Thomas Wolfe was right: you can’t go home again. In August 1970, when Janis Joplin returned to Port Arthur, Texas for her tenth high-school reunion, she told a local reporter that she was attending “just to jam it up their asses” and to “see all those kids who are still working in gas stations and driving dry-cleaning trucks while I’m making fifty thousand dollars a night”.

Some of those same kids once called Janis a pig and a weirdo and threw pennies at her, teasing her about everything from her weight to her acne to her outspokenness about civil rights. Many of them never left Port Arthur, so 10 years hadn’t brought many changes. But here was Janis, a rock star, a counterculture icon and a wealthy woman, returning with sweet revenge on her mind. And a secret hope that she might finally be accepted. She arrived in hippie style – a loose white blouse, purple and pink feathers in her hair, oversized tinted glasses, and a bounty of bracelets jangling on each wrist. But as often happens when we go home, we revert to our insecure, teenage selves. At the reunion, Janis quickly felt the chill of her classmates, who stood apart, snickering and making catty remarks about her.

“It was such a sad thing that even with the great success that she’d had they couldn’t applaud her,” her younger sister Laura Joplin tells Classic Rock. “The things she’d accomplished didn’t register, because it wasn’t their success. The best they could do was give her an old tyre as a trophy for coming the longest distance to the reunion. That was so insulting.”

The few fellow outcast pals Janis had from the class of 1960 didn’t bother to show up. So there she was, a thin-skinned rebel, being grilled by the local TV station. When asked: “How were you different from your schoolmates in high school?” the armour fell away, as Janis said: “I don’t know. Why don’t you ask them?” And when asked: “Did you go to the high-school prom?” she choked back a little sob and said: “No, I wasn’t asked.” But then, recovering her royal bearing, she turned it around with a chuckle and said: “And I still haven’t recovered. It’s enough to make you want to sing the blues!”

Joking aside, the blues that Janis sang, mined deeply from a sensitive soul, was firmly rooted in her stormy relationship with Port Arthur.

A little about the town without pity. Port Arthur was established in 1895 as a railroad stop. Six years later a gusher put it on the map as one of Texas’s new oil meccas. By January 19, 1943, when Janis Lyn Joplin was born, Texaco and Gulf Oil had set up refining industries there. Janis’s dad was an engineer for Texaco, her mom a registrar at a local business college. Janis later said: “It was a town filled with bowling alleys, rednecks and plumbers, leading such tacky lives.”

But Janis and her younger siblings Laura and Michael were encouraged in art and music and, in Laura’s words, “given permission to be different”. She says: “My dad would sit us down to listen to his favourite records. The one that comes to mind was a Pablo Casals concerto. Dad was trying to get us to feel the power of the emotion in the music. So we grew up believing that music was serious. When we did laundry, and my mom, who’d been a singer, had show tunes on, it was about learning how to sing. And she’d stop you as you were carrying the towels across the living room, and say: ‘Support those notes. Enunciate those words. Your audience needs to hear you!’”

By high school, Janis was painting, strumming folk songs on her guitar, reading Jack Kerouac, writing for the school paper, and wearing sweatshirts, tight jeans and loafers without socks. The classic free-spirited artist in the making. Along with that came a bright-eyed intelligence and independence.

“The world was changing,” Laura says, “and Janis’s interpretation of being good included things that a lot of people in the south weren’t yet ready to include. Port Arthur was conservative, and had an active chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. So when Janis was in high school, speaking out for racial integration during a social studies class discussion, she became a target.”

Loving Odetta and Bessie Smith, smoking weed and sneaking into seedy nightclubs in nearby towns on weekends with a bunch of male friends further sullied her reputation, setting her apart from her classmates. After a semester at Lamar College, then a year at University of Texas in Austin, where a bunch of cruel frat boys orchestrated a campaign to vote her Ugliest Man On Campus, Janis finally escaped Texas in 1963. Or as she once put it: “They laughed me out of class, out of town and out of the state.”

