From the Griffith Park Observatory, high on the slopes of Mount Hollywood, the view is spectacular. The vast metropolis of Los Angeles is spread out below, with the Pacific Ocean visible to the south west. This was the location chosen by Jane’s Addiction singer Perry Farrell for his band’s first encounter with the British rock press: an interview and photo shoot for Sounds in June 1988.

The grounds of the observatory were deserted when photographer Mary Scanlon and I arrived at the designated time: eight o’clock in the morning. But for Farrell, it wasn’t early – it was late. He hadn’t slept since he called me at my hotel room to arrange this meeting, a call that woke me at 4am.

Perry Farrell was one of LA’s night people. As the name of his band suggested, he was a drug fiend, operating on junkie time. He looked like it, too – rail-thin and white as a ghost, his eyes hooded, dreadlocks long and ratty. With his outsized nose and broad mouth, he looked a little like Mr. Punch.

On this morning he was dressed in freaky Melrose Avenue thrift-store chic: LA Lakers T-shirt with the sleeves cut off, chequered trousers and a woven hat that resembled a grandmother’s lampshade. He offered a bony handshake before introducing the rest of the band. Guitarist Dave Navarro, girlishly pretty and all in black, with sunglasses and a wide-brimmed hat, had an offhand air about him. So too did bassist Eric Avery, whose military jacket and beret gave him the appearance of a student revolutionary. More outgoing was drummer Stephen Perkins, tanned as a surfer with a mop of dark curls. But it was Farrell who did pretty much all of the talking.

It was immediately apparent that he controlled the band. Before we began the interview, Farrell gathered the others around him for a whispered briefing. And while they posed for photos, he explained why he had brought us here: not only for the views but also for its connection to a golden era of Hollywood and, more specifically, doomed actor James Dean.

The darkness of the Dean story appealed to Perry Farrell. And during the conversation that followed, he had other disturbing tales to tell – true stories that had informed songs from the new album that Jane’s Addiction had just recorded. There was Jane Says, written about the woman after whom the band were named: her inability to escape a life of drugs and domestic violence. And there was Ted, Just Admit It… a song addressed to serial killer Ted Bundy, in which Farrell spoke the title of the album: Nothing’s Shocking.

It would be two months before the album was released. At the end of the interview, Farrell handed me a tape of it. This was not an official record company advance copy but a rough mix, with the track listing in his ragged handwriting.

Nothing’s Shocking was the most powerful rock’n’roll record since Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite For Destruction a year earlier. But what Jane’s Addiction had was a whole different trip to GN’R. There was an art-rock sensibility at the core of Nothing’s Shocking, a taste for weirdness and exotica. Their palette extended from Led Zeppelin-inspired riffing to the post-punk of Joy Division, The Cure and PiL, from goth rock to funk, dub reggae and swinging jazz.

At this time there were numerous bands exploring new forms of rock music – Pixies, Butthole Surfers, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Ministry, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr., Faith No More and the bands in the nascent Seattle scene. But with Nothing’s Shocking, Jane’s Addiction would emerge as the standard-bearers in the rise of alternative rock.

As Perry Farrell said that day in 1988: “We started from the street and worked our way up. So, you get that attitude. And when it boils down to it, we don’t really care what people think. I’m doing what I like to do.” And he was ready for fame. “In the rock’n’roll field,” he said, “I pretty much have it made, because the more arrogant a person is in rock’n’roll, the more hyped they are.”

More than a quarter of a century on from the release of Nothing’s Shocking, the life of Perry Farrell is very different to what it was back then. At the age of 55, the singer is a wealthy man who lives with his wife Etty Lau and two young sons, Hezron and Izzadore, in an upscale neighbourhood of LA. “I have a beautiful home,” he says, “close to the ocean.”

