“Had my mother not had me adopted, would I have ended up in King Crimson?” Jakko Jakszyk discusses his abandoned football and acting ambitions, and the status of Robert Fripp’s band

The amateur impressionist on finding his birth mother then closing communications with her, Stiff Records’ plans to make him a star, and saying the “stupidest thing” to Michael Jackson

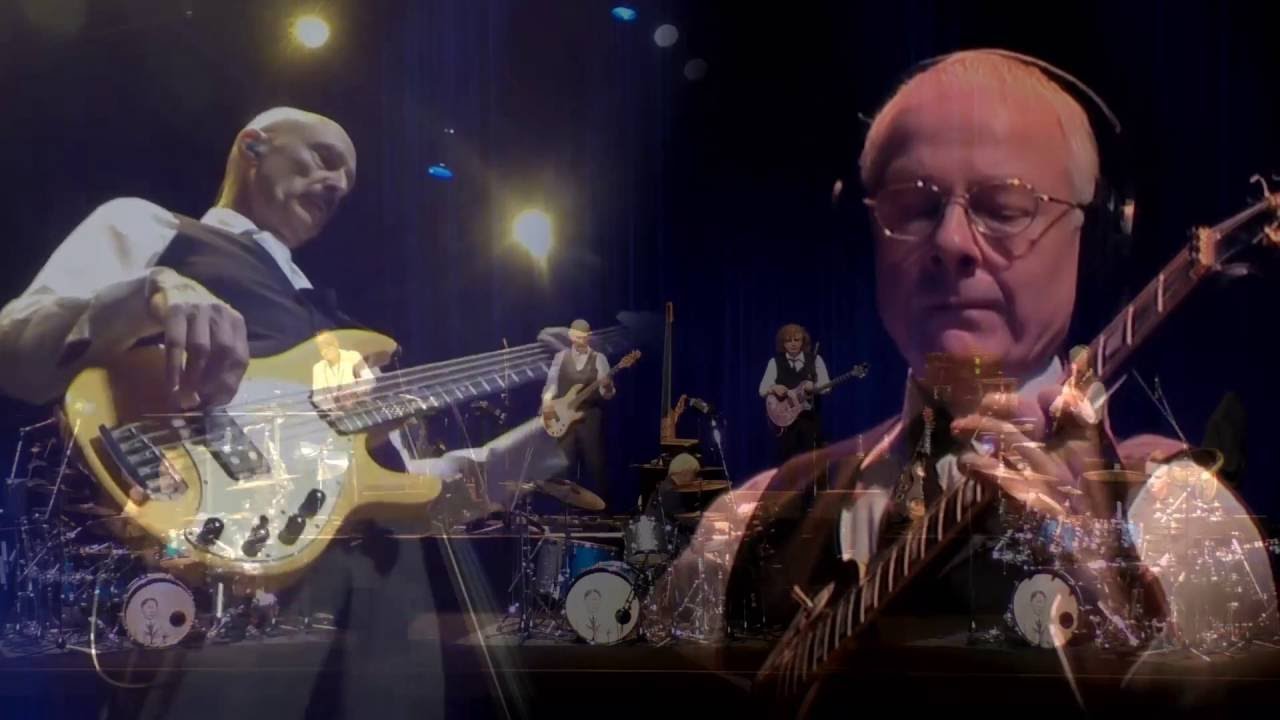

King Crimson vocalist and guitarist Jakko Jakszyk shares anecdotes from his revealing new autobiography, discusses his lost career as a footballer – and reveals what he said when he met Michael Jackson.

