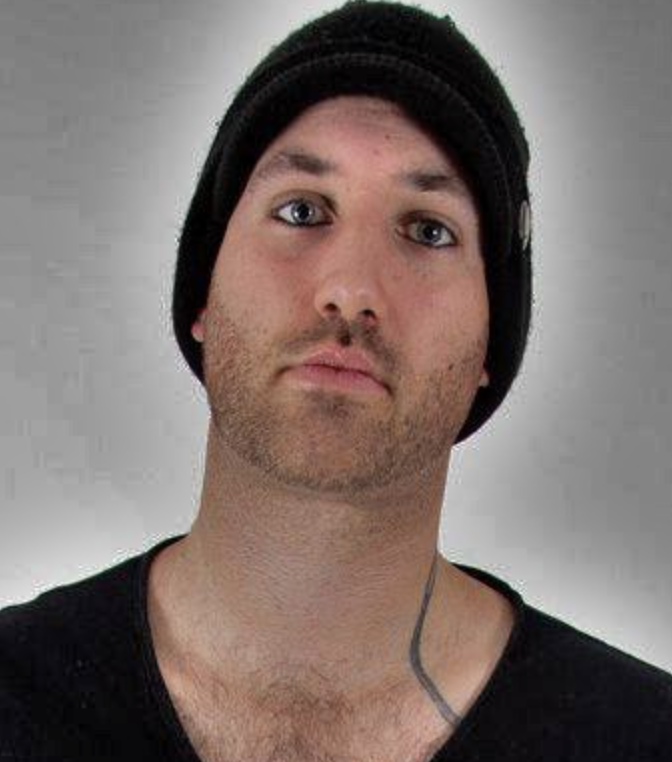

Jason Newsted on thrash metal, the Black Album and life after Metallica: “Playing Enter Sandman for the 1,000th time kinda wears on you”

Ex-Metallica bassist Jason Newsted looks back on the highs and lows of his epic career

Given he’s avoided the spotlight for the last decade, there’s an awful lot of love and respect in our scene for Jason Newsted. He was the young, bass-playing hopeful from Flotsam And Jetsam who found himself in the enviable yet daunting position of filling the shoes of Cliff Burton, Metallica’s legendary bassist who passed away in 1986.

With such a weight of responsibility upon him, it says much about Jason that he went on to become such an integral and beloved part of the Metallica family, helping to turn them into the biggest metal band of all time. Yet Jason’s boundless energy and commitment to the band took a physical toll, leading him to quit Metallica in 2001.

Since then he has led a nomadic existence, playing with everyone from Ozzy Osbourne to Voivod and fronting his own solo project, Newsted, as well as starting an art career that’s been remarkably successful. And he’s stepped away from the public glare to work at his own Chophouse studio with a revolving door of musicians. But whatever he does or chooses not to do in the future, Jason Newsted’s status as an icon is cemented. This, in his words, is how it all happened.

How do you look back on the first Flotsam And Jetsam album, 1986’s Doomsday For The Deceiver?

“Pridefully and respectfully. I just wish we’d have paid a little more attention to getting the intonation on them Flying Vs… haha! The fucking Arizona weather, you go outside and it’s 40 degrees hotter, and you’re going ‘Clunk-clonk.’ But we made our mark. We were setting ourselves up for speed metal, thrash metal, whatever you want to call it – all of our influences were the same.

That’s how it came from the desert. Anthrax, that’s how it came from New York; COC, that’s how it came from there [North Carolina]; Texas, Watchtower. For us it was Motörhead, Iron Maiden… those were the ones that made up our shit. So when you wake up and it’s 110 degrees in the morning, you might go a little faster, you get a little sweatier! You figure it out.”

How did you feel hearing the first mix of …And Justice For All, and how do you feel about the …And Justice For Jason remixes of the album people have been doing in the last few years?

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I love people’s enthusiasm, their determination, their love and their appreciation. If the Justice album had been mixed like a regular record, we wouldn’t be talking about it to this day. But because that isn’t the case – and I don’t necessarily think that’s that big a deal – we’re still talking about it all these years later.

I don’t even think they realised, in their drunken stupor, what they were doing, but they made the best garage band album ever. Black Keys, White Stripes, whatever power duo, garage rock stuff you wanna mention, James and Lars were the original garage rock duo, as far as that goes.

