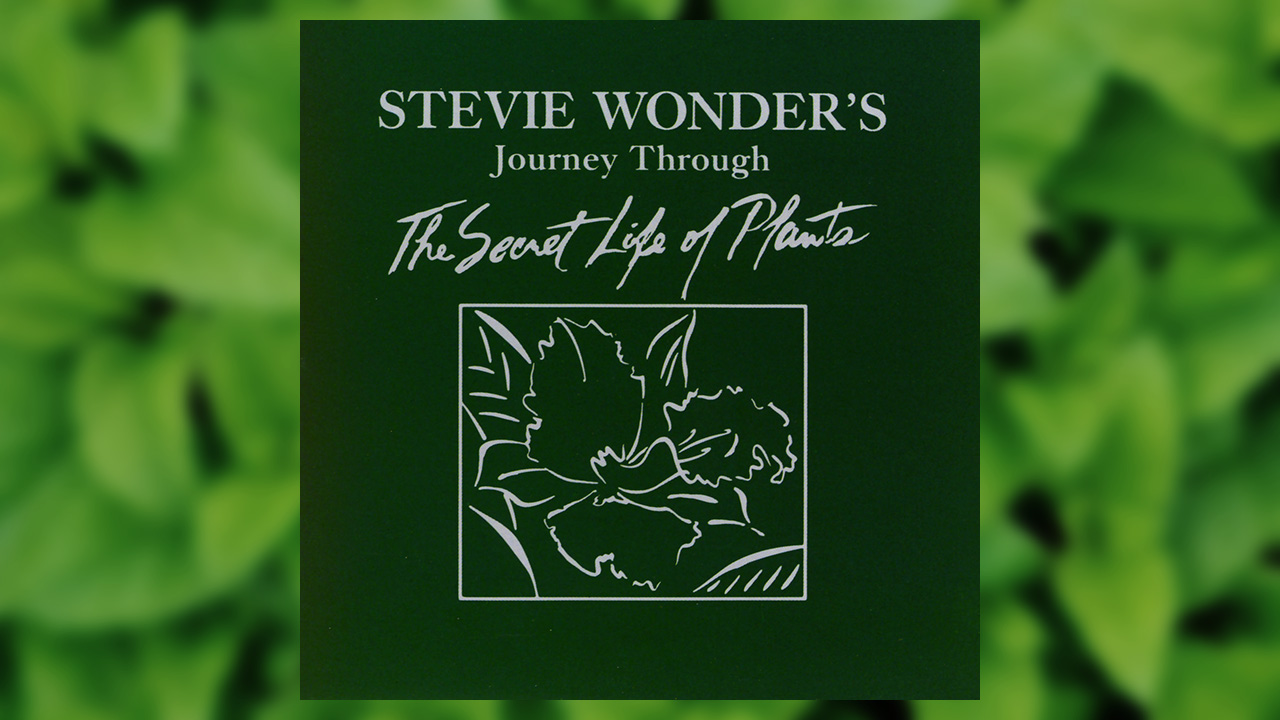

In 1979, everyone thought the soul maestro was totally off his rocker when Stevie Wonder released a double album with the odd title Journey Through The Secret Life Of Plants. It was far removed from his usual excursions into the sophisticated realms of commercially successful adult pop, and many thought it sounded the death knell for his near three-decade rule as a prince of soul music.

If you look at the facts, it’s hard to argue with that much-held belief. Wonder had been a chart force for so long and, in 1976, had put out one of his most acclaimed albums, Songs In The Key Of Life. When he finally issued what was assumed to be the follow-up three years later, it caught everyone off guard.

For starters, the album was actually the soundtrack to a nature documentary called The Secret Life Of Plants. The film was directed by Walon Green and based on Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird’s book of the same name, which explored controversial experiments proving plants are sentient.

More important was the way that Wonder fully immersed himself in the subject matter and captured both the spirit and ambience of the documentary, which used striking time-lapse photography. The whole structure and flow of the visuals demanded a left-field approach to the music, and that was something the multi-instrumentalist embraced with fervour and passionate commitment.

The result was a supremely experimental album, one rightly described later as Stevie Wonder’s Dark Side Of The Moon. It begins with the primordial yet controlled force of Earth’s Creation, and from then on in, becomes surreal and challenging.

Venus’ Flytrap And The Bug has an eerie robotic vocal, while elsewhere Wonder unfurls Japanese poetry recital, harrowing children’s cries and synth daubs, which were unusual for the time. He also dabbles in digital sampling, which was cutting edge back then.

Throughout, the music nods towards Krautrock, but is seemingly agitating and unsettling. Even when Wonder goes for a more obviously straightforward melody, such as on Come Back As A Flower, he does it with the type of progressive inclination that suggests there’s an undercurrent of thinking out of the box.

When it was released, the album got a negative reaction from those who were used to something more straightforward from Stevie Wonder; they failed to appreciate that what he was doing was enlightening, and had much in common with Tangerine Dream. The man himself rates this as one of his favourite albums. With good reason.