Searching for a true heartland American band, you need travel no further than Cleveland, Ohio, home in the late 1960s and early 70s to the James Gang. Like the legendary outlaws they took their name from, the James Gang were a bunch of mavericks whose reputation would far outlast their actual achievements.

The short time they were together resulted in one of the most lasting stories in the folklore of rock’s Old West. And it was a story that would have a surprise final chapter, when Dave Grohl asked the James Gang to play at the Taylor Hawkins tribute show at London's Wembley Stadium.

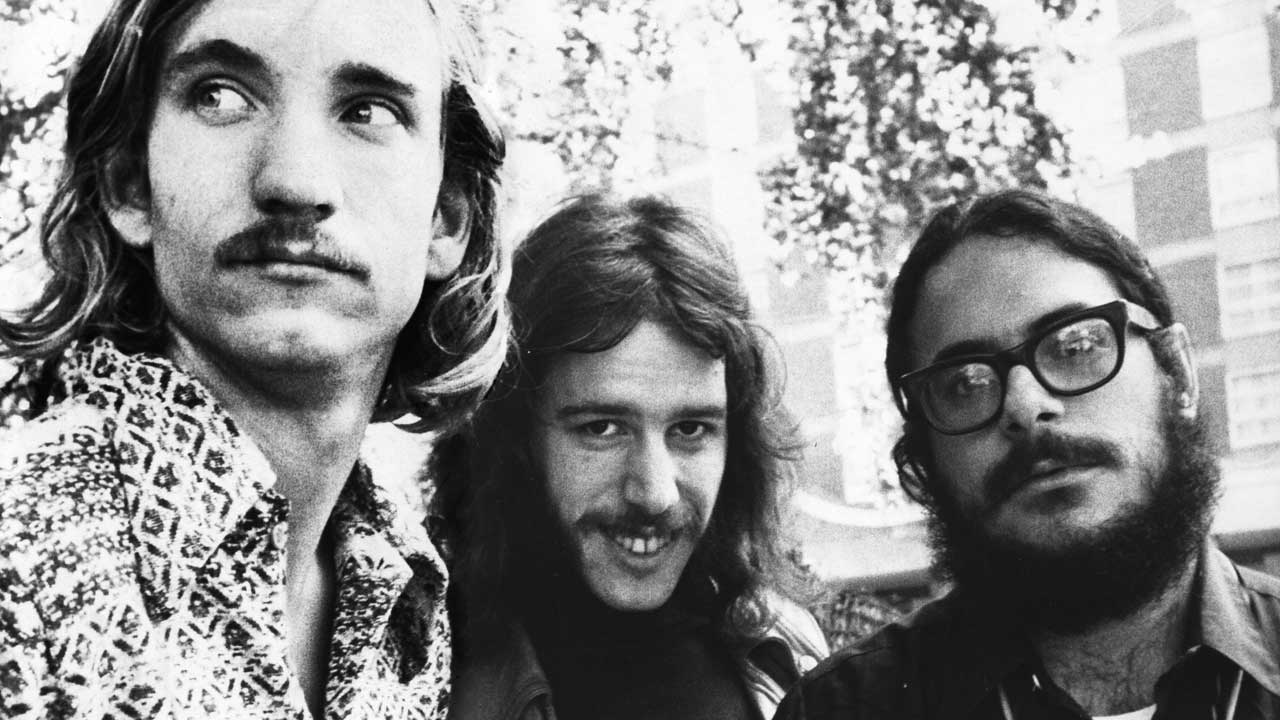

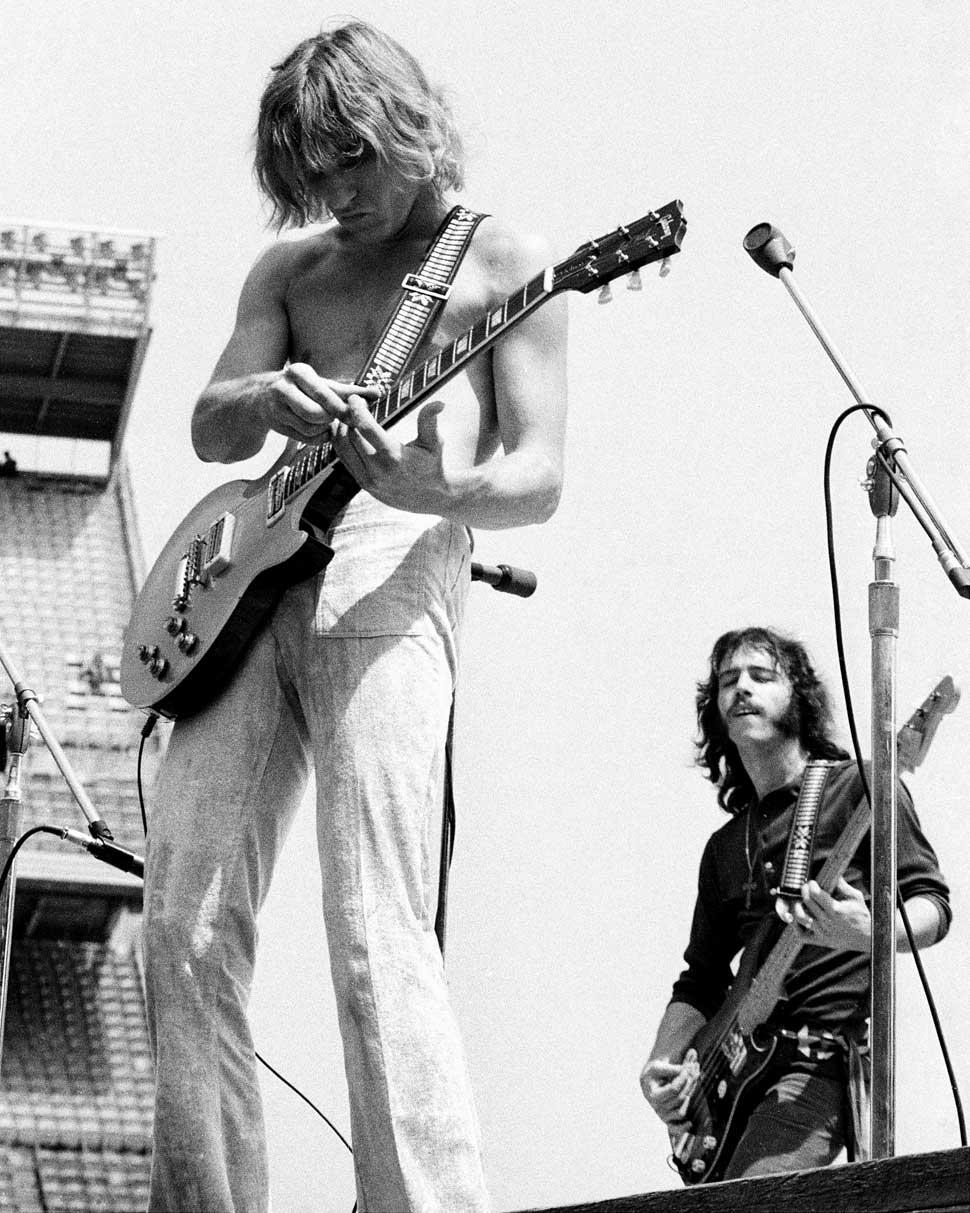

Starring a 22-year-old singing, songwriting, officially amazing guitarist named Joe Walsh, the classic three-piece James Gang line-up – drummer James ‘Jimmy’ Fox, guitarist Walsh and bassist Dale Peters – only recorded three albums together (or four if you count their live album). But when the Gang opened for The Who at a show in Cleveland in 1969, Pete Townshend liked them so much he took them home with him for a tour of the UK, declaring them “the best new American band I’ve seen” and Walsh in particular “a genius”.

“We never thought about tomorrow, only what was going on today,” says Fox, founding member and eponymous leader of the Gang. “Maybe that’s why we never quite made it. But it sure was a lot of fun while it lasted.”

