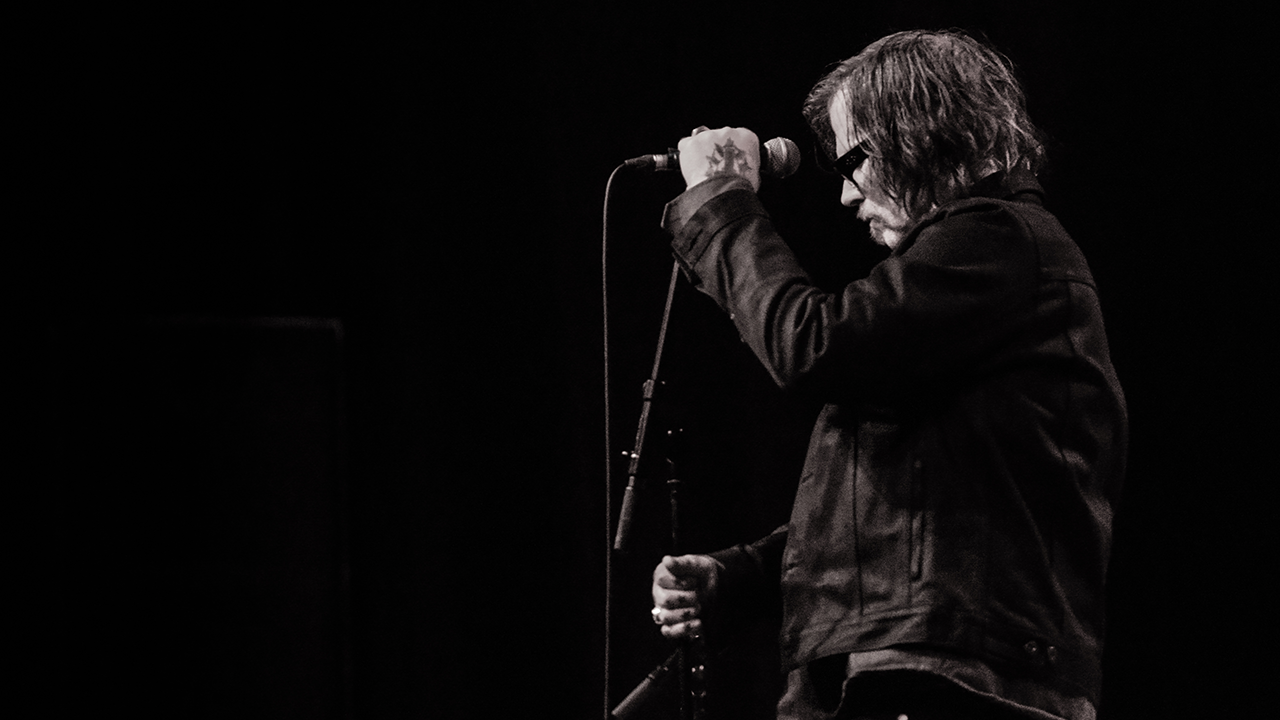

Mark Lanegan has made it into his mid-50s while mostly avoiding his past. Indeed, the last decade has been the most prolific of his long career, having released six albums and a dizzying stack of collaborations, with Queens Of The Stone Age, Neko Case, Duke Garwood, Earth, The Twilight Singers and many more. This year, however, he’s finally decided to confront a few ghosts.

He has simultaneously released the intensely autobiographical Straight Songs Of Sorrow, his twelfth solo album, and published his remarkably candid memoir Sing Backwards And Weep. “I didn’t really expect to find what was back there in my memory, because it was a time and place that I’d gone out of my way to forget,” he tells Classic Rock, sitting in his home in California. “It was an extremely dark and unhappy period to revisit.”

The book traces Lanegan’s story from juvenile delinquency in rural Washington state through to his time as lead singer in Seattle grunge-rockers Screaming Trees, a cantankerous bunch who became known for in-fighting, drugs and drunkenness as much as for their music. It’s all related in debauched, eye-popping detail. Lanegan writes of being addicted to heroin, booze and petty theft as a teenage redneck, spared from prison only by the good grace of the local judge. He’s so self-destructive that he expects to die at any given moment. His time in the Trees isn’t any happier.

Ultimately though, Sing Backwards And Weep is about salvation. And comradeship. Lanegan is still here to tell his tale, unlike some of the close friends who shared his journey into the 90s: Kurt Cobain, Jeffrey Lee Pierce and Alice In Chains singer Layne Staley. Their memories are pressed deep into the folds of the new album too, alongside other episodes and characters from Lanegan’s turbulent former life. As he wonders aloud in his sonorous drawl on Skeleton Key, a standout from Straight Songs Of Sorrow: ‘I spent my life trying every way to die/Is it my fate to be the last one standing?’

The songs on the album were written immediately after completing Sing Backwards And Weep, drawing from the same troubled well of experience. “I’d spend fourteen-hour days and realise that I hadn’t moved from the chair,” Lanegan says of writing the book. “If I was a character actor I would’ve been DeNiro in Raging Bull. I did everything short of taking up a needle and a pipe. There were a lot of memories to choose from. It covers a ten-year span and, frankly, shit was happening every single day. The kind of things that most people only go through maybe once in their entire life. So I had to be careful.”

