Had she lived, Janis Joplin, the first great female rock'n'roller and a true icon, would have turned 80 on January 19, 2023. In 2004, the late Carol Clerk spoke to Joplin's family, friends and bandmates, and told the true story of her life.

It’s summer 1970, and Janis Joplin is on a roll, talking to her new friend Bonnie Bramlett.

“That’s the good thing about women, man… they sing their fuckin’ insides, man,” Janis races on. “Women, to be in the music business, give up more than you’d ever know… a home and friends, children and friends. You give up an old man and friends, you give up every constant in the world except music. That’s the only thing in the world you got, man. So for a woman to sing, she really needs to or wants to…"

Janis and Bonnie are sitting in the bar car of a train, sounding off about the female rock experience. The Festival Express has been carrying Janis, Delaney & Bonnie, The Grateful Dead, The New Riders Of The Purple Sage, Ten Years After and a host of assorted musos and freaks across Canada on a week-long trip that has them stopping off at Toronto, Winnipeg and Calgary to play a string of filmed open-air performances.

On the train, night and day have long since merged into an alcoholic blur filled with so many all-star jams and slurred, intimate confessions that the journey dubbed The Million Dollar Bash is becoming more of a legendary event than the actual concerts it serves. Janis is well into her stride, enjoying the attentions of Rolling Stone writer David Dalton and his tape recorder as she carries on bonding with Bramlett. “All my life I just wanted to be a beatnik – meet all the heavies, get stoned, get laid, have a good time… I knew I had a good voice and I could always get a couple of beers off of it.

“All of a sudden someone threw me in this rock’n’roll band. They threw these musicians at me, man, and the sound was coming from behind. The bass was charging me. And I decided, then and there, that that was it. I never wanted to do anything else. It was better than it had been with any man, you know. Maybe that’s the trouble.”

The train rattled on…

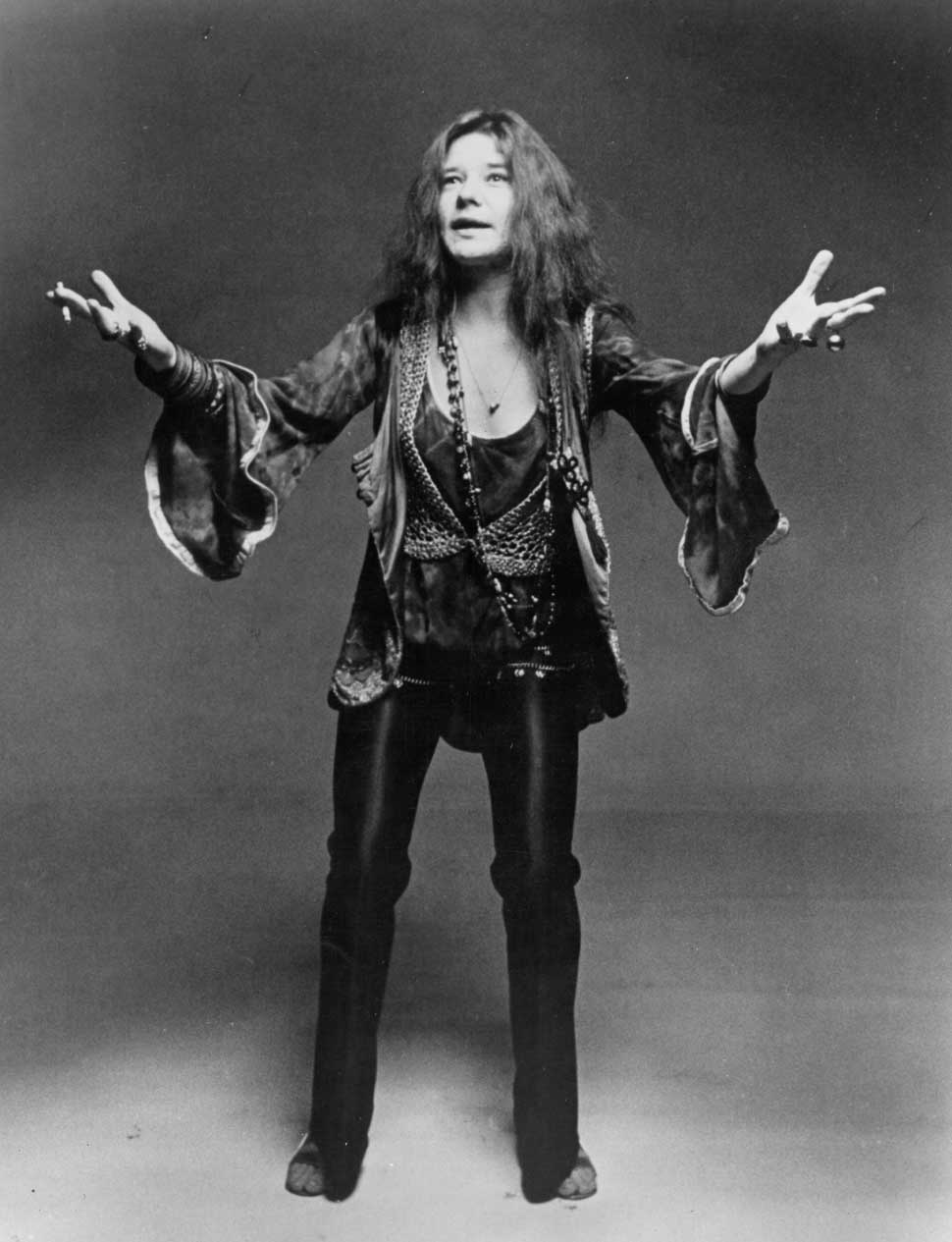

Those fragments of conversation, travelling down the years, bring back something of the pioneering spirit of Janis Joplin, the greatest white female rock singer ever.

