glasses. But I’d always be thinking: ‘Let’s not lose focus on what we’re really here for.’ All our lives we’d all dreamt of being in a touring band, but when we got out there Paul wasn’t interested. I’m not into drugs myself, but I’m not against other people doing what they like – as long as it don’t fuck up their gig. Well, Paul was letting it fuck up his gig.”

When the tour wound up in Philadelphia on July 30, Maiden headed back to the West Coast for a brace of arena shows supporting UFO in California. Back at the Rainbow the following week, Harris confessed to Capitol Records’ Bruce Ravid that they were having issues with Di’Anno, and wondered aloud if replacing the singer would set back the progress Maiden had made over the previous two months. Ravid, who had noted a marked negativity in Di’Anno’s attitude towards US success even before the band touched down in the country, assured Harris that it wouldn’t, and that for all intents and purposes Eddie was the face of Iron Maiden in America. “If you’re going to make that change, now is the time to do it,” he advised.

Three weeks later, on August 29, Harris and Smallwood took a day out of Maiden’s European tour schedule to fly back to England to watch their NWOBHM peers Samson play the Reading festival. Backstage they extended an invitation to Samson vocalist Bruce Dickinson to try out for Maiden.

“When I get the job, which I will,” Dickinson cockily told the pair, “don’t expect that it’ll be the same as with the guy you’ve got at the moment.”

This was exactly what Harris and Smallwood wanted to hear.

In the evening of April 10, 1982 Iron Maiden’s third album, The Number Of The Beast, was unveiled as the UK’s new No.1 album. While champagne corks popped in EMI’s West London office, the band were in less celebratory mood, the news having reached them while they were pushing their broken-down tour bus along a snow-covered road in the Swiss Alps. The irony of the situation was not lost on Steve Harris, who understood that for Maiden the real work started now.

In America, the Beast campaign began modestly, with the album charting at No.150 in the same week Vangelis’s Chariots Of Fire soundtrack hit the No.1 spot. It was still hovering outside the Top 100 as the US leg of the Beast On The Road tour kicked off on May 11 at the Perani Arena & Event Center in Flint, Michigan. In consultation with Rod Smallwood, the band’s US booking agent, Bill Olsen, opted to bring Maiden back to the US as a support band once again, booking 13 shows on Rainbow’s Straight Between The Eyes tour, 20 gigs across the South-East with .38 Special, 41 dates with Scorpions and a further 30 shows on Judas Priest’s Screaming For Vengeance tour. Iron Maiden’s diary was filled to October.

From the outside, it may have appeared that Maiden were running to stand still – they were still travelling in station wagons, still restricted to 45-minute sets, still ignored by the mainstream media. But as the album inched up the US chart and tour receipts showed that the band were outselling the headline draws every night at the merchandise stand, Smallwood and Capitol could afford to be patient. Maiden had a growing presence on US college radio with the single Run To The Hills, and the band were being championed by the fanzine community which was spreading across the States. The buzz was growing.

Even beyond sales statistics and media attention, Capitol’s belief in Maiden was buoyed by the transformation in the band itself. Bringing in Bruce Dickinson was viewed by the label as “an immediate upgrade”, according to Bruce Ravid, and the increased confidence levels were apparent to all. Maiden finally had a vocalist capable of bringing drama and colour to their songs and, moreover, a frontman who could engage with an arena full of raging metalheads as if he were speaking to a close friend. For Dickinson, the experience was akin to “taking a very powerful drug every night”.

“Up to that point I’d only really been out of Britain on a couple of holidays and a school trip,” he told me two decades on from his inaugral US tour. “So a bunch of 24-year-olds from England let loose in America, pre-Aids, with endless supplies of drink and party material and an endless supply of willing young girls? Come on. We weren’t daft, but we weren’t vicars.”

The ’82 tour was not without controversy. The album’s title track and sleeve imagery led to accusations that Maiden were Devil-worshippers seeking to pervert the innocent youth of America. Copies of the album were set alight outside churches, gigs were picketed by incensed Christians, and right-wing pressure groups demanded the album be removed from record stores across the south. The label publicly made appropriately concerned noises, while privately welcoming the column inches. Meanwhile, the five carefree young Englishmen at the centre of the storm carried on regardless.

“It was mad,” Harris later said. “They got completely the wrong end of the stick. They obviously hadn’t read the lyrics. It’s no good getting upset about these fanatics. You can’t descend to their level.”

By the time Sounds magazine jetted out to Corpus Christi, Texas to cover the band’s burgeoning US success, the strength of Maiden’s connection with a new generation of suburban ‘earthdogs’ and ‘rivetheads’ was plain to see. As The Number Of The Beast hit No.33 on the Billboard chart, Sounds journalist Gary Bushell reported that Harris was being mobbed in the streets of one-horse Texan towns. Adrian Smith, meanwhile, recalled throwing open a hotel window one morning to find hundreds of kids in the car park below displaying Eddie’s skeletal face on tattoos, T-shirts and the hoods of their muscle cars. The cult was growing fast.