They always made the records that way, from [1983 demo cassette] No Life ’Til Leather, it was Lars and James, guitar and drums. On the original cassette, in Lars’ handwriting, in ink pen, on the label [it reads] ‘Turn bass down on stereo.’ On Life ’Til Leather! It’s just been that way their entire lives. They made Kill ’Em All that way, Ride… that way, Master Of Puppets that way… all those two guys in a room, over and over, and you’re gonna argue with the most successful of all time…?

Back then, I was fucking livid, are you kidding me? I was ready for throats, man. Because I thought I did a good job. But, up until it got to Metallica, I had only ever played one take on the bass. In Flotsam I wrote the song on bass and the guitar player covered the part I wrote. I never knew any other way, until I met Bob Rock, and then I could see how he made the bass its own thing. I didn’t know what the bass player did until about 15 years ago!”

Did you feel like you had an ally in Bob Rock when you were recording the Black Album?

“I don’t think I ever earned his respect like he had for James and Lars – because of what they had achieved, and they were writing the cheques – but I think he was firing on all cylinders. I wanted to get his respect, to show him I knew what I was doing.

I brought in a tenth of my bass collection, ‘Hey, let’s try this one or this one,’ sort of showing off a little, because you get told that this is the way to be a proper musician, where actually it’s the opposite. He knew that one bass was malleable and we could get every sound out of it. I started messing with multi-string; he supported me in the way of tough love. He already had five or six kids, and none of us had any kids at that point; he was just adding to his brood. We were just kids, man!”

Did any of you guys realise you were sitting on something special back then, when the record was being made?

“I’m going to go back to Sad But True, because that’s my highlight of the whole project, because of the weight. I struggled with Nothing Else Matters; I knew it made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up – it was undeniable – but I was kinda scared of it, to be honest, because I still wanted ‘CRUNCH!’ Sandman I thought was kinda corny, honestly.

The beautiful thing was that we all sat in the room together and played it out; 70 takes of Nothing Else Matters. After a while, you’re too close to it. ‘How much more delicate can I make it?’ It’s crazy I’ve just realised this: our softest song ever took down the biggest walls to allow our hardest songs ever to penetrate the world. When it was No. 1 in 35 countries in one week, and seven of those countries we hadn’t even been to yet? Dude, that doesn’t happen to a band who go ‘Die! Die!’ most of the time.”

Let’s talk about the Load period. How aware were you of the controversy surrounding you cutting your hair?

“People are so finickity. I very honestly never gave it one thought. I cut my hair in 1992, they didn’t do it till 1996. You know what else is really funny? We start getting to go to more and more countries, and as the borders get a little squirlier, those guys all still have their shaggy [hair].

My hair was nice, sometimes slick… like a cop! And I just cruise right though customs, and those fuckers are looking left and right, James is getting pulled – Lars would get pulled a lot. I walk on through and see my buddy and he’s got my spliff, and I’m like ‘click’ and away we go. So after a while they see this and, I dunno, I started dating models and Playboy girls, and they’re going, ‘What the fuck?!’ So you see the hair going back and back!”

You had the reputation as being the most metal one in the band at that time as well…

“My record collection was built in those years and it’s fucking beautiful, man. And one by one I would invite those musicians up to play with me. Once I built the Chophouse in 1992, it opened me up so much to so many musicians. I would have jam sessions with the guys in Machine Head and Exodus. Sometimes we’d jump away from metal and into other styles, to see if we could play those styles with the same as we used in metal. The Sepultura guys became really good friends and they would come down.

I was just still so hungry to learn about all different styles of music, people who invent their own instruments and sing in different languages, and if I pour as much of this good stuff in, then what’s it gonna pull out of me? I still have that to this day. It was important to me to keep the metal in Metallica.”

Tell us about the IR8 stuff with Devin Townsend. That’s where the problems with Metallica started, right?

“This was the very origins. I had just established the Chophouse in ’92, and by ’94 we had all the gear. Devin came down at the age of about 22 and was an absolute fucking maniac… dude, an hour-and-a-half of sleep a day for a whole week! And every time he would pick up a guitar you get, ‘Widdle widdle widdle,’ and you’re like, ‘Dude, where in the hell did that come from?! Now play it backwards!’

It was the first real project we took time to track in the Chophouse. It’s just drums and bass, Devin doing some mad guitar solo over the top, I go in and scream the vocal – done. Raw production, but an incredible accomplishment, because I always wanted my own studio. “The guys got wind of it and Lars said, ‘You gotta come up to the house.’