It’s 23 years since I last spoke with Farrell, when Jane’s Addiction were on tour promoting their second album Ritual de lo Habitual. It was a period in which the band had already begun fragmenting, partly as a result of the singer’s ongoing use of hard drugs. Farrell no longer has a drug habit, but he does not speak out against drugs as most reformed rock stars do: “I think narcotics, done properly, are one of the great benefits that God has given us – opium and cocaine. They’re wonderful.”

And there’s another sense in which he’s still the same old Perry Farrell. He’s still a prodigious talker. After a rambling ten-minute reply to my first question, he says, a little apologetically: “My answers are very long. I hope, at least, they’re interesting to you.”

What he reveals in an hour-long conversation is what shaped him as a person and what shaped Jane’s Addiction and Nothing’s Shocking. He was the lonely child who turned to music as an escape; the sensitive artist who developed a huge ego as leader of his band; the hedonistic intellectual whose wild creativity did so much to redefine rock music; the misfit with a desire to become a legendary rock’n’roll star. “I wanted to be loved and admired,” he says. “I wanted to be thought of as The Great One.”

Farrell experienced a deeply troubled childhood. Born Perry Bernstein on March 29, 1959 in Queens, New York, he was just four years old when his mother, an artist, committed suicide. “I don’t really have much memory of her,” he says.

According to Farrell, at the time when his mother took her life, his father was involved in an extramarital relationship. “The woman whom my father was having the affair with ended up being my stepmother.”

In his adolescence, he found solace in music. Favourites included The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Sly & The Family Stone and David Bowie. “The value I placed on music was so high,” he says. “It was everything to me. Growing up, I needed music to fall into. I was a skinny kid. I didn’t have a lot of friends, by choice. I didn’t like hanging out with the cliques. I saw most kids as dumbbells. I didn’t like the way they viewed women. So I’d listen to records. I was a loner.”

His family moved to Miami, where Farrell attended high school. And after his graduation, he fled to California. For a time he lived in a car. He loved to surf, and earned money in construction, but his primary focus was music. In 1981 he became the singer for Psi Com, a post-punk band that gigged around LA with other underground acts such as the Chili Peppers and X. But by 1985, Psi Com had made just one EP, and Perry – now having rechristened himself Perry Farrell, a pun on peripheral – was in his mid-20s and running out of time if he was going to realise the grand vision in his head. “I wanted to be in a great group that would alter the history of music,” he recalls. “A band that would change the rotation of the Earth.”

He found Avery first, and then, after various line-up changes, Perkins and Navarro. The band were named after Jane Bainter, with whom Farrell shared a house in Hollywood. “She was a full-blown addict,” he says. “Everybody in that house was. We had sixteen people living there – mostly musicians and their girlfriends. The house was so crooked, you could put a ball on the floor and it would roll to the other end of the room. I lived in the attic, and in the garage we made a jam room where the band rehearsed. We lined the walls with egg cartons and carpet, but it didn’t quite deaden the sound. Cops were coming to the house every other day because of noise complaints. But we had so much fun in that place. It was one of the greatest times of my life – one of the happiest times I can remember.”

For three years, Jane’s Addiction played in clubs. The band was, like Psi Com before it, a part of what Farrell refers to as “the underground Los Angeles” – a bohemian freak scene in which musicians mixed with artists of all kinds. “The underground was where I wanted to be,” he says. “That’s where the intelligentsia was, where the gay people were, the madmen and the junkies, and I loved them all.”

What little money Farrell had, he spent on drugs – principally, a cocktail of cocaine and heroin. “We were speedball addicts,” he says. “I would carry needles in my pockets. I would find a bathroom wherever I was and slam a speedball – I’d have a couple of them in my pocket. And then I’d go home, where I had a bag full of them. I was as wild as a young man could be.”

But more than drugs, Perry Farrell wanted his new band to revolutionise rock music. “Rock’n’roll had been around for thirty years,” he says. “It was almost impossible to come up with a new sound, a new way. But I had to have it. We had to do it. And what happened was, I saw what I didn’t like.”

