“Libraries gave us power,” booms James Dean Bradfield over delicately plucked acoustic guitar, his impassioned voice reverberating around the vaulted Art Deco auditorium of Newbridge Memorial Hall. The capacity crowd, mostly silver-haired couples and smartly dressed ex-miners, sing along politely. Others just smile proudly at the local boyo made good.

It’s a gala night of big voices and home-grown talents here in Newbridge, a former mining town in the South Wales Valleys. That means Broadway showtunes, creaky mother-in-law jokes and a headline set by Wynne Evans, the operatic tenor who found fame in the Go Compare advert. Classic Rock is here to celebrate the Hall’s newly re-opened theatre and cinema space, a sumptuously refurbished 1920s pleasure palace painted in scarlet and cream, following a decade-long fundraising campaign and refit totalling over £5 million. Warm tributes are paid to the venue’s chairman Howard Stone, stuck at home after suffering a heart attack on the very day of the concert.

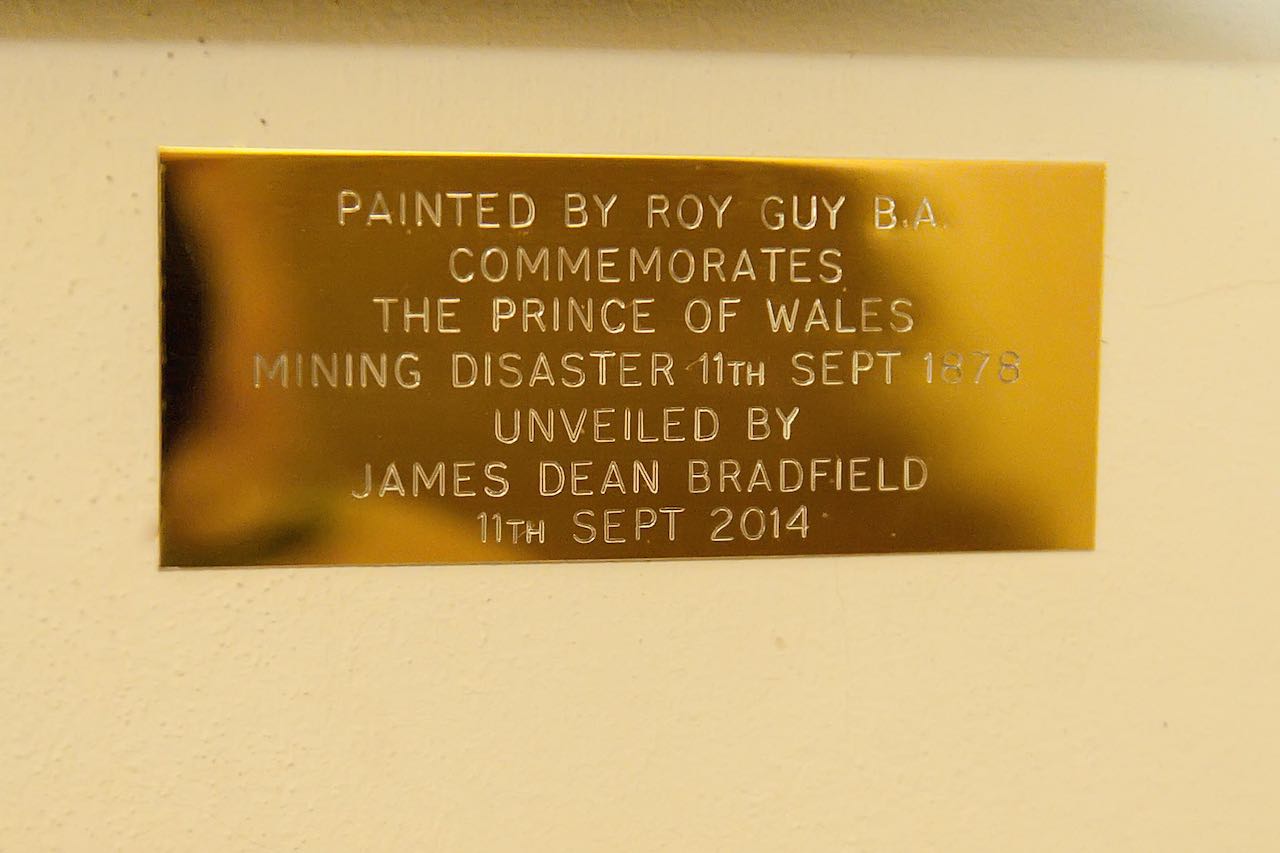