“She hitchhiked to California with her friend Chet Helms, and didn’t tell my parents,” Laura recalls. “She just took off. She was a pretty headstrong kid. But it was a period where she was kind of lost, and still searching.”

In her first run at San Francisco, Janis joined the local folk scene, singing in front of audiences in beatnik coffee houses like Coffee And Confusion. Regulars there included Marty Balin, David Crosby, and James Gurley who would be the lead guitarist with Big Brother & The Holding Company, a band that Janis would front. Janis lived for free in the basement of a house that belonged to a folk-singing couple. She’d go upstairs once a week, sing a song, and that served as rent. Her remarkable voice had that effect on almost everyone who heard her. When she wasn’t singing, she studied records by Lead Belly and Billie Holiday.

“They can go no farther than from A to B in a song and make you feel like they’ve told you the whole universe,” Janis would later say. On Sundays she went to black churches, sat in the back and sang gospel. Money was always tight, so she lived off early-morning raids on the produce district, grabbing crates of damaged fruit. When that didn’t work she shoplifted. She painted and wrote poetry. She even met her idol Bob Dylan at a club. “Bob, I just love you,” she said. “I’m gonna be famous some day.” To which Dylan replied: “Yeah, we’re all gonna be famous.”

There was also lots of booze. And drugs. As Chet Helms said, they “walked right into the speed crowd. And Janis felt she had to pay her dues to sing the blues, that in some sense, she had not suffered enough.” Long before acid became the hippie drug of Haight-Ashbury, everybody was doing Methedrine. It was regarded as a harmless antidote to depression, fatigue and weight problems. And for beatniks, meth was part of the artistic process. It was a way to make more paintings, more novels and more songs. The availability of the drugs, and Janis’s hunger for new experiences, made her particularly susceptible not only to Methedrine, but also the even more insidious heroin. Her hangouts changed to Amp Palace, a cafe where amphetamine junkies hung out, and the Anxious Asp, a lesbian bar. As she later said: “I wanted to smoke dope, lick dope, suck dope. Anything I could lay my hands on, I wanted to do it.”

It didn’t help that the guy she started shacking up with, Peter de Blanc, had an even worse addiction problem. “Her relationship with Peter was intense,” says her sister Lauren. “She had used, overused and gotten so strung out that her friends held a party and they passed a hat to get enough money to put her on a Greyhound bus and send her back home.”

In May 1965, an emaciated and exhausted Janis returned to Port Arthur. “She got out of a taxi with all of her clothes packed in various shoe boxes that kind of tumbled on the ground,” Laura recalls. “She was definitely small and skinny, I think down to about eighty-eight pounds. We were overjoyed to see her, though. I took her down to Jefferson City to get her new clothes, and pretty quickly she gained some weight back. I think she was finally committed to seeking help and getting her feet on the ground. It was the beginning of a very positive period in her life.”

Positive but daunting. The idea of Janis going straight and living up to expectations was like putting a wild songbird in a tiny cage. She re-enrolled at Lamar College to pursue a teaching degree, swore off booze and drugs, and firmly put musical dreams out of her head. She combed her wild hair into a matronly bun, wore conservative dresses. She even played canasta with friends. To complete the Stepford-esque picture, she got engaged to Peter de Blanc. While de Blanc returned to his home town in New York to get clean, Janis started making a marriage quilt, and shopping for china, linens and cutlery for the wedding. A future of white picket fences and PTA meetings beckoned.

In a letter Janis wrote to de Blanc that summer, she says: ‘I have your picture on my desk where I do my homework, and everyone in the family’s seen it at least three times. Everyone agrees you’re handsome. I really love you. In attempting to find a semblance of a pattern in my life, I find I’ve gone out with great vigor every time and gotten really fucked up. All I did was be wild, drink constantly, fuck people, sing. Jesus fucking Christ, I want to be happy so fucking bad.’

