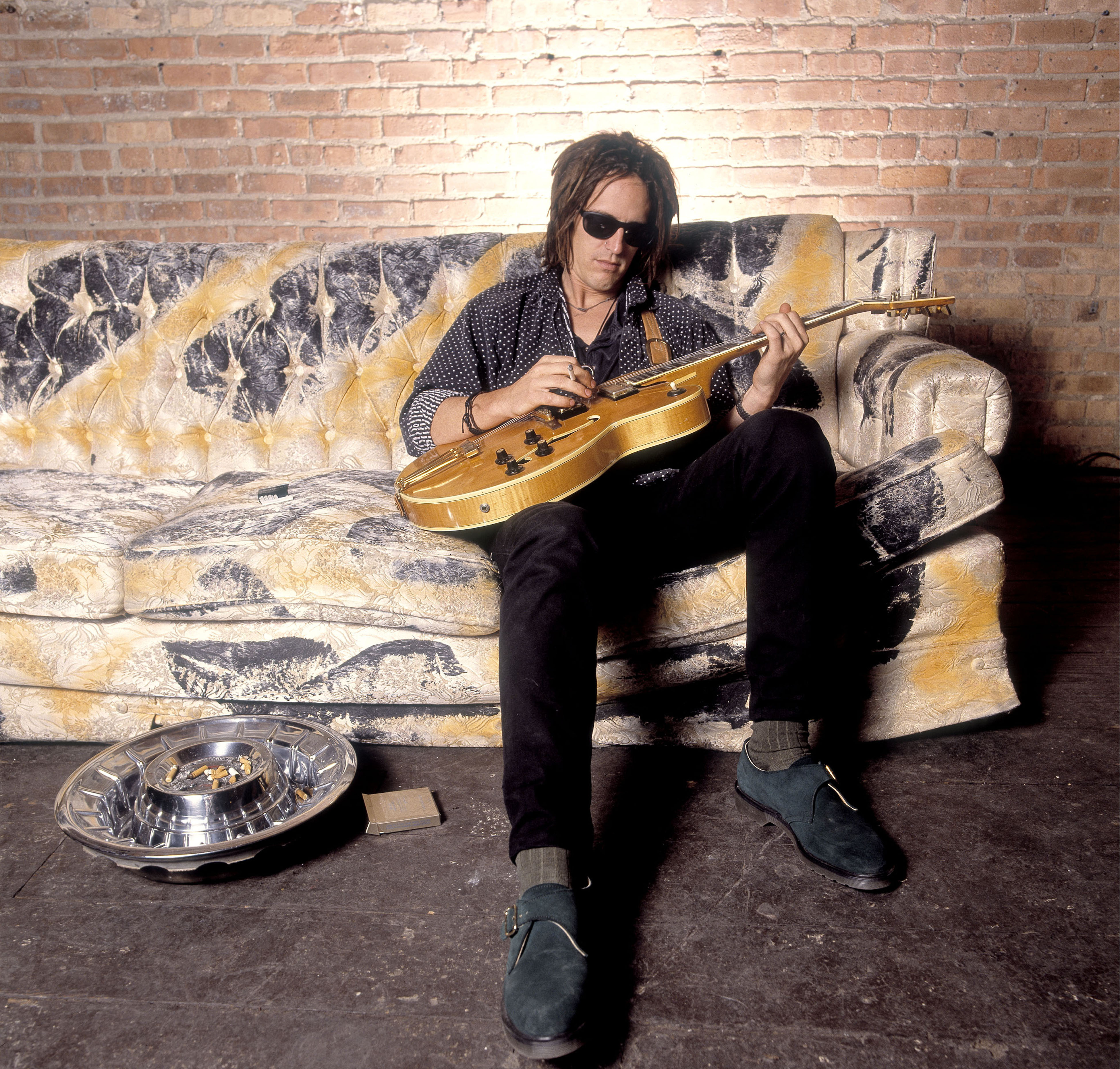

It’s been a long time since we last did this - 12 years, to be precise - but suddenly here he is, larger than life: Izzy Stradlin. Ex-Guns N’ Roses, ex-drug addict, but still, in his own way, as defiantly maverick as ever: sitting in a hotel room in London, looking tanned and healthy and sipping camomile tea. He has a plugged-in electric guitar balanced on his knees. Is he going to play us a song? Yes, he is. He picks it up and begins strumming. At first I don’t recognise it, then it hits me: Pretty Tied Up, one of his own from Use Your Illusion II. He starts singing: ‘I knew this chick… lived down on Melrose…’ Axl sang it on the album, of course. But that lazy Midwestern drawl belongs entirely to the guy who wrote it, the one with the low-slung ’tood and the cigarette dangling from his gob.

These days, of course, Axl isn’t around to sing it for Izzy. The cigarettes are gone, too: banished to the same dark place as the booze and drugs. He recently celebrated his 39th birthday and yet he looks younger, leaner, than he ever did back in the ba-ba-bad old days. Which throws the memory of our last meeting into even sharper relief. Back then, Izzy was wasted. But, hey, this was LA in 1989. and we all were. He had a cheque for $90,000 in his pocket, he said, but no bank account to put it in. “Give it to me,” I joked. “I’ll take care of it for you.” He staggered to his feet, appeared to actually consider the possibility for a moment, then folded it up and put it back in his pocket.

“Later, man,” he said. And now here we are. Much later…

Born Jeff Isabelle on April 8. 1962. Izzy, as he became known at school, is from Lafayette: the same Indiana backwater as his erstwhile partner in crime, Axl Rose – or just plain Bill Bailey, as he was back then. A small town with a courthouse, a college, a river, and some railroad tracks, Izzy recalls how: “We rode bikes, smoked pot, got into trouble – it was pretty Beavis And Butt-Head, actually.”