By the end of the North American leg of The Beast On The Road tour – 105 shows in total – the album had shifted 384,000 copies. According to Rod Smallwood’s blueprint it was time to move the Beast into arenas. While the band – now including new drummer Nicko McBrain – set to work upon their fourth album, Piece Of Mind, Smallwood sat down with Bob Olsen and a map of North America and began plotting a course from coast to coast for the summer and autumn of 1984: first the major cities (New York, Los Angeles, Dallas), then metal’s traditional blue-collar heartland (Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit), and finally the bridging towns (Peoria, Knoxville, Poughkeepsie, Madison). When they’d finished there were 80 marks on the map, taking Maiden deep into the heartland of the US on a scale few English rock bands had ever countenanced.

“In terms of statistics we weren’t really a headlining band,” Smallwood admits. “The sales weren’t significant enough for arenas, but being quite aggressive and excitable in those days we just went for it. We took Saxon and Fastway over and sold it as the British Metal Onslaught to make it a bit of a special package. If I’d known then what I know now I’d never have chanced it, but off we went. I remember the sales figures coming in for our Seattle date and we’d sold out – 11,000 people. A few weeks later we sold out Madison Square Garden for the first time, and we knew we’d pulled it off.”

The band were still on the road when Smallwood, now living in LA in a party pad above the Rainbow to get closer to the heart of the American record industry, began to plot their next moves. As he did so, news filtered through that Maiden had finally had a minor hit rising up the US rock radio charts. Ironically, that song was not the album’s designated singles Flight Of Icarus or The Trooper, but rather The Trooper’s B-side, a cover of Jethro Tull’s Cross-Eyed Mary. Sensing an opportunity, Capitol encouraged Smallwood to authorise a new pressing of Piece Of Mind, augmented by the Tull cover as a bonus track, and to push the band to schedule promotional radio station appearances. The manager flatly refused, unwilling to exploit Maiden’s loyal fan base. Capitol backed off, a decision which earned Smallwood’s respect.

“We weren’t into taking short cuts,” he muses today. “If we’d had one track hit big at radio we wouldn’t be where we are today. When you’re built up there you have further to fall. If the next album comes out and you don’t get airplay, you’re fucked. People gossip in this industry, and if you’re seen to lose momentum you’re in trouble. We needed to push on, on our own terms.”

Even today, at a time when dwindling record sales necessitate bands spending more and more time on the road in order to sustain a career, the statistics for Maiden’s World Slavery Tour make awesome reading. From August 9, 1984 through to July 5, 1985 they played 187 shows in 322 days across 24 countries. It would have been 192 shows had illness not forced them to cancel a week’s worth of US dates.

In its original form, mapped out to begin in Poland and end in Australia, the tour was daunting enough – Smallwood had booked the band four nights at London’s 5,000 capacity Hammersmith Odeon, four nights at the 13,000 capacity Long Beach Arena and a seven-night residency in New York’s Radio City Music Hall – but sheer momentum led to an additional two months’ worth of dates tacked on to the end of the run. The result was an epic undertaking which turned the band into genuine superstars – driving sales of parent album Powerslave to two million in the US alone – but also came perilously close to tearing the band apart.

Powerslave, released in September 1984, wasn’t necessarily Maiden’s finest album to this point, but it was undeniably their most ambitious. The centrepiece was Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, Harris’s 13-minute retelling of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic 18th-century poem, while the increasingly prolific Smith/Dickinson writing axis served up the album’s biggest hit single, 2 Minutes To Midnight. But the most important creative decision was to theme both Derek Riggs’s album artwork and the visuals for the subsequent tour around the Dickinson-penned title track, ostensibly a theatrical tale of Ancient Eygptian deities, masking a sobering reflection on the band’s own relentless drive for success. Brought to life by the Hertfordshire-based design company Brilliant Constructions, the hieroglyph-covered, sarcophagus-strewn stage set featured Eddie’s face rendered in the form of Sphinx, with the monster himself appearing as a 30-foot tall mummy with blazing eyes.

The tour itself was a sensation. Prefaced by Winston Churchill’s stirring war-time address to Parliament (“We shall fight on the beaches…”), the set clocked in at almost two hours, and was a masterclass in how to serve up a rock show. Dickinson was in particularly inspired form as the charismatic conductor of the band’s light and magic. Behind the scenes, though, the singer was slowly unravelling.