- When Jimi Hendrix Came To London: Jeff Beck, Ronnie Wood And More Look Back

- The Doors: the making of Morrison Hotel

- Janis Joplin film wins Venice premiere

- Janis: Little Girl Blue

“My sister was doing some soul searching,” Laura says. “She had not found her place. There was still a strong desire for music. She was seeing a therapist, and he tried to get her to see that music and drugs weren’t wedded, it was possible to do one without the other. That didn’t prove to be possible for Janis. But she was trying to figure it out.”

She started to hear from de Blanc less frequently. And one day when she called his number, a female voice answered. Janis discovered in short order that her fiancé was engaged to another woman, who had a child on the way. It crushed her.

Laura says: “I don’t think it was an intentional desire on his part to lie to her as much as it was to keep her in Port Arthur, safe and grounded. Janis was doing good, had been home for a while, but she was feeling bored. So after the engagement was broken she wanted a break between semesters at college. She went back to California, loved it and never came back.”

In late May 1966, Janis moved to San Francisco with a mission: to make it – and make it big. By then, Chet Helms had become a club owner and manager, and was working with a new band called Big Brother & The Holding Company. They were auditioning girl singers. Janis listened to two of their songs and told Chet: “That’s what I want to do!”

Two weeks later she made her debut with Big Brother at the Avalon Ballroom. Drummer Dave Getz, bassist/guitarist Peter Albin and guitarists Sam Andrew and James Gurley had been together for more than a year, and made a name for themselves with their raw, bluesy instrumentals. Andrew later said: “We were heavy. We’re in the newspapers all the time. We are doing this woman a favour to even let her come and sing with us. She came in and was dressed like a little Texan. She didn’t look like a hippie, she looked like my mother, who is also from Texas. She sang real well but it wasn’t like: ‘Oh, we’re bowled over.’ It was probably more like, our sound was really loud, it was probably bowling her over. We weren’t flattened by her and she wasn’t flattened by us. It was a pretty equal meeting. She was real intelligent and she always rose to the occasion. She sang the songs. But it wasn’t like this moment of revelation like you would like it to be, like in a movie.”

That said, it’s undeniable that in the months after, Janis’s singing and stage presence blossomed at a rate that the Big Brother boys couldn’t match. It was as if all the pent-up and repressed hurt and yearning from Port Arthur came bursting forth in one soulful eruption, informed and refined by her study of heroes such as Bessie Smith and Otis Redding. Interviewed at the time by Flip magazine, even Janis seemed surprised at her growth. “I don’t know what happened. I just exploded. I’d never sung like that before. I used to stand still and sing simple, but you can’t sing like that in front of a rock band. You have to sing loud and move wild with all that in back of you. Now, I don’t know how to perform any other way.”