On a good day – and there were many in her short career – Janis did indeed sound as though she had traded everything for the primal emotion she shared so powerfully with her audiences. What she gave was more than her singing, remarkable as that was. Steeped in blues, soul and American folk, Janis rode the electrifying surge of rock music and rose above and beyond it to stab the listener’s heart with great shards of passion that are shocking still in their intensity, their expression of the utterly personal.

By no means did she write the majority of her material, but it’s said she would never sing anything she couldn’t feel. In the words, in her sometimes lascivious delivery and in the wild, hair-lashing, hip-grinding, foot-stamping frenzy with which she performed her songs on stage, the element of lust and sex is undeniable, but at its root this was all about love – desired, unrequited, lost or simply unattainable.

“I’m selling my heart!” Janis cried once, theatrically. And in her music she usually sounded like that heart was breaking.

Some people have dismissed her as a melodramatist, a screamer. Well, she did scream. She wailed and shuddered and shrieked with devastating abandon as she urged those demons out. She was also capable of immense tenderness, the most humble resignation, a perfectly brazen defiance, a rip-roaring aggression and a sharp and witty resilience.

Janis’s sense of atmosphere and contrast, her phrasing, her range and abilities, were all extraordinary; she could sing two notes at once. She was, inimitably, a one-off – particularly since she immortalised her disappointments and failures in the guise of an opposite character dubbed Pearl.

This was the honky-tonk Janis, seen by some as an alter ego: the gaudy, street-smart, wise-cracking, hell-raising mama who dominated the stage – and indeed many areas of her private life – with a bottle of Southern Comfort, a swathe of fluorescent feather boas and a flash of gold sling-back shoes, the language of a docker and a predatory lick of the lips to whichever man, or woman, might provide that night’s entertainment.

Janis Joplin biographer Myra Freeman memorably described Pearl as a ‘hard-drinking-swearing-always-partying-fuck-anybody-get-it-on-get-it-off-stay-stoned-keep-on-rocking floozy’. But Freeman often worried: ‘Was she to be Pearl or would she be Janis?’

Looking for love but regularly settling for sex, which was often fine and good for its own sake, relishing the creativity and freedom of her career while envying the stability of others’ lives, glorying in the transforming qualities of drink and drugs as she looked to a future in which neither would be of paramount importance, Janis Joplin was not the outrageous Pearl or the plain, Texan girl who craved the acceptance of her Port Arthur home town any more than she was a lonely and miserable victim of love.

From time to time she was all of those things, but they represented the extremes of a full personality which was quick, perceptive, intelligent, well-read, accomplished in art, devoted to music and memorably alive with laughter.

Disembarking from the Festival Express, Janis lamented in typically vivid style: “Goddam! There were three hundred and sixty-five people on that train and I only got laid sixty-five times!”

But even as she said this, even as she had raved to Bonnie Bramlett about the sacrifices she was making for her music, Janis was only weeks away from deciding on her retreat and marriage. She had long mythologised the ‘picket fence’ and the reliable, nine-to-five husband who went with it. Now, although her prospective bridegroom, Seth Morgan, was far from the solid, suburban god of her fantasies, she was increasingly seeing a future away from music, if not retirement.

Her sister Laura Joplin tells Classic Rock: “There was a certain frustration in her about some aspects of her life. It was hard to have relationships when travelling that much, and she was having ideas of… trying to live a more balanced life in terms of the amount of time she toured. I don’t think she was trying to leave the music business.”

Sam Andrew, Janis’s friend and guitarist in Big Brother & The Holding Company and The Kozmic Blues Band, agrees. He says today: “I could see her going through a ‘retirement’ and it would turn out to be a temporary phase, too. The ‘picket fence’ doesn’t exist. It’s an illusion. People who want a safe harbour don’t realise they would have to lose themselves completely to obtain that safety.”

Only three months after her sisterly exchanges on the train with Bonnie Bramlett, working toward a complete withdrawal from drugs and quietly arranging for a less frantic lifestyle, Janis died from an accidental overdose of heroin.

Janis Lyn Joplin came into the world on January 19, 1943 in Port Arthur, Texas, the first child born to her parents Seth and Dorothy. After six years Janis gained a sister, Laura, and baby Michael arrived four years later to complete the family.

They enjoyed a remarkable childhood, with their mother Dorothy determined to help them develop their initiative, creativity and independence. She taught Janis to play the piano, encouraged her flair for painting, and ensured that all three children discovered the magic of books and music and imagination. Dorothy insisted that the only boundaries they need worry about were those of the family and of society; their personal limits were endless.

Their father Seth was a strong and philosophical figure, a deep thinker who urged the importance of curiosity, enquiry and knowledge, but at the same time revelled in the home-made games and toys he produced for the youngsters.

In return for the respect that both parents demanded from their children, they gave the same back. Janis, Laura and Michael grew up knowing that their ideas and opinions were valued. They were invited to choose their own mealtime menus, served from a homely kitchen rich with the aroma of Southern cooking.

Asked her favourite memories of Janis at home, Laura replies: “Oh, being girls, trying on clothes together, cooking, family dinner conversations, things like that. It’s that wonderful quality of being loved and accepted and having someone to share growing up with. Janis reading books to me when I was younger, having her read Alice In Wonderland. Just very special times.”