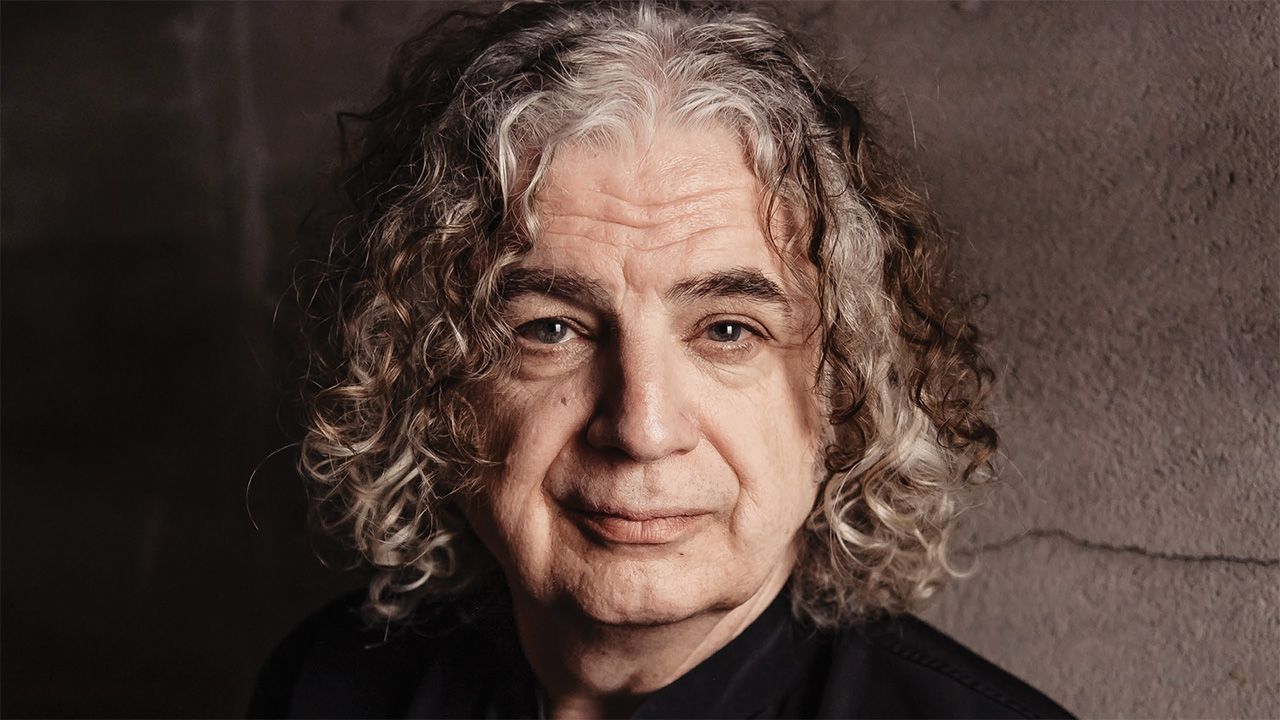

If Jakko Jakszyk’s music career ever ended, he’d make a great impressionist. An hour-long conversation about his fantastic new autobiography, Who’s The Boy With The Lovely Hair?, sees him mimicking everyone from Sir Richard Attenborough to Michael Jackson, both of whom are among the dozens of gobsmacking cameos in the book.

It tells the twin stories of his journey from teenage prog fan to latterday member of King Crimson, as well as the moving, sometimes frustrating saga of his attempt to track down the woman who gave him up for adoption as a child. Not for nothing is it subtitled The Unlikely Memoir Of Jakko M Jakszyk.

What made you want to write an autobiography?

I think it was finally discovering my father after 60-odd years of thinking about it, and this mad journey to get there. The musical story and the family story are bizarrely connected: it’s the whole sliding doors thing. Had my mother not had me adopted, would I have ended up in King Crimson? I might have ended up in America in some fucking country and western band.

Becoming a musician seemed to be third on the list of things you wanted to do, after football and acting.

They all seemed equally deluded, but being in King Crimson was the most ludicrous of all. I gave up on football after I stood at the side of the pitch for ages as a substitute and then they dragged me on for 10 minutes. Instead of going, “I’ll try for another team,” I just thought, “All right, that avenue’s closed.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

And then I joined the National Youth Theatre, and we did all these amazing productions. But the final straw was when I got a lift to an audition from this girl I knew. She wasn’t going to audition, but they gave her a job and not me. I was unbelievably arrogant back then.

Whether it was with your late-70s art-rock band, 64 Spoons, or as a solo artist in the 80s, mainstream success seemed out of reach. How frustrating was that?

Chiswick Records thought, “We need to sign something that’s going to be commercial,” and they foolishly thought it was me. But they gave me free rein to experiment and do loads of mad stuff, which you just wouldn’t be able to do these days.

I did once get a rave review in NME for a single I did called Dangerous Dreams [released in 1983 on Stiff]. Dave Robinson [famously mouthy Stiff founder] said, “The trouble with you, Jakko, is that you’re unfashionably heterosexual. Maybe you could hang out in [London gay club] Heaven. You don’t have to get off with anybody – just be seen there.”

Michael Jackson asked me about my shoes… I said the stupidest thing you could say to someone who’s sold 57 million records

There’s a fantastic anecdote about meeting Michael Jackson in a studio in LA in the late 80s while he was recording Bad...

I’d become friends with [musician/producer] Larry Williams and he invited me down. Michael Jackson was there, and he was being very quiet and deferential. At one point, I was sitting in this alcove at the back of the control room and he came over and started asking about my shoes. I ended up explaining what winklepickers were, which was surreal.

He asked me where I got them from and I said, “Shellys on Oxford Street.” And then I said, “The best thing is, they’re really cheap.” Which is the stupidest fucking thing you could say to someone who has sold 57 million records!

The book’s parallel story sees you tracking down your birth parents. How hard was it to revisit that aspect of your life?

I grew up knowing I was adopted. The house I grew up in was empty; there were no siblings. My dad beat me quite severely – I heard him talking about me as if he wished I wasn’t there. There were moments when I was really, intensely desperate to find out about these people who gave me up. But then, of course, things happen and you realise you’re dealing with reality.

You finally find your birth mother and her new family in America, but there’s no Hollywood ending.