His grandmother played drums. She even had a band. “These old ladies who’d play swing and jazz at parties… [and] I’d watch The Partridge Family on TV and think, ‘That looks good, I’ll do that’.”

He first met Axl at Jefferson High school, in the mid-70s. “I remember, the first day at school there was this big fucking commotion. I heard all these books hit the ground, yelling, and then he went running past. A bunch of fucking teachers chasing him down the hallway…” The drummer in a school band, it was Izzy who persuaded the flame-haired youngster to have a go at singing. “I thought, well, here’s a guy who’s completely crazy, he’d be a fucking great singer. We had to coax him a bit [and] it didn’t go so well in the early days. Sometimes he would just come over and stand around, like he was embarrassed. Or he’d start to sing and then he’d just leave. Walk out and I wouldn’t see him again for like three days! “Some things don’t change, huh?” he adds with a rueful smile.

By the time Izzy left school at 17. (the only Gunner to actually receive a high school diploma) he was ready, he decided, for the big one: Los Angeles. His reasoning: “The weather was better and that’s where everything was.” Hitching down to Hollywood, he first became the drummer in punk band Naughty Women, then The Atoms. But when part of his drum kit was stolen, he sold the rest of it, bought a bass and joined Shire. Then changed his mind and left again to become a guitarist instead. Being the guitarist “seemed cooler” than being drummer and, most crucially, it was “easier to write songs on.” It was 198. and Izzy was living in a small apartment in Huntington Beach, an LA suburb, where he was occasionally joined by his old Indy pal, Axl. “He came out like three times before he stayed. Then, probably at the end of ’82. he came back out with this girl and rented an apartment, and that’s when he finally stayed.” Forming a band together “just seemed the obvious thing to do.”