The band had started in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1966, when the 19-year-old Fox decided he’d changed his mind about being the new Art Blakey and wanted to be Ringo Starr instead.

“The Beatles changed everything for me,” says Fox, speaking over the phone from his Ohio home. “I was a big Buddy Rich guy until I heard Ringo. Then I discovered Cream and Ginger Baker, who was spectacular. That’s how the James Gang came about.”

If Joe Walsh was the onstage frontman of the band, Jimmy Fox was the heavy presence at the back that allowed his guitarist to fly. A bearlike figure in full black beard and shades, Fox had a steady, rolling style that was percussive without being showy, the groove-laden halfway point between John Bonham and Keith Moon. As Dale Peters puts it now: “Jimmy was the guy who kept it all together, for all of us. He’s still that way now. He’s the guy who always take care of business.”

Starting as a five-piece, with an additional guitar and keyboards, the early James Gang drifted through various line-ups before becoming a trio, almost by accident. “I don’t quite remember how we lost that keyboard player,” laughs Fox. “His parents may have made him quit. He just stopped showing up.”

Carelessly, they lost another member just before they were due to open for Cream at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, in 1968. “When we got to Detroit the other guitar player wasn’t there either!” says Fox. “We were sitting around looking at each other, like, ‘Damn! We don’t have enough money to get home! What are we gonna do?’”

Fortunately, they still had an ace up their sleeves. Joe Walsh had dropped out of Kent State University and was already veteran of half a dozen different acts before he hooked up with Fox. Recalled now as the party-hearty guy who later struck solo gold with Rocky Mountain Way and Life’s Been Good To Me, before going on to put real feathers on the chests of the Eagles, the young Walsh was a far more serious and dedicated musician than his later persona might suggest. At the time of the Grande Ballroom show, he thought of the James Gang as just another band he was passing through on his way to something better.

“We thought, ‘Oh well, this’ll be our last job,’” Walsh later recalled of that fateful night. “It was a make it or break it night and we were deadly scared. It was purely experimental on stage that night, three guys trying to get together what five guys normally did. But we got an ovation.”

“He was just a pure guitar player,” says Fox, “who could also play keyboards, sing, write. But it wasn’t until we went on that night as a three-piece that we realised how much Joe could do. By the end, we did seven encores. We ran out of material and were forced to play Jimi Hendrix tunes. Imagine that, opening for Cream and finishing with Hendrix tunes?"

Fully saddled up, the Gang rode home to Ohio and never looked back. Playing almost every night in every dive in the north-east Ohio area, they were soon talent-spotted by another fast-rising star, ABC Records house producer Bill Szymczyk – most recently responsible for such giant hits as BB King’s The Thrill Is Gone – who memorably described the Gang as “a three-piece that sounded like a 10-piece”. Especially impressed by Walsh, Szymczyk went back his paymasters at ABC and persuaded them to sigh the band for a $1700 advance.

The first Szymczyk-produced James Gang album, Yer Album, was released in March 1969. It was a grab-bag of artful originals – not least the Walsh-penned Take A Look Around, which showed a delightfully melodic side to the band – and workmanlike covers, such as Lost Woman, which took the Yardbirds original and railroaded it into the kind of barnstorming boogaloo that would come to represent their harder-edged live act.

“We weren’t thinking about how to best represent ourselves on a record,” recalls Fox. “We were still just excited to even be making a record.”

All that is save for original bassist Tom Kriss. In another example of what was to become the defining – and ultimately deflating – motif of the James Gang’s stuttering career, Kriss decided he “didn’t like the music” and left just as interest in their debut album was gathering momentum. “Joe said to me one day: ‘Have you heard Tom actually say anything lately? Cos I haven’t heard him speak a word for about two months,’” says Fox.

Sure enough, when the pair collared Kriss about his sudden muteness, the bassist confessed he was “hearing something different in his head and wanted to leave”.

Enter the final member of what is now regarded as the classic James Gang line-up: bassist Dale Peters. “Any great band is a little bit of talent and a ton of chemistry,” says Peters. “We could just play really well together from the get-go.”