At first you think, “Okay, they’re redneck Americans – they carry guns.” But with the advent of the internet, my brother was advocating for the genocide of all Muslims. And my sister was saying, “They’re not really racist.” There comes a point where it gets too much.

We’ve been recording studio versions of the new King Crimson material… Whether that comes out or lies in the vaults, I don’t know

You eventually cut off contact with your birth mother.

There were a lot of things involved with that. In the end, I wrote to her and said, “I’m never talking to you again.” I regretted it after I sent it, and then about two weeks later, my brother wrote this thing about being proud to be an American, proud to be a Trump supporter, proud to be a white supremacist. At which point any sense of remorse evaporated completely.

On a more positive note, you joined King Crimson in 2013. At what point do you stop thinking, “Holy shit, I’m in King Crimson!”?

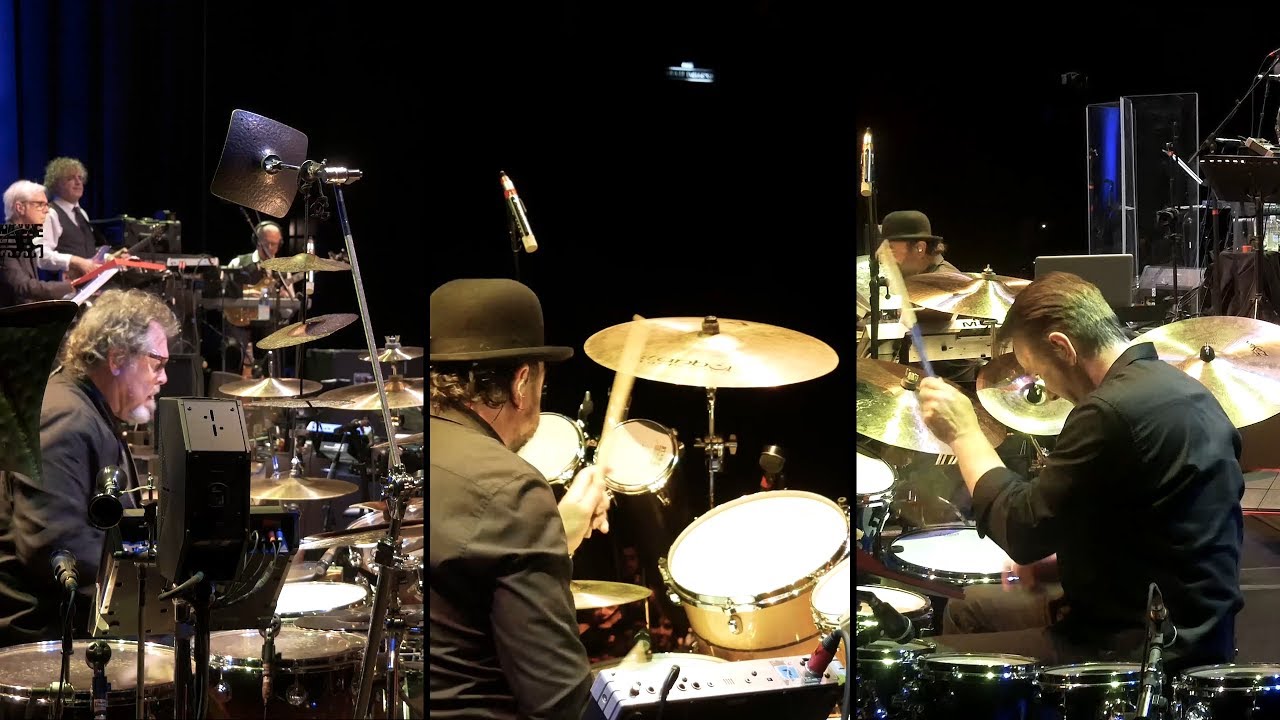

There was always part of me that thought that. I’d spoken to Robert Fripp a few years before that, but he wanted to pick my brains about Gavin Harrison. Then in 2013, he called and said, “I’m thinking of putting King Crimson back together; would you like to be the lead singer?” It was just like the maddest childhood dream come true. I phoned Gavin and told him. He said, “Yeah, he phoned me first. If I’d said ‘no’ he wasn’t going to phone you.”

Are King Crimson over?

The honest answer is, you’ll have to ask Robert. It’s all in his hands. He’s retired a million times before, but he is 78. One of the things we have been doing of late is recording studio versions of the new material [only previously played live]. We’ve used the live recordings as a template, and I’ve done guitars, overdubs and backing vocals. Whether that comes out as a King Crimson album or whether it lies in the vaults, I don’t know.

You’ve had an eventful life and career; you’ve met lots of incredible people – but you’ve never been a huge star. Would you swap it all for success?

No – I think I’ve done some pretty interesting things on the artier edges of it all.

Any regrets on not pursuing football as a kid?

No. That would have been a pretty short-lived career.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.