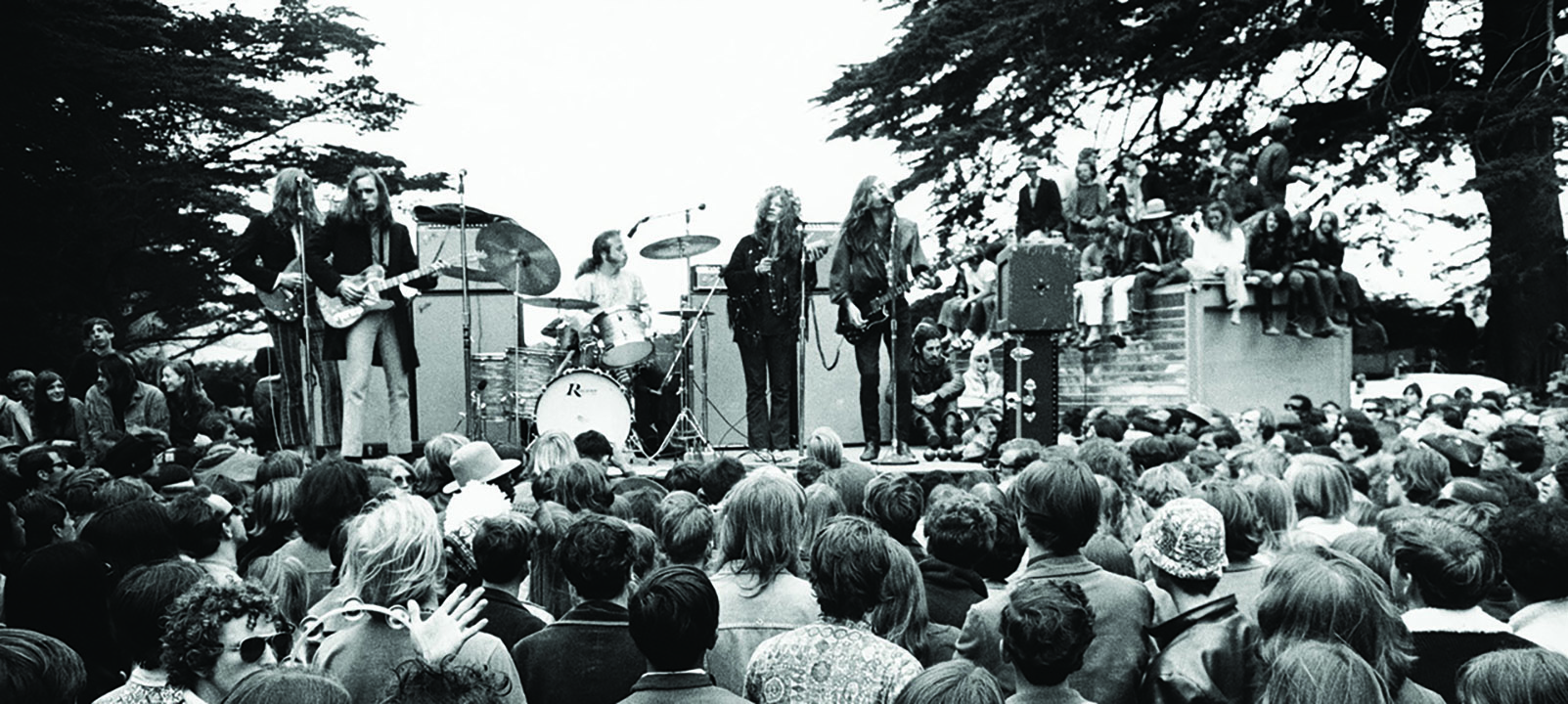

Bigger audiences and greater acclaim followed, giving Janis her first taste of stardom. And in the middle of her rise, her family came west to see what all the fuss was about. “We got to see Janis’s apartment,” Laura recalls, “near Golden Gate Park, and it was a hippie pad – mattresses on the floor, madras bed covers. Janis had just had a poster done, and it was a photo of her semi-topless, with beads and a shawl. She had papered the living room walls with these posters. When you walked in the door, that’s what you saw. Janis said: ‘Oh, it hardly shows, Mother, it hardly shows.’ She walked us through the neighborhood, past the boutiques, and introduced us to friends. Later that night she brought us to see Big Brother at the Avalon. And that was… surprising. It was hard to get. It was such a different sound than anything we’d ever heard.”

She adds with a laugh: “When we left the Avalon, I remember my mother saying to my dad: ‘You know, dear, I don’t think we’re going to have much influence any more.’”