As we now know, a combination of coincidences and chance fuck-ups (details of which still depend on who’s telling the story) then resulted in what became, in June 1985. the first permanent line-up of Guns N’ Roses: Axl on vocals, Slash on lead guitar, Izzy on rhythm, displaced Seattle punk Michael ‘Duff’ McKagan on bass and Slash’s old school pal Steven Adler on drums. What happened next is now the stuff of legend. The crackling, diamond-hard, expletive-sprayed monster that was Appetite For Destruction, their first album sold more than 4 million copies and wrote the band its own asterisk-heavy chapter in the rock’n’roll history book. At a time when rock had sold its balls to the butchers – when Bon Jovi and Def Leppard were still considered ‘heavy’ – Guns N’ Roses came along and showed us how it should be done, putting booze and drugs back on the menu at a time when rock’s glitterati were still babbling on inanely about gyms and mineral water. This was rock without the condom on and soon almost everybody was infected.

“Man, once that shit started happening, it was like, forget it. Just hang on,” Izzy says now with a slow, still incredulous shake of the head. “The rest was just a ride…” The fact that it was another three years before they would pull themselves together long enough to make a follow-up – the double Use Your Illusion I & II sets – only added to the mystique. In reality, however, the period was a desperately dark time for Guns N’ Roses. Not least Izzy, who found himself in the grip of heroin addiction. “Oh, yeah. But I was addicted to everything,” he says nonchalantly. “Whatever was going on. I didn’t even know I was in trouble until someone pointed it out to me…”

That someone happened to be Aerosmith singer Steven Tyler, whose own exploits in the field of ‘advanced chemistry’ were, at that point, better known even than Izzy’s. They had met when GN’R opened for the Aerosmith on a US tour in the Autumn of 1988. and had stayed in contact ever since. “I remember, we were talking on the phone and I said, ’Steven, I’ve got this hole that goes through the middle of my sinuses. I’ve got like one nostril now’. He goes, ‘Oh, yeah - deviated septum’. He knew all the terminology. I was like, what? Let me write this down. Oh, fuck, yeah! That’s me - wait, hang on…” Pretends to snort another line.

Izzy had been on the road with the band for over a year between the release of Appetite… and the end of the Aerosmith tour. After months of sharing the road with the likes of Mötley Crüe, Faster Pussycat, The Cult, Iron Maiden… The only way he knew how to handle it was to “make sure I was out of my skull for pretty much all of it. We all did…” Doing drugs was “just normal, something we’d all been into since we were kids. Then we toured with Aerosmith and it was like, thank God we got to meet some people that weren’t fucked up! It influenced me big time. Tyler and those guys, they were always like my rock idols. Growing up in Indiana, I loved fucking Aerosmith, man. Smoke a joint, listen to the first record… “When we toured with them I’d go out to watch and they’d sound fucking amazing! I thought, we’re gonna have to really pull this shit together to keep up. Cos they were tight, you know? And with us, even then, it was like the music was taking a back seat to all the other shit…”

By the start of 1989. Izzy and the band were off the road at last but now a new reality began to dawn. “We’d stopped hanging out together – me, Duff, Slash, all of us. Isolated in small apartments somewhere. The drugs and drinking and stuff was a big part of the isolation. It was like self-imposed and it became worse. The drugs and all that just got worse…” Through it all, however, he kept up a dialogue with Steven Tyler. “I had a lot of conversations with Steven. Mainly, he would tell me really fucking scary drug stories - shit like locking himself in a bathroom and filling in all the tile cracks with toothpaste. And seeing worms… I thought, ‘Whoah, I’ll never get that bad!’ “Then another half-a-year went by and I found myself driving down the 101 freeway in LA and I’m seeing snow, cos I’ve been up for like days, doing coke. Oh, man… And then that fuckin’ worm thing came up!