When Jane’s Addiction were a club act, Mötley Crüe were the biggest stars and swinging dicks of the LA music scene. The two bands had one thing in common – drugs. Beyond that, they were worlds apart. “You could be a good musician,” Farrell says, “but if you were writing about crap, like you’re in league with the Devil, and you looked like some whore on Hollywood Boulevard, I couldn’t have cared less. With hair metal, there was no ingenuity.”

What Farrell loved was the heavy rock of the 70s: Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Bad Company. “The great, true rock music,” as he now calls it. And this classic rock influence was evident on the first album recorded by Jane’s Addiction. Released via independent label Triple X in May 1987, this self-titled album was cut live at Hollywood club The Roxy and included versions of the Rolling Stones’ Sympathy For The Devil and the Velvet Underground’s Rock & Roll. Also featured were two songs that would be remade for Nothing’s Shocking: Pigs In Zen and Jane Says. The live album was a marker. As Farrell told me in 1988: “We could establish our style, and record companies would know who we were.”

When the band subsequently signed to the Warner Brothers label for what was reportedly one of the largest advances of the time – $300,000 – Jane’s Addiction were soon being touted as the next big band to come out of LA after Guns N’ Roses. But Farrell wasn’t flattered by the comparison. “To be honest with you,” he says now, “we kind of put our noses in the air at Guns N’ Roses.”

For Farrell, being the hot new thing in LA wasn’t enough. “I saw us as part of this line,” he says. “A line that went from The Beatles and the Stones and Led Zeppelin and The Who to The Clash and Siouxsie And The Banshees and Joy Division.” And with Nothing’s Shocking, Farrell set out to blow people’s minds. “We wanted this record to sound like it was from outer space.”

When Farrell talks about what set Jane’s Addiction apart from every other rock band of the era, he’s unequivocal. “I have a very identifiable voice. It’s a unique sound, the divinity of my vocal cords. In that sense I was gifted with this beautiful luxury. So everything I built around it was to protect the integrity of that voice.” He knows how arrogant this sounds. “Don’t get me wrong,” he says. “My band were great players.” But his phrasing is telling: “My band.”

What they created on Nothing’s Shocking was rock music of startling originality and eclecticism. “I never wanted to write a song like somebody else’s song,” Farrell says. “I wanted to add something – like, let’s add salt to the caramel. You’re a scientist. You know that when you put different ingredients together, they’re combustible. So you combine rock and reggae and electronics – those are the three main ingredients I worked with on Nothing’s Shocking.”

At its core, this was a rock’n’roll record. There were echoes of Zeppelin in Mountain Song and Pigs In Zen, while Jane Says was a simple acoustic track with a 60s folk-rock feel. The reggae influence in Ted, Just Admit It… came from dub masters such as King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. “Dub reggae,” Farrell says, “is beautiful, spiritual.” There was a hazy, psychedelic beauty to Summertime Rolls; a funk propulsion to Standing In The Shower… Thinking. And what Farrell said in 1988 – that his hero, unlikely as it seemed, was Frank Sinatra – was borne out in Thank You Boys, a tongue-in-cheek homage to the golden age of swing.

Farrell’s lyrics were as unique as his voice. In our first interview, he explained the meaning in certain songs. Had A Dad was a meditation on God: about life, as he described it, as “a transference of energy through semen”. And then there was Ted, Just Admit It…

One of America’s most infamous mass murderers, Ted Bundy was on death row when this song was recorded. Farrell said: “It’s called Ted, Just Admit It… because he has never admitted to his guilt – even though his bite marks were on the bodies of the women he bludgeoned to death.”

What he also reveals, after an uncommonly lengthy pause, is that on Mountain Song he wrote, in oblique terms, of his mother’s suicide. “The song goes: ‘Cash in now, honey… Cash in Miss Smith.’ Cashing in is taking your own life, and Miss Smith was my mother’s maiden name.”