Michael was seven when Janis started coming and going from the family home, but he holds dear certain recollections of his sister in her late teens and early 20s: “Her playing the guitar, her painting… Those were the best memories,” he says. “Janis helping me learn to draw. She was a very good renderer, and I wanted to be as well. She helped me. And I still use the simple rules she gave to a ten-year-old.”

Dorothy Joplin, herself from tough, farming stock, would never have suggested to her daughters any possible subservience to men in later life, or any undue emphasis on appearance.

Raised to be resolutely herself, to chase her own rainbow and try to rise to its height, the teenage Janis found herself increasingly at odds with her sternly conservative neighbours.

With time, she became estranged from most of her classmates. Preoccupied with their personal attractiveness and modest, conventional ambitions, they were unlikely ever to care about such things as the racist and sexist inequalities that governed their surroundings. An indignant Janis, with her unruly, wavy hair and outbursts of acne, her burning sense of fair play and her creative inclinations, had developed a progressive world view informed by current affairs and literature, including such revelatory, Beat-generation books as Kerouac’s On The Road. She could not conform to the inflexibility, the segregation, the small-town ‘respectability’ of Port Arthur, and she reacted against it.

She also began to rebel against her parents in a series of escapades that greatly disturbed the family harmony. Careering across the state line into Louisiana with a gang of male friends to listen to music, shoot pool and drink alcohol, being suspended from school for ‘improper behaviour’, she quickly and undeservedly gained what was then primly called a ‘reputation’ on account of her free-spirited and ‘unladylike’ antics.

Now, she began to feel like an outcast, shunned and gossiped about by the goody-two-shoes’ of her own age.

It has been written into Joplin legend – with no little help from the lady herself – that her early life was one of soul-destroying isolation, which was the root of an unending despair, the source of her greatest anxieties and insecurities, the experience that later gave voice and authenticity to her sensational take on the blues.

Further, it is ventured that the real accomplishment of her career, in her own estimation, was to be able to crow: “I told you so!” to her birthplace, to the people who rejected her there, while privately and desperately hoping for their approval at last.

There are elements of truth here. Janis didn’t get to have her pick of the boys in high school; she did fight with her parents; and she certainly resented Port Arthur as much as she yearned for its respect.

But it wasn’t all bad back then. Michael Joplin sees it as a typical scenario: “She was a teenager – ergo, rebellious. It’s almost a rite of passage but, yes, there were some tough times by all because of the normal tensions in the house.”

“There was frustration and unhappiness, and she was upset about a lot of stuff, but I don’t remember a lot about it,” Laura adds. “She graduated high school at seventeen and I was eleven.

“I don’t think it’s right at all that she was isolated and lonely. She had a close group of friends and they all identified with being different to the dominant society. So in that sense they were alienated, but they were in a subculture so she was never alone and she had a lot of support for her own views and her sense of separation.”

Sam Andrew remembers: “Janis was proud of being a Texan. She was proud of her ancestors, pioneers who had scratched out a livelihood in that barren Texas soil… Janis was not so proud of Port Arthur. In fact none of us really mentioned where we’d come from. The subject was not often discussed. The whole idea was to leap into the future and leave the past behind.”

Janis took her first leap into the future at the age of 17 when she graduated from Thomas Jefferson High and enrolled in Lamar State College of Technology in Beaumont, Texas. There she moved into a dorm room, majored in art and widened her network of allies. Not only did she have the companionship of some trusted pals, but she also forged new friendships with students who, like her, were excited by the unconventional and open-minded lifestyle of the Beats. Drinking into the night, Janis and her group held endless intellectual debates, put the world to rights, and indulged their appetite for books, art and music – primarily folk and blues.

Despite all this, and the thrill of a trip to Houston, Janis quit college only a few months into her course. She had discovered a reasonably liberated environment, but she wanted something more. In autumn 1960 she went home, passed a clerical course at Port Arthur College, then decided it was time to spread her wings again.

This set the pattern for the next few, transitional years, with a series of dizzying expeditions into the wider world invariably ending with her return to the family.

Janis worked as a keypunch operator in Los Angeles and sang in the coffee houses of the Venice Beach beatnik community. She hitched to San Francisco, went back to Lamar College, waitressed in a bowling alley in Port Arthur, soaked up jazz in New Orleans. In 1962 she began a fine arts course at Austin’s University of Texas, where she joined a group of like-minded artists, writers, poets, cartoonists and musicians in a bunch of dingy, rented flats known collectively as The Ghetto.

This was a key period for Janis. Her personal outlook was supported by her peers and also by a growing voice from the outside world, with people starting to protest at racial and female oppression.

Her artistic endeavours began to take a back seat to music. Taking up the autoharp, she formed The Waller Creek Boys with friends Powell St John and Lanny Wiggins, playing folk and bluegrass on campus and at venues in the wider Austin area.

Threadgill’s was one such bar. Its proprietor, country singer Ken Threadgill, was the first person to recognise Janis’s star quality. He suggested she accompany herself on guitar; he stressed the emotional substance that is central to the best music; he triggered her sidestep into blues singing. She never forgot him.

Janis had made her recording debut before moving to Austin. A jingle sung to the tune of Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land, it was intended as an advertisement for a Texan bank. But TV and radio audiences unfortunately never got to hear the first efforts of a rock-legend-in-waiting; someone decided that the target market could live without her proclamations that ‘this bank belongs to you and me’.