I didn’t really know what it was for, so I take my bass and go up there: ‘What’s up, guys?’ 'Dude, you know you’re in Metallica now, don’t you? You can’t just be making music and sending out tapes to whatever fucker with whichever fucker. You do understand that, right?’ 'Oh!' I didn’t realise at all! I didn’t know about the politics; I was just sharing some metal with my friends! I pretty much broke down on that day in front of Lars and James. I was like, ‘I’m sorry, it won’t happen again!’ And that was the first time.”

You admitted to us that you didn’t feel satisfied by being in Metallica at that time. Do you remember that quote?

“I’m proud of myself! That’s perfect! Absolutely, that is what is still real for me, and I think it was throughout the 90s. After the Black Album tour we had some money, but it was a totally different direction for me. I liked playing the songs and I could raise myself up for the people to play the songs for them. But Enter Sandman for the 1,000th time… it kinda wears on you.

I wanted to be that person who I knew myself to be on and offstage with Metallica. When they saw me, they knew they were getting everything, every fucking ounce of sweat left on that stage. The reason they were getting that, and the way I was able to do that, was because of the wacky music that I was playing offstage with my friends.”

Do you feel that Echobrain was overshadowed by you leaving Metallica around that time?

“Certainly, there was already a bunch of cards stacked against it because of that negativity. It was just the project that I had happened to take most seriously; it was never meant to be that I left a big band for that project. So it was a bummer that all of that was on them.

I wish I could have taken it further, but it was not the catalyst that sent me away from Metallica. The thing that set me away from Metallica is what I call ‘the perpetual dis’. No matter how hard I worked, there was still disrespect. Not the hazing that I got from the first six months of my career, but the general disrespect that I got, dismissiveness. The dis and dis, I call it.

It stemmed from, as a collective and as individuals, [the fact] they had never managed to deal with their grief from Cliff [Burton] when he died. This kind of shit, it manifests itself in young men’s minds, young millionaires’ minds. Spoilt, spoilt, spoilt millionaires’ minds, and I include myself in that… it would be hard to get your head around that. So it was much more a personal thing. I needed to rest; they refused to give me the time to rest; I had to leave to get that rest.”

Ozzy compared you to Geezer, when you played with him in 2003…

“Hard to fathom as well. I liked Red Bull a lot when I came in, so I was bouncing off the walls. I was 40 when I started playing with Ozzy, but he thought I was 26! His comment was, ‘You remind me of a young Geezer!’ and Black Sabbath had already recorded all of their albums by the time Geezer was 40! But, he was like, ‘Whoa! Who is that kid?’ I think that’s kinda why he said it. When I was trying to learn, he was one of the earliest influences on me. So, whenever I create bass parts, it’s always going to have a little bit of Geezer in it.”

Did you start getting into creating art when you first had your shoulder injury?

“Yeah, my first surgery was 2004, and I had to find some place to put my energy, and I only had one arm. It was quite a fucked-up period of my life, actually; I was highly addicted to the pain medicine. I had three shoulder surgeries and a knee surgery, and just kinda broke down.

The way that I played and lived my life finally took its toll on me. So I had quite a few tests and things over the years in my brain, and had little strokes and stuff. People don’t realise the physicality of it. I was trying to say to the guys in Metallica, ‘I need a minute, please, I need a minute, I’m on these pills…’ and they weren’t going to give me that minute. So I said very simply, ‘If you guys can’t give me that time then I need to stepaway.’ And the rest is history. Why would you keep giving yourself strokes?”

When was the last time you listened to a Metallica album that came out after you left the band?

“Never. I heard the one where they made the video in prison [St. Anger]. I heard one song with my dad while we were riding in the car in Michigan, because the radio is still pretty wed to Metallica, and it went on for fucking ever. It was eight minutes on the radio, and I went, ‘What the fuck are they doing?’ No disrespect, but I didn’t get it.

It was maybe harking back to the longer songs and the aggression and the tempo. And that stuff takes a lot of energy to play, and with James going up and down the fretboard like that, no one can touch it. I have a lot of respect for that thing, but I am quite a distance away from that type of music now.

I still like my heavy songs, but I sing for real now. I play the bass right up high, sing those backing vocals way up high. I still love Sepultura and stuff… but it really isn’t the way that I used to. I’d be happy to join them to do that stuff if they wanted me to. I still talk to Lars a fair bit, and I send him my stuff and he’s always super-supportive. I really appreciate it, and I respect his opinion. If he called me and asked if I wanted to throw down, I’d say yes, but I’m not sure if I’d say yes to anyone else.”

Published in Metal Hammer #361

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2021, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.