“It wasn’t just the length of the tour,” he later told me, “because I was pretty fit then, but also we were playing places where people didn’t seem to care about metal or Maiden. We were just another circus act going through town. I really hated that. By the end of the tour we were all taking the piss a bit: ‘If these people don’t care about what we do, why should we give a shit?’ At one gig I re-did the lyrics to 22 Acacia Avenue as a song about a cheese shop and no one even fucking cared. It was a daft thing to do, but I just thought: ‘What are we doing here if people don’t notice stuff like this?’ I knew that people would only entertain us for as long as we were the local freak show in town.”

Reflecting upon it all now, Steve Harris has sympathy for Dickinson.

“That tour fried everybody,” he says, “and him in particular. Christ, he had to get up and sing six nights a week for 13 months, and that took its toll. Our schedule then was insane. It wasn’t like anyone twisted our arms, we were totally up for it, but perhaps we took on more than we could deal with. I’m not saying it nearly broke the band, it didn’t. But we had to put our foot down and say to Rod: ‘Look, we need time off here or we’re in trouble.’”

“We should have stopped sooner,” Smallwood admits. “It was probably one of many mistakes I’ve made. But, you know, it was really hopping for us then and I was impatient. The jungle drums were summoning more and more people, and we wanted more. When we headlined the Piece Of Mind tour we were a new headliner and we didn’t really feel any pressure. But when you’re established as a headliner you have to deliver every night, and it’s a lot tougher mentally and hence physically. I just thought it was the same, but it’s not, it’s really not. It was too much.”

In the summer of 1985, as the exhausted band returned to the unfamiliar faces of family and friends in London, Rod Smallwood pondered Maiden’s next steps. The release of a double live album, Live After Death, with incendiary performances from Hammersmith Odeon and Long Beach Arena, would buy his boys a well-earned holiday. But where now and what next?

From his vantage point above the Sunset Strip, Smallwood was ideally placed to see that metal was changing. Clubs like the Rainbow, the Whisky A Go Go and Gazarri’s were being taken over by glammed-up pretty-boy musicians aping the sound and preening theatrics of local heroes Mötley Crüe, Ratt and W.A.S.P, the latter’s management Smallwood had taken over in 1983. A buzz was also building around the nascent thrash metal scene, headed by Metallica. When Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich visited Smallwood’s LA apartment early in 1986 with an unmixed cassette of his band’s third album, Master Of Puppets, Maiden’s manager instinctively understood that a cultural and generational divide was opening up within metal, offering a whole new set of challenges for his own band.

“Did I care?” he says. “Of course I fucking cared! I’m competitive in everything. You have to keep an eye on what’s going. The industry needs fresh bands coming through all the time, but we weren’t ready to step aside for anyone.”

Drawing up another ambitious five-year plan, Smallwood earmarked 1989 as Maiden’s first full year off the album/tour treadmill, not knowing that by then the band would be fractured and heading for freefall.

With the gift of hindsight, it’s easy to see the World Slavery Tour as a pivotal moment in the disintegration of Maiden’s classic line-up. When the five-piece regrouped to work upon their sixth studio album, Somewhere In Time, Bruce Dickinson was still suffering psychologically. Not unkindly, Steve Harris recalls his frontman being “away with the fairies” at the time, proffering song ideas that jarred with his own vision for the band’s future. When the album was released, in September ’86, the singer’s name absent from the songwriting credits. A decade on, Dickinson admitted to Maiden’s official biographer Mick Wall that he felt “squashed inside… like a fly being swatted”.

Initially the rejection seemed to spur the singer on to new creative heights. Maiden’s next album, Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, was an ambitious, prog-tinged concept piece about fate, prophecy and predestination that included four Dickinson co-writes and some of the band’s strongest and most sophisticated material to date. Speaking on the eve of its release, the rejuvenated vocalist likened Seventh Son to “a heavy metal Dark Side Of The Moon”.

“If The Number Of The Beast brought heavy metal properly into the 1980s, which I believe it did, then with Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son I think we’ve shown the way for heavy metal in the 1990s,” he confidently told one writer. Bold words indeed.

In the UK the album was a huge success, reaching No.1, spawning four Top 10 singles and paving the way for a headlining appearance at the Monsters Of Rock festival at Donington Park in front of a record 107,000 crowd. Across Europe the album scored Top 10 placings almost everywhere. But in America its release heralded a down-turn in their fortunes. The album charted at No.12, and would go on to sell 1.2 million copies, but this represented a drop-off from the two million sales racked up by its predecessor, Somewhere In Time, which debuted one spot higher on the Billboard 200.

“When people here heard the album, I’m not sure they quite got it. Not straight away, anyway,” Steve Harris says today, choosing his words carefully. “America was a bit cold to it, really.”

Rod Smallwood is equally diplomatic, withdrawing an initial assessment that the album was perhaps “too sophisticated” for Maiden’s US audience, before settling on the word “different”.