The first album by the Fox-Walsh-Peters line-up, James Gang Rides Again, was released in 1970 and found the band beginning to crest their own wave. “Rides Again was just dressing room jams, really,” says Peters, who co-wrote five of its nine tracks. “We just knew where each other was going musically. Joe started playing something. Jimmy and I would just pick it up. We had just been playing clubs continuously all over the country while we were making that album, so it felt very easy to do.”

Their most complete collection – from homespun rock-funk-boogie band compositions like Woman to beautiful acoustic Walsh tunes like There I Go Again and, most ambitiously, The Bomber, a seven-minute epic that began with the original Closet Queen before moving seamlessly into Walsh’s demented take on Ravel’s Boléro, before climaxing with jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi’s Cast Your Fate To The Wind – Rides Again also contained the track that would become the Gang’s signature anthem, Funk No.49.

Now a staple of classic rock radio in America and a popular soundtrack choice in a number of movies, TV shows and video games, Fox says he is still “kind of amazed” by the afterlife that one track has bequeathed the Gang.

“I was sitting there just a few weeks ago watching Joe play it with the Eagles,” the drummer says, “and I turned to Bill Szymczyk, who was sitting behind me, and I said: ‘Who the fuck knew?’ Cos at the time it was just another good tune we had that would go down great with audiences.”

Not just in Ohio either. Already known as the best warm-up band this side of the Mississippi, with Funk No.49 now blasting from the newly established FM radio formats then fuelling the more album-oriented rock sound of Midwest America in the early 1970s, and national recognition coming their way from beard-stroking arbiters of the new good taste like Rolling Stone and Creem, suddenly it was deeply cool to want to be a follower of the James Gang.

When Pete Townshend then invited the band to open for The Who on their 1970 UK tour, word was truly out in a way that it would never be for similar heartland American bands of the same era, like Grand Funk Railroad.

“We were hip without really knowing it,” says Fox. “It was cool being able to check in with someone like Townshend, but inside the band not much changed – we were still playing every single night, never taking a break.”

This appetite for the road belied their image as what Fox describes now as “a bunch of rag-tag guys, hanging loose, just getting up there and grooving. That was what the music said when we played but in fact we were working real hard.”

Even their drug use was minimal, considering the wild era they came from. Another Fox belly laugh. “We had the hair and the motorcycles and the guitars but that was pretty much it. In 1969, there was some weed around. There was some alcohol. I don’t think anyone had seen cocaine, though, until about 1970. Even when we did, it was not something that was life altering. There was some experimenting with LSD too. But it was very, very minor. Later, those things became more of a problem for Joe. But in those days we were straighter than many. The influences were more direct. They weren’t artificially induced.”

Nevertheless, the pressures on Walsh, as the creative wellspring of the James Gang, were starting to take their toll by the time their third album, simply titled Thirds, was released in April 1971. It was recorded while they were on the road, with the band studiohopping across five different locations.

“Joe was kind of tired at that point of doing everything,” recalls Peters. “He was the main writer. He was singing lead, he was playing lead, and he wanted us to be more involved in the writing. Or maybe he wanted to do less of it himself.”

The upshot was an uneven album featuring only one group composition, the throwaway Yadig?, plus four Walsh tunes – the best of which, the raucous Walk Away, and the sublime Midnight Man, were as good as anything he would ever write – and two no-biggie songs each by Fox and Peters.

“My own opinion of my own tunes? I didn’t think they were very good at the time,” admits Peters. “Joe was just a better writer than we were. He had some tunes that I think we didn’t use. But he was like, ‘No, I’m starting to do everything, blah bah blah, I want you guys to come up with some tunes.’”

Walsh initially agreed to speak to Classic Rock, though he backed out at the eleventh hour, blaming commitments with the Eagles. While he has never been explicit on the subject, the guitarist has hinted that it was the inability of the three-man Gang line-up to accommodate the guitarist’s more melodic side as a songwriter and musician that caused him to leave. Live, lush musical moments like Midnight Man simply could not be replicated.

“I was frustrated at having several musical ideas that were difficult to do with just three people,” he admitted back in 1982. “I was burning out through having played with them for three years and the group developed and got as far as I thought it ever would.”