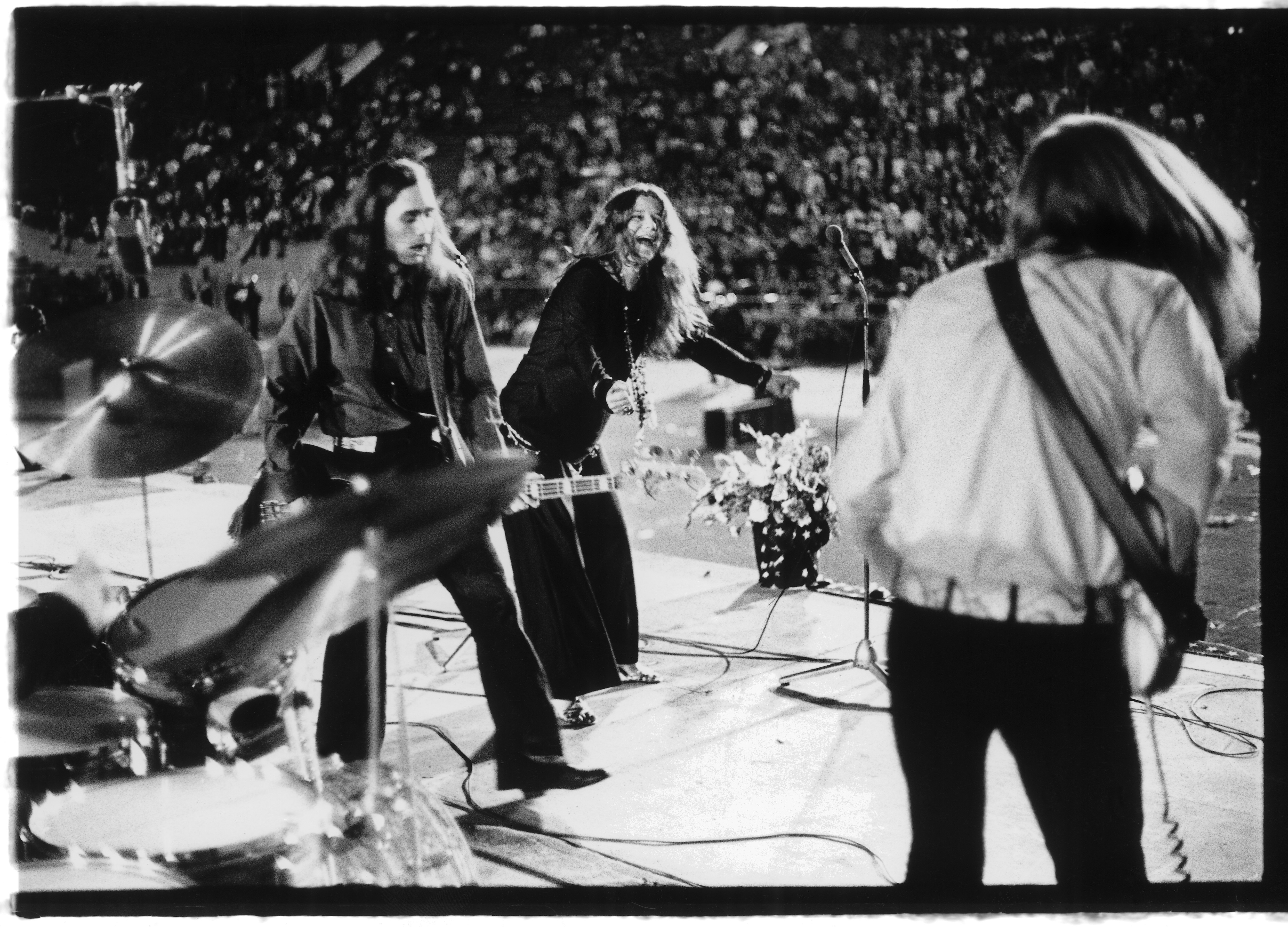

In June 1967, Big Brother appeared at the Monterey International Pop Music Festival in California. Drummer Dave Getz said: “In the beginning, she didn’t try to take over. She really tried to integrate into the band and be part of it. But the big turning point was Monterey Pop.”

You can draw a sharp before-and-after line to Janis’s career, even down to her show-stopping delivery of Big Mama Thornton’s Ball And Chain. In those eight minutes, the legend was born. Janis, in the throes of the slow, minor-key blues, eyes closed, microphone against her lips, wringing out ragged and multi-tone soul screams from her tiny frame, then hushing to a whisper. Swaying, pumping her fists, twirling her hips, shaking her thick matted hair, her pale face beaming in ecstasy. As a performance, it’s a combination of total command and vulnerability. And that’s what makes it so relatable, so powerful. It’s the difference between a great technical singer and someone revealing her innermost self.