It may seem an incongruous way for the Manic Street Preachers singer to spend his 46th birthday, playing two solo songs midway down the bill of a traditional variety show. But Bradfield, who grew up in nearby Blackwood, has a history with the Memorial Hall, having worked behind the bar for three years in the late 1980s. He is now an honorary patron of the venue. Re-opened late last year, the Grade II listed building known locally as the Memo also has a refitted library and reading rooms downstairs, which lends extra resonance to the opening line of Bradfield’s rousing welfare-state anthem A Design For Life.

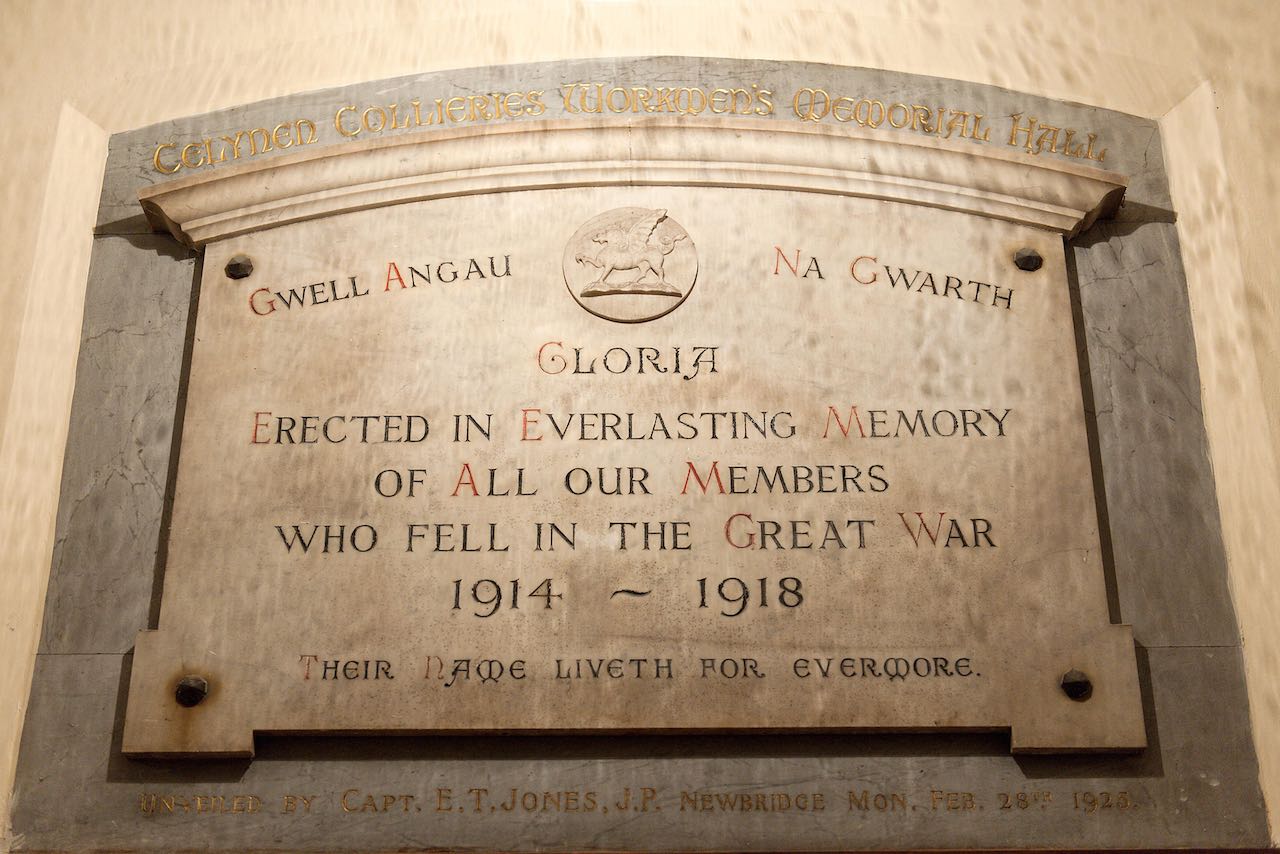

Built as a bricks-and-mortar memorial to the 75 local servicemen who died in World War I, the Memo was financed by individual donations from miners at the nearby Celynen Colliery. It opened in 1924, with a grand theatre on the upper level and a large bar with sprung dance-floor below. In the 1970s and 1980s, it served as a rock venue with bands like Dire Straits, Iron Maiden, Whitesnake and the Stranglers all passing through.