What he remembers most clearly about the making of Nothing’s Shocking was the spirit of adventure in the band. “We were young people in our twenties,” he says. “And at that age, you’re rolling dice, you’re taking risks. If it fails, it’s not too bad because you don’t have too far to fall. You have all the energy in the world to stay up for days at a time and you wouldn’t even feel it.”

And yet, even at this early stage, Farrell sensed that in his desire to have things his way, he was isolating himself. “If I had seen it as my band,” he says, “we probably wouldn’t have fought so much. But in the end, I must have my way. I should have been a solo artist, but people love groups.

“I remember recording my vocals without the band. There was already a strain and a separation beginning to happen. And that was going on while we were making the album…”

Nothing’s Shocking was released on August 23, 1988. A review in Rolling Stone stated: “The band is great and full of shit – often at the same time.” But most other critics hailed the album as a modern rock masterpiece, and Sounds put Jane’s Addiction on the cover. But great press could only get them so far. One month before the release of Nothing’s Shocking, Guns N’ Roses hit the top of the US chart with Appetite For Destruction. Nothing’s Shocking peaked at No.103.

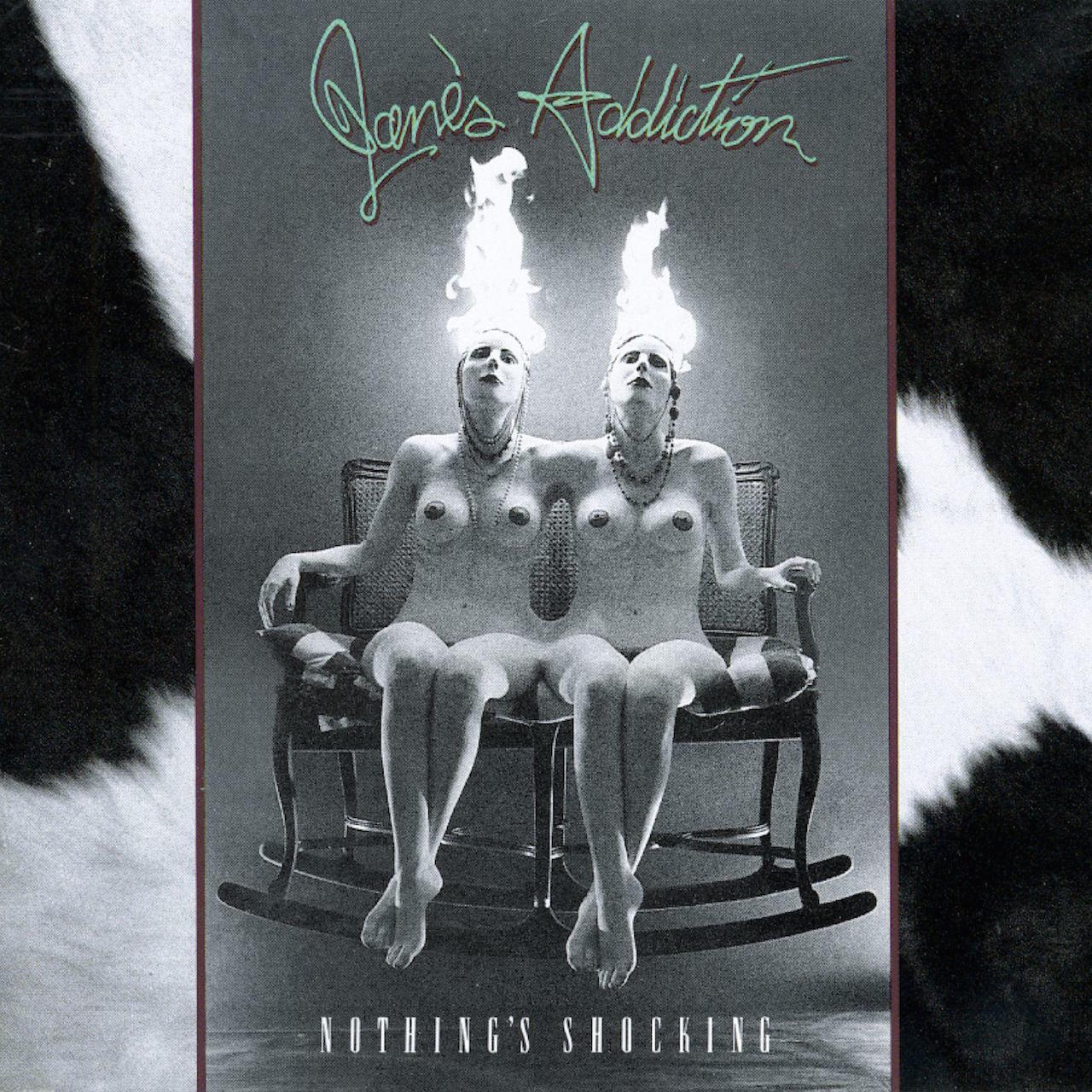

Part of the problem was the album’s cover, which featured a piece of artwork made by Farrell – a pair of female conjoined twins, naked, with breasts exposed and their heads on fire. It was modelled on the singer’s girlfriend, Casey Niccoli. “It came from a dream,” he says. “I saw this girl, a Siamese twin. I say ‘girl’ because it’s one being, almost. She’s on a swing and her hair is on fire. It just came around when it was needed.”

In the US, nine out of the 11 leading music retailers refused to stock the album. Similarly problematic was the video for the album’s first single, Mountain Song. It contained scenes of Farrell and Niccoli lying nude on a bed, and was banned by MTV.