- Stop being mean to Axl! Here's six really nice memes to redress the balance

- Opinion: Why Izzy Stradlin was the heart of Guns N' Roses

- Izzy Stradlin explains Guns N’ Roses absence

- Slash: My Life Story

“I was staying with this coke dealer, I’d been up for five fucking days, and I was out in his garage, for what reason I’ll never know. And I pulled open this drawer of nuts and screws, and sure enough, man, they were turning into maggots! I thought, I gotta get the fuck out of here…” But if Tyler had been influential in getting Izzy to at least think about getting straight, it was one, now infamous incident, that really forced the issue: when he was arrested on a domestic US flight from LA to Phoenix for urinating in the aisle of the First Class section. “Ah, I was drunk, man. Then waking up in jail… Not cool, man,” he says with an embarrassed grin. Because it happened in ‘federal airspace’, the US authorities were rather less amused. Taking into consideration a prior arrest for marijuana possession, Izzy was put on probation for a year and – irony of ironies – subjected to random urine tests. Now he really had to stop: the law demanded it. “Suddenly, I can’t use drugs anymore or I’m going to jail. Wow…” Suddenly the band’s enforced lay-off had an unforeseen positive side. With the time and the motive to clean up his act properly, Izzy went into rehab and began receiving professional counselling. What really made him stop, though, he thinks now, “was I wanted to. Cos I figured, at some point your heart’s just gonna pop, or your mind’s gonna snap, right? Eventually, that shit will kill ya, and it does. It kills people all the time. Once I got maybe like a week of sobriety, like actually going a whole week without a drink, I thought, oh god, if I can just keep this up…”

The biggest test for the newly sober guitarist was returning to the band. “I’d come in for rehearsals for Use Your Illusion and there’s one of the guys with a big line of coke. ‘Hey, Iz - you want some coke?’ ‘Ah, no thanks, I just got back from my probation officer, you know?’ To get sober is really [tough] but to do it like that, in a situation where everybody’s still using…” Nevertheless, he persisted for almost a year. Recording wasn’t so bad - remarkably, basic tracks for both Use Your Illusion albums took less than two weeks, he says. It was going back out on the road that did for him in the end. “The shows were completely erratic. I never knew whether we’d be able to finish the show from day-to-day, cos [Axl] would walk off…”

They say that in the country of the blind the one-eyed man is king, but for Izzy, returning to the road with Guns N’ Roses, in 1991. was “a nightmare.” Axl’s ‘mood swings’ had become so regular, “I said to Duff and Slash, we gotta learn a cover song or something, for when [Axl] leaves the stage. They were like, ‘Ah, let’s have another beer…’ They didn’t care.” The lowest point was the notorious riot that ensued halfway through a show in St. Louis in 1991. after Axl first dived into the crowd and then refused to continue the show because someone in the audience had taken a picture. Possibly the most unsavoury incident in the band’s crazed, incident-driven career, as Izzy says now: “When something like that happens, you can’t help but think back to Donington [in 1988. when two fans were trampled to death in the rush for the stage at the start of GN’R’s set]. What’s to stop us from having some more people trampled - because the singer doesn’t like something? Like, what’s the point? What are we getting at here?”

Travelling in his own trailer-truck from gig to gig while the others flew - no longer able merely to lose himself in the illusion - Izzy knew it was only a matter of time before he bailed out completely. Steven had already gone - hypocritically bumped out of the band for failing to deal with his own drug problems. Things just weren’t the same anymore. “The music had taken a back seat completely, there was nothing new coming from us. We didn’t sit around and play acoustic guitars anymore. It was like, oh, time to go on - where’s the singer? The singer walked off? Now what do we do?” “We’d started out as a garage band and it became like a huge band, which was fine. But everything was so magnified… Drug addictions, personalities, just the craziness that was already there anyway. The nuttiness. It just became… too much. Plus, my friends, these guys… I’m basically watching them kill themselves. Not so much Axl, but Slash and Duff – these guys were on my top ten list of guys that might die this week. And I’m thinking, ‘You know what? I just don’t want to be part of it. It didn’t feel like it was good.”

Izzy’s decision to leave Guns N’ Roses was announced officially in November 1991. Looking back at the cuttings, it seems like nobody made much fuss about it. The downsizing of GN’R to the Axl & Slash Show had begun long before that.