But by the time Bradfield worked at the Memo, the mines were being closed by Margaret Thatcher and the venue was sliding into disrepair, like many other miners’ institutes in nearby towns. The Manics singer has fond memories of lairy blues nights attended by local Hells Angels chapters. On one occasion, he walked in on Steve Marriott snorting cocaine in his dressing room, but declined the veteran rocker’s kind offer to join in the fun.

“I definitely decided I was never going to take drugs, after I saw that,” Bradfield laughs. “It was a Petri dish of humanity, working here. Some nights it could explode into something violent, but most nights you were exposed to something really homespun, warm and witty and earthy. It was the price of an education, as Keith Richards says. I got a musical education here. They were just really fucking lovely, warm, supportive people. And they gave me a job. And they always paid me.”

In 2015, Newbridge has that slightly forlorn air shared by many former South Wales mining communities. It has clearly seen better times. The high street has a tanning salon, betting shop, tattoo parlour, Baptist chapel and bunker-like police station. Terraced streets huddle on either side, clinging to the rugged valley slope. For Bradfield, re-opening the Memo is not just an act of cultural regeneration but a defiant political statement after decades of post-Thatcher decline.

“Parts of the Midlands, Northern England and Wales were changed forever by that fucking woman, and have never recovered,” he growls. “Swathes of working-class intellectuals came out of that mining generation, and she took it apart nut by nut, bolt by bolt. She actually took apart a culture. People gave money from their wages to build places like this! Can you think of anybody doing that now?”

The Memo’s project manager is Rob Jackson, who came aboard in 2004, around the time the theatre featured on BBC Two’s Restoration series. It narrowly missed first prize, but the show helped generate interest in the building as a TV location. Doctor Who and Sherlock both shot scenes there, even when the upper floor was a crumbling ruin. Several people even claim to have seen ghosts there. “The theatre had been closed for about 15 years when I arrived,” Jackson recalls. “It was like Tutankhamen’s tomb. But it was quite magical walking into the place, I could just see the potential.”

Jackson now runs the refurbished Memo as a social enterprise, ploughing all profits back into the building. He has ambitious plans for the year ahead, including an educational heritage experience aimed at schoolchildren and an exhibition of photographs by Newbridge-born Angus McBean, who left Wales to shoot rock and film royalty, including the iconic balcony shot that adorned the first Beatles album.

“I’d particularly like to bring back a lot of music to the building,” Jackson says. “It has an incredible musical history. Ivor Novello’s mother first sang here. Joe Loss played here, and quite a few jazz bands. In the ‘70s and ‘80s it was on the circuit – Motorhead, Duran Duran, Doctor Feelgood. We’ve got Buck & Evans playing next weekend, which is already sold out. We are talking to other bands, and also looking a developing a music festival here. It’s not going to be easy, but I think we’re moving in the right direction.”

After the show, Bradfield warmly greets a throng of fans in the public bar, signing autographs and shaking hands. Local boy Stefan tells me about the Memo before it was refurbished. “The Art Deco cinema was in bits,” he nods. “It was like walking around a haunted house, really derelict. It’s lovely to see what it’s become.”

A middle aged couple who have travelled up from Cardiff remember the building’s reputation for live rock shows. “It was a legendary venue,” says Patrick.“I just think it’s fantastic, with so many theatres closing, to have something like this opening,” adds Jenny.

Based on the sheer beauty of the restoration and the warmth of the local audience, the Memo will hopefully reclaim its place on the live rock circuit. As an honorary patron, Bradfield is committed to helping it thrive, but he also sees the building as a crucial cultural catalyst, much like the miners’ institutes where the Manics educated themselves and played their early shows. Libraries gave them power to think locally and act globally.

“You don’t need to go to Cardiff, or London, or Bristol, or Newport,” Bradfield insists. “You can actually do something like we did. We formed ourselves here. Whether you’re a plumber or a painter or a roofer or a musician like me, you can actually re-mould yourself in the town where you were born and still be part of it. A place like this will help.”

Visit the Newbridge Memo Website.