So what brought all this on? Lanegan suggests that, to begin with at least, his hand was forced. He refers to “this prick” journalist who’s been pestering him for years to be interviewed for a book on the history of grunge.

“Up until now I would never talk about that time period, because I just wanted to keep making music,” he explains. “I didn’t want to get snagged with this huge ‘G’ on my forehead and always be thought of as the junkie grunge singer who never made it. That was the way I was painted many times afterwards. The fact that I’ve gone on to make some sort of career is a miracle in itself.

“Telling my story was something I had to think long and hard about, because my friends were such famous people,” he continues. “I had to include them because I spent all my time with them, but I didn’t want it to turn out like a National Enquirer kind of shitty, tell-all rock bio. I never felt any jealousy or used anybody’s success as a yardstick for my own. The success my friends enjoyed was so phenomenally huge that it was outside the realm, especially because we all came up in the same way: you meet some guys who like the same kind of music, you rehearse in somebody’s bedroom or garage, then, if you’re lucky, you make a record. And the Trees were lucky enough to make six terrible records.”

Lanegan is selling himself short here. Screaming Trees left behind more than their share of sterling music. Heavy psychedelia and garage-rock hooks turned 1992’s Sweet Oblivion album into a minor classic, the band briefly threatening a major breakthrough when Nearly Lost You appeared on the soundtrack of Cameron Crowe’s film Singles. The Trees’ swansong album, Dust, in 1996, was a thing of shadowy beauty, incorporating dark textures of gothic blues and folk that would become hallmarks of Lanegan’s solo output.

It’s no coincidence that Screaming Trees fully hit their stride only in the latter half of their career, just as Lanegan was stepping out on his own. The band’s aforementioned peaks rise on either side of 1994’s Whiskey For The Holy Ghost, Lanegan’s exquisite second album. It was a significant moment from a creative viewpoint.

“That record did wonders for me within the band,” he recalls. “The process made me want to force my way into exclusiveness in the songwriting process, which, until Sweet Oblivion, had almost totally belonged to [guitarist] Gary Lee Conner. Singing his songs was difficult for me because I had no emotional connection to them. All the time, I was looking for any excuse to do my own stuff.”

Formed in 1985 in his home town of Ellensburg, Screaming Trees provided a lifeline for Lanegan. His post-high school years were marked by alcoholic blackouts, bad relationships and a series of rotten jobs. He originally fell in with the Conner brothers – Gary Lee and bassist Van – when he was hired as a repo man for their father’s video store. After a debut LP on local label Velvetone, the Trees were picked up by SST Records.

“Signing to SST was a huge deal for us, because we were the first Washington state band to do that,” Lanegan remembers. “They were also by far the hippest indie label in the States at the time. I’ll never forget Greg Ginn [SST founder and Black Flag guitarist] saying: ‘Yeah, we have our own in-house booking agent for touring.’ And I was thinking: ‘What’s a booking agent?’ We’d only played maybe five shows, and those were in record stores and on tiny radio shows.”

If Screaming Trees served to offer Lanegan both a future and a way out of Ellensburg, it also brought him into contact with his peers. One early fan was Kurt Cobain, who pitched up in town with Nirvana in June 1988.

“My friend told me they were playing at Ellensburg Public Library and that I should go along,” Lanegan recalls. “We’d just lost [temporarily] Van and, because of the physicality of the Trees, I thought the replacement had to be somebody with a certain charisma and stature. I saw Nirvana warming up and was staring at Krist Novoselic, because I decided he was going to be my next bass player. Then immediately after they started playing I realised I was witnessing something really special. It was just obvious that these guys were built for something much bigger than I would ever be.

“Kurt came over in the parking lot afterwards, thanked me for coming and we exchanged phone numbers. I actually thanked him, because at the time I was in a pretty deep depression, and seeing them gave me a sense of excitement and something positive to think about. A few weeks later, Krist Novoselic called to see if the Trees still needed a bass player, but I told him that he was going to want to stay in Nirvana. Kurt always knew what he was doing. He wanted to achieve greatness. And not only did he achieve it, but also he stepped way over the line.”

As life in Screaming Trees became ever more unbearable, exaggerated by the constant feuding of the Conner bothers, Lanegan sank deeper into his addictions. He thought about quitting many times. The only problem was that he couldn’t face the alternative – moving back to Ellensburg.

The only redeeming factors were music and friends, a combination that often went hand in hand. He and Cobain would hang out in Olympia or back at Lanegan’s place, listening to records. “We were both huge fans of really old blues, especially Lead Belly,” he explains. “That was one of the things that drew us together.”

Sometime in 1989, the pair decided to record an album of Lead Belly covers. One of them was Where Did You Sleep Last Night, a version of which (with Cobain on guitar and backing vocals) fetched up a year later on Lanegan’s solo debut, The Winding Sheet. And while Nirvana would cover it themselves on MTV Unplugged, the Lead Belly album never quite happened.