At the University of Texas Janis worked on a wild and tough, protective image, swearing, drinking, smoking cigarettes, dealing grass and allegedly experimenting with peyote and Seconal. No longer just ‘one of the boys’, she became romantically and sexually involved with men and, sometimes, women. Outside her own, liberal circles, she was treated with caution, if not scorn.

She ended the year being nominated for an Ugliest Man On Campus contest. And although she didn’t win, the humiliation of cruelly having her name put forward left painful scars.

Janis was on the move again. In January 1963 she hitch-hiked to San Francisco with an Austin friend, Chet Helms, and stayed there for a year, inspired by its unusually integrated multicultural society, and passing round the hat in the North Beach coffee houses where she sang.

Entering into the creative local scene, she moved in the same circles as Sam Andrew, Peter Albin and James Gurley (her future bandmates in Big Brother & The Holding Company) and other musicians including Nick Gravenites, David Crosby and Jorma Kaukonen, the latter later of Jefferson Airplane.

Less happily, she was arrested for shoplifting, hurt her leg in a motorbike accident and was beaten up in a street fight. Moving east to New York ’s Greenwich village, she again supported herself as a keypunch operator, continued her artistic pursuits, and apparently sampled methedrine, a semi-hallucinogenic amphetamine.

Having returned to her parents’ home in August 1964, Janis soon pointed her yellow Morris Minor convertible back to San Francisco. There her methedrine habit spiralled out of control at the same rate as her drinking, and it’s possible that she dabbled in heroin. She dealt meth, too.

In 1965 Janis met a man she intended to marry. Rich, charming, well-dressed and intelligent, he was also a heavy-duty speed freak, who shot up meth with Janis and ended up in hospital suffering paranoia and delusions.

Janis herself was in a bad way. Thin, and convinced she was going to die, she made her way back to Port Arthur in May. She quit speed, stopped drinking excessively, underwent therapy and, for the first time, sought help from her parents rather than challenging their way of life with the usual explosive arguments. She toned down her ‘jive’ appearance and her language in an astonishing effort to fit in with the townsfolk. She got fit, read voraciously and enrolled at Lamar Tech yet again, hoping for a career in sociology. She looked forward to her wedding.

“Janis went out into the world, back to regroup, and out again, and back and then out again, ” Laura says. “Part of her interest in leaving was excitement about finding something bigger and better, and part of her coming back was the disappointment she found. She got involved with abusive drug use and was lucky and smart enough to say: ‘Wait a second. I can’t do this’, and came back home and got it together.

“She had an attraction to go forward to music and the arts and a bohemian lifestyle, and then there was the desire to pull back and reflect about what she really wanted to do. She wrote a song about it, Got To Find The Middle Road. That was really the challenge for her. She wasn’t someone who went for beige.”

Of all Janis’s many disappointments, the most crushing of them was her fiancé, who turned out to have a pregnant wife and no intention of going ahead with any wedding, despite having kept up his courtship in letters, phone calls and even a visit in which he formally asked Seth Joplin for his daughter’s hand in marriage.

Janis started gigging around Houston and Austin. Then, in May 1966, a year after she’d retreated to Port Arthur to recover and rethink her life, she went to Austin for a week.

While she was there, The 13th Floor Elevators – famed for their weird and frantic take on garage – asked her to be their singer. And her old friend Chet Helms, on the phone from California, invited her to join a band he was managing in San Francisco. Originally called Blue Yard Hill, they had recently changed their name to Big Brother & The Holding Company. Travis Rivers, a well-known figure in Texas’s folk scene, was also involved in the new, exciting music emerging in San Francisco, and he corroborated everything Helms was promising.

Janis was scared of tumbling back into the drugs scene, and her friends had similar misgivings. Despite this, she left Austin with Rivers without telling her family, much to their anger and anxiety.

She arrived in San Francisco on June 4. It had changed. Janis’s previous experience had centred on the beatniks and folk sounds of North Beach. But now the focus had moved to Haight-Ashbury, the cool, artistic types were known as ‘freaks’, and the music was fuelled by the arrival of LSD. Later packaged all-embracingly as ‘psychedelia’, it was determinedly experimental, a distorted amalgamation of everything from blues to pop, with instruments soloing and lyrics arising from the acid-fuelled visions of their authors. Everything about it, from the sounds to the artwork, arrived in vibrant splashes of colour.

Janis immediately started rehearsals with Big Brother: Sam Andrew (guitar), James Gurley (guitar), Peter Albin (bass) and Dave Getz (drums).

On June 10, performing with them for the first time, at the 1,000-capacity Avalon Ballroom, she experienced her moment of epiphany, feeling the almighty weight of the band behind her and responding with a voice she had never known, the tumultuous, surging voice that welled up from within instinctively understanding what Ken Threadgill had said all that time ago about emotion and release. It was the voice that thousands would come to treasure above all others.

Sam Andrew tells Classic Rock: “The power was incredible … everyone in the band astonished me, including myself sometimes.

“But improbable as it may seem to an outsider, no one thing in the San Francisco scene was much more astonishing than any other thing. Everything was new, different, strange, thought-provoking, revealing, intense and educational. Janis was just one more feature in that landscape.”

Asked how Janis’s position as the lone female in the band affected its dynamics, Andrew replies: “We were not loaded with testosterone, let’s put it that way. There was truly a sense in the band that everyone had something to say, and that we were all the same person. Actually, the band could have used a bit more leadership and a few more hard edges.”

Janis moved into a house in Lagunitas, a valley town, with the other band members, their partners, children and dogs.

Andrew cites James Gurley as one of the most inspiring players around: “truly off into new territories”. Janis was also impressed with Gurley, and despite her colleague’s certain lack of machismo she began an affair with him. According to Andrey, it rocked Gurley ’s marriage but not the band.