Unlike Steven Adler, whose career nose-dived after leaving the band, Izzy’s first impulse was to start up his own band - the Ju Ju Hounds. An album of the same name quickly followed and within a year Izzy was back on tour, only this time it was clubs and theatres (including a warmly-received appearance at London’s Town & Country club). “No more hockey stadiums,” he shudders. A more low-key recording than the inflamed GN’R catalogue he had helped produce, Ju Ju Hounds perfectly mirrored its creator’s new outlook: funky, free-flowing, unworried. Not a bit like the band – or the man – he left behind. “When I got out of Guns N’ Roses, I started riding bikes again. Cos I rode ’em as a kid. And then I stopped for a few years in LA cos I didn’t have a bike.” Which was probably just as well, giving his, uh, state of mind then. “Fucking A!” he laughs. “Damn straight, or I probably wouldn’t be sitting here now. But I did a lot of things I hadn’t done for a long time. I just started…” His hands fiddle with the guitar again as he searches for the right words. “I just started living again…”

Musically, at first he found it hard not having the rest of the band to bounce off of. “In Guns N’ Roses I’d write a bunch of songs and I’d play them for Axl and he’d go ‘Oh, that sounds like Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak. Or ‘That sounds like Queen!’ He would always pick this shit apart and sometimes it was annoying. But suddenly I’m in this new thing and I don’t have somebody [like that].” On the plus side, unlike Slash, who would eventually have to find a new frontman for his songs, singing was not a problem for Izzy. “It felt pretty natural. Axl was never usually there for rehearsals, so I’d be the guy singing a fucked-up version of Paradise City or whatever. It just became a matter of, ‘Well, now I always have to sing them’.” Had he been tempted to get a frontman, though? He nearly chokes on his chamomile. “No. By that point, I said I’d rather sit around and play acoustic guitar in my bedroom than try that.”

Nevertheless, Izzy did return briefly to the Gunners, in 1993. after Gilby Clarke, his short-lived replacement, busted his hand in a dirt bike accident. For the fans, it was a welcome return for one of the original members. For Izzy, “it was weird. We toured Greece, Istanbul, London – I liked that side of it, seeing some places I’d never seen.” But that was the only thing he did like about it. After he’d left the band, he had “a big shit load of money sitting somewhere [for me] and they weren’t paying me [it]. I don’t know the deal was, some kind of legal bullshit.” Funds, he claims, which were only released after he agreed to come back temporarily. “Money was a big sore point. I did the dates just for salary. I mean, I helped start this band…” Up comes the guitar again. A flurry of angry notes ensue. These were his final shows with Guns N’ Roses. He left without saying goodbye. “I didn’t actually say ‘see you’ cos they were all fucked up. Duff and these guys, they didn’t even recognise me. It was really bizarre. It was like playing with zombies. Ah, man, it was just horrible. Nobody was laughing anymore…”

He says his last face-to-face contact with Axl was six years ago. “I’d moved back out to LA. I bought this old Norton Commando 850. and was riding around one day and I thought, ‘Fuck it, I’ll go by his house. Bastard, he lives up in the hills, he’s got a big house, I’ll go and see what he’s doing’, you know? “And I go up and he’s got security gates, cameras, walls, all this shit, you know. So I’m ringing the buzzer, and eventually somebody comes and takes me up and there he is. He’s like, ‘Hey, man! Glad to see you!’ Gives me a big hug and shows me round his house. It was great. “Then, I don’t know, probably a month later, one night he calls me [and] we got into the issue of me leaving Guns N’ Roses. I told him how it was on my side. Told him exactly how I felt about it and why I left. And man, that’s the last time I’ve talked to the guy! “But, I mean, he had a fucking notepad. I could hear him [turning the pages] going, ‘Well, ah, you said in 1982. blah blah blah…’ And I’m like, what the fuck - 1982. He was bringing up a lot of really weird old shit. I’m like, ‘Whatever, man’. But that’s the last time I talked to him.