“Joe always wanted it both ways, and I think that’s admirable,” says Fox. “He had the ability, he had the chops, he had everything it took. And he has since proven that you can have it both ways. When you reach a certain level of talent, some of the labels slip away. And that’s what happened to Joe. Joe can play anything with credibility.”

In order to realise that ambition, though, Walsh had to strike out on his own – which he did, shortly after the release of his final James Gang album, Live In Concert, recorded at Carnegie Hall, New York, in May 1971. Like so many other heartland American artists of the period, the live Gang album also cemented the idea that the group’s albums never fully captured the excitement of the band playing in the flesh. It was also, tellingly, their first – and last – foray into the US Top 30, the beginning of what should have been their mainstream breakthrough. Except that when Walsh left, so did whatever commercial momentum that had built up behind them.

“There was also frustration at having a lack of control of the quality of the music,” said Walsh. “It turned into a successful group and therefore it turned into big business with expensive ticket prices and heavy schedules and not so much creativity as there had been at the beginning. There were no real bad vibes when I left though.”

Well, almost none. “It was horrible!” says Peters now. “We had found our groove and we were playing great together, just everything was working. But Joe was unhappy for whatever reason, and he left and so we had to completely regroup. It was pretty much almost impossible. You can’t really replace the main person in a three-piece group and expect it to still work.”

Fox adds: “I called Pete Townshend and asked what I should do and he said: ‘As far as I can see, you just need to find yourself a kick-ass guitar player.’ Of course, it wasn’t as easy as that. That’s like saying if Pete left The Who, all you needed to do was replace him with a kick-ass guitar player.”

Admirably, Fox and Peters decided against following Townshend’s advice, bringing in two extra players – former Mandala members singer-guitarist Domenic Troiano and singer-percussionist Ray Kenner – with whom they released two further James Gang albums, Straight Shooter and Passing Thru, both in 1972. Neither contained the inspirational fire of the Walsh era though and the band broke up, dispirited and now some way off the critical radar.

“We made some nice stuff with Dom and Ray,” says Peters, “but after Joe, we weren’t really accepted. People missed the original line-up. I missed it too.”

There was a last-ditch attempt to rekindle what they had when Walsh personally introduced them to a brilliant but wayward young hotshot guitarist named Tommy Bolin, but that too was a postscript doomed to failure – though for different reasons.

“Tommy was quite a character,” says Peters. “A rock star 24 hours a day. He was just a very intense guy. And actually we made two pretty good albums with Tommy. But once you knew Tommy, you knew that the end was inevitable. He was absolutely on a self-destructive path that was obvious to everybody. Really a shame, cos he was a very nice guy, and incredible guitar player. But he was absolutely burning the candle at both ends. After the gigs he’d go out, come back at four or five in the morning, start again. I mean he was just going full tilt 24 hours a day."

The errant young guitarist was certainly going too fast for the James Gang to hold on to him, and in 1974 he left the band, initially for a solo career, but then for Deep Purple – and ultimately an ignominious death from a drugs overdose. Fox and Peters continued with other musicians until 1977. By then the drummer knew it was all over.

“I just didn’t have the heart to carry on,” he says simply. But then, none of the great outlaws of rock’s Old West lived long enough to enjoy a happy ending. And where would have been the fun in that for the rest of us, anyway? Instead, the James Gang are now rightly remembered as what they were: live fast, die young, rootin’, tootin’ rock cowboys from the good ole days before the rules had been written and all the maps drawn.

“Back then there was no thought for how to be successful,” says Fox. “It was all about the next gig – until one day there was no more next gig.”

Eventually, there were other gigs. The Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2001. The Beachland Ballroom in Cleveand four years later. And, in 2006, a full reunion tour with Walsh back on board, the original lineup augmented by a keyboard player and three backing singers.

“They’re like everything we should have done with Joe back in 1971,” says Fox. “I was so in love with the idea of us being a trio I couldn’t get my head around bringing in extra musicians, which we do now, of course. But those were different days, you know?”

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 168, in September 2013.