Writing newsy letters home to the Joplin family, Janis bubbled with the sights and sounds of her new life but was deceptively reassuring; she soon picked up the bottle again and gave in to the temptations of the prevailing drug culture, although not to acid.

Sam Andrew remembers: “Janis and I did heroin from the first. Well it seemed like from the first, anyway. I know we were doing speed and sometimes heroin when we lived at Lagunitas. We didn’t really do drugs together though. For each of us, heroin was an individual thing. I was always interested mainly in using drugs to create or to write something … What Janis liked about heroin was that it turned her mind off. She was a compulsive thinker, analyser and critic, and heroin enabled her to become soft, unfocused, intuitive and receiving. She didn’t like marijuana because ‘it makes me think’.”

Big Brother & The Holding Company were one of the most innovative bands on the scene, their loose blues rock dressed with a spirited, improvisational bravura, while Janis poured out torrents of anguish, all the time becoming that little more flamboyant in her beads and newly acquired hippy garb.

Regularly appearing at the Avalon and the Fillmore (leased by the legendary promoter Bill Graham), Big Brother rose rapidly to prominence on the West Coast and beyond.

After parting company with Chet Helms (later appointing a new manager, Julius Karpen) the band began a four-week residency in Chicago where they signed to Mainstream Records. They recorded their first album in Chicago and Los Angeles, thereafter returning to San Francisco where they appeared at rallies, ‘be-ins’ and parties in the big city parks with The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service and Sir Douglas Quintet.

According to Sam Andrew, Big Brother gave Janis “high energy, intelligence and the freedom to become herself… We were unprofessional enough, and wise enough, to stand back and let Janis be anything she could be. And she extended the same favour to us.

“She was very conscious from the beginning of exactly where she wanted to go, much more so than anyone else at that time. She stopped screaming so much after a while, but I knew she would do that. I knew all of her voices. She had about seven. She was always calculating, and she could be very cold as well as very hot, but I always knew these things…

“She was one of the funniest people I have ever known. She had that edgy intelligence and a vivid and colourful sense of humour… which seemed almost preternaturally healthy and sane to me.”

Janis had never been conventionally pretty. And although there was something truly mesmerising about her presence and personality, she was continually insulted by the male tendency, even within the counterculture and the circles of the famous, to fixate on beauty.

“I was never attracted to Janis in a sexual way,” Andrew says. “But she had a very appealing manner… she made me glad to be alive. Being cruel about someone’s appearance is stupid and blind. Janis wasn’t selling her looks. Not at all, ever. She was trying to look as good as she could, and I think she did a great job a lot of the time. Janis was the person that I most liked to be with. She was perceptive and affectionate and always interesting.”

In spring 1967 Janis found her own apartment in San Francisco, which she shared with costume designer Linda Gravenites (ex-wife of Nick), and enjoyed a brief but joyful romance with Country Joe, leader of Berkeley’s agit-rock band Country Joe & The Fish.

Then came the Summer Of Love, reverberating around the world. Suddenly, Haight-Ashbury, hippies, LSD, peace, love and flowers were front-page news across Europe and America, with even George Harrison turning up to walk the famous streets of San Francisco. High-street shops sold beads and bells, and teenagers started growing their hair and saying ‘man’.

In San Francisco, the scene had grown naturally to embrace a whole creative community. The underground magazines, cartoons, posters and fashions were an integral part of a lifestyle which smiled on freedom and tolerance and spiritual exploration.

The bands were offering a multisensory, multi-coloured experience, with spectacular light-shows (which were usually best appreciated on dope or acid), and their influence had spread to other cities and countries that had such visionaries as Hendrix, The Doors, The Beatles and The Who. Big Brother and their contemporaries were at the forefront of the new rock revolution.

As the commercialisation of the era began in earnest, Janis stayed a step ahead, now dressing in the glitzy, offbeat outfits that Linda Gravenites designed for her. She marked her liberation by abandoning her bra, and endorsed the principle of ‘free love’ by propositioning all and sundry.

Some people have dismissed this as disgraceful promiscuity on Janis’s part, or explained it as a symptom of her private insecurities that dated back to Port Arthur. Sam Andrew reasons: “I think Janis enjoyed her sexuality. I also think that sometimes sex frightened her, and that her reaction to this fear, as in Mae West’s case, was a bravado and a constant coming-on to anyone around her. Life is complicated. Two opposite things can be true. In fact Janis embodied contrariness in a lot of ways.”

Big Brother & The Holding Company made their breakthrough at the Monterey Pop festival in June 1967. So enormous was their impact on the audience, with incendiary performances of such enduring now-classics as Down On Me and the epic Ball And Chain, that the band were forced to play a second set to be filmed for DA Pennebaker’s documentary movie. Their first performance hadn’t been captured, due to a financial dispute between Julius Karpen and the promoters.

Within two months, Mainstream had released the Big Brother & The Holding Company album. But although it introduced Bye Bye Baby, with its rich melodic sweep, and Janis’s own Women Is Losers, the band felt the recordings had dated, and complained of a cash-in.

They went people shopping, and in November were taken on by Bob Dylan’s considerable manager, Albert Grossman. They acquired a road manager, John Cooke, who became a lifelong friend to Janis, and in February 1968 signed to Columbia Records.

Now that they had a proper, international organisation behind them, Big Brother – specifically Janis – were more widely noticed, and won euphoric reviews. Their trips to the East Coast, during which they opened the Fillmore East in New York, were sensationally received.