“Every two or three years I’ll put a call in to the office and say, ‘Hey, tell Axl gimme a call if he wants to’. But I mean… the weirdness of his life. To me, I live pretty normal. I can go anywhere. In 2001. I don’t think people really give a shit. But for Axl, I know for the longest time, because his face was all over the television and stuff, I don’t think he could really go anywhere or do anything. “And I think because of that he kind of put himself in a little hole up there in the hills. He kind of dug in deeper and deeper and now I think he’s gone so fucking deep he’s just… I mean, I could be completely wrong. But I know he doesn’t drive [unheard of in LA] and he doesn’t… He doesn’t do anything. I’ve never, never seen him in town. Isolation can be a bad thing, but Axl’s been at it for a long time now. You know, he always stays up at night…” He drifts off, not even trying to find the words this time.

The key to Axl’s personality, reckons Izzy, still lies back in Lafayette. “In high school, you know, Axl, he had long, red hair, he was a little guy and he got a lot of shit [because of it]. I think he never got laid, too, in school. I hate to bring this up cos this is getting nasty,” he laughs. “But he never got no pussy at school, Axl. So now the guy’s a big fucking rock star, he’s got the chicks lined up, he’s got money and he’s got people… and the power went to this guy’s head. I mean, he was a fucking monster! Nuts! Crazy!

“And I never saw it coming. I mean, this is my side of it, he’d probably say I’m completely fucking crazy, but I think he went power mad. Suddenly he was trying to control everything. Did you ever see those fucked up contracts for the journalists to sign?” he asks, referring to the notorious ‘consent forms’ that Axl foolishly tried to foist on the media in 1991. “The control issues just became worse and worse and eventually it filtered down to the band. He was trying to draw up contracts for everybody! And this guy, he’s not a Harvard graduate, Axl. He’s just a guy, just a little guy, who sings, is talented. But man, he turned into this fucking maniac. And I did, too, but it was a different kind of maniac. I was paranoid about the business aspect – freaking out going ‘Where’s all the money?’”

He tells a hair-raising story of a “missing” million-dollar advance from a merchandising company. “I’m out of my fucking gourd, right? I’m at the fax machine and I’ve got like a hundred faxes strung across this room. And I’ve got a pistol on the desk cos I kept hearing people walking on my roof, right?. So I’m snorting coke, faxes keep coming, snorting more coke… And I’m reading through this stuff, trying to just grasp what had happened to us. “The call that really sent me off my rocker was [from] one of the attorneys. I said, ‘There was a million-dollar advance, where is it?’ And he goes, ‘Well, Izzy, I don’t really know right now’. I was just like ‘Aaarrrgggghhhhhh!!’ It was just the last thing and I snapped completely.

“For [Axl] the money wasn’t as big a deal. But he had this power thing where he wanted complete control. And you can say, well, it goes back to your fucked up childhood where his dad used to smack him around, you know, and he had no control, so now he’s getting it back. But it’s like, it’s still cooky, you know? You don’t have to have everybody signing stuff.”

When Axl finally sent his old school friend a contract to sign, it was the final straw. “This is right before I left - demoting me to some lower position. They were gonna cut my percentage of royalties down. I was like ‘Fuck you! I’ve been there from day one, why should I do that? Fuck you, I’ll go play the Whiskey’. That’s what happened. It was insane.”

Axl still has his contracts, and still owns the band’s name. But in achieving these hard-fought goals he has sacrificed the one thing worth fighting for: the band themselves. That’s a strange way to conduct business. “I recognise it as something that’s not normal,” Izzy agrees. “Maybe it was just the stress and pressure of being him. I mean, he had people threatening to kill him constantly. So that’s got to be hard to deal with. Then you’ve got these fucking morons in the KKK thinking we’re behind them because of one song [One In A Million].” The decision to put One In Million on GN’R Lies, their 1989 mini-album - with its denigrating lines about ‘Immigrants and faggots’ coming to ‘our country’ to ‘spread some fuckin’ disease’ – was typical of the skewed thinking that now pilots the GN’R flagship alone. “That’s a song that the whole band says: ‘Don’t put that on there. You’re white, you’ve got red hair, don’t use it’. You know? ‘Fuck you! I’m gonna do it cos I’m Axl!’ OK, go ahead, it’s your fucking head. Of course, you’re guilty by association. [But] what are you gonna do? He’s out of control and I’m just the fucking guitar player…”