Jane’s Addiction toured Nothing’s Shocking for nine months, on and off. On stage, they could be brilliant, as their first UK performance proved. On September 24, 1988, they supported Fields Of The Nephilim at London’s Brixton Academy, and at the end of their set, the audience demanded an encore – at which point, the power was cut and the house lights switched on. Farrell refused to give in, bringing the band to the front of the stage, where they bashed away at a single drum and he screamed over the racket without the aid of a mic.

The first-year sales of Nothing’s Shocking were modest: approximately 200,000 in the US. But it was an album that placed Jane’s Addiction at the forefront of a new era in rock music. The big breakthrough came with the follow-up, Ritual de lo Habitual. Yielding a minor hit in Been Caught Stealing, the album reached the US Top 20 in 1990. It made Jane’s Addiction the first alternative rock band to find any sort of mainstream success. “But of course,” Farrell says, “it couldn’t last.”

In October 1991, with the singer having developed a crack addiction, he could no longer keep the band together. “Your bandmates love you when you’re becoming successful,” he says. “But the animosity starts with the wear and tear – hard work and touring. You should feel that you’ve been blessed, but no, you don’t. Your personality starts to change. You become a baby. Selfish. A wise-ass.”

Those clashing personalities brought Jane’s Addiction to a premature end in 1991. Lollapalooza, the music and arts festival founded by Farrell, would be their swansong. Since their initial split, there have been several reunions. An initial comeback album, 2003’s Strays, was belatedly followed in 2011 by the dark and ethereal The Great Escape Artist. The band have subsequently stuck around, albeit without original bassist Eric Avery. In August, they will play the whole of Nothing’s Shocking at two dates in the UK.

The fact that Jane’s Addiction are still together in 2014 is, Farrell says, a testimony to the “great constitution” of its three original members. Above all, it’s a testimony to what they achieved with Nothing’s Shocking – the groundbreaking album that made Jane’s Addiction, and made Perry Farrell.

“It’s one of the great accomplishments of my lifetime,” he says. “I will always be welcome around the world to perform songs from Nothing’s Shocking. I feel so fortunate that that record was created.”