“Once she got real recognition from the Monterey Pop Festival,” said Sam Andrew, “I think she began to see what the possibilities were. And the possibilities were somewhat over-the-top.”

After Monterey, Janis sent a bunch of positive reviews and a letter home that said, in part: ‘This band is my whole life now. I really am totally committed and I dig it. Wanted to send you these clippings. Since Monterey all this has come about. Did Port Arthur news have anything on these? If so, please send. I just may be a star someday. It’s funny, as it gets closer and becomes more probable, being a star is losing its meaning.’

Of course, the rest of the story is a fast-motion rise-and-fall montage: signing with Columbia records and manager Albert Grossman, Cheap Thrills, gold albums, world tours, TV appearances, Janis going solo, Woodstock, Pearl. And then, on October 4, 1970, a heroin overdose and death. She was 27. But was it an accidental fall?

“I don’t think Janis was living a life with the inevitability of death,” Laura says. “I think she was getting cleaner, and her life was getting stronger. But, who knows how, she ended up with some heroin that wasn’t normal. And just a little skin pop of that to relax ended up killing her. It was far from a typical overdose.

"Someone gave Janis the drug, then left. Janis walked down to the lobby, chatted with the desk clerk, got some change, bought some cigarettes, went back to her room, sat down on her bed and fell over dead, still clutching the change in her hand. The coroner got rid of the excess heroin after the police took it. When people asked to check it, it had already been destroyed. That’s the story I’ve heard. Authorities were frightened of drugs, and they wanted this to be a fear story.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #224.

Forty-five years on, Janis’s true legacy lives on not as a drug casualty, but through her music, and a superb new documentary, Janis: Little Girl Blue. When asked what she thinks her sister’s career might have been like had she lived, Laura pauses, and then says: “Really, what I think of is all the Thanksgiving dinners I’ve missed with her. I think she would’ve had a wonderful career, and still be singing. But there was so much living that never got done. She didn’t get to meet my daughter. We didn’t talk about the books that we’d read, and go shopping. That’s my sister.

“People remember things that fit in with the picture they have of the artist,” she continues. “There’s nothing wrong with that. But the legend is of a woman who had a tremendous ability to communicate emotionally and powerfully. And she also had a drug problem. Sometimes those things go together.”

Q&A with Amy Berg, director of the film Janis: Little Girl Blue

What was your initial vision for your film Janis: Little Girl Blue?

I read the letters [that Janis wrote] early on, and that was the angle that I wanted to take, to find a way to have Janis tell her own story. I had read [Janis biography] Buried Alive when I was a teenager, and I was influenced by her music, but I didn’t know who Janis the woman was. I think her legacy has always been tainted by the way she died, alone in this hotel room, rather than the way she lived and the things she left us with. I wanted to emphasise the woman, the artist and the musician.

How did your perception of Janis change through making the film?

She cared so much about everybody, and everybody liking her and everyone being happy, and she was just very generous with her heart. Some might say maybe she was too generous with her heart. But she definitely gave everything to everyone that she met. I went in thinking that she was less sensitive, I went in with some clichés in my head. Those were erased after I spoke to people and kept hearing over and over the same kind of thematic stories.

What moved you the most about Janis’s rise to fame?

She is a groundbreaking female who was not afraid to break the rules. She paved a path for women to walk on and be who they are inside. Janis gave them carte blanche to be who they are. There’s a freedom in that. It hadn’t existed before Janis.

Do you have a favourite moment in the film?

The letter that I open the film with is so important to me, because she’s trying to soothe herself in this letter. She’s taking stock of where she’s at. The line that really sticks out for me is: “Need to be proud of myself,” because obviously everyone was proud of Janis, and she knew that. She wasn’t naïve, but she still wasn’t able to comfort herself. That is so sad to me, because I think that she would have gotten there.

If Janis had lived, how do you think her career would have developed and what would she be doing today?

She probably would have mellowed out at this point, but I think her style would have been as original as it was back then.