Interestingly, when I remark that it must feel like strange timing, to be here promoting his own album just as Axl is powering up for the next GN’R opus, he disagrees. “No, it’s perfect timing.” How so? Has he heard it? “Not a note. I’d like to hear it, actually.” How does he feel though knowing it’s being sold as a GN’R album? “Well, it’s obviously not Guns N’ Roses, I think all the fans [know that]. It’s not even right that he uses the name, because he’s the only guy [left]. I think ultimately it’s gonna work against him, because people are gonna say ‘Fuck you, wanker’ – that’s what they’ll call him here, right?. ‘You fucking wanker, that’s not Guns N’ Roses!’ Hopefully, the music’s good, cos if the music isn’t good then he’s gonna get the double-whammy…”

A hypothetical question then: Axl’s [solo] album flops, and he offers you all the chance to get back together - just like Aerosmith and Black Sabbath - would you do it? I mean, assuming Axl would be… “… broke?” he cuts in with a laugh. “I could hear the call.” Goes into gruff Axl impersonation: “‘You know, I’ve been, ah, thinking’. He talks really slow when he gets an idea like that. ‘Aahhh, I’ve been thinking…’ And I’d be thinking, ‘He must be broke’,” he chuckles. “That’s how I imagine the call.”

He says the band still get hopeful promoters trying to tempt them back together with promises of enormous wedge. “Oh, yeah. Around the big millennium hype, for sure.” Is he ever tempted? “Yeah, why not?” he chuckles. “A [one-off] gig would be easy, I would think.” What about an album, though? Now he really does laugh. “Well, you know what? It’s funny, cos like me, Duff and Slash - we could go in and make a Guns N’ Roses record in a week. Basic tracks. [But] vocals and leads [instrumentation] could take God knows how long…”

After the Ju Ju Hounds world tour in 1993. Izzy and his Swedish wife Aneka took to travelling… England, Trinidad, Costa Rica, Spain, Denmark and Sweden. They eventually settled back in Indiana in 1994. where they continue to partially reside, in between extended visits to LA whenever Izzy’s working. Although River will be his fourth solo album, the chief features of his post-GN’R career have been the extended bouts of motorbike riding and “just hanging out” he now spends most of his time doing. He says he’s happy sacrificing superstardom for doing his own thing. “I just wanna make cool records. I couldn’t give a shit about [stardom] at this point. I’m having a great time and there’s a lot of satisfaction in making it all fit together.”

Though generally good value, his albums usually receive only mixed reactions from the critics. The main stumbling block the very thing that gives them their strength: that they don’t sound remotely like Guns N’ Roses albums. “I was in that band so I know it’s what everyone wants to talk about,” he says. “But when I first did press, it was like, ‘I didn’t hear your record but I heard you did heroin’. I’m like, yeah, I did heroin. Next guy, ‘I didn’t hear your record but I heard you did heroin’. It was The Jerry Springer Show. At which point, I said, you know what, I’m done. Let’s take a break…” When he plays live now, he shies away from playing Guns N’ Roses songs.

“In the 80s, the band just struck a nerve. Uncanny. But since I left, I’ve never played any Guns N’ Roses songs. I played in Japan one time with Duff and we tried Paradise City but we couldn’t keep a straight face.” What if Axl turned up and wanted to sing something? “If Axl was in town and wanted to do Paradise City, we’d say ‘Fuck, yeah!’ We’ll play it if he’ll come up and sing it.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #28.