Before long they were being billed as Janis Joplin & Big Brother & The Holding Company, much to the disquiet of the other members, who had been proud of their previous, crucial democracy. Various attempts had been made to headhunt Janis right from her earliest days with Big Brother. Now she was coming under increasing pressure to ditch the band and front her own, more ‘professional’ outfit.

They carried on, uneasily, as they alternated gigs with recording sessions in New York and Hollywood for what would be the Columbia album Cheap Thrills – a censored version of the band’s preferred title Sex, Dope & Cheap Thrills.

Released in August 1968 in Robert Crumb’s memorable cartoon-strip sleeve, it sold more than a million copies in its first month, and remains a fine testament to the group that many feel Janis should never have left. Among its greatest moments, Piece Of My Heart is a fiery collusion between female strength and weakness, Ball And Chain takes rainy-day heartache to the outer limits of misery, and Summertime is a masterful interpretation of an old standard, adapted by Sam Andrew.

At gigs, Big Brother generated chaos. Fans stormed the stage, trying to grab a piece of Janis, while others froze, transfixed by her raw and raucous cries of desolation. There were TV appearances. And stories of Janis smashing Jim Morrison over the head with a bottle helped her growing notoriety.

All the while, however, industry insiders and journalists were polishing Janis’s star, turning her head, still urging her to take control of her own career and to drop the Big Brother family, who played with feeling and instinct, in favour of a team of anonymous, hand-picked, highly skilled musicians.

Setting aside her long-held principles of justice and loyalty, and perhaps revealing the steely ambition that Sam Andrew had noted from the first, Janis quit the group.

She admitted, retrospectively, that the decision “may well have been a mistake”. Sam Andrew believes it may have cost Janis her life: “Anyone who drinks the way she did and who has her appetites is at risk. In Big Brother… we were all equal enough that anyone who really got out of line would be censured implicitly by the rest. That censure, though unspoken, was nonetheless quite palpable.

“One of the reasons Janis left the band was to escape this being judged on a daily basis. She said: ‘Peter [Albin, a group member who didn’t take drugs] would probably fire me if he could’. And, you know, I often thought that myself.”

Toward the end of 1968 she bought a Porsche Cabriolet, one of the most famous vehicles in rock’n’roll history, hand-painted in bright, psychedelic swirls that incorporated images of Janis and Big Brother. Shortly afterwards, on December 1, she played her last formal gig with the band, in San Francisco. By all accounts, she never stopped loving them.

The new group eventually came to be known as The Kozmic Blues Band, with influences including soul and R&B. Janis persuaded Sam Andrew to join as a hired hand, and he took his place on lead guitar alongside Richard Kermode (keyboards), Roy Markowitz (drums), Terry Clements (tenor sax), Terry Hensley (trumpet) and Keith Cherry (bass), later replaced by Brad Campbell. They were afterward joined by sax player Snooky Flowers.

Theoretically this should have been a fantastic vehicle for Janis, but there were problems from the outset. The band rushed into live performance too quickly, various members came and went, and they weren’t particularly compatible as people. Terry was a health freak, while Snooky was anti-drugs.

At the same time, Janis’s heroin habit was escalating. She overdosed at least once during this period and, contrary to doctor’s orders, continued to swig endlessly from her bottle of Southern Comfort. At the same time, she was posting the usual, cheerful letters to her parents.

Playing across America in the early months of 1969, The Kozmic Blues Band garnered mixed reviews, some especially damning. Rolling Stone warned that Janis might be ‘the Judy Garland of rock’, while the San Francisco Chronicle urged her to return to Big Brother. Many listeners disapproved of the horns in the music.

Sam Andrew: “Janis didn’t really know how to be a band leader. That was the only problem. I wish I would have known what I know today. I would have whipped that band into shape in no time. As it was, I was demoralised and stoned too. I was an employee. I had no business being there. Big mistake. I wasn’t helping Janis and I certainly wasn’t helping myself… I think Janis sounded great with brass. She was just too stoned and too incompetent at that time to make the most of the opportunity. We did have some great nights, though, with The Kozmic Blues Band, nights where she sang the best she ever sang.”

Janis’s own highlights with The Kozmic Blues Band included a prestigious TV appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show on March 16.

Michael Joplin: “I remember all the neighbours coming over to watch the show. The Ed Sullivan Show was the top, top, top thing, and someone from the block was on! It was huge news.”

Janis’s first and only European dates, in April and May, included London’s Royal Albert Hall. The audiences – and the reviews – were ecstatic.

She and the band were disappointed, then, that back in the States they encountered the earlier hostility from many quarters. They carried on playing just the same, and began recording in Hollywood in June for what would be their only album, I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama!, while Janis herself made a string of TV appearances.

At the same time, she was severing her last link to the heady, idealistic days of Big Brother, having dismissed Sam Andrew from The Kozmic Blues Band.

“I was numb, then puzzled later,” Andrew recalls. “She said: ‘Aren’t you going to ask me why I’m firing you, man?’ And I said: ‘No. It doesn’t make any difference now.’ “We were at an end. We both knew it. That’s why I didn’t complain. The dominant feeling I had about leaving Janis was relief.”

To replace Andrew, Janis brought in guitarist John Till, and they enjoyed a series of successful appearances at major festivals, including Woodstock on August 16.

Released in October 1969, I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama! crashed into the US top five. Many of the songs on the album were the staples of Janis’s live set. And it was on stage that the songs came into their own: the exhortations of Try, the richly emphatic Maybe, the resigned but still optimistic Kozmic Blues, the search for One Good Man, the frenzied Work Me, Lord.