“It was Maiden moving more proggy,” he notes. “The reception was disappointing because it was probably the first time that we didn’t move on a step in America. It just didn’t catch fire.”

Following the more stripped-back, modernist feel of the Somewhere In Time tour, the Seventh Tour Of A Seventh Tour production was a return to the grandiose staging of Powerslave. Inspired, as ever, by Derek Riggs’s album artwork, the stage set featured icebergs, state-of-the-art visuals, and Eddie recast as a crystal ball-gazing clairvoyant. Fifty-seven North America shows were booked, with Maiden taking with them as support then-rising LA rockers Guns N’ Roses – a band whose idea of rock’n’roll had precious little in common with Maiden’s vision. It was a decision both acts would come to regret.

“Our audience didn’t like them,” Harris says bluntly. “We started out in Canada and our crowd reacted really bad to them. I thought it’d get better but it didn’t that much. Axl really had the hump with the crowd, and he used to get pissed off and it just rubbed people up the wrong way.”

“To us, the whole thing was ridiculous,” Slash wrote in his 2007 autobiography. “We hated their stage show on sight and had a hard time playing with that ice scene backdrop behind us every night. We were so out of place that it was a challenge. That band is a British institution, and we realised that… we were an American upstart band fucking with their very established system.”

“We said hello a couple of times but we never had much to do with them really,” shrugs Harris. “We had our own issues. We’d be out playing six songs off the album, but it seemed that people were more into hearing the jukebox favourites, wanting us to play a bit too safe. It was disappointing.”

On June 5, as the tour reached the Shoreline Amphitheatre outside San Francisco, Axl Rose refused to leave his hotel room and informed his bandmates he was too ill to perform. The following day, ahead of two sold-out shows at the 16,000 Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre, GN’R pulled out of the tour, citing problems with Axl’s throat. The fact that their debut album Appetite For Destruction was then headed for the Billboard Top 10 while Seventh Son slipped in the opposite direction was presumably a simple coincidence, and Rod Smallwood maintains that not one single ticket was returned to the venue box office following of GN’R’s sudden exit.

Maiden were a little too preoccupied with their own internal chemistry to really care. Guitarist Adrian Smith was becoming isolated from the band. The following year he would announce he was leaving, bringing an end to Maiden’s ‘classic’ line-up.

“We could sense Adrian drifting away,” admits Harris. “He’d been moaning about his sound and this, that and the other for a couple of tours and it wasn’t doing the morale of the band any good. We’d all come off and go: ‘That was a great gig’, and he’d be sitting in the corner moaning. He just didn’t seem like he wanted to be there, really. He was just off on one, and we just couldn’t reel him back in.”

“The truth is I was unhappy,” Smith later admitted. “There were a lot of long phone calls. It was all very emotional. But at the same time [when I quit] it felt like it was a weight off my shoulders.”

Bruce Dickinson watched his friend’s departure with sadness and a certain gnawing sense of recognition. Though the Seventh Son album represented a high-water mark in his own contribution to Maiden’s sound and aesthetic, Dickinson too was beginning to tire of the band’s relentless schedule, and was beginning to feel the pressures of “trying to conform to the established Maiden routine”. He began to immerse himself in extracurricular activities – fencing, flying, writing a novel (the farcical The Adventures Of Lord Iffy Boatrace), and even a solo album (which would emerge in 1990 as Tattooed Millionaire), but the sense that he was locked into an endless groove in his day job persisted. It would be five years before the singer followed Smith out of the band. And when he finally did so, in August 1993, he admitted bluntly: “I’ve been creatively sleepwalking for the last five years.” It would take the best part of a decade for the union to be re-established.

On stage stage at the Bell Centre, in time-honoured fashion Bruce Dickinson is exhorting a rapturous audience to make themselves heard. “Scream for me, Montreal!” he hollers. “Scream for me, Montreal!”

If North America didn’t quite ‘get’ Iron Maiden on the Seventh Tour Of A Seventh Tour, the same cannot be said for the 11,700 Maiden fans revisiting that set-list tonight. The band sound terrific this evening, as vital and energetic as at any point in the past three decades.

Before the show, as news drifts backstage that the following day’s show at the 16,000-capacity Molson Amphitheatre in Toronto is completely sold out, Steve Harris can afford a smile when asked about his band’s prospect of repeating their 80s success in America three decades on. Never one for nostalgia, the bassist is bullish in his assertion that there’s much more to come from his band, who he characterises as content but not complacent in 2012. But even at his most hard-headed, Maiden’s indefatigable leader will concede that the 80s marked a defining period in his band’s special relationship with America.

“It definitely wasn’t an overnight thing,” he laughs. “Looking back, maybe we made things harder for ourselves than it might have been, but we always did things our own way. And now we’re still here, and our crowds are still here, who’s to say that wasn’t the right way all along?”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 176, September 2012