“We recorded three songs in one day, but it turned out to be a pretty unproductive exercise,” Lanegan remembers. “Looking back, it was mainly because of the respect that Kurt and I had for each other. Nobody wanted to grab the reins because we were each so afraid of stepping on the other guy’s toes. It took me a really long time to realise that’s what happened.”

As for another great friend, Lanegan first bumped into Layne Staley outside a dope house in Seattle, when both of them were looking to score heroin. Despite his personal issues, Staley quickly became a dear companion and a role model of sorts.

“He was superintelligent, with this really strange, elevated humour,” Lanegan says. “He also saw the world in a much clearer way than I did, and was huge in terms of really helping me develop from this trailer-park trash into somebody who had some empathy for people. I learned a lot about love from him. Layne was a patient and necessary teacher for me.”

Witnessing Alice In Chains up close was also an epiphany: “Never have I stood by the side of a stage and seen somebody singing so hard that it felt like I was going to have a heart attack. Layne was a one-of-a-kind singer, with amazing power, and he and Jerry [Cantrell] were genius songwriters. For me, they were the most original band in Seattle.”

Sing Backwards And Weep ends with Lanegan receiving news of Staley’s death, from a drug overdose, in 2002. He’d been expecting it for years, but it was a devastating blow nonetheless. His loss is, he says, “a void I’ve felt every day since”. Lanegan had prematurely memorialised him in song on Last One In The World, on 1998’s Scraps At Midnight.

Staley’s death closes Lanegan’s memoir on a sombre note. Its author, however, was by then busy staying clean. In the late 90s, after years of depravity – culminating in a period where he forwent his music career and lived on the streets, funding his heroin habit by shoplifting – he’d entered a Californian rehab facility.

He was working for a demolition company in LA when Duff McKagan turned up at his door.

“I was in a halfway house somewhere nearby,” says Lanegan. “Duff came looking for me because I was a Seattle guy and he was a fan. He was in punk bands in Seattle before he went to live in the San Fernando Valley. ‘Friend’ isn’t a strong enough word to cover what he’s done for me.”

The Guns N’ Roses man took Lanegan in and employed him as a housesitter. Another local, Josh Homme, who’d once been the Trees’ temporary guitarist, got in touch around the same time. He told Lanegan he was starting up a new band, Queens Of The Stone Age, and asked if he fancied being part of it. Lanegan made his debut with the band on 2000’s Rated R, and remained with them until 2005. During that time he had also been invited into The Twilight Singers, conceived by Afghan Whigs’ Greg Dulli. The two of them would go on to record as The Gutter Twins.

Lanegan says he is eternally in debt to all of them.

“I was talking to my sister recently, and she said that I’ve been surrounded by angels my entire life,” he says. “Like Duff and Josh, Greg Dulli has also been there for me at times in my life where I’ve put myself into positions that a person shouldn’t rightly get out of. I’ve had these guys pick me up, and I owe all three of them – and a huge amount of other people as well – my continued existence on this planet.”

Lanegan may have arrived with grunge, but, unlike many of his peers, he’s not defined by it. He came of age later instead, creating a solo catalogue as deep as it is broad, shaped by a turbulent past that often threatened to engulf him completely. These true-life misadventures, wrapped in narcotic, faintly malevolent swirls of blues, folk, rock and electronica, are rendered all the more profound by one of the greatest singing voices of his generation. There’s a soulful, wounded quality to Lanegan’s delivery that brings emotional weight to everything he touches.

Straight Songs Of Sorrow is as good, if not better, than anything he’s ever put his name to. It’s an intensely personal, sometimes bleak collection of songs in which Lanegan processes self-loathing, pain, despair and visions of death in a way that’s ultimately hopeful and redemptive. At times it might not be the easiest listen, but it’s a thoroughly compelling one.

“Songs are always an expression of joy for me, no matter how sad they may seem to somebody else,” he reasons. “I don’t even call it work, because songwriting is more like a gift that I’m able to enjoy. A gift that somebody gave me, though I don’t know where or why.”

It’s difficult to equate the degenerate figure portrayed in Sing Backwards And Weep with today’s model. Lanegan is warm and engaging in conversation, and considers each question thoughtfully before answering in a soft, low burr. He laughs a lot, too, albeit a quiet chortle rather than a full belly roar.

He attributes his survival to being blessed with “a ton of luck, because I could very easily be dead or doing life in prison. But I had a lot of people who cared about me, and also a ton of stamina. The same thing that drove me in such a maniacal way towards drugs has actually been described to me as a survival gene. When I’m off drugs – and it’s been many years now since I quit – I still have the stamina to work for sixteen or eighteen hours a day, making music and touring as much as possible. My counsellor once told me that the word I should use is ‘passionate’, but I told him: ‘Passion is not enough to describe it.’ I have to be obsessed to get into the music I make.”

And what of the teenage Mark Lanegan? What would the lawless miscreant make of his sober, clean-living 55-year-old self?

“He’d be amazed he survived,” he says with a wry chuckle. “He’d think: ‘God, what kind of a pussy has he turned into? What’s up with you? I turn my back for a minute and you’re out of here!’”

Straight Songs Of Sorrow is out now via Heavenly Recordings.