Gigging continued, with Janis accepting invitations to sing with Little Richard and Tina Turner.

But disaster struck on November 16 at a show in Tampa, Florida, when an altercation with the police led to Janis being charged with using vulgar and obscene language. She was later fined a paltry $200.

But the incident horrified her family back in Port Arthur. Her parents Seth and Dorothy, while unaware of her heroin habit, had never been impressed by Janis’s constant swearing, drunkenness and uninhibited sexuality.

Her sister Laura says: “My parents were members of their generation. They didn’t approve or understand the motives and the drive and the lifestyle that the people on Haight Ashbury were living… but it’s clear that the bond of the family was always there if you read Janis’s letters.”

By the end of ’69 Janis had bought a comfortable new home in the hills of Larkspur, Marin County, and persuaded her old flatmate Linda Gravenites to share it.

She had also disbanded The Kozmic Blues Band. They played their last date, uproariously, at New York’s Madison Square Garden on December 19.

At last she took a rest. At the beginning of 1970 Janis came off the road, saw doctors in an effort to kick heroin, and went to the Rio Carnival in Brazil. There she remained clean, and met David Niehaus, an ordinary guy who had been adventuring in Peru and the Amazon jungle.

The genuine love affair that began there ended not long after Niehaus travelled to California and found Janis back on drugs, juggling her old, hectic schedule and entertaining chaotically at her Larkspur home. Things didn’t improve when he walked in on Janis with her long-standing female lover and smack buddy Peggy Caserta. Eventually Niehaus left for Turkey. Invited to accompany him, Janis chose her career instead.

She was getting another group together. John Till and Brad Campbell remained from The Kozmic Blues Band. Janis then recruited pianist Richard Bell, organist Ken Pearson and drummer Clark Pierson. She had to get it right this time.

As personalities the six clicked immediately, and from this vital beginning, the Full Tilt Boogie band discovered a vigorous musical empathy.

Around now, Janis adopted a nickname: Pearl. She had perfected the swaggering, hard-bitten, rowdy, rock’n’rollin’, drinkin’, cussin’ image she first developed in Austin, and had taken it over the top in a flurry of feathers, jewellery and riotous behaviour as she traipsed around bars and dressing rooms in search of pretty young boys – the lip-smackin’ queen of the one-night stand.

This was the Janis that the public paid to see, and the more famous she became the more she had to play the role. Sometimes it came naturally as an existing part of her personality, but sometimes it was just for show.

‘Pearl’ is usually thought of, simply, as the ‘wild Janis’, the single side of a coin – an easy, dramatic device. However, it’s more likely that she adopted Pearl in an attempt to reclaim her real self: a person of broad qualities, talents and interests; Pearl was the ‘entertainer’.

Laura Joplin: “I think she was trying to shake off the assumptions that people were making about her… she was beginning to feel hemmed in.”

Others have ventured that Janis used Pearl’s aggressive pursuit of men to hide her significant interest in women.

Laura retorts: “There are a number of people who have tried to present Janis as a frustrated lesbian, unable to be totally out front, but for the most part they have not maintained it once they have really started looking at her life.”

Sam Andrew: “I think there is an element of truth in the fact that Janis hid her interest in women from all of us, but I just can’t be sure. I have to say that she was quite interested in men, and genuinely so. That I do know. Here again is a case where Janis contained seemingly opposite qualities.”

Linda Gravenites left the household, no longer prepared to tolerate Janis’s relapses into heroin.

But the key word was ‘booze’ when, in April, Janis teamed up with Kris Kristofferson and Bobby Neuwirth (then a mainstay of her entourage) for a three-week drinking spree, later dubbed The Great Tequila Boogie.

The escapade featured a fleeting romance between Janis and Kristofferson. More enduring than their relationship was her poignant, acoustic rendition of his classic Me And Bobby McGee, a No.1 single for Janis after her death.

Five days after The Great Tequila Boogie ended with an outrageous tattoo party, Full Tilt Boogie hit the road, beginning with a private show for the Hell’s Angels in San Rafael, California – co-headlining with Big Brother & The Holding Company. The dates, stretching from May through to August 1970, and including the Festival Express train trip across Canada, were exhilarating, triumphant, and they found Janis on excellent form.

She was trying out material that the band would shortly record for the Pearl album, another posthumous No.1; Get It While You Can, dispensing waves of heartfelt advice, became another guaranteed show-stopper.

Still, Janis wasn’t too big a star to remember who had helped her. On July 10 she travelled to Austin for a jubilee party honouring Ken Threadgill. She wasn’t too big a star, either, to dream of recognition from the people of Port Arthur, telling TV host Dick Cavett that she was attending her 10th annual high school reunion on August 15.

She cracked: “They laughed me out of class, out of town, and out of the state – so I’m going home.”

The high-school reunion has become an essential part of Joplin legend. Documentary footage captures Janis flouncing up to the venue with an entourage, the homecoming heroine, all boas and sunglasses. It covers the press conference in which she lightly insults her home town. And it zooms in closely as Janis finally confronts her childhood demons, visibly squashed when her interviewer asks why she felt ‘apart’ from her classmates, and she admits, eyes down, that she was not invited to the prom.

Yet although these few moments of film speak more of humiliation than of the appreciation she had hoped for, and although stories abound of Janis yet again upsetting her parents during the visit, Laura Joplin says the reunion wasn’t quite the catastrophe of folklore.

“I think that Janis got what she needed from it,” Laura remarks. “She resolved some of her questions of her place relative to high-school people and whether or not she needed to be applauded. It wasn’t the wonderful triumph she would have loved, some huge, red-carpet honour from her high school. The perspective just wasn’t at Port Arthur yet. As a mature person, we all have to get through needing approval from others to being able to live with our own self-approval. That was one of the steps in her life.”

Janis would surely chuckle to know now that her tribute has arrived at last, with an exhibition in Port Arthur.

Janis had given her last public performance at Harvard Stadium on August 12. Returning to California, again free of heroin, she caught up with a motorbikin’ man she’d met at the tattoo party. Seth Morgan, from a rich literary family, had his own income and enjoyed the rock’n’roll lifestyle as much as Janis did. Still, they enjoyed quiet nights at home, and agreed to marry and have children.

(Seth would later serve five years for armed robbery, publish an article denigrating their relationship, become a successful novelist, take up heroin and hedonism, and die with his then lover in a motorbike smash in 1990.)

In September 1970 Janis was in Los Angeles, recording the album Pearl with Full Tilt Boogie and producer Paul Rothchild. Everything was going wonderfully. Janis was happy, enthusiastic, and the band were pinning down some great music. Quality and variety underpinned a collection that stretched from the staccato minimalism of Move Over through the dramas of Cry Baby, a heart-stopping avowal of generosity in lost love, to the unaccompanied and flippant Mercedes Benz, written in a carefree moment by Janis and Bobby Neuwirth.

Janis had been serious in her efforts to stay away from smack, and at this stage the last influence she needed was that of Peggy Caserta, who was in Los Angeles at the same time. Janis didn’t want to be drunk or hungover in the studio, so she replaced the alcohol with a hit of heroin after work once in a while, intending to quit again when the album was finished.

On Saturday October 3, Full Tilt Boogie completed the backing track for a new Nick Gravenites song called Buried Alive In The Blues. Janis, who was supposed to record her vocal track the next day, left the studio at around 11pm, stopped off for a couple of drinks, and returned to the Landmark Hotel where she was staying. The only person who saw her alive after that was the hotel receptionist, who gave her change for the cigarette machine.

Janis was alone in her room at the Landmark. She had expected Seth Morgan to join her that day, but he was too busy playing strip pool with a couple of waitresses in Marin County to make the trip to LA. Peggy Caserta also, allegedly, let Janis down.

Seth couldn’t reach Janis on the Sunday, and called her long-time friend and road manager John Cooke before flying into Los Angeles. Paul Rothchild told Cooke that Janis hadn’t turned up at the studio.

Entering her room at the Landmark, Cooke found Janis on the floor, between the bed and the bedside table, having taken an accidental overdose of unusually pure heroin. She was just 27.

Her ashes were scattered along the coastline of Marin County, as she had requested in her will.

Janis’s greatest legacy, of course, is her body of work. But she was more than just a singer. She was the first great female rock’n’roller. She was a feminist trailblazer, the first white lady to prove that no matter how you looked or dressed, no matter what you drank or smoked or shot up, you could take your place right up there with the boys if you had the talent and the self-belief and the balls to do it. She was a radical who wasn’t afraid to support a cause or speak her mind at a time when women were, too often, seen and not heard. Sadly, she was also the living and dying proof that heroin is a dastardly bedfellow.

Cut down at the peak of her career and at the very time she was actively trying to change her lifestyle, she speaks to us still today.

Her sister Laura Joplin, who supervises Janis’s posthumous product with her brother Michael, says: “There’s certainly a lesson in her life for me. It’s important to be true to yourself, as she said many times, and at the same time – what she didn’t quite get as clearly – to realise that you have to live with the consequences of your behaviour. And she died from them.

“When I hear her name now, I think of the sound of her voice and the power of her art, and sometimes there’s a continued amazement on my part at the ways that she touched people.

“She really helped people feel their own inner power and the ability to stand up for themselves and to go after what’s important for them…

“Janis is in many ways a public figure, she’s not a person any more, and one of her jobs is to represent issues and ideas to people.

“There’s not really a ‘true’ Janis. I knew her as a young sister, and there’s no way that the public is going to see that person. Her friends, when she was famous and running around, are going to see a different person than I knew, too. Each person has a perspective, and the image and the emotional value for them is true. To me, that’s very important, whether or not it gels with what I know. It’s a wonderful gift that she had to give to people.”

Sam Andrew, who was the musical supervisor of the recent touring production Love, Janis and is currently playing with the re-formed Big Brother, says Janis gave him “energy and humour, compassion and non-compromise”.

Since her death there has been a tendency to portray Janis as a victim, a tragedy. But Sam Andrew insists: “These things have been grossly exaggerated and mythologised, because the public needs a sacrificial idol. This is very deep-seated in human nature. That’s not to say that Janis was not, in her way, a tragic figure. She had enormous appetites and she couldn’t control them with her conscious mind. Her self-image was of a person in total control… She constantly had to confront the fact that she was helpless before her volcanic urges.”

Laura adds: “Anyone who dies young is within the definition of tragedy. But I don’t think Janis lived as depressed or confused a life as people had a tendency to see. She was a much more joyful, humorous, entertaining, alert kind of person than is generally described. If you think of her death as an accident, it’s very different than thinking of it as an inevitable slide.”

Michael Joplin: “What comes to mind immediately is her laugh. She had a great laugh, and it was infectious, and she did it a lot. She loved to have a good time… Books and such always have the dark side of Janis. But what we all remember is her laugh."

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